‘We’ll wear our Changpa [nomad] clothes, then take some goat hair and rub it all over ourselves,’ Skarma commented, ‘Then we’ll walk through the bazaar in Leh, and just you watch all the Kashmiris will come running after us and ask if we have pashmina to sell!’[1]

From the looms in Kashmir to haute couture boutiques the world over, the warm undercoat of pashmina goats is a highly valued luxury fibre. Herded by nomadic pastoralists in Changthang, sometimes at altitudes as high as 18,000 feet in icy cold winds, the trade in the fibre these goats yield is beset by controversy and intrigue. Setting the price involves much speculation and protracted debates and deals are often struck even before the fibre has been combed off the goat’s back.

Pashmina is recognised as a luxury fibre and commands some of the highest prices in the world of textiles because of its extreme softness, elegance and lustre. ‘Only vicuna from South America, musk ox and shahtoosh, none of which is available in anything approaching commercial quantities, achieve higher prices’ (Commonwealth Secretariat Report 1993: 14). The appeal of pashmina also lies in the romance and mystery surrounding its origin and its association with remote nomadic populations (Figure 1).

Fig. 1: Pashmina goats and tents in the Changthang. (Photograph by Tsering Wangchuk Fargo, 2016)

Pashmina is generally combed out of the goats in the month of June by male members of the family but women help out wherever necessary (Figure 2). The nomads say that during the winter, the pashm lies close to the goat’s skin, insulating it from the bitter cold; it is only when the winter is over that the pashm rises above the goat’s skin and can easily be combed out. In the past, combs made from wood or horn were used; today, they are mostly made of steel (Figure 3). A male goat usually yields up to 300 grams of pashmina, a female goat about 200 to 250 grams.[2] Good quality pashmina is determined by its long staple length and small diameter.[3] Pashmina from Ladakh’s Changthang, especially the eastern areas of Kharnak, Korzok and Rupshu is said to be of the finest quality because it has a staple length of two to three inches and a diameter of 12 to 14 microns. In comparison, the average staple length of pashmina in the rest of Ladakh is one to two inches and has an average diameter of 14 to 15 microns.

Fig. 2: Combing the pashm from goats. (Photograph by Monisha Ahmed, 2006)

Fig. 3: A selection of old combs made from wood and yak horn (left and centre). Also seen in the picture (right) is a modern-day steel comb. (Photograph by Monisha Ahmed, 2008)

Trade in Pashmina (1684–1959)

Pashmina has long been a major factor in economic and political struggle throughout the regions of Ladakh, Kashmir and western Tibet. While western Tibet was the main source for the supply of pashmina, Kashmir was home to a vast shawl producing industry. Ladakh, lying between these two regions, had a strict monopoly over the trade in pashmina. Though it was known that areas within Ladakh’s Changthang also bred pashmina goats, it was said that the finest wool came from Rudok and Ngari in western Tibet (Cunningham 1854: 214). In addition, traders from Ladakh were dismissive of pashmina from Ladakh’s Changthang saying the region was too close for its pashmina to be of superior quality.

Ladakh attained this monopoly in 1684 under the Treaty of Tingmosgang, concluded after the Tibeto-Ladakhi-Mughal War. Under this treaty, it was agreed that Tibetan authorities would undertake to supply all the wool and pashmina of western Tibet to Ladakh (Petech 1977: 77). At the same time, Ladakh, under a separate treaty with the Mughals, undertook to supply all this wool and pashmina to Kashmir (1977: 75). This practice appears to have been followed throughout the 17th and 18th centuries. Resentful of Ladakh’s monopoly, Maharaja Gulab Singh of Jammu declared war on Ladakh in 1834 (Figure 4). Under the leadership of his general Zorawar Singh, the region was successfully captured; he then set his eyes on western Tibet as he hoped to secure a monopoly over the entire shawl-wool trade (Lamb 1989: 357). However, Zorawar was defeated; and in 1842, a second treaty was signed—the Treaty of Leh, between Tibet, Ladakh and Jammu. This treaty reinstated Ladakh’s position as the mediary through which pashmina would pass from Tibet to Kashmir. This practice continued until the Chinese occupation of Tibet in 1959.

Fig. 4: Maharaja Gulab Singh and members of his royal family were quite fascinated by pashmina; miniature paintings often show him with an exquisite shawl draped around his shoulders. This piece is said to have been given as a tribute to Maharaja Ranjit Singh. The elaborately patterned shawl with a flamboyant design circling the body in a continuous oval, is said to be the creation of a French designer working with local Kashmiri artisans. Kashmir, mid-19th century; Hand-spun and hand-woven pashmina; 133 x 220 centimetres. (Photograph courtesy: Saffronart)

Prior to 1684, the first specific mention of the raw material seems to be a somewhat oblique reference by Francois Bernier, who visited Kashmir with the court of the emperor Aurangzeb in 1663 (Rizvi 2017: 37).[4] Earlier visual references at the monastic complex of Alchi allude to the use of shawls but the fibre they are made from is difficult to discern (Figure 5). The importance of this trade was first recognised by a Jesuit priest, Ippolito Desideri, who visited Kashmir and Ladakh in 1715 (Wessels 1924). By the time William Moorcroft and George Trebeck (1841) visited the region, the trade was firmly established; his accounts of it give us many details of the same (Rizvi 2017: 38–39).

Fig. 5: Paintings on the Avalokiteshwara statue at the Sumstek Temple in Alchi show a royal family sitting in their palace; both the queens are draped in what resemble shawls. (Photograph by Jaroslav Poncar)

The British too made several attempts to break this monopoly between Tibet, Ladakh and Kashmir. The first attempt, in 1820, was to send William Moorcroft, superintendent of the military stud farm of the Company near Patna, to Ladakh. Moorcroft went on the pretext of buying horses for the British but was actually there to investigate the possibility of diverting part of the pashmina to British India and establish a shawl industry there or in Great Britain itself (Rizvi 1999: 56). He achieved neither. In 1847, the British government sent Alexander Cunningham to locate trade routes used by smugglers, in the hope that the same routes could be accessed by the British (Cunningham 1854: 219). However, the Ladakhis maintained a well-guarded monopoly on pashmina produced in western Tibet and any attempt to export this article to areas other than Ladakh was severely punished by both Ladakhi and Tibetan authorities (Datta 1970: 18).

The trade in pashmina in Ladakh followed certain guidelines that were outlined in the Treaty of Tingmosgang. Only Ladakhi traders were allowed into the pashmina-producing areas of western Tibet to purchase the fibre, while their Kashmiri counterparts met them in Leh or Spituk (Petech 1977: 77). In Ladakh, most of this trade in pashmina from western Tibet was controlled by a group of traders known as palace traders (mkhar tshong-pa), who received certain privileges—such as, an exemption from tax and homes in Rudok—for their services to the royal family.[5] Their Kashmiri counterparts were known as Tibet Baqal.

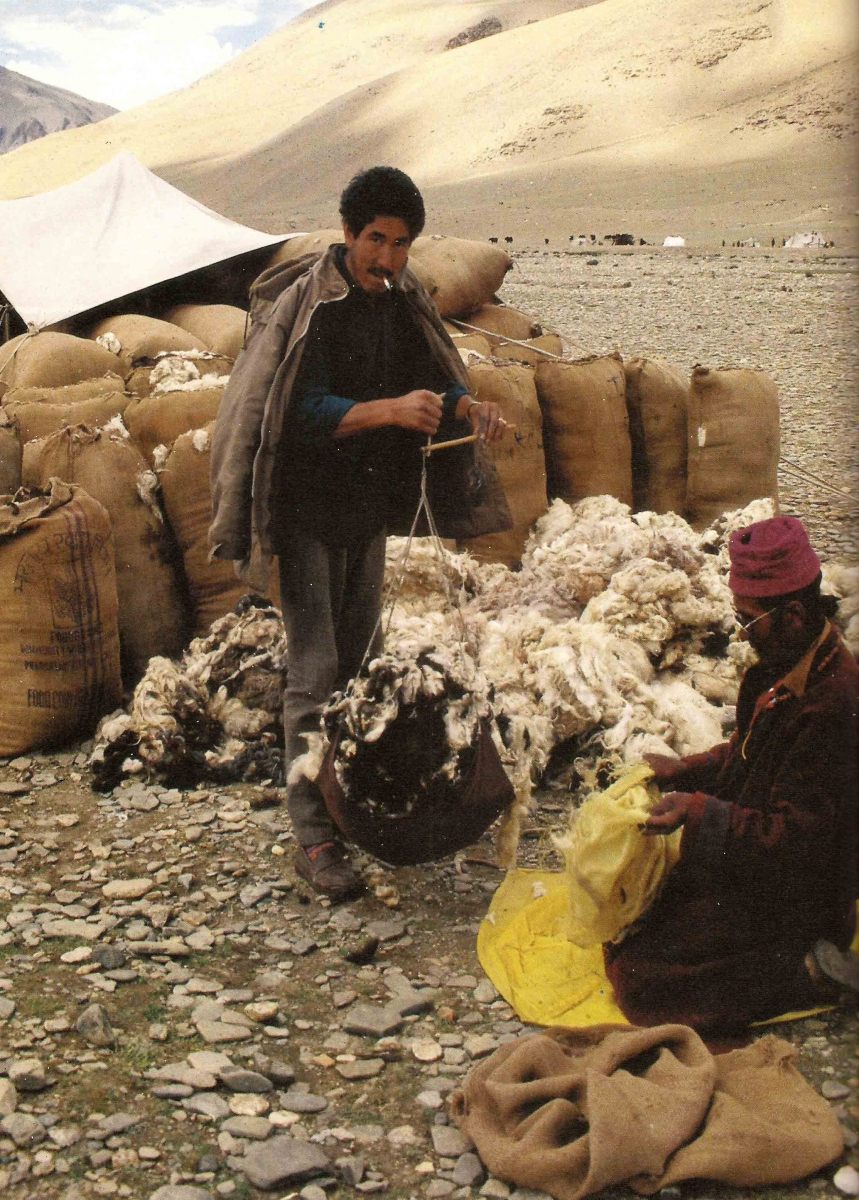

While most of the attention of these palace traders was focused on western Tibet, there was another group of smaller traders who purchased their pashmina from the eastern areas of Ladakh’s Changthang. These people were traders from Himachal Pradesh as well as farmers from villages in lower and central Ladakh (Figure 6). The quality of this pashmina was said to be inferior to that of western Tibet’s and, therefore, little interest was shown by palace traders in the fibre from these areas. Local traders to Changthang recall that just before the border between Ladakh and Tibet closed, in the late 1950s, a kilogram of pashmina cost Rs 2. However, at the same time, a kilogram of pashmina from western Tibet cost as much as Rs 15.

Fig. 6: Nawang Tsering, one of the last traders from Himachal Pradesh, weighing a nomad’s fibre using a scale known as nya-ga (a stick calibrated with 27 lines totalling 5 kg). (Photograph by Monisha Ahmed, 1993)

All trade along Tibet’s borders suffered heavily after the extension of Communist China’s rule over the country in 1950. However, it continued to operate, albeit under strain, until it came to a standstill in 1959, following the flight of the Dalai Lama to India and the total occupation of Tibet by China (Warikoo 1994: 861).

Patterns of contemporary trade

With the complete closure of the border between Ladakh and western Tibet, the Kashmir shawl industry had to turn elsewhere for its raw material. Quite naturally, they turned to the pashmina producing areas within Ladakh. One of the first effects of this increased demand for pashmina was a rise in its price. While the highest price for the sale of pashmina from western Tibet quoted for the period before 1962 was Rs 15 per kilogram, by 1970 the price of local pashmina had risen to Rs 300.

People involved in the trade of pashmina soon adjusted to their changed circumstances and the pattern of trade that followed continued to have some resemblance to that observed in the past. While some palace traders continued with the trade, new contenders also entered the market. Only Ladakhis, acting as middlemen, are allowed to directly purchase pashmina from these areas. Acting to some extent as their predecessors the Tibet Baqals had done, the Kashmiris come no further than Leh to pick up their supplies. With the entry of traders from Leh into Changthang, traders from Himachal Pradesh and farmers from lower and central Ladakh gradually lost out on the business as they could not afford the increase in prices.

Over the years, as a result of a growing demand for pashmina and spiralling prices, the government of Jammu and Kashmir has attempted to control the pashmina trade in many ways and break the nexus between the nomads, Ladakhi middlemen and Kashmiri traders. As early as in 1953, in an attempt to establish a monopoly of the fibre for Kashmir, similar to that set up 300 years earlier by the Treaty of Tingmosgang, they issued the Raw Pashmina Wool (Control) Order which gave them the right to prescribe the price of pashmina and forbid the export of pashmina outside the state without prior permission from the government (Rizvi 1999: 267). Later, they established the Sheep and Sheep Products Development Board (commonly known as the Wool Board) that stipulated the requirement of licenses to trade in pashmina (Ahmed 2017: 43). However, this system did not last long and over time the Wool Board became more or less obsolete.[6]

In 1995, the government set up the All Changthang Pashmina Growers Cooperative Marketing Society with the objective of eliminating middlemen and giving nomads a better price for their produce, as well as enabling them to sell directly to big companies in other parts of India. While the government was very enthusiastic about the cooperative, many of the Changpas approached it with scepticism. Since its establishment, the cooperative has gone through a period of uncertainty but currently (as of 2018) it seems to be working in a methodical and well-organised manner.[7]

In 2004, a pashmina de-hairing and processing plant was opened in Leh that is managed by the Changthang Pashmina Cooperative; the objective being to add value to the fibre in Ladakh. At the plant, the pashm is scoured and carded; it is not spun. The organisation’s aim is to promote the export of processed rather than raw fibre to Srinagar and elsewhere, as well as encourage the use of pashmina by local weavers and designers in Ladakh (Figures 7 and 8).

Fig. 7: Women from a local cooperative of nomad women pose in the sweaters they have knitted from pashmina. (Photograph by Monisha Ahmed, 2017)

Fig. 8: Pashmina jackets designed by Jigmat Couture, a husband and wife team that are graduates of the National Institute of Fashion Design, New Delhi. (Photograph by Wangail Lakrook, 2017)

Changing livestock preference

One of the direct outcomes of the growing economic importance of pashmina to nomads was a change in livestock composition and attitudes towards goats. In the past, sheep made up a larger portion of the herd, because wool was a guaranteed source of grain and pashmina had very little value. But today, transactions are no longer based on barter and grain has been replaced by rice and other items easily bought from government ration depots or the markets in Leh. The ratio of sheep to goats was three to one in the early 90s, but by 2000 it had reversed and there are now at least three goats for every sheep.

Along with this, the value accorded to goats has also increased. There was a time when yaks had the highest value among all livestock but with their decreasing number, they have been usurped by goats. In addition, the ritual value of goats has also changed (Figure 9). While sheep and yaks have always held a positive ritual value among nomads, this has not always been the case with goats. Goats were evidently regarded as inferior in the popular imagination of the place (Ahmed 2002: 52–53). For instance, goats frequently appeared in verbal insults and were a sacrificial animal (Prince Peter 1974: 309–310). Nowadays, newborn goats are especially cared for because they assure a future increase in the family’s supply of pashmina (Figure 10). Goats are also killed for meat with some trepidation. Thus, the ritual evaluation of livestock seems to correspond to their economic value and while the ritual value of sheep has not decreased, that of goats has most certainly increased.

Fig. 9: Goats being blessed by a monk. (Photograph by Monisha Ahmed, 2006)

Fig. 10: During migration, in 2006, a baby pashmina goat is secure in her saddlebag as she rides on the back of a yak. (Photograph by Monisha Ahmed, 2006)

Concluding remarks

The astronomical rise in pashmina prices since the 1960s has certainly benefited nomads, even as it has astounded the elders of Changthang who remember a time when wool fetched more than pashm. Often, they remain sceptical wondering how long the windfall will last. Certainly, the vagaries of nature do impinge on their prosperity; one bad winter and entire herds can be wiped out.[8] But the positive transformation in their lives far outweighs the adversities. Many nomads have become prosperous, annually increasing the number of goats in their herds for a higher pashmina yield.

Pashmina is one of the main economic assets that Ladakh possesses. It is the lucrativeness of the trade in pashmina that attracts local and international attention to Ladakh’s pashmina-growing areas. It is the trade in pashmina and its spiralling prices that continue to make life in Changthang worthwhile for nomads. As long as there is a demand for pashmina, their future in Changthang is secure.

Notes

[1] Personal communication, Skarma Rangdol, June 1994.

[2] These figures refer to the weight of the fibre before the coarse hairs are removed and it is cleaned.

[3] Fibre diameter is the single most important feature of pashmina; and the smaller the diameter, the finer the fibre (Ryder 1987: 5–7).

[4] The Hebers, a missionary couple working in Ladakh in the late nineteenth century, mention that when the Mughal Emperor Mirza Hedar (Akbar’s grandfather) came to Ladakh, the king presented him with some homespun pashmina and he admired it so much that he introduced its import into Kashmir (1978: 122). Hedar is also credited with having had the first two shawls woven out of pashmina.

[5] Eight families from Leh were appointed as palace traders; seven of these were Muslim and one Buddhist.

[6] By 1986, the ‘Raw Pashmina Wool (Control) Order; was suspended; licences were no longer required to trade in pashmina and free movement of pashmina was allowed.

[7] However, the nomads continue to sell a part of their pashmina to private traders and a part to the cooperative so that in the long run, they are able to maintain business relationships with both sets of buyers.

[8] The most recent snowstorm that decimated herds of pashmina goats in Changthang took place in 2013.

References

Ahmed, Monisha. 2002. Living Fabric: Weaving among the Nomads of Ladakh Himalaya. Bangkok: Orchid Press.

Ahmed, Monisha. 2017. 'The Contemporary Trade'. In Pashmina: The Kashmir shawl and Beyond, by Janet Rizvi with Monisha Ahmed, 42–45. Mumbai: Marg Publications.

Commonwealth Secretariat Report. 1993. Feasibility Study for the Establishment of a Small-Scale Pashmina Wool (Cashmere) Industry. London: Commonwealth Secretariat.

Cunningham, Alexander. 1854. Ladakh: Physical, Statistical, and Historical. London: W.H. Allen.

Datta, Chaman Lal. 1970. ‘Significance of Shawl-Wool Trade in Western Himalayan Politics’. Bengal Past and Present 89(1): 16–28.

Heber, A. Reeve and Katherine M. Heber. 1978 (1903). In Himalayan Tibet and Ladakh. New Delhi: Ess Ess Publications.

Lamb, Alistar. 1989. Tibet, China, and India. 1914–1950: A History of Imperial Diplomacy. Hertingfordbury: Roxford Books.

Moorcroft, William and George Trebeck. 1841. Travels in the Himalayan Provinces of Hindustan and the Punjab (1819–1825). Two volumes. London: John Murray.

Petech, Luciano. 1977. The Kingdom of Ladakh. Rome: Instituto Italiano Per iI Medio ed Estermo Oriente.

Peter, Prince of Greece and Denmark, H.R.H. 1974. ‘Zor: A Western Tibetan Ceremonial Goat Sacrifice’. Folk 16–17: 309–312.

Rizvi, Janet. 1999. Trans-Himalayan Caravans: Merchant Princes and Peasant Traders In Ladakh. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Ryder, M. L. 1987. Cashmere, Mohair and other Luxury Animal Fibres for the Breeder and Spinner. Southampton: White Rose II.

Warikoo, Kulbushan. 1992. ‘Ladakh’s Trade Relations with Tibet under the Dogras’, in Tibetan Studies: Proceedings of the 5th. Seminar of the International Association of Tibetan Studies, vol. 2: 853–861.

Wessels, C. 1924. Early Jesuit Travellers in Central Asia 1603–1721. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.