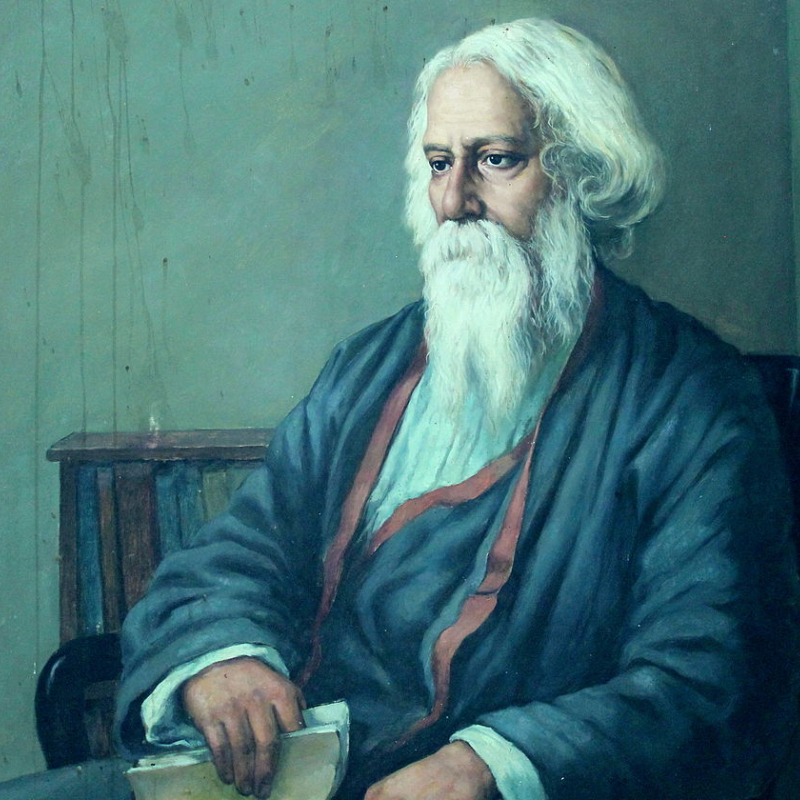

As with many progressive Hindus of the time, Rabindranath Tagore had some conflicting ideas about the role of women in marriage and marital life. We look at how Tagore underwent brief but visible phases of social and cultural conservatism. (Photo Source: Cherishsantosh/Wikimedia Commons) [i]

In a hilarious poem composed in 1888—‘Nabadampatir Premalap’ (Romantic Exchanges Between Newlyweds)—Rabindranath Tagore describes an educated husband enthusiastically but vainly reciting romantic verses before his newly wedded child-bride who kept playing with her dolls! Such incongruities in a young Hindu couple and the problems arising therefrom were issues that agitated the Hindu intelligentsia in colonial Bengal. We are only too aware of the public debates that occurred around the issues of Sati, widow remarriages, female education, polygamy and zenana seclusion. But this conceals the fact that woman-related reforms were often deeply interpersonal, limited to only members of the family.

That year, Tagore also authored another poem titled ‘Parityakta’ (The Deserted), where he bemoaned the way in which educated Hindus of his time were visibly retreating from the progressive social vision that had once beckoned them. Only about a year earlier, the poet had been drawn into controversy with a literary critic by the name of Chandranath Basu, who, by the 1880s, had emerged as a publicist for traditional Hinduism.

Also Read | Tagore and Caste: Brahmacharyasram to Swadeshi Movement

Tagore felt that early marriages were useful only when kinship ties had the strength to resist fragmentation and the birth of nuclear families (Photo Source: Wikimedia Commons)

In 1887, Tagore reacted to two successive essays by Basu titled Hindu Vivaha (Hindu Marriage) and Hindu Vivaher Boyos O Uddesha (The Ideal Age for Marriage Among Hindus and its Aim). In these essays, Basu had argued that Hindu marriages were essentially characterised by their ‘purity’ and ‘spirituality’, a claim that he then tried to posit against the allegedly ‘materialistic’ nature of love, marriage and conjugal relationships in Western societies. His claim also was that Hindus had traditionally held their women in high social esteem. While Christianity had made the woman the man’s equal, the Hindus had made her his god. Where women were so venerated, Basu was to argue, even the gods rejoiced!

Tagore’s critique of Basu rested on two related arguments: first, the failure to take a more historicist-evolutionary view of the Hindus as a community and their institution of marriage itself and, second, the specious argument that Hindus had unequivocally respected their women. First, contemporary Hindu marriages could not possibly follow the norms or practices laid down by early law-givers like Manu and Raghunandan. Second, contrary to Basu’s claims, the Hindu woman’s salvation was seen to lie in serving her husband. In substance, Tagore’s argument was that Hindu marriages, as with every other marriage, arose in certain social and individual needs, such as securing a progeny and a functional family life. That Tagore took the threat posed by Basu’s arguments seriously is evident from the fact that the debate between the two lasted another eight years, acquiring new dimensions in the process.

An 1883 photograph of a young Tagore with his wife, Mrinalini Devi, who was 12 years younger to him (Photo Source: Wikimedia Commons)

The Conservatism of Tagore

Ironically, it was at this point that Tagore also begins to reveal some conservatism. While he disagreed with the conservative argument that Hinduism did not confer equal rights upon men and women, he also defended such inequity on the grounds of social expediency. If, reportedly, raising children and maintaining family life were the critical social needs attached to marriages, the wife’s fidelity to a husband was socially more important than the husband’s to his wife. In Tagore’s understanding, this justified the remarriage of the widowed male more than that of the female widow. Every time a widow remarried, the children born of the first marriage had either to undergo transference of lineage or else to go motherless, and both these eventualities, allegedly, were socially unsettling. Quite inexplicably, Tagore stuck to the same argument even in the case of childless widows.

The conservative opposition accused Tagore of following double standards; it was observed how he had married a 10-year-old girl at a time when his own age was twice as much as that of his child bride.[ii] Patriotic impulse also moved Tagore to strongly oppose social legislation, arguing that Indians had to set their own house in order rather than abrogate that right to an alien race and government. Such postures explain why, by the close of the 19th century, the demand for political reform overtook that concerning the social.

Also Read | Tagore on Nationalism: In Conversation with Prof. Ashis Nandy

Rightly or wrongly, Tagore associated the practice of early marriage or betrothals with the institution of extended families; However, he also hoped that the gradual weakening of extended families would seriously discourage early marriages: nuclear households could be run by mature men and women alone. He might have added, though, that reform work itself was gradually altering the Hindu social organisation. Presumably, many educated men had to set up independent households after their parents refused to accept the idea of an educated Hindu bride, the blatant disregard for commensalities built around caste, aiding widow remarriages or ritual transgressions resulting from a change of religious faith or travel to ‘mleccha’ (barbaric) lands.

In his literary as well as personal life, Rabindranath Tagore did undergo brief but visible phases of social and cultural conservatism. That notwithstanding, he and his work represented the progressive face of man–woman relationships that was to develop in modern Bengal. For Tagore, importantly, human love was but a metaphor for the love of the divine and that helped him to poetically express and enhance the sense of equity and social justice between the sexes.

This article was also published on The Indian Express.

[i] This article is based upon Rabindranath Tagore’s rejoinder to Chandranath Basu, first presented as a paper read at the Science Association Hall, 1887, and subsequently published in the Bengali journal Bharati O Balak, Bhadra-Aswin, 1294 BS (August–September, 1887). Excerpts from this paper are available in English translation in Social and Religious Reform: The Hindus of British India (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2003), 156–61.

[ii] Letter by one ‘Bharadwaj’ titled ‘Rabibabu O Balya Vibaha’ (Rabindranath and Child Marriages), Bibha: Chaitra, 1294 BS (March–April 1888).