Abani Sen (1905-1972) belonged to that generation of artists who were shaking out of the cultural nationalism advocated by the Bengal School of Art, and became the harbingers of a new modern, seen in the post-Independence works of their successors. Though Sen represents an oeuvre that does not wholly participate in either of the more spectacular Indian art movements like the Bengal School of Art or the Bombay Progressive Group, he was instrumental in forming a link between them. Sen and his fellow artists, in fact, were working out the dialectic of the nationalist versus the modern Western style of painting.

While Sen was reasonably well-known in the art circuit during his time, national recognition did not come even many years after his death. This was partly due to the artist’s innate, reserved personality, and hence, the reluctance to engage with the press which could otherwise have propagated his art. It was also partly because he belonged to the period which was going through a transition and was unfortunately seen by the scholars as inconsequential or minor in the larger picture of events that shaped modern Indian art.

Abani Sen was born on March 18, 1905, in a small village called Taghoria near Dhaka, in erstwhile East Bengal. After finishing high school, he pursued Fine Arts from the Government School of Art, Calcutta (1926-1930), where he received the Director of Public Instructions Scholarship. It was here that young Abani and his fellow artists protested against the reorganization of the syllabus, and the arrogant attitude of the college administration during the term of Mukul Dey as the principal.

Gobardhan Ash wrote a detailed account of this event in his memoir Samagra Gobardhan Ash. Encouraged by their teacher, Atul Bose, they formed avant-garde artists’ associations such as the Young Artists Union and the Art Rebel Centre. Right after the protest in 1931, a few artists including Abani Sen, Gobardhan Ash, Annada Dey and Digin Bhattacharya organized an exhibition with the name ‘Young Artists Union’ at the Town Hall, Calcutta, in December that year. The show was successful, and the Maharajas of Tripura and Nepal, along with many eminent artists and journalists attended it (Ash 2005:112).

Brimming with confidence over the success of the Young Artists Union, Abani Sen, Gobardhan Ash and Annada Dey once again decided to hold an exhibition in 1933 on a much larger scale. Under the banner of Art Rebel Centre, artists such as Gobardhan Ash, Abani Sen, Annada Dey, Lalit Chandra, Haridas Ganguly, Samar De, Amar Dasgupta, Kalinkinkar Ghosh Dastidar, Khagen Ray, Suren Dey, Manoj Basu, and Robi Basu showcased their works. Atul Bose wrote the foreword of the catalogue where he said,

Our aim is to create an art that is strong, bold, virile and anti-sentimental, fearless in its desire for new adventures, a powerful advance-guard, which alone can save art in India now threatened by traditional conservatism and the habitual indifference of the public (Bhattacharya 1994:93).

The Art Rebel Centre was poised as a counter-point to the Neo-Bengal school, wherein Abani Sen and Gobardhan Ash were marked as influential exponents of Realism with a social commitment (Bhattacharya 1994:98). While the group rejected both the Bengal School romanticism and the art-school brand of academic realism, it adopted the contemporary visual language of European modern art movements. Although the group did not last long, the Art Rebel Centre was in a sense a forerunner of the Calcutta Group formed in 1943, whose motto was 'Art should be international and inter-dependent' (Mallik 2004). In 1947, Abani Sen was urged to join the Calcutta Group by its members, and Sen participated in their third annual exhibition.

Though not a radical by any means, Sen had established himself as a fiercely independent artist and chartered a roadmap which let him remain faithful to his art. In 1948, Sen moved to Delhi and joined the Raisina Bengali Higher Secondary School as an art teacher, where he worked till his retirement. Alongside, he taught at the Sarda Ukil School of Art for two years, and also at Delhi College of Art as a visiting faculty. He set up a modest studio in his Bhagat Singh market home, where he taught art to budding artists. Gradually his studio gained recognition as the only space in the city that offered studio practice facilities to young artists who were yet to establish themselves in the national scene. He was one of the legendary teachers of his time, and mentored a number of celebrated modern Indian artists. Among his prized students are today’s accomplished and renowned artists like Ranjan Sen, Manjit Bawa, Dulal Mondal, Ranvir Saksena, Suparna Ghosh, Rajesh Mehra, Kshma Shroff, Ramnath Pasricha, Manmohan Singh, Usha Biswas, Jagdish De, Surjit Kumar, and many others. Manjit Bawa said of his teacher,

'Abani Sen had given us the lost world of Gurukul. We spent the entire day at his home, painting, talking, and eating. He spent all his waking hours with us, teaching us, listening to us, telling us not just how to use color and line but how to view the world and make artistic sense of it.'[i]

Sen instilled in his students the same spirit of courage and empathy that he showed as an artist. In the foreword of the catalogue for an exhibition by his students under the banner of the Young Artists Society of India, Sen wrote,

'Artists are not escapists. Their endless effort is to overcome the limitations of man. The sight of suffering makes them erratic because that shatters their belief but there is no escape. The denial of the middle state robs them of their contentment. The supremacy of God being denied, love, becomes redundant and then the artist decides to lavish it in on the human race as a generous act of complicity' (Roop-Lekha 1960:75).[ii]

This exhibition was organized at AIFACS Gallery for helping the flood victims and Assam refugees, as is mentioned in the September 1960 catalogue.

In the capital, the art scene was vibrant, and Abani Sen was invited at regular intervals to exhibit at AIFACS, Lalit Kala Akademi, Chitra Kala Sangam and elsewhere. Abroad—he exhibited in Argentina, Afghanistan, Brazil, Chile, Cairo, Cuba, Canada, Russia, Poland, West Germany, Bulgaria, and the USA. Throughout his career, he received many awards, including the Governor General’s Plaque for the best painting in 1949 at the 18th Annual All India Art Exhibition of the AIFACS.

For paintings that were done fifty or more years ago, Sen’s works exude surprising modernity. As an artist, Abani Sen was almost equally realistic, romantic and a pure stylist. Tradition, inspirations, originality, and experiments are often feted in his works. He used a wide range of mediums—from pencil, charcoal, conté crayons, pen and ink, to watercolours, pastels, and oils. Certain experiences and subjects, themes and times, leave their traces on the growth of a painter’s work. Sen’s intense, romantic, and boundless sensibility comes out in the choice of those themes.

Many modern Indian artists like Nandalal Bose, Ramkinkar Baij and Benode Bihari Mukherjee showed deep attachment to animals and birds in their works, but Abani Sen probably was one of his kind during the last century who painted animals so extensively and expressively. Talking about the portrayal of animals in most of his works, Sen said, 'I enjoy painting animals. They do not know how to deceive us. They do not know how to play hide and seek.'[iii] This explained why he chose to focus on animals for the majority of his artistic output. At times, the rendering of the animal was done in a true to life manner, and at other times, Sen romanticised the form and nature of the animal using innovative pictorial tools. Vultures, kites, massive elephants, and cheetahs abound in his work, alongside deer, horses, and bulls. Sen stressed on expressing the associative attributes of his subjects. The bull in his paintings always exhibited a sense of strength and masculinity; the deer demonstrated speed, agility, and alertness; and the horse represented pride and freedom.

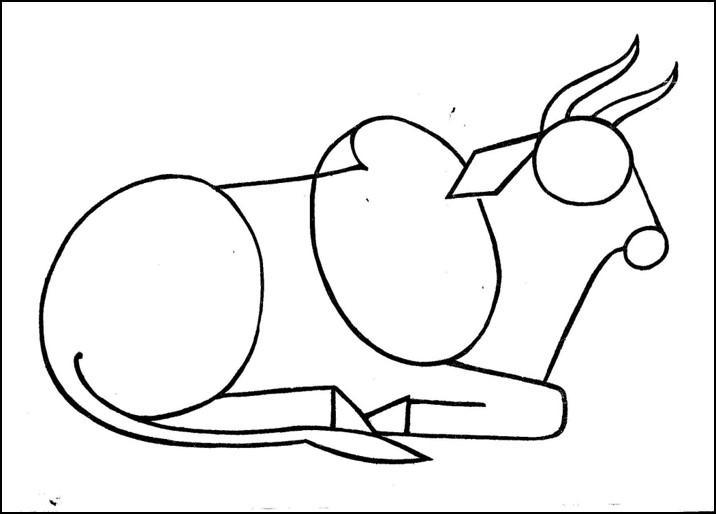

Sen’s works of animal studies are exceptionally brilliant when it came to bulls and horses who were his muse for most of his life. There is confidence, power and a sinuous grace in every frame. Sen seemed fascinated by the bull’s imposing symmetry which embodied a dark, hostile and brute force. He portrayed, except in a few instances, the lonely bull, deliberately choosing to depict an indistinct background to impart a sense of timelessness. This lends to his subject a dignity, specific to its existential identity. The massive animal is thus positioned in each frame, nearly always in its upright posture, and a tidy composite interaction with the pictorial space. Much of the expressiveness lies in their darkly shaded heads and humps, faces and sides, in the massively modelled muscles and limbs, with the calm yet brutal eyes. Such was Sen’s fascination with this animal that he also developed lessons for children on how to draw animals and birds in his series of eight sketchbooks called ‘Free-Hand Drawings for Children’.

Plate 1: Drawing of a bull from Abani Sen's art tutorial Chitra-Shiksha

As instructions in another children’s tutorial called Chitra Shiksha, he said,

'You will find that most of the birds and animals in this book have been drawn with the help of large circles, small circles or ovals, connecting them with a few lines, straight or curved. It is quite simple to draw most of the objects in this way.'[iv]

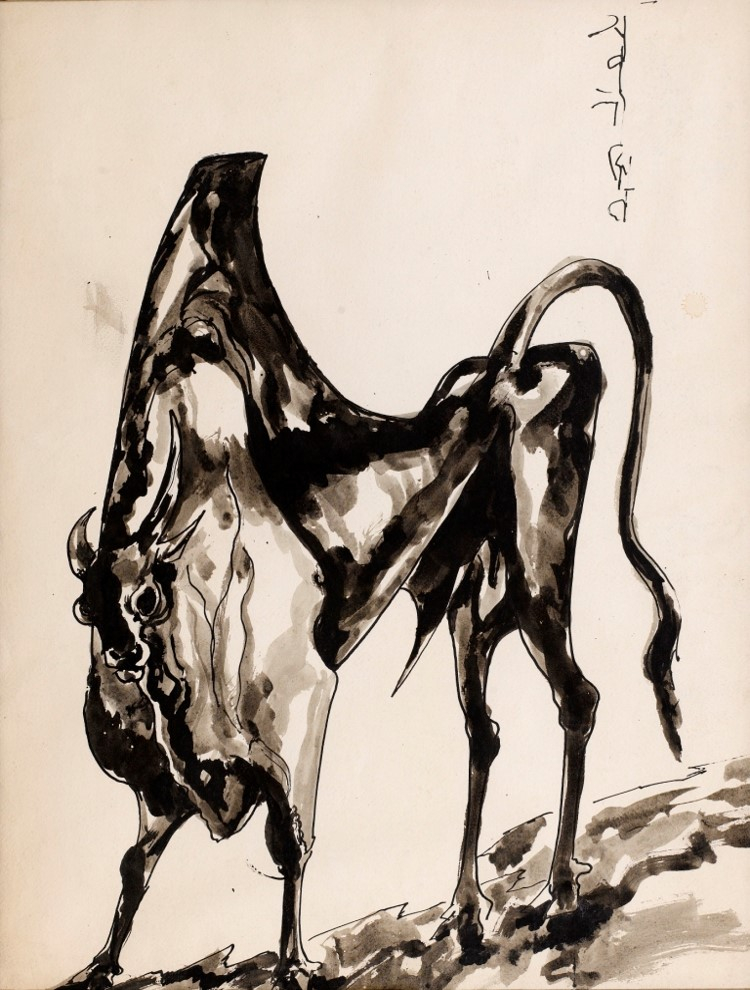

Plate 2: Stud Bull, ink on paper, 50 cm x 44 cm, 1959

The ink drawing titled 'Stud Bull', though painted much later, harks back to the most challenging period of Sen’s life in the 1930s when he was under financial strain. Here, the starving bull personifies Sen in his anguish and misfortune, in his grit and determination, and in his pride and dignity. The lone figure of the stud bull is spread across the vertical space diagonally, and is balanced by a very tall hump. Sen used angular lines to delineate the form of the animal projecting the hip bones, thighs, and the joints. The face, with its flaring nostrils, and ringed nose has a determined expression. The bull looks at the viewer with confidence. This composition in black ink on paper could be mistaken for a Chinese painting. Even Sen’s signature, though in Bengali, is vertical, like those seen in the Chinese scrolls.

Plate 3: Untitled, watercolour on paper, 54 cm x 34 cm, mid-1950s

In Plate 3 as well, the bull is massive, powerful and worthy of awe. The animal occupying centre stage is placed on a higher ground against a blazing orange background. Again, Sen has given the animal very distinct sexual organs, magnifying its virility. Its prominent hump and powerful musculature further highlight the animal's masculinity. The bull looks down from its high pedestal with self-assured confidence. The rest of the vertical coloured compartments in shades of blue, green, mauve and pink balances the pictorial space, apart from imparting prominence to the centrepiece.

Unlike the bull’s restrained power, Sen’s horses possess untamed energy. They are bursting in every limb with fierce, elemental dynamism, disciplined only by bold lines. In the study and observation of the horse, Sen made notes on its evolution and wrote,

'The earliest horse was a curious little creature no larger than a cat, and instead of the familiar hoof it had five toes on each foot. At a later stage, it lost some of its toes, and one well known early type had four on the forefeet and three on the hind feet. As it continued to develop, the number of its active toes became gradually reduced. And finally, after millions of years of slow development, nature produced the single-toed animal that for countless ages has been man’s willing helper.'[v]

Plate 4: Untitled, watercolour on paper, 56 cm x 38 cm, 1970

In Plate 4, two horses are seen wading through a riot of colours which stylistically aligns with the cubist approach. Divided into variously shaped compartments, the horses in the centre also appear to be a part of the same design. Sen outlined the forms in black and filled in the various sections in bold hues of reds, yellow ochres, greens, and blues. Interestingly, the brush strokes were in the same direction as the outstretched limbs of the horses, creating a sense of momentum, yet they look like delicate paper cut-outs.

Plate 5: Trio, Ink and watercolour on paper, 76 cm x 56 cm, 1961

Plate 6: Crying Horses, pen and gouache on paper, 56 cm x 38 cm, 1962

On the other hand, 'Trio' and 'Crying Horses' have a very foreshortened frontal view of the animals galloping directly towards the viewer and then plunging on the ground, screaming. All the horses in these two paintings have open jaws, flared nostrils, flying manes and tails, outstretched necks, faces turned skyward and a sense of agitation in their demeanour. The paintings suggest distress over some impending threat, the emotionally charged colour application further supporting it.

Dr Charles Fabri, eminent Hungarian Indologist, and an art critic, said, 'Abani’s work is far more powerful, more primordial and wild than of the exquisite masters of China.'[vi] It holds especially true for Plate 7 and Plate 8 from Sen’s animal series, where he explored the Chinese ink-and-wash style.

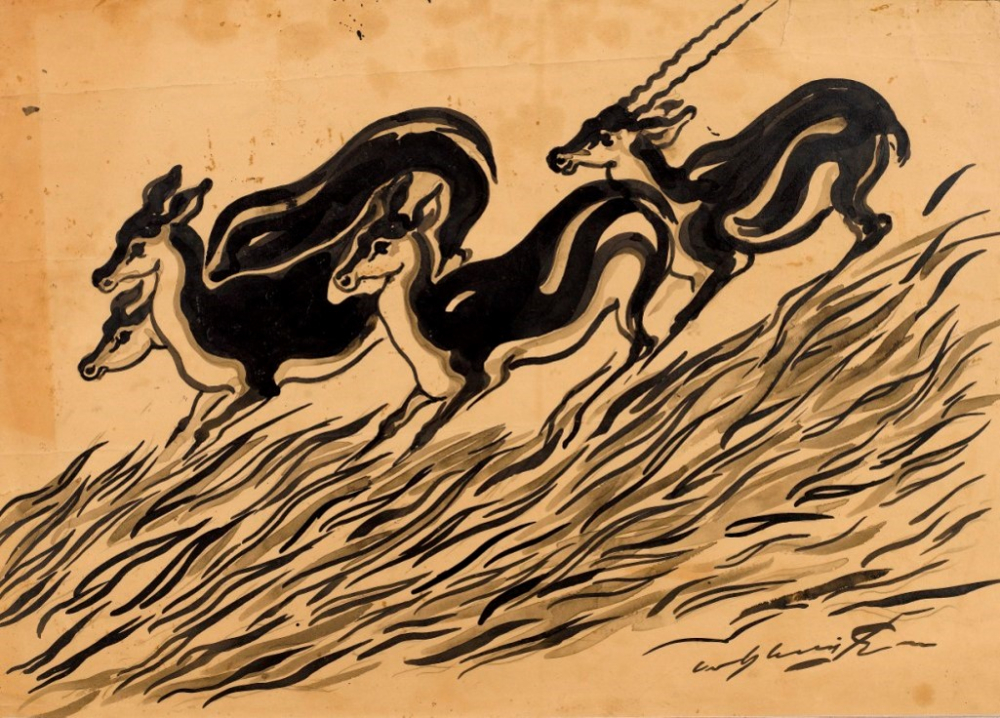

Plate 7: Speed, watercolour and ink on paper, 53 cm x 41 cm, 1934

The charming monochromatic painting called 'Speed', done in the early 1930s is simply throbbing with life. It shows a herd of deer running at high speed, cutting across the composition diagonally. The group consists of three female deer and a male identified by its antlers. The stirring motion of the grass in the reverse direction enhances the speed of the deer running downwards from right to left. The rhythmic wavy lines of the grass and the curvy bodies of the animals resemble the dark kohl lined beautiful eyes of the deer themselves. With just a few lines and tones, Sen delicately handles the subject and retained the spirit of spontaneity synonymous with the deer.

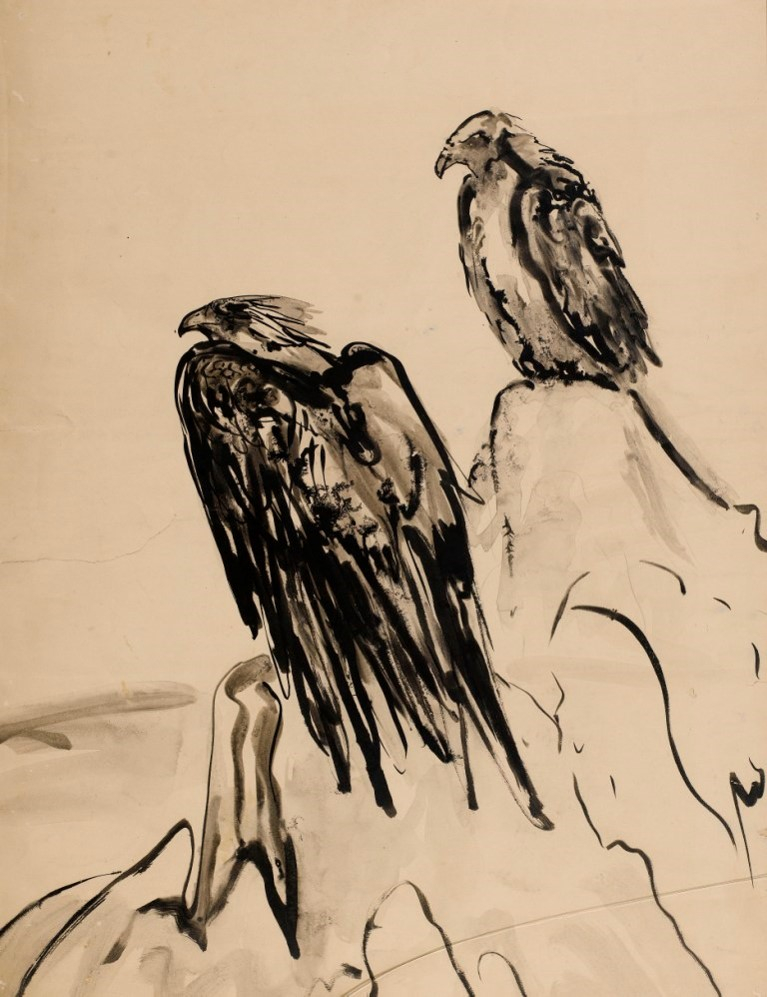

Plate 8: Eagle, watercolour on paper, 64 cm x 49 cm, early 1940s

Distinguished Chinese artists Qi Bashi and Xu Beihong, senior to Abani Sen, visited Calcutta in 1939 and showcased their works at a group exhibition at the Victoria Memorial Hall. Sen’s compositions of birds distinctly reflect their styles and techniques. In Plate 8, a pair of eagles are seen sitting atop a cliff keeping vigil either for prey or the eggs in their nest. A couple of lines are all it takes to hint at a rock. Sen concentrated on the eagle’s body, particularly the wings— sharp, vertical lines in close succession impart volume to the wings for the eagle in the foreground. There is an uncanny likeness between Sen’s ‘Eagles’ and Xu Beihong’s eagle paintings. Both display accomplished draughtsmanship, the boldness of execution and a sense of great creativity. Both used expressive calligraphic brush lines to animate their subject.

Plate 9: Goats, gouache on paper, 63.5 cm x 38 cm, 1954

Sen’s striving for redefining conventions led him to produce works like Plate 9. He was intrigued by the pictorial language of Indian folk art and interpreted this style quite freely, tapping the strength of his ‘folk roots’. His paintings such as these were filled with a visual appeal of an intensely absorbing nature, and vibrant designs evolved by the tradition of rural Bengal. There is an element of modern abstract colouring in the background while the elongated forms of the two goat figures echo design awareness seen in the folk art tradition of Bengal. The surrounding is a kaleidoscope of colours, ranging across rosy brown, salmon, turquoise, mint blue, steel blue, slate grey and black. Sen’s representation of animal forms in curvy moon shapes, circles and lines had become rather stellar by the end of his life. His works have a straightforward visual appeal which converses with the viewer.

As for the human figures of Abani Sen, some themes were recurrent in his oeuvre—the bathers, couples, portrait studies, and mother and child. His emotional themes range from love, intimacy, affection, and bonding on the one hand—to solitude, loneliness, regret, boredom, and resignation on the other. He experimented with sexuality, mortality and human frailty. In doing so, he tried out different styles, surfaces, and symbolism.

In his portrayal of bathers, Abani Sen was reinterpreting a long tradition of composition with nude figures in the landscape, by both western and Indian artists. With bathers, Sen attempted both an intimate and a detached study of the subject. For many of these images of women, he adopted un-idealized features to show a variety of physical and emotional states. He often painted two, three, or groups of nudes in various poses, dovetailing skillfully to create a captivating ensemble of female figures in nature. These multi-layered works are an analysis of the complexities of human emotions apart from being brilliant studies of the female nude. Each of these faceless women tell a story of vulnerability, unbridled sexuality, or female bonding, through as banal an act as bathing.

Plate 10: Bathers, oil on canvas, 122 cm x 88 cm, 1962

Plate 10 is a beautiful oil painting of bathers which flaunts a figurative composition of several nudes grouped in and around a river. Sen treats the bathers, not as personalities but forms in nature. The painting reveals Sen’s fascination for Cezanne’s figurative works. Like Cezanne, Sen constructed the landscape so that it functioned as a stage. The motif of a group of bathers in a landscape enabled the artist to tackle questions about the ideal of harmony between man and nature. This composition is divided horizontally into three distinct zones, each with a purpose with regards to the subject. The group in the foreground has figures that are either preparing to go for their bath or are coming out of the water. The middle-ground is the river itself where two or three figures, drawn very sketchily, are swimming. In the background, there is a group of women who are either resting or waiting. Interestingly, though these bathers exist in the same environment, neither of them communicate nor overlap. The majority of the figures are in profile or back view, concealing their sexuality. Right on the foreground is the figure of a woman whose open pose contrasts with that of all the other figures in the painting. There is no attempt by the artist to cover her modesty by either crossing her legs or covering it with her hands. She, in fact, is aware of the viewer’s gaze. Just behind her are five large nude figures that are in back view, evoking a mood of voluptuous languor. The curve of their heavy hips is exaggerated to mimic the dip and the swirl of the river as well as the ground. Also, these five figures wear their hair in an identical manner with their heads hanging downwards, making the viewer wonder about some symbiotic relationship within this group. The one standing nude appears to be emerging out of the water—her wet, open hair spread behind her and here too. Sen is not at all skittish about the lower half of this frontal nude.

Even as the bodies seem to have captured the greatest share of his painterly caress, the sky, the ground and the river are by no means subordinate to them. Everywhere in the whole plane of the picture, modulations of colour are found balancing and contrasting each another. This finds its counterpart in a form of outline, the aim of which is not to isolate the object it encloses, but instead to form the connecting link between two contiguous colour values. The outlines of the figures are roughly mapped out in black strokes, and they convey a marvellous sense of volume. The masterly skill Abani Sen had achieved in his mature years, is evident in the way he tackles the large featureless area of the ground, deftly transforming it into a vibrant series of colours. With loose strokes of yellow ochre and green laid beneath a thrilling sequence of rich strokes of blue and black smeared with the brush and the palette knife, he made the texture of the ground resonate within the general harmony of the picture. The very blue river seems to be reflecting the sky.

Plate 11: Couple, watercolour on paper, 61 cm x 48 cm, 1959

The monochromatic watercolour painting of a couple in a drunken stupor in Plate 11 is a portrayal of a couple in modern times. This work at first looks like a purely abstract painting with some strong play of colours in black and white. Then, the forms in the centre slowly emerge. It is a figure of a woman holding a glass leaning against a man with a flower in his hand. The glass she holds is tilted, and the liquor is spilling out—she perhaps is in a semi-conscious state. Interestingly, while she leans on the man, he has his head completely tilted backward unnaturally. The couple is embraced in an intimate pose without facing each other. It is not very clear whether the couple is clothed or naked. The woman is wearing a veil on her head, and there are lines suggesting drapes, but one cannot be very sure. The artist has deliberately left their state of undress to the viewer’s imagination. There is complete lack of any pictorial element in the surrounding, except for the moon which suggests that it is night and the couple is sitting outdoors. The presence of the moon helps in accentuating the passionate tone of the composition.

In the genre of landscape paintings, Abani Sen mastered everything necessary for a good picture: colour, draughtsmanship, graceful composition, poetical sentiment, and truth to nature. He was known to be consumed by the beauties of nature from his early childhood. Instead of travelling far and wide to paint variations on the standard ‘picturesque’ themes, Sen found subjects in his native landscape. The landscape with its low lands and rivers made a deep impression on his young mind. He learned to paint the landscape, the birds and the beasts, long before the human portraits or the sophisticated still-life. After moving to Delhi, he frequently went to Shimla and took inspiration from the Himalayan terrain. Bengal’s unique countryside with placid greenery and boats by the riverside or the serene locales of Shimla became regular subject matters of his paintings. In the Bengal landscapes, Sen favoured the horizontal format of the composition to portray the lush greenery of the river basins of Bengal whereas he chose the vertical format of the composition when he painted the lofty hills of Shimla.

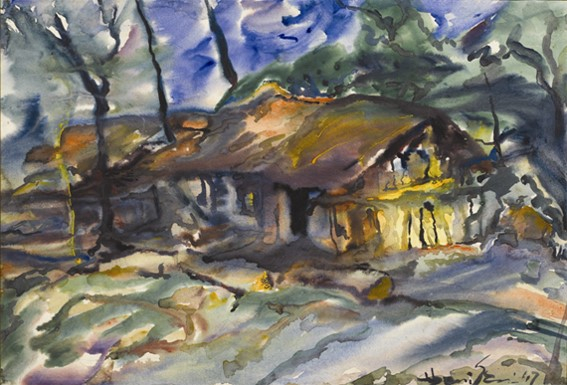

Plate 12: Village Scene, watercolour on paper, 54 cm x 38 cm, 1947

The watercolour painting called 'Village Scene' takes the viewer back to Sen’s native village in Dhaka. It has a sense of the rural setting, typical of East Bengal, where the monsoons are abundant. This is a humble painting of a couple of houses and a few trees against the late evening sky evident from the dashes of cerulean blue used for the sky. Painted wet on wet, the composition is loosely rendered. It gives an impression of looking at the scene through a rain washed windscreen. Nonetheless, Sen manages to retain the intensity of the colours. The vivid yellow on the side of the house and the small window in the front implies that the lanterns have been lit after the sun has set. But strangely, the foreground is very lightly coloured for it to be night time. Or is the artist suggesting a moonlit night?

Plate 13: After a Long Day, pastel and gouache on cardboard, 69 cm x 56 cm, 1945

'After a Long Day' creates an image of thoughtful stillness on the banks of the river Hooghly. Compositionally, the painting is divided into two horizontal strips with a horizon line dividing the sky and the earth. The lower half is further divided by a diagonal line separating the river and the ground. This balanced composition draws the viewer’s eye to the brightly lit boats at the centre of the painting, which are anchored to the shore. The canvas roofs of the boats are lit in yellow light from inside. After a long day, the boatmen are perhaps cooking, eating and resting inside their makeshift homes. The ground is coloured in muddy brown, mossy green and black, in contrast to the cobalt blue of the sky. By rolling a yellow pastel sideways on the surface of the painting, Sen sprinkles the yellow light from the boat across the sky as well as the land. The lively evening sky becomes the sensitive backdrop for the composition. The pale grey water takes on bits of colour from the sky, the ground, and the boat.

Easily accessible from Delhi, the beautiful environs of Shimla kept luring Sen time and again and became a recurring subject in his works. Shimla presented him with a landscape which was very different from that of Bengal. With its undulations, plummeting cliffs, basins and clearings seen from above, mountain roads descending vertically etc., Sen articulated the space in the Shimla landscape more dramatically.

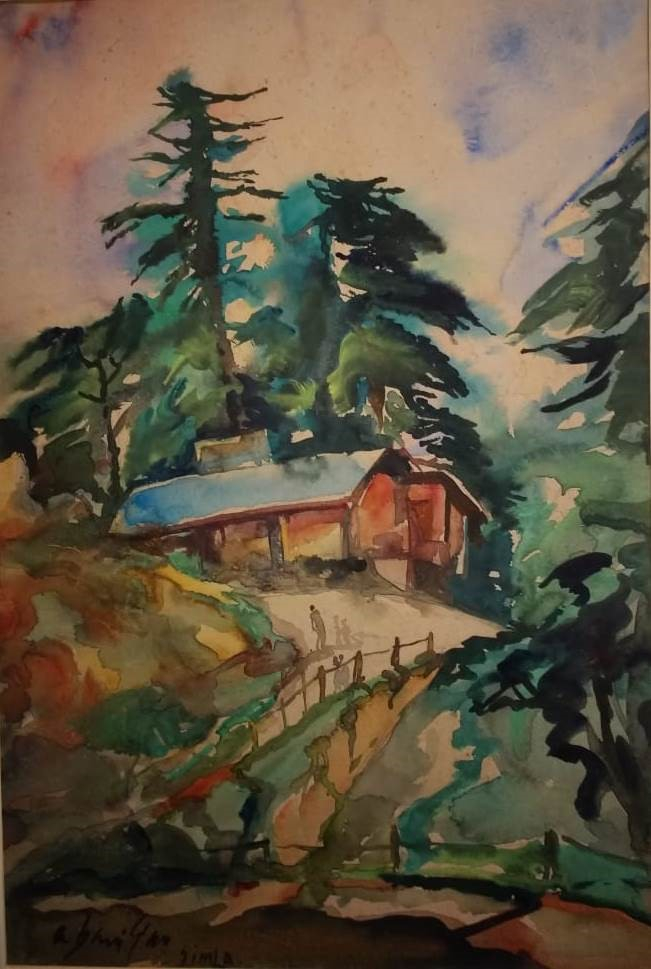

Plate 14: Untitled, watercolour on paper, 1950s

The picturesque image of a house with winding roads and deodar trees in Plate 14 instantly strikes a chord with those who have visited Shimla. In this work, after the initial drawing in pencil, the paper surface is made wet first, so that the base colour, when applied, begins to flow and merge and is then left to dry. After that, the vibrant colours are added in an impressionistic manner, like the grassy patch on the slope below the house and the tree beside the road. As a final touch, with a very fine brush, thin lines in black, grey and brown are used for outlining the trees and its branches, the house, the railings and the road. The verticality of the painting, the upward tilted ground, the irregular horizon of the landscape—they do not merely describe an actual site but also distil the essence of that locale.

Reviews from leading newspapers gave an account of how the art patrons perceived Sen. It was observed that his creations, for all their energy, were inherently introspective. Prizes, citations and accolades notwithstanding, fame eluded Sen in his lifetime. He and his works were known only to a select circle of artist friends, students, and the cognoscenti; for art lovers, he somehow remained on the periphery. Being averse to fanfare and publicity, he did not exhibit as widely or as frequently as was perhaps needed. While acknowledging him as a master artist who responded to incoming metamorphoses of the Oriental and Occidental ethos in his work, true recognition was accorded to him as a teacher non-pareil.

Notes

[i] A Retrospective of Works by Abani Sen. 2001. Exhibition Catalogue, 11. New Delhi: AIFACS.

[ii] This catalogue is in possession of the artist’s family.

[iii] This undated quote of Abani Sen, written by him, is from his sketchbook, found in the artist’s family archive.

[iv] Abani Sen, Chitra-Shiksha (New Delhi: Printed and Published by Usha Sen). The book is undated, but in reference to other similar books of the same period, it can be dated to early 1950s, or more precisely 1954.

[v] Notes from Abani Sen’s sketchbook from 1952-61 from the artist’s family archive.

[vi] The Sunday Statesman. 1951. ‘Abani Sen: Paintings and Drawings’. The Sunday Statesman, New Delhi, December 16.

References

Ash, Gobardhan. 2005. ‘A Protest Letter to Pradosh Dasgupta’ in Samagra Gobardhan Ash. Calcutta: Raktakarabi.

Bhattacharya, Ashok K. 1994. Calcutta Paintings. Calcutta: Director of Culture, Department of Information and Cultural Affairs.

Mallik, Sanjoy. 2004. ‘The “Calcutta Group” (1943-1953).’ In Art & Deal (online at: http://artanddeal.in/cms/?p=3472).

Sen, Abani. 1960. Foreword to Roop-Lekha, XXXI (2), 75. AIFACS: New Delhi.