‘We are warp and weft,’ Abi Yangzom told me one sunny morning as she sat working on her backstrap loom, legs stretched out in front of her, body taut in spite of her age. Rhythmically working on the pattern on the loom, she went on, ‘the warp is the mother and the weft she inserts to make her cloth, is like the child conceived within her womb. As the cloth is made, so the child inside her grows. The finished fabric represents the birth of a child.’ (Figure 1)

Fig. 1: Abi Yangzom on her backstrap loom; her granddaughter Rinchen looks on. Rupshu, Changthang, 1992. (Photograph by Monisha Ahmed)

Among the nomads of Ladakh, life and the act of weaving are intrinsically linked. Here, the very origins of human existence, as well as the act of giving birth are tied to the making of textiles.[i] In the male loom, the weaving process and finished fabric signify the birth of a child. Here the warp, which is strong and tightly twisted, represents the man. The weft, which is weak and loose in comparison, is the woman. Together, they support each other and work towards a common goal: the birth of a child. At the same time, the male warp signifies one’s lineage and talks of connections between a father and his children.

The woven cloth is seen as an expression of a family network—a medium that links men to women and mothers to their children. Beyond the loom, the woven cloth also signifies links to one’s immediate family and affiliations to wider kin, rank and status. This essay will explore these notions, looking briefly at the history of fibres and textiles in Ladakh, and more specifically, their use and transformation over time among the nomadic communities. It will discuss traditional weaving systems of the nomads and their symbolic representations and interpretations in nomadic life.

The Changthang

Ladakh is India’s high-altitude border region, situated in the high reaches of the Himalayan and Karakoram ranges. Before being annexed by the rulers of Jammu and becoming a part of the Dogra kingdom in 1834, from the 10th century on it was an independent kingdom ruled by the Namgyal dynasty whose descendants came from Tibet. It is now a part of the north Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir.

Nomads inhabit the Changthang (byang-thang, ‘northern plateau’), the high-altitude plateau in eastern Ladakh.[ii] The Changpa (‘northerner’ as they are generically referred to) are predominantly pastoralists, keeping herds of yak, sheep (lug) and pashmina goats (rama) (Figure 2), along with a few horses and donkeys for transportation and as pack animals (Figure 3). In addition, those who live lower down in altitude also practise agriculture, tending some of the world’s highest fields. The estimated population is around 9,000 individuals (LAHDC-Leh 2001) with about 14 recognised groups.[iii] They are followers of the Tibetan School of Mahayana Buddhism with most belonging to the Drukpa (Red Hat) sect.

Fig. 2: The nomads herd their livestock of sheep and pashmina goats on the vast plains of the Changthang. (Photograph by Tsering Wangchuk Fargo)

Fig. 3: Nomads migrating to a new campsite. The yak in front carrying heavier belongings including the tent; they are followed by horses. (Photograph by Monisha Ahmed)

The textile tradition in Ladakh

Ladakh has a highly diverse textile tradition that reflects its physical, socio-economic and cultural environment. The range of fabrics used extends from elaborately patterned prestige garments made from trade textiles such as silk-brocades, ikats and velvet to simple homespun materials produced from locally available resources of wool and pashmina.

It is believed in Ladakh that weaving and the loom are modelled on the mythical loom of Duguma, the wife of King Gesar.[iv] Oral versions of the Gesar saga, which are recited throughout Ladakh, claim that she weaves one row a year and that when she completes the fabric on her loom the world will come to an end (Ahmed 2002:14). However, no one is able to say for certain what kind of loom she works on. There were some who thought it might be a backstrap loom since women in Ladakh, especially among the nomads, weave on such looms (Figure 1); this is unlike the non-nomadic, settled population where the weavers are men who weave on foot looms (Figure 4).

Fig. 4: A man weaving on a foot loom in a village in Ladakh. (Photograph by Monisha Ahmed)

Little is known about the historical development of weaving in Ladakh, and few, if any, early sources and records exist on this subject. Efforts to date the origin of the loom, weaving, and textiles are difficult as archaeological excavations have yielded little information. Clay spindle whorls have been found at Neolithic sites on the Tibetan plateau suggesting that weaving of some sort probably existed during that time (Myers 1984:21).

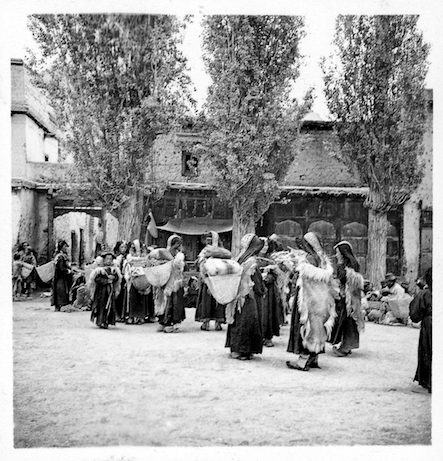

Ladakhis believe that the tradition of weaving is an ancient craft. They talk of a time before the weaving of cloth when their ancestors wore clothes made from animal skins, straw and the bark of trees. Later, they learnt how to spin and weave their own clothes. Animal skins are still used in Ladakh to make clothes and most probably this dates back to their earlier traditions. Hats (ti-bi) worn by both men and women are lined with goatskin (Figure 5). In Leh and areas of lower or western Ladakh, women wear goatskin (slog-pa) on their back (Figure 6).[v] In winter, among nomads, women wear felt capes (yo-sgar) lined with skin from lamb or kid, while men wear a robe (shan-lag) made from several sheepskins stitched together with the fur side turned to the body for warmth. They also use skin at night to cover themselves while sleeping.

Fig. 5: Wearing a hat made from silk brocade and lined with goatskin, the nomad is dressed for the annual horse race. (Photograph by Monisha Ahmed)

Fig. 6: A 1930s’ view of women gathered in Leh bazaar, wearing capes made from goatskin (slog-pa). (Photograph by Rupert Wilmot; courtesy R Wilmot, R Bates and N Harman, Lost World of Ladakh: Early Photographic Journeys in Indian Himalayas, Stawa Publications 2015)

Among the various sources available on the history of textiles in Ladakh, visual ones are of prime importance. Some of the most visible markers of this are the deep-relief rock engravings in Dras, Mulbekh and the Suru Valley. These date to the 8th century when the warrior king Lalitaditya Muktapida exerted his power on the Kashmir Valley and beyond (Petech 1977:14). These engravings are largely of Buddhist deities and their devotees; most of them are clad in the costume of Indian ascetics—usually a dhoti, an unlikely garment to have been worn in Ladakh. However, at the feet of the Avalokiteshvara image at Mulbekh, while female devotees are seen wearing half-saris, male devotees are wearing long robes with sashes typical to those worn in Ladakh today; there is also an image of a man wearing a hat similar to the ti-bi (Figure 7). In Dras, there is the figure of a horseman wearing a long-sleeved, short jacket over trousers and boots, holding a sword in his right hand. This is more likely the outfit of a Central Asian soldier and probably not a replication of garments worn in Ladakh at that time.[vi]

Fig. 7: Male figure wearing a robe and hat resembling those worn by men in Ladakh today. This deep-relief carving is found on the left of the feet of the Avalokiteshvara image at Mulbekh Monastery, 8th century. (Photograph by Monisha Ahmed)

A more valuable source of information on the history of textiles in Ladakh are wall paintings. In a cave above the village of Saspol are paintings of rows of figures of 85 mahasiddhas, each engaged in different activities. In the uppermost register, there is the Mahasiddha Tantipa, ‘The Weaver’, working on a foot-loom very similar in appearance to that used by male weavers in Ladakh (Figure 8; see Figure 4). He has a shuttle in his right hand and appears to be weaving white woollen fabric, locally known as nambu (snam-bu) and widely used for making clothes worn in the region. Scholars are not sure about who painted the cave and when, but some think they may have been inhabited by artisans who were working at the monastery of Alchi, across the river from Saspol, in the 12th and 13th centuries, as there are stylistic similarities (Khosla 1984:76).[vii]

Fig. 8: Mahasiddha Tantipa, ‘The Weaver’, weaving on a foot loom. Detail from a painting at Saspol Cave, estimated to be around 12th–14th century. Photograph by Monisha Ahmed.

At the Alchi Monastery, the wall paintings document the flourishing trade history of Indian and central Asian textiles, as they demonstrate a variety of techniques, motifs and styles rooted in central Asia, India, Iran and the Near East (Figure 9). At the three-storey Sumstek Temple, men and women wrapped in woollen shawls, clearly a product of Kashmir, are evident along with men wearing cotton turbans and long robes adorned with chequered ornamentation or Sasanian roundels (Ahmed 2005: 70). The Central Asian influence is also evident in the long kaftans, trousers and short boots (Goepper 1996: 266). The ceiling of the Sumstek consists of 48 panels that reproduce textiles of various techniques of manufacture, some of which were produced in Ladakh and others that came in through trade—such as brocade, lampas, and embroidered fabrics.[viii] Textile patterns which cover the ceilings are also shown on garments worn by the deities, the aristocracy and donors as portrayed in the murals; they provide confirmation that these reproductions of textiles are not figments of the painters’ imagination, but were in actual use at the time when Alchi was being built and decorated; or at least they had been seen by the artists in the 11th century and later.

Fig. 9: Detail from the painted dhoti of the Avalokiteshwara statue at Alchi Sumstek. On the upper floors of the palace sit the royal couple: the woman is wearing a shawl, the man a robe with Sassanian roundels. To the left of the man is a parasol with a hanging patterned with tie-dye circles, below that is a musician wearing a similarly patterned robe. The design is locally known as thigma and continues to be made in Ladakh today. (Photograph by Jaroslav Poncar)

Written records and information concerning this subject emerges with the arrival of missionaries, explorers and British officers who journeyed to Ladakh from the 17th century onwards. The earliest reference to Ladakhi woollen cloth is made in 1631 by the Portuguese priest Franscisco de Azevedo, one of the first European travellers to Ladakh, when he had an audience with King Senge Namgyal (Wessels 1924: 110).

Some of the earliest references to weaving and textiles among nomads are given by Moorcroft and Trebeck: ‘The tents of the Champas [Changpas] are of ragged black blanket, about four feet high, and open along the top. Their interior is furnished usually with abundance of dirty sheep and goat skins, some sewed into coats…’ (1841:47–48).[ix]

And British officer Alexander Cunningham provides the first detailed description of male and female apparel:

The men usually wear woollen great coats reaching below the knee. They wear leggings also, generally of thick coloured woollen …Their short boots are made of goatskin or sheepskin, with the hair or wool turned inwards …The cap is generally a piece of goatskin with the hair turned inwards, or else a woollen one edged with skin or coarse red silk …[the women] frequently wear long great coats and leggings like the men; but I have also seen them dressed in three or four thick woollen petticoats, and a sheepskin jacket with the wool turned inwards over the coat …(1848: 224).

Subsequent visitors to the region wrote about the textiles worn and used, while others contributed to the visual archive of craft and textiles of Ladakh (Figure 10).

Fig. 10: ‘Changpa women at the loom’, Walter Bosshard, 1927. Bosshard was a member of an expedition to Chinese Turkistan that travelled through Ladakh in 1927. (Photograph from Durch Tibet und Turkestan: Reisen im unberuührten Asien by Walter Bosshard, 1930. Stuttgart: Verlag von Strecker und Shröder)

Weaving practices

Throughout Ladakh, the loom is commonly referred to as thags-cha and the weaver as thags-mkhan. While weaving is widely practised throughout the region, differences exist. In the villages of central and western Ladakh, weaving is exclusively men’s work and is done using a foot loom that is portable and can be dismantled and reassembled within minutes (Figure 4). The craft is generally passed down from father to son but there are no strict rules proscribing this. Women are prohibited from weaving though they are involved in the preparation of the fibre. Male weavers allege that if a woman was to weave, her hands would burst into flames or the mountains would collapse. It is also said that if a woman touches a man’s loom she would become infertile; or if she comes into contact with her husband’s loom, there would be terrible fights between them often leading to divorce. Similar to weaving, dyeing and tailoring were traditionally predominantly male occupations.

In contrast, among nomads, both men and women weave. Women weave using a backstrap loom (sked-’thags), men a fixed-heddle loom known as sa-’thags (Figure 11; see Figure 1). The looms are portable and are made from wood, rope, wool and metal. Looms are usually inherited and one loom can last a few generations.

Fig. 11: A nomad weaves on a fixed-heddle loom. (Photograph by Monisha Ahmed)

Nomads weave with the fibre from their herds—sheep and yak wool (bal and kulu respectively), goat and yak hair (ral and sitpa) whilse pashm (le-na) from goats is always traded.[x] The Changpa say they find pashm difficult to weave with, as the fibre tends to break easily when stretched.

Along with a difference in looms, men and women have a fixed repertoire of items they make and fibres they work with. Women weave only with wool, making coverings for saddles, floors, tent walls and blankets, containers for foodstuffs and personal belongings, as well as the fabric used to make all clothes (Figure 12). In contrast, men work with hair— weaving tents, blankets and saddlebags in various sizes (Figure 13). While women dye the woven cloth, men cut and stitch it.

Fig. 12: A woman trims the pile of a floor covering – the ground is woven from yak and sheep wool, with the designs in acrylic yarn. (Photograph by Monisha Ahmed)

Subduing the demons

While it is mandatory that all women, including nuns, weave; it is not essential for a man to weave and monks are not permitted to weave. From a very young age, girls start helping their mothers clean and spin wool, and by the age of 13 they begin learning to weave. In contrast, men learn at a much later age, generally around 20 or even as late as 30. While most men stop weaving as they age and their agility decreases, women continue for as long as they are able to.

There are several reasons that relate why there is a much stronger emphasis on women’s weaving among nomads as compared to men’s. There is a local narrative that talks about this; it also relates the origin of the craft of weaving:

In the beginning the world was populated by gigantic demons. These demons were very strong and powerful; they destroyed everything in sight and even ate their own children. Some even say that the female demons (bdud-mo) ate the male demons. One day a big Lama came and told these demons that they must stop their bad ways and live peacefully with all living creatures.[xi] The Lama then taught religion to them. The male demons, who were wiser, listened to the Lama and became men. But the female demons did not. They still went around creating havoc. So the Lama taught the female demons how to weave. Then they became women. But in order to stop them from becoming demons again and going back to their wicked ways, they had to keep weaving. That is why, even today, women are kept busy weaving the whole day so that they do not stray back to their bad ways.

Despite her age, failing eyesight and arthritis, Abi Yangzom faithfully unrolls her loom each morning, emphasising the importance of a woman’s weaving: ‘There is always the danger that women who don’t weave will become the demon again; that is why we women must keep weaving.’ Women realise that the risk of not weaving may mean their transformation back to the demon, thereby imperilling the order of the everyday world.

Viewed as dangerous and marginal to society because they originated from the demon, women are controlled through weaving. It is said that a woman who is preoccupied and absorbed with her weaving will have little time to think wicked thoughts or commit sinful actions. It can thus be said that the making of cloth is linked to notions of feminine virtue and morality.

Perhaps as a bid to draw women into the sphere of religious activities, which their ancestors (the demons) rejected, religious beliefs are recognised and reinforced through women’s weaving. This is not the case with men’s weaving, which perhaps is because men listened to the Lama and learnt religion. This is also supported by the fact that Buddhism recognises men to be more spiritually advanced than women.

An interesting association between Buddhism and weaving is made through the female loom where the weaving process is associated with Buddhist beliefs and teachings. There is a song in which these analogies are made:

See the loom as precious,

That is good.

See the loom as a monk’s shrine room,

See the loom as the main shrine room in a monastery,

And you will grow.

See the square mat you sit on while weaving, as a meditation cushion,

That is good.

See the back-strap, which holds the loom around your back, as the casting of samsara behind you,

See the balls of weft passing from right to left as the monk’s kettle that serves tea up and down the monastery hall,

Hear the clap of the beater as the voice of Buddha reciting prayers,

That is good.

See the two wooden pieces of the front roller as the wooden covers of a religious book,

See the raising of the heddle while weaving as ascending in this world after death,

See the lowering of the heddle while weaving as pushing all sin down with your feet,

See the warp, which is soft and long, as the path to liberation,

And you will grow,

That is good.

The spiritual metaphors of the loom are clearly evident. The whole process of weaving becomes a continuous reminder of fundamental spiritual concepts, demonstrating the constant movement by Buddhism to penetrate and absorb every aspect of life.

Nurturing life

Mi rgyu la rtsam-pa spun

(The warp is like a person; the weft is like barley flour.)

Looms are described with reference to this popular expression. The saying implies that just as the weft gives the warp form and only then it becomes cloth, food gives the body life and only then can a person live.

The loom and its associations with conception and birth have been mentioned in the opening paragraphs. At one level, and corresponding to the proverb, in the female loom the weft which is seen as ‘food’ is analogous to a mother feeding the growing child within her womb. The more the mother feeds the child, the faster it will grow. Thus, a woman’s weaving symbolises birth as well as nurture.

The parts of a female loom are also associated with the analogy of a mother and her child. The beater (sdag) is referred to as the mother and the other parts of the loom, apart from the belt (sked), as her children.

As a result of the craft’s association with birth and life, the importance of weaving in a woman’s life is a measure of her ability to procreate; and many men’s choice of a wife is influenced by evidence of her accomplishments as a weaver. A skilful weaver is always highly commended by others; they will praise her by saying that she weaves quickly and neatly, and pays attention to detail. Those who do not weave are thought of as useless and unproductive. It is for this reason that it is imperative that a woman learns the skill of weaving, as it becomes a significant indicator in her general growth. Acquiring skill at the craft is an essential measure of the maturity and character of the developing girl, and good weavers are coveted brides.

It is perhaps interesting at this point to emphasise the weaving done by nuns. It is said that not only are nuns inferior to monks, they are also inferior to married women who owe their value to their birth-giving ability. At one level then, I suggest that a nun’s weaving may be one way through which she bridges this gap and accommodates to this disparity in her values. It can be said that a nun weaves the ‘threads of life’ and thereby plays out the act of reproduction which she is forbidden from participating in. In contrast, monks among nomads are not allowed to weave and a reason for this could be that the weaving process in the male loom is symbolic of the sexual union between a man and a woman; whereas celibacy is mandatory among monks.

Making connections through cloth

Nga-zha rgyu spun yin

(We are all warp and weft.)

Warp and weft is always there in the talk between husband and wife, or a mother and her children. It is there among relatives. After all, ‘we are all warp and weft’.

It is said that men and women weave threads that reflect kinship: patrilineal kinship is defined in terms of pha-rgyu (father’s warp) and matrilineal descent as ma-rgyu (mother’s warp). One’s progeny is generally seen as spun (weft)—the endless lengths of threads stretching out before the weaver. Thus, to be warp and weft is to know your family, to understand your lineage and to recognise your relatives on both sides.

At the time of a woman’s marriage, a gift-giving ceremony is held where her brothers fashion a rope out of khataqs (white offering scarves) and white cotton cloth. In tents, this is tied between the inner tent poles stretching outside if necessary, and in houses from the central pillar in the kitchen. The number of gifts a bride receives determines the length of the rope and is a subject of much interest and speculation. Almost all the gifts are made of cloth —some woven by the bride’s mother with help from the bride, others from relatives on her father’s and mother’s side. These are usually specified by the bride’s parents to their relatives well in advance of the wedding; the proximity of a relative to the bride usually determines the type and size of the gift from a piece of elaborately patterned silk fabric to a simple homespun bag (Figure 14).[xii] Thus, cloth moves within and reaffirms the most reliable reciprocal networks of affection and mutual obligation and establishes ties between people. It also cuts across households, demonstrating the links between members.

Fig. 14: A bride’s saddle bag (tshang-’dur). On weddings, the bride or her mother weave several bags such as this to hold her personal belongings, gifts and other household items gifted by her parents. (Photograph by Monisha Ahmed)

Once married, a woman continues to forge relations within her new home by weaving for her husband and his family. At the same time, they maintain links with their natal home through gifts of fabric on various occasions. It is said that women distribute their textiles so as to tie them into the widest possible web of social relations. Even in Ladakhi villages where women do not weave, it is said they spin threads that hold together the social fabric of society (Aggarwal 1994:229-30).

While women use textiles to widen their social circles, men’s textiles demonstrate lineage— defining the ties that establish the continuity and imperishable nature of the male line. Among nomads, men inherit the tent as well as a pattern of identification known as the yud from their fathers (Ahmed 2002:152-56). These patterns usually consist of stripes, rectangular blocks or circles with a dot representing a sheep’s eye (lug mig). Woven in various combinations and sizes, each pattern has a name and enables familial identification (Figure 15).

Fig 15 The yud, a man’s mark of identification, is represented through the patterns men weave on their goat and yak hair blankets—chal-li (left)—and saddle bags, known as lug-sgal (centre and right). (Photograph by Monisha Ahmed)

The elusive thread

The tent and yud are tangible woven objects that men pass down to their kin to define the linear immortality of their male line. Women have no such legacy. Their textiles, in contrast, are the more elusive social thread. Nonetheless, a woman does try, through her weaving, to link a number of households and to symbolically tie people together. One way she achieves this is by making gifts of cloth at the time of a wedding in her family, or on the occasion of a nephew’s hair cutting ceremony. She also forms new links through the progeny she gives birth to. But, like cloth, there is always the danger of these links becoming frayed. More so, in today’s fast changing world.

In the last few decades, many nomads have moved away from the Changthang citing a desire for a better way of life, access to new jobs and education for their children, among other reasons. Growing up, away from their grandparents and parents, the younger generation do not learn the age-old livestock and pasture management systems or imbibe nomadic practices essential to living in the harsh environment of the Changthang. While it is also true that the pashmina goat and the economic returns it brings, serves as an attractive incentive to remain on the Changthang (For more, read: Trade in Wool and Pashmina — Historic and Contemporary)

With readymade garments easily available, the need to weave cloth has also diminished. With it comes the danger of women reverting back to the demon and thereby jeopardising not just life on the Changthang, but also the very foundations of Buddhism.

Textile production amongst nomads contains evidence of the particularities of the place as well as its links to birth and life, and beyond that to the sublime. Whether or not the next generation of nomads will continue to recognise this importance remains to be seen.

Notes

[i] In other parts of Ladakh as well, stories relating to the creation of man and woman are tied in with the origin of weaving (see Ahmed 2002: 11).

[ii] It is the westernmost part of the larger Tibetan plateau by the same name, which extends 1,600 kilometres from Ladakh to the Chinese province of Qinghai in the east and includes most of western and northern Tibet (Goldstein and Beall 1990).

[iii] Groups are divided by their place of origin, each having its own chief and specified grazing areas.

[iv] Gesar is regarded as the legendary mythical hero-god in the Buddhist world of the Himalayas.

[v] With the clergy dissuading Ladakhis from wearing animal skins in recent years, the use of garments such as the slog-pa has decreased.

[vi] It is possible that the trouser came to Ladakh from central Asia where the garment is said to have first been developed in the third century BC, and is linked to the domestication of the horse (Anawalt 2007: 127).

[vii] Other scholars think the paintings date to the fourteenth century and were executed by Buddhist monks who inhabited the caves during that time.

[viii] The copying of textiles in paint on the ceilings probably derives from the custom of fixing actual pieces of cloth under the ceilings of rooms in Ladakhi buildings, partly as embellishment but also for the practical reason of preventing dust or mud particles from falling into the rooms below.

[ix] Though it is in Spiti, they provide one of the first descriptions of the backstrap loom and method of warping used there (Moorcroft and Trebeck 1841: 72-73)—both very similar to the technology found amongst the nomads of Ladakh.

[x] The word ‘pashmina’ is derived from the Persian word pashm which means wool. In its raw unprocessed form, pashmina is referred to as pashm and the word pashmina refers to the cloth woven from pashm. However, the words pashm and pashmina are often used interchangeably.

[xi] While no one was certain who this Lama was, some people said he may have been the great Indian yogi Padmasambhava who is well-known for bringing Buddhism to Tibet and quelling the demons who resided there.

[xii] A record is kept of the gifts a bride receives; later, when a marriage occurs in another family, the list is consulted so that an appropriate return gift may be made. Another purpose of the list is that should a woman get a divorce, all the goods mentioned in the list are returned to her.

References

Anawalt, Patricia Rieff. 2007. The Worldwide History of Dress. London: Thames and Hudson.

Aggarwal, Ravina. 1994. ‘Mixed Strains of Barley Grain: Person and Place in a Ladakhi Village’. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Anthropology, University of Indiana.

Ahmed, Monisha. 2001. ‘Subduing Demons – Women and Weaving in Rupshu.’ The Textile Museum Journal 1999-2000, 38 and 39: 4–25.

———. 2002. Living Fabric: Weaving among the Nomads of Ladakh Himalaya. Bangkok: Orchid Press.

———. 2005. ‘Textile arts of Ladakh – Nomadic Weaves to Silk-Brocades.’ In Ladakh: Culture at the Crossroads, edited by M. Ahmed and C. Harris, 66–81. Mumbai: Marg Publications.

———. 2005. ‘Brocade for the Buddhists: The Textile Trade between Benares and Tibet.’ In Textiles from India: The Global Trade, edited by Rosemary Crill, 9–26. Calcutta: Seagull Books.

———. 2010. ‘Dress and Ornamentation of the Inhabitants of Ladakh.’ In The Berg Encyclopaedia of World Dress and Fashion: South Asia, vol.4, edited by Jasleen Dhamija and Joanne B. Eicher. Oxford: Berg Publishers.

———. 2014. ‘From Benaras to Leh: The Trade and Use of Silk-Brocade.’ In Art and Architecture in Ladakh: Cross-cultural Transmissions in the Himalayas and Karakoram, edited by Erberto Lo Bue and John Bray, 329–347. Leiden: Brill.

———. 2014. ‘Duguma’s Legacy: Sacred Textiles of Ladakh.’ In Sacred Textiles, edited by Jasleen Dhamija, 26–37. Mumbai: Marg Publications.

———. 2015. ‘Fraying at the Edges: Textiles in Kargil Town.’ Stawa, 2 (5): 4–5.

Cunningham, Alexander. 1848. ‘Journal of a Trip through Kulu and Lahul to the Chu Mureri Lake in Ladakh during the Months of August and September 1846.’ JASB 17(1): 201–230.

Goepper, Roger. 1996. Alchi, Ladakh’s Hidden Buddhist Sanctuary: The Sumtsek. London: Serindia Publications.

Goldstein, Melvyn C and Cynthia M Beall. 1990. Nomads of Western Tibet: Survival of a Way of Life. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Khosla, Sunil. 1984. Art History of Kashmir and Ladakh. New Delhi: Sagar Publications.

Moorcroft, William and George Trebeck. 1841. Travels in the Himalayan Provinces of Hindustan and the Punjab (1819 – 1825). 2 vols. London: John Murray.

Myers, Diana K. 1984. Temple, Household, Horseback: Rugs of the Tibetan Plateau. Washington: The Textile Museum.

Petech, Luciano. 1977. The Kingdom of Ladakh. Rome: Instituto Italiano Per II Medio ed Estermo Oriente.

Wessels, C. 1924. Early Jesuit Travellers in Central Asia 1603-1721. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.