The Edakkal [1] Rock is on the crest of a hill known as Ambukuttimala belonging to the Western Ghats, about 4,600 feet above the sea level and situated about 10 km south-west of Sultan Battery in the Wayanad district of Kerala. It is a prehistoric rock shelter formed naturally out of a strange disposition of three huge boulders making one rest on the other two with its bottom jutting out in between and serving as the roof. Edakkal literally means a stone in between. The combination of the curves and protrusions of the boulders in the alignment is such that it virtually brings into existence a two-storied natural cleft. The lower storey can be entered through an opening of 5x4 feet into the interior; measuring about 18 feet in length, 12 feet in width and 10 feet in height, which has a trickle at the corner opposite to the entrance. A passage upward leads to a small opening on the roof through which one climbs up to the next storey whose entrance is about 7x5 feet. Its interior is about 96 feet long, 22 feet wide and 18 feet high. There is a big opening at the right-turn corner of the roof since the roofing boulder does not touch the facing wall, allowing enough light into the cave. The right and left walls of this upper cleft are replete with figures made in a mode difficult to be classified as engraving or carving or etching.

The discovery of the cave and its identification as a prehistoric site were quite accidental and part of the colonial British game hunting. F. Fawcett, the then superintendent of police of the erstwhile Malabar was the discoverer, who on a game-hunting trip to Wayanad happened to see a neolithic celt recovered from the coffee estate of Colin Mackency in 1890. An enthusiast in prehistory, Fawcett went around exploring the Wayanad high ranges, which eventually led to the discovery of the Edakkal rock-shelter in 1894. He identified the site as a habitat of neolithic people on the basis of the nature of representations on the cave walls, which appeared to him as engravings made of neolithic celts. He was able to identify certain representations as human and animal figures and magical symbols.

Apart from the passing references to the Edakkal cave by various authors on prehistory, there is no exhaustive archaeological study of the site.[2] Strangely enough, it did not attract the attention of archaeologists, despite its representational richness and uniqueness with no parallel anywhere in the world. Naturally, there have been no serious and methodical interpretations of the archaeological context and meanings of representations on the cave walls. The art-historiography of India could generate very little new knowledge about their styles and contents though it repeatedly emphasised the unique place of the site on the map of world prehistory. This historiographic desideratum justifies the attempt here to study morphology and decipher the meanings of the representations on the cave gallery. However, real access to the meanings needs a computerised database and appropriate software enabling global comparisons of prehistoric pictographs.

Morphological studies do not require archaeological knowledge about the context of the site since they, in the first instance, are concerned only about the structure and composition of the visual imagery. Their primary concern is about the structuring principles of objects in the representations, their elements of production and the determinate pattern of relationships. But the study of meanings necessitates at least a tenuous knowledge about the archaeological context of the representations to situate them within the relevant material matrix of social existence. Except for the discovery of a few neolithic celts from the area around the site and the objectively verifiable fact that such engravings/etchings can be made of the celts, we have no direct clues to the archaeology of the figure works under consideration. Actually, one has to do a detailed plotting of the area with points of archaeological finds, passages and routes connecting highways, cult sport, old and new settlements and so on, which is yet to be done in the case of this rare archaeological site of Kerala.

The Edakkal cave site is on an ancient route connecting the high ranges of Mysore to the ports of Malabar. Also, we know that the route was in continuous use during several historical periods. But much of the historical importance of the site remains to be unravelled. We do not know what the site overlooks or hides, though it is easy to describe how accessible or inaccessible it has been in the past by looking at the present geography of the region. This would mean that much of what a student of history is looking for about the site remains inscrutably hidden.

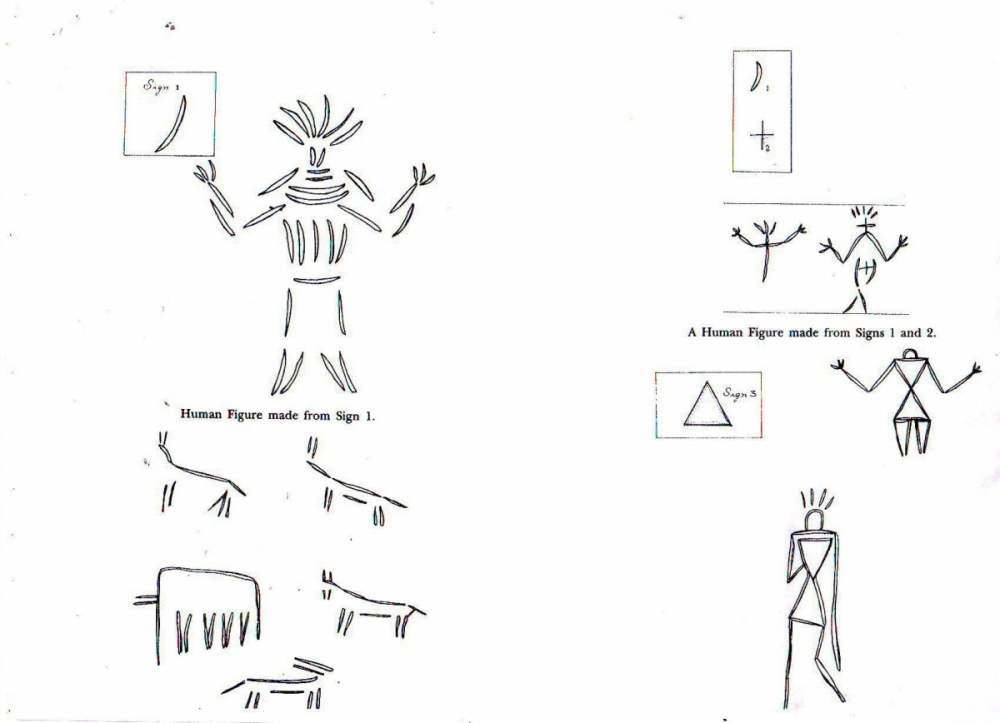

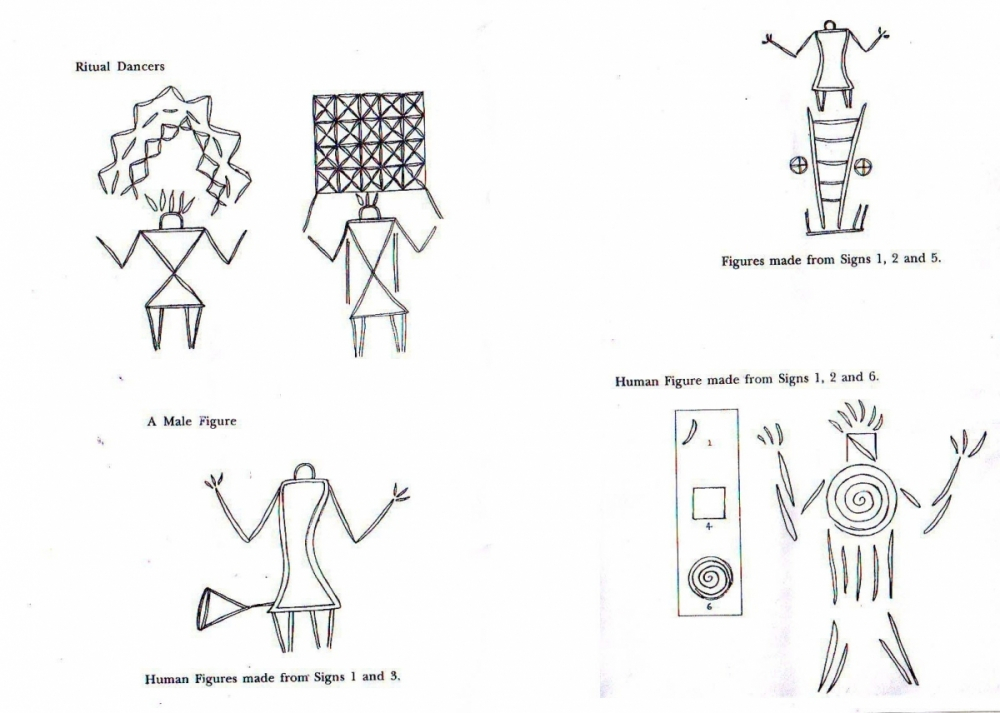

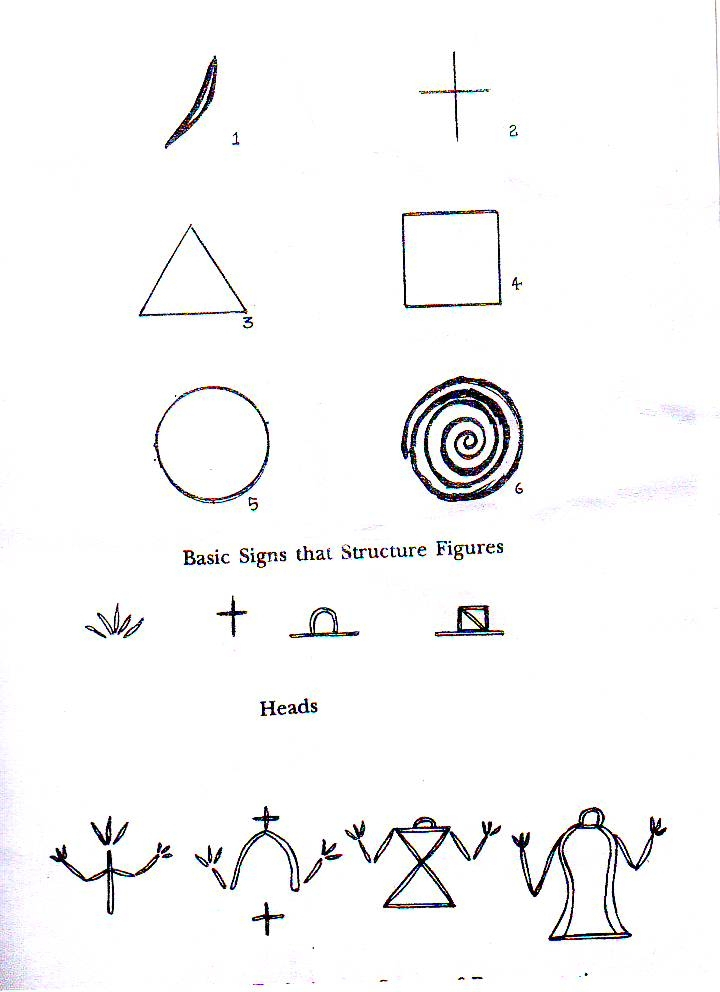

Before one attributes interpretive meanings to the representations, it is essential to know the mode of objectification and the elements of object production ensuring heuristic control. It is in this context that the study of morphology becomes extremely important. What we have attempted here is first to describe formally and structurally the representations on the cave walls by discovering their elements of production. In such a perspective, the representations across the surfaces of the cave walls can be reduced to six basic elements of production: canoe, cross, triangle, square, circle, and volute.

The first element, i.e., the canoe-like incision seems to be the most elementary of all signs and the starting point of the representation in the gallery text. In fact, it could be the initial sign of any engraved representation of prehistoric times, since it is the natural mark resulting from the process of grinding an axe or celt into the finish by rubbing harshly on the surface of the rock. The other signs such as a cross, triangle and square are geometrical signs developed from the primary sign with which the prehistoric people were familiar. Circle and volute are tertiary signs resulting from the faculty to mediate the primary and secondary signs for the construction of figures.

The objects of the gallery text on the two walls are as follows:

Wall 1

1. a prominent human figure with a headgear

2. a back view (?) of a human figure with headgear and other decorative elements

3. a human figure with an elaborate head-dress

4. a tall human figure with headgear

5. an elephant, a wild dog, a peacock and a couple of wild dogs

6. plants and flowers

7. a human figure with a long hand shaped like a jar

8. a human figure with a square head-dress

9. a wheeled cart, and

10. a few geometrical signs

Wall 2

1. a few geometrical signs

2. a few male and female figures

3. a triangular sign representing a human figure

4. a human figure on a wheeled cart, and

5. a human figure with a conical sign attached

As regards the genre of the art activity at Edakkal, it is a straight line geometric schema which does not require any particular skill; rather, patience is developed as an imperative of the collective need. The linear geometric schema could be a development over the rigid style of combining primary sign into the images. The images are not made through the linear representation of the physical features or anatomy of the object but through a suggestive strategy of impressionistic marks that combine themselves with their shadows to make the images. It is in fact a strategy of representation by itself enabling the making of images through a combination of incisions and their shadows, seemingly in the firelight rather than sunlight.

There are two distinct styles of representation explicit in the Edakkal rock gallery: one is the style adopting solely the primary sign and the other is the one adopting primary, secondary, and mediatory signs for the construction of figures. Similarly, there are two states of evolution perceptible across the representations. One is the primary stage of a relatively simple representation through the ordering of independent signs. The next stage of evolution seems to be that of the mediatory style which has the advantage of avoiding disjunctions in image-making. In the representation of human figures, there are examples of figures made solely of the primary sign; figures made of primary and cross signs; and figures made of primary, secondary and mediatory signs. The use of the triangle sign is dominant in the case of certain figures. In the assemblage of figures, there is a movement of both the style and strategy from simple to complex. As we move from the simple to the complex, the use of mediatory signs increases and gradually the breaks and gaps between the constituent signs of figures vanish indicating a continuous stylistic evolution. There are representations showing relatively earlier and later stages in terms of the evolution of style. The representations on Wall 1 are of primary style/strategy with no attempts at the mediation of signs, whereas the portrayals on Wall 2 are primarily of secondary and mediatory style/strategy.

It appears that in the case of the construction of evolved figures some new implements other than celt was used. It was probably an iron implement as indicated by incisions which are relatively thinner and evenly deep. The evolved style of representing a human figure is seen associated with a wheeled cart. Seemingly the wheels are spoked and different from the primordial ones made of planks. But the cart is shown using the primary sign. These do not seem to be random images of mutually exclusive nature, though several of them could have been added on to from time to time. There is an overall ordering principle upon which the assemblage of images signifies a determinate pattern of relationship based on centrality versus marginality and projection versus recession of the objects of representation.

With a general idea about the techniques of art production, we have tried to describe what do the representations look like. We know that looking at art can give the viewer a distinctive pleasure and also we know that this response reflects an important feature of art as far as society is concerned. Beyond what the representations appear to us lies what they meant to the society of their times. What is historically real about the effective response to art is our central concern, however elusive it is. There is little that can be said with certainty about the historically real effective response to a given artwork. Nonetheless, certain anthropological concepts and psychological theories of eminent scholars, who have been grappling with the question of deciphering the historically specific meanings of art, do help us say something about this elusive or mysterious aspect of ancient art.

The general anthropological assumption is that perceiving art as an object of gratification has little relevance to the case of prehistoric representations since they were not consciously created artworks but the structured outcome of a socially indispensable activity fulfilling certain significant purposes of life. They were part of a contemporary subsistence strategy and were not primarily the result of aesthetic response. The argument is that for the prehistoric people it could hardly be an activity for the sake of art. Anthropological studies on prehistoric art reiterate in one voice that the subject matter for the art of prehistoric people had been that what was of utmost importance to their life, i.e., the question of food, reproduction, combat, domination or submission. But within this broad ideational unity, there are hermeneutical as well as methodological differences ranging from the functionalist approach of Henri Breuil to the structuralist perspectives of Leroi-Gourhan, showing prehistoric art as part of the sympathetic hunting magic and the result of a determinate structuring.[3] This idea is central to the interpretation attempted here.

On Wall 1, the tall human figure portrayed on top at the centre could be the representation of a deity; the prominent human figure with headgear occupying the centre looks like a chief, and the human figure portrayed in projection facing the central figure seems to be a ritual dancer. Other human figures with head-dress also seem to represent ritual dancers. The elephant, antelopes, wild dog, peacock, plants, and flowers represent the forest. The wheeled cart perhaps indicates the traffic of goods, probably in the context of the interaction between two different cultures in terms of ascriptive or customary exchanges.

It is not clear whether all these representations should be viewed as a single cultural production or as mutually autonomous ones. We would argue that the representations seem to have been added from time to time for serving the purposes of a changing society within a broadly uniform culture. Art is such a practice which once produced is reproduced, added on to, superimposed, re-appropriated and reified to suit the changing needs. So it becomes extremely difficult, if not impossible, to conclusively make out whether the cluster of representations as a whole belongs to a single culture. However, if we take whole representations as the single collection of codes of a changing culture, they do signify the various developmental manifestations of the culture. Across the variety of representations of independent objects, one can discern the binding code of a changing culture. Beyond the appearance of independent representations or figures, there is an interpretive realm of paradigmatic traces which we discover through a comparison of figures. For example, above the human figures, we discover a layer of ideas like deity and laity mediated by ritual dancers identifiable through a comparison of their forms.

The representations collectively signify a scene of ritual festivity of a tribe inhabiting the forest and subsisting on hunting and shifting cultivation. It could probably be the archaeo-anthropological context of the coexistence and interaction of the neolithic and iron-smelting societies that is reflected in the structure of relations in the totality of representations characterised by the presence of a simple style at the core and a relatively evolved one at the periphery. The representations at the core seem to be neolithic and those in the periphery, megalithic providing a tentative dating of the gallery as late first millennium BC. However, the representations, despite their different points of origin in time, are organically woven into a single entity due to the unifying force of continuity embedded in the changing culture. In short, the representations seem to be symbolic of a new Stone Age society in transition.

It is true that the representations in prehistoric art signify a realm of strange meaning intelligible only to the people of their times, but it is equally true that they signify a set of meanings which are intelligible only to us. We discover the meanings by analysing the social causes of the development of gratuitous complications, fantasy, in the artworks. However, there is the lurking danger about interpretations taking too much for granted in building semantic structures often never to have anything to do with prehistoric reality. Following Claude Lévi-Strauss and Frederic Jameson, we identify the contradictory dynamic of the relatively simple forms of tribal organisation as the generative source of strange decorative and contravening forms of duality in the representations of the Edakkal rock art. Jameson observes that artworks of gratuitous complications can come into existence only through a process of alienation and estrangement in society. In an unfallen social reality there is no chance for the development of fantasy production in art because there is no contradictory dynamic that keeps the people perplexed. The existence of contradictions and the lack of remedy at a social level, which generates a confusion and disquiet in the people, leads to the creation of fantasy art. It is the projection of societal contradictions by a people who have the resolutions within them but are not able to objectively formulate them into the imaginary.

Such an explanatory framework helps us interpret the graphic decorative, huge head-dresses and contravening duality in the representations of Edakkal as fantasy production of a late neolithic society perplexed at the changes in the wake of the introduction of iron by an alien society. It is reminiscent of a society passionately seeking to give symbolic expression to the resolutions which it is unable to conceptualise at a social level and live them. Alving Walfe has suggested that in Africa at least the amount of fantasy art production by a people is roughly proportional to the extent to which they are divided by social cleavages.

Regarding how the gratuitous complications of art acted on contemporary society, many scholars like Douglas Fraser, Lévi-Strauss, Payne Hatcher, Robert Paul, György Lukács, and Frederic Jameson have suggested that fantasy production as the imaginary resolution of contradictions helped maintain cultural stability required for a developing society. Lukács and Jameson viewed it as part of the containment strategy.[4] Functionalists like Durkheim, Radcliffe-Brown and Talcott Parsons considered such manifestations of art as part of the solidarity maintaining mechanisms of a transitional society. However, what emerges on top of all in these theories is the symbolic objectification of an urge for social cohesiveness in a situation of flux.

Viewing the gratuitous complications of the Edakkal rock art in this perspective, we get the impression that the society behind it was facing the transitional crises and contradictions which were insurmountable to the people who in the form of fantasy production found a purely imaginary resolution in the aesthetic realm. George Harley suggests that sometimes abnormal situations due to severe transient developments in the system could also give rise to complexity in prehistoric art. The complexity appears as a psychic resolution of perplexing circumstances. We have no evidence for any such ecological crisis of the past that had affected the region. Art historian Ernst Gombrich observes that wherever neolithic societies had come strongly under the influence of metal-using cultures, the former's art had been significantly altered or modified. This seems to be true of the rock art under consideration wherein the evolved linear representations, which are obviously modifications on the earlier style, resulted probably under the influence of iron using culture. It is important that down the hill there are several megaliths around the site surviving to our times as archaeological proof for the existence of the iron-using people.

There are certain symbols and exotic marks all along the representations which seem to have meanings and functions of their own, ranging from the explicit to the implicit and symbolic. Interestingly, all these graphic signs or symbols are found on the variety of megalithic pottery recovered from southern India and Sri Lanka. Moreover, the genre of art involved in the production of graphic signs is the straight-line geometric schema which we have identified as an evolved stage of developmental complexity. The symbols may not always stand for a single meaning everywhere, but they do often signify one or the other among a cluster of closely related meanings in all culture. This is particularly true in the case of libidinous symbols. Sexuality and reproduction are literally vital topics in all societies and symbols of these primal themes have universal similarities all over the world. There are two very clear libidinous symbols of genitals among the graphics of Edakkal. They are shown explicitly as meaningful symbols by being attached to human figures. All the graphic signs do not seem to be symbols conveying specific meanings. They could be mere decorative additions to the magical significance of the central images.

Edakkal rock engravings stand out as distinct among the magnitude of prehistoric visual archives of paintings and graphic signs all over the world. It is the world's richest pictographic gallery of its kind. The images and signs jointly signify a strategy of combining deep incisions and their shadows in firelight for generating three-dimensional visual effect.

Notes

This study is an outcome of the extensive filed work undertaken jointly with M.R. Ragahava Varier.

[1] The area is now covered by coffee and pepper plantations and inhabited by immigrants from the central and southern parts of Kerala, whose history does not go beyond the present century. The aboriginal tribes, Paniyar and Mullakurumbar, survive these days in small pockets. It was a forested area till the late 19th century when the British deforested the site for coffee plantation. The entire eastern slope of the hill was converted into a coffee estate by Colin Mackency, the first surveyor general of India under British rule, toward the end of the 19th century. Despite the new estates and settlements which have led to large-scale deforestation, the environment still keeps the traces of erstwhile backwoods helping us in visualising the locale as an ideal habitat of prehistoric people.

[2] Ever since the publication of Fawcett's report on the site, other colonial indologists like Hultzsch and Brucefoot referred to it. Panchanan Mitra makes a passing reference to the representations assigning them to the early Neolithic on the basis of their comparability with the mesolithic engravings at Ghatasila in Chhota Nagpur (See Mitra 1927). There are a few passing references in H.D. Sankalia (Sankalia 1978) on the Edakkal representations. In the absence of excavated studies and reliable dating, he endorses the observations of Fawcett (83, 88, 90). There is an interpretative study that relates to the representations to the primitive sun myths and compares them to the representation of sun myths in the rock art of Steria on the Alips. See Dike Olaph Tilner, Felsblid and Mythus, 1980.

[3] The interpretation of prehistoric art as sympathetic hunting magic had been widely recognised by the community of archaeologists and art historians (Graziosi 1960, Ucko and Rosenfeld 1967). There is an increasing realisation about other semantic possibilities now with the structuralist studies on the prehistoric art (Leroi-Gourhan 1967; also see Bouissac 1994: 100, Nadin 387).

[4] The concept of containment strategy is developed by Lukács (Lukács 1971; also see Jameson 1981: 53, 210).

Bibliography

Bouissac, Paul. Introduction: A Challenge for Semiotics. Semiotica 100 (2-4): 99-108. 1994.

Breuil, Henri. Four Hundred Centuries of Cave Art. Montignac: Centre d'Etudes et de Documentation Prehistoriques. 1952.

Durkheim, Emile. Rules of Sociological Method. New York: Simon and Schuster. 1982.

Fraser, Douglas and Herbert M. Cole, eds. Introduction to African Art and Leadership. Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press. 2004.

Gombrich, Ernst Hans. Art and Illusion: A Study in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation. London: Pantheon Books. 1960.

Graziosi, Paolo. Paleolithic Art. London: Faber & Faber. 1960.

Harley, George. Masks as Agents of Social Control in Northeast Liberia. Cambridge: Peabody Museum. 1971.

Hatcher, Evelyn Payne. Visual Metaphors: A Formal Analysis of Navajo Art. New York: West Publishing Company. 1974.

Hauser, Arnold. The Social History of Art vol. 1. London: The Estate of Arnold Hauser. 1962.

Jameson, Fredric. The Political Unconscious. New York: Cornell University Press. 1981.

Leroi-Gourhan, André. The Dawn of European Art: An Introduction to Palaeolithic Cave Painting. New York: Cambridge University Press. 1982.

— Treasures of Prehistoric Art. Trans. N. Guterman. New York: Harry N. Abrams. 1967.

Lévi-Strauss, Claude. Structural Anthropology. New York: Doubleday Anchor Books. 1963.

— Tristes Tropiques. New York: Criterion Books. 1974.

Lukács, Georg. History and Class Consciousness: Studies in Marxist Dialectics. Trans. Rodney Livingstone. Massachusetts: The MIT Press. 1971.

Mitra, Panchanan. Prehistoric India: Its Place in the World's Cultures. Calcutta: University of Calcutta. 1927.

Nadin, Mihai. Understanding prehistoric images in the post-historic age: A cognitive project. emiotica 100 (2-4): 387-404. 1994.

Paul, Robert. The Sherpa Temple as a Model of Psyche. American Ethnologist 3 (1): 131-146. 1976.

Radcliffe-Brown, Alfred. The Andaman Islanders. New York: Free Press. 1964.

— Structure and Function in Primitive Society: Essays and Addresses. New York: Free Press. 1965.

Sankalia, H.D. Pre-historic art in India. New Delhi: Vikas Publishing. 1978.

Soneasson, Goran. Prolegomena to the Semiotic Analysis of prehistoric Visual Displays. Semiotica 100 (2-4): 267-331. 1994.

Temple, Richard Carnac, ed. The Indian Antiquary XXX. 1901.

Ucko, Peter J., and Andrée Rosenfeld. Palaeolithic cave art. London: McGraw-Hill. 1967.