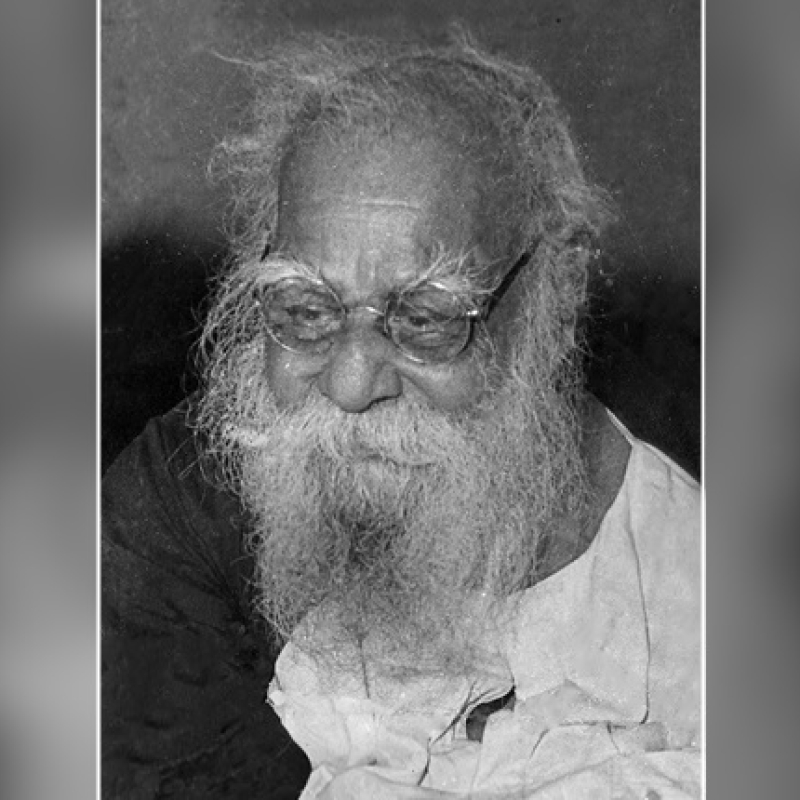

E.V. Ramasamy, popularly addressed as Periyar or ‘the Great One’, laid the ideological foundations of modern Tamil politics and social life. More than a century after he championed equal rights for low-caste communities and women, we take stock of his popular, but complex, legacy. (Photo courtesy: Wikimedia Commons)

A rationalist Dravidian social reformer of the twentieth century, E.V. Ramasamy, popularly addressed as ‘Periyar’ or ‘the Great One’, was born on September 17, 1879. Even a century after he argued in favour of equal rights for lower-caste communities and women, issues of ‘caste identities’ and its politics continue to be as relevant. This is especially true in the case of his home state, Tamil Nadu, which beckons us to study the popular yet complex legacy he has left behind.

All the major political and social organisations in Tamil Nadu have either roots in the sociopolitical movement Periyar led from the early decades of the twentieth century or engaged with his thought at different points in their existence. It would be safe to say that he laid the ideological foundations of modern Tamil politics and social life. Periyar founded the Self-Respect Movement in 1925, after a brief stint with the Indian National Congress and Mahatma Gandhi. This movement went on to become the cornerstone of the vibrant anti-caste, non-Brahmin social movement the region was to witness in the decades to follow.

In an obituary for Periyar, published right after his death in December 1973 in the Economic and Political Weekly, his contributions have been identified manifold. He carried out the most vigorous attack against traditionalism of all kinds, prevalent in the society, and along the axes of caste and religion in particular.[1] This attack was based on the inherent irrationality of these age-old systems and Periyar never let one opportunity pass to expose the inconsistencies and blind spots in the material and ideological structures of caste and religion.

Related | In conversation with Prof. Vijaya Ramaswamy on Kamba-ramayaṇam

Periyar and the ‘Women’s Question’

Apart from the well-known aspects of his political movement, an emphasis on his radical and visionary approach to the ‘women’s question’—as it was termed during the later years of anticolonial movement—is important. Periyar consistently argued for equal rights of women in marriage, inheritance of property and civic life in general. He vehemently argued for accessible contraceptive methods for women, as early as in the 1930s. He redesigned marriage ceremonies, which came to be known as ‘self-respect marriages’, without any religious or community customs and without a priest. Feminist scholars have argued how this reconfiguration of the marriage ceremony led to the ‘desacralisation of marriages’ making them into modern contracts that individuals enter into with knowledge and consent. Even more radically, he contended that ‘no odium should be placed on a married woman who desires men other than her husband’.[2] In short, he pushed the sociocultural potential of modernity to secure freedom, rights and dignity, not just for the lower-caste communities, but also women.

His major contribution to the modern social thought of India is possibly the emphasis on the idea of dialogue. He insisted that each individual must think for herself, enter into dialogues with each other and rationally carry out the process of decision-making. Ancient Greek philosopher Socrates was his ideal in this regard, and Periyar stressed on the importance of forming and maintaining public platforms for such discussions. Dravidar Kazhagam (DK)—the political outfit he founded in 1944 (it was known as the Justice Party until then)—worked for the ‘Adi-Dravida people’, who he thought were oppressed by the pro-Hindi nationalists, politically, and by the Brahmins, socioculturally. DK underwent several splinters in the later years and major political parties, including the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) and All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIDMK), claim legacy of the movement.

Also see | Tagore and Caste: From Brahmacharyasram to Swadeshi Movement (1901–07)

Periyar and Gandhi

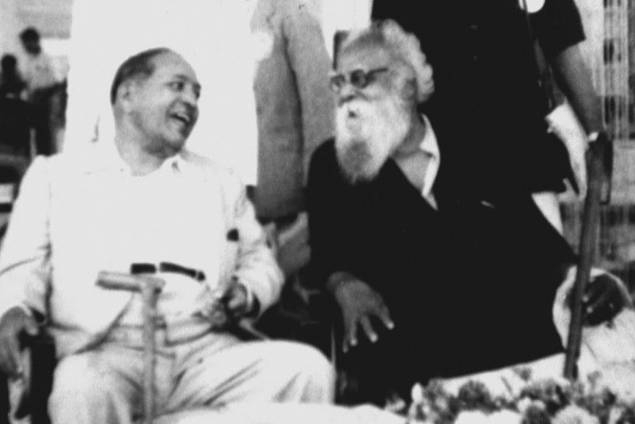

Periyar was a prolific writer and orator, who could communicate with all sections of the society effectively. Even when there were numerous ideological differences between Periyar and Gandhi, the way both of them communicated to ordinary masses made them great leaders. In the beginning, Periyar was attracted to the Gandhian ideals of noncooperation and constructive work, though later he differed deeply with Gandhi on both political and intellectual levels. His differences with Gandhi and mainstream nationalist movement represented by Indian National Congress grew sharper along the lines of the method to be adopted the freedom struggle and conceptualisation of freedom itself. He has argued that nationalism will make sense only when ‘a nation’s citizens could realise their ideal, without having to forgo or compromise on their dignity’. [3] His complex idea of the free nation included ideals such as ‘an all-round growth of knowledge, spread of education, the cultivation of rational thought, work, industry, equality, unity, initiative and honesty and the abolition of poverty, injustice and untouchability,’ writes feminist scholar V. Geetha.[4] In that sense, it is safe to assume that Periyar’s anticolonial political imagination was more substantive than rhetorical, when it came to questions of caste, gender and region.

Also read | Caste, Region and History: Mahisyas and the ‘Anti-Partition’ Mobilisation in 1932

Mapping his political and social legacy inspires us not only to revisit the diverse strands of history available to us as a people, but also to defend the free and rational stream in our political and social consciousness. His words and the self-respect movement have much to offer us in the current scenario of narrowing spaces of dissent and debate, as well as shrinking avenues of free thought.

This article was also published on The Indian Express.

Notes

[1] Correspondent, ‘TAMIL NADU-Passing of the Periyar,’ Economic and Political Weekly, 9, no. 1–2, (January 1974): 13–15, accessed November 22, 2019, https://www.epw.in/journal/1974/1-26/our-correspondent-columns/tamil-nadu-passing-periyar.html.

[2] S. Anandhi, ‘Sex and Sensibility in Tamil Politics’, Economic and Political Weekly, 40, no. 47 (November 2005): 48–76, accessed November 22, 2019, https://www.epw.in/journal/2005/47/commentary/sex-and-sensibility-tamil-politics.html.

[3] V. Geetha, ‘Who Is the Third that Walks Behind You?,’ Economic and Political Weekly, 36, no. 2 (January 2001): 163, accessed November 22, 2019, https://www.epw.in/journal/2001/02/discussion/who-third-walks-behind-you.html.

[4] Ibid.