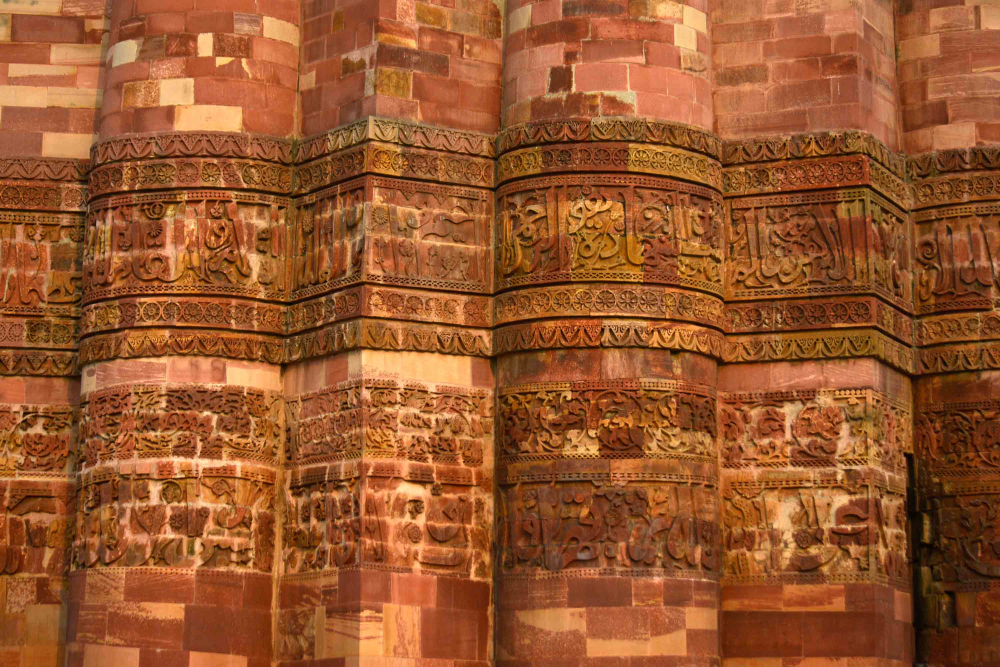

We look at the Qutub complex, which presents an amalgamation of several architectural styles in India—Persian, Arabic and Indian—that later came to be known as Indo-Saracenic. The famed Qutub Minar itself has braved natural calamities and disastrous preservation efforts to continue as one of India’s most identifiable monuments. (Photo courtesy: Ayan Ghosh/Sahapedia)

There are several reasons why the 72.5-metre-high Qutub Minar has come to be known as Delhi’s enduring symbol. It is the world’s tallest brick tower and one of the finest specimens of Islamic craftsmanship as well. Situated in a lush green complex of monuments and ruins in the Mehrauli Archaeological Park, formerly called Qila Rai Pithora, this UNESCO World Heritage Site attracts around three million visitors annually. Indeed, very much like the city it symbolises, the Qutub Minar has not only stood the test of time for over 800 years but also weathered several design changes, repairs and reconstructions, lightning and earthquakes—even preservation efforts.

Related | The Qutb Complex: An Overview

The Qutub Minar is a five-storeyed red sandstone tower built by Muslim conquerors in the thirteenth century to commemorate their final triumph over the Rajput rulers of Delhi, while also serving as a tower from where muezzins (criers) call for prayer at the Quwwatu'l-Islam mosque nearby. The minar (tower) is engraved with fine arabesque decorations on its surface, mainly verses from the Quran. Although reportedly based on the Minaret of Jam in Ghazni, western Afghanistan, Qutub Minar is far larger and more richly engraved with looped bells and garlands and lotus borders. Ibn Battuta, the famous fourteenth-century Moroccan traveller, a judge during the time of Mohammed Bin Tughlaq and a caretaker of the complex for a while, was awed by ‘. . . the minaret, which has no parallel in the lands of Islam’.[1]

A Layered History

The story of Qutub Minar is as diverse and layered as India’s history and culture. The Qutub complex, which also houses the Alai Darwaza, Quwwatu'l-Islam mosque and the Iron pillar, showcases the coexistence of the architectural heritage and styles of various faiths—sometimes a harmonious blend and a hasty juxtaposition at others. The construction of the minar was started in 1198 BCE by Qutubu’d-din Aibak, the mamluk (slave) commander-in-chief of Muhammad of Ghori, and founder of Muslim rule in India. Aibak, who became the first king of the Mamluk dynasty, managed to complete just the base of the tower before his death in 1211. His son-in-law and successor, Shamsu’d-din Iltutmish (1211–36), added three more storeys. When the minar was damaged by lightning in the fourteenth century, Firoz Shah Tughlaq (1351–88) constructed the topmost part, a fine specimen of workmanship in white marble and red sandstone.

Also read | The Qutb Complex and the Arcuate System of Construction in India

Aibak’s rule, architect Richa Bansal Aggarwal writes in Sahapedia, marked the beginning of the Delhi Sultanate (1192–1526), which had great influence on the subcontinent’s culture, faith, art and architecture.[2] Indeed, the complex presents several stunning examples of a new era of architecture in India, an amalgamation of Persian, Arabic and Indian styles that later came to be known as Indo-Saracenic, alternatively Indo-Islamic. The mix happened naturally as the complex was built on the ruins of Lal Kot that had 27 Hindu and Jain temples, a fact the builders themselves inscribed on the monuments. Inscriptions in Persian-Arabic and Nagari characters on the minar tell the complete story—the why, who and how of the minar, the time taken, and many other details.

According to one inscription in Kufic language, the minar is said to have been established to reflect the shadow of God in the East and West. This is particularly evident in the adjoining Quwwatu’l-Islam mosque, the first of its kind in Delhi. Its construction was started under Aibak in 1192-93. The mosque has pillars that seem to have been used unchanged from the earlier temple, as well as carved columns and corbelled domes made of dressed stone, giving it a feel of a Hindu/Jain temple.

The magnificent Alai Darwaza, added to the complex in 1311, is the earliest-known example of a true Mughal arch, with hollow minarets and a unique dome housing a small cupola on top of the larger one. The gateway, built of red sandstone and white marble, is extensively decorated with jaali (lattice-screen) patterns, and geometric and floral designs. Alauddin Khilji’s madrasa and tomb that are mostly in ruins, Iltutmish’s calligraphy-decorated sandstone and marble mausoleum of Saracenic style, with geometric patterns and inscriptions, are other brilliant specimens of the architecture in the complex. The most outstanding of them all is entirely Hindu; this is a 7-metre-high iron pillar, built in the fourth century CE as a Vishnudhvaja (god Vishnu’s tower) on the hill of Vishnupada, carrying an image of the Hindu god Garuda on top.[3] The pillar is made of 98 per cent iron but has still not rusted. It is widely believed that the pillar’s inscriptions about being created in memory of king Chandra refer to Chandragupta Maurya the second, which dates the pillar to 375–415 CE, highlighting India’s astonishing achievements in metallurgy some 1,600 years ago.

Also see | Qutb Complex

Experts say that the Qutub Minar—indeed the entire complex in general—also marks a departure in the finer points of architecture as it depicts a clear shift from the trabeate (beams, pillars and lintels) form to arcuate (true structural arches, a style that originated in Rome), showing how well the indigenous craftspeople adapted to new building styles.[4] One of the engravings on the minar says Shri Vishwakarma prasade rachita (created with the blessings of Vishwakarma, the Hindu god of construction), reflecting the contribution of the local craftspeople.

Weathered, but not beaten

The Qutub Minar, which tapers out from 14.32 metres at its base to 2.75 metres at the top, has a balcony surrounding each storey, supported by stone brackets decorated in a honeycomb design. Earlier, one could climb the 379-step spiral staircase to the very top, but a tragic stampede in 1981 led to its permanent closure. Even the iron pillar, which visitors used to encircle with their hands for good luck, is enclosed within a barrier due to human contact corroding its surface.

Indeed, the environmental threat to the monuments in the complex is quite serious. It has been damaged several times by natural disasters. Apart from two lightning strikes in 1368 and 1503, an earthquake in 1802 toppled the cupola. The minar tilts just over 65 cm from the vertical, which the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) considers safe; it also feels that the strong base of the minar precludes any extensive damage owing to human-made factors. But rainwater seepage continues to be a threat. Haphazard and hasty construction, types of materials used, faulty repairs by the British, seismic threats that make the topmost storeys vulnerable, and historical importance—all these factors make Qutub Minar prime on ASI’s preservation list.

Did You Know?

- Some 358 lights are used to bathe the Qutub Minar complex and its main monuments in light for four hours from 7–11 pm every day.

- In 1828, during repairs to the Qutub Minar, a pillared red sandstone cupola was added. Everyone found it ugly, so Lord Hardinge ordered its removal in 1848. Known as Smith’s folly, it now lies on a lawn south-east of the minar.

- The Qutub Festival of Indian classical music and dance takes place here every November-December.

- According to travel historian Ibn Battuta, even elephants could go up the Qutub Minar passage. He wrote, ‘A person in whom I have confidence told me that when it was built he saw an elephant climbing with stones to the top.’[5]

This article was also published on The Indian Express.

Notes

[1] Medha Saxena, ‘Ibn Battuta and His Times,’The Wire, July 2, 2017, accessed November 9, 2019, https://thewire.in/history/ibn-battuta-and-his-times.

[2] Richa Bansal Agarwal, ‘The Qutub Complex and the Arcuate System of Construction in India,’ Sahapedia.org, June 9, 2017, accessed November 9, 2019, https://www.sahapedia.org/the-Qutub-complex-and-the-arcuate-system-of-construction-india.

[3] Lucy Peck, ‘The Qutub Complex: An Overview,’ Sahapedia.org, June 9, 2017, accessed November 9, 2019, https://www.sahapedia.org/the-Qutub-complex-overview.

[4] Richa Bansal Agarwal, ‘The Qutub Complex and the Arcuate System of Construction in India,’ Sahapedia.org, June 9, 2017, accessed November 9, 2019, https://www.sahapedia.org/the-Qutub-complex-and-the-arcuate-system-of-construction-india.

[5] Medha Saxena, ‘Ibn Battuta and His Times,’ The Wire, July 2, 2017, accessed November 9, 2019, https://thewire.in/history/ibn-battuta-and-his-times.