Indian Christianity is as old as the apostolic times. It is said to be the fruition of the acts of St. Thomas, the holy apostle who preached in Kerala. Very little is known about the history of St. Thomas Christians, especially in their early phases. It is built upon certain oral and literary traditions. With regard to most cultures, art and architecture often serve as important sources of history. But in case of the history of the St. Thomas Christians that was never the case. The community itself relied mostly on oral traditions for the early history, where no other sources were available, and certain literary sources for defining their history of the later periods.

It is very hard to assume how or what was the artistic and architectural tradition of St. Thomas Christians, at least until the coming of the Portuguese. The use of building materials, which were not so durable in the weather conditions specific to the region, also might be a reason for the absence of any remains for posterity. During the Portuguese colonial period and even afterwards, old churches were demolished to build new ones. In view of providing more space and for conforming to newer architectural styles, even today this process is continued.

Traditions of art and architecture in the early phase

Literary sources available from the travellers to the Indian coast testify to a formidable Christian presence much before the Portuguese stepped on this soil. The churches of that period shared the indigenous architectural features and there was no distinction between them and the temples, except for a cross on top of the church. Most of the travellers’ accounts state that there were only crosses in the churches, positioned in a most venerable fashion. Some also note the presence murals in these churches.

Fig. 1. Pahlavi-inscribed St. Thomas crosses: St. Mary’s Knanite Jacobite Valiyapally, Kottayam (left) and St. George Church, Kadamattam (right) (Photo: Antony Joseph Nangelimalil)

A few artefacts such as St. Thomas crosses and baptismal fonts survive to this day. They were made by carving granite, which is very durable. St. Thomas crosses (Mar Thoma Sleeva), which date back at least to the 9th century, were discovered from several sites in Kerala in later periods. The presence of such crosses in Mylapore near Chennai in Tamil Nadu (where there is the tomb of Apostle St. Thomas), Agasim in Goa and Anuradhapura in Sri Lanka attests to the extensive presence of early Christian communities in those regions. Many of the granite baptismal fonts which continue to be in use in many of the churches of the early Christian communities, do not bear any influence of the colonial times, demonstrating how the Christians adopted indigenous sculptural traditions in the creation of their art before the Portuguese intervened. There are also a few other architectural elements such as open-air granite crosses which trace their allegiance to the indigenous traditions of the land.

Fig. 2. Simhavyala carrying the baptismal font, made of granite, St. Mary’s Church, Kanjoor (Photo: Antony Joseph Nangelimalil)

The colonial period and its impact on St. Thomas Christian art

The arrival of Vasco da Gama and his fleet in 1498 in Cranganore, Malabar Coast, marked the beginning of a new era in Indian history. This event eventually led to the process of the colonisation of India, leaving indelible marks on the face of the country. However, this event drastically changed the course of history of a specific community of Malabar, the St. Thomas Christians, i.e. the native Christian community. They were forcefully severed both from their age-old relation to the bishops of the East Syrian Church and long-lived tradition and practices by the Portuguese Padroado administration. Bishops from Syria were no more allowed on Malabar soil after the demise of the last East Syrian Archbishop, Mar Abraham, in 1597. Since then the history of St. Thomas Christians became too turbulent, eventually leading to the division of the St. Thomas Christian community.

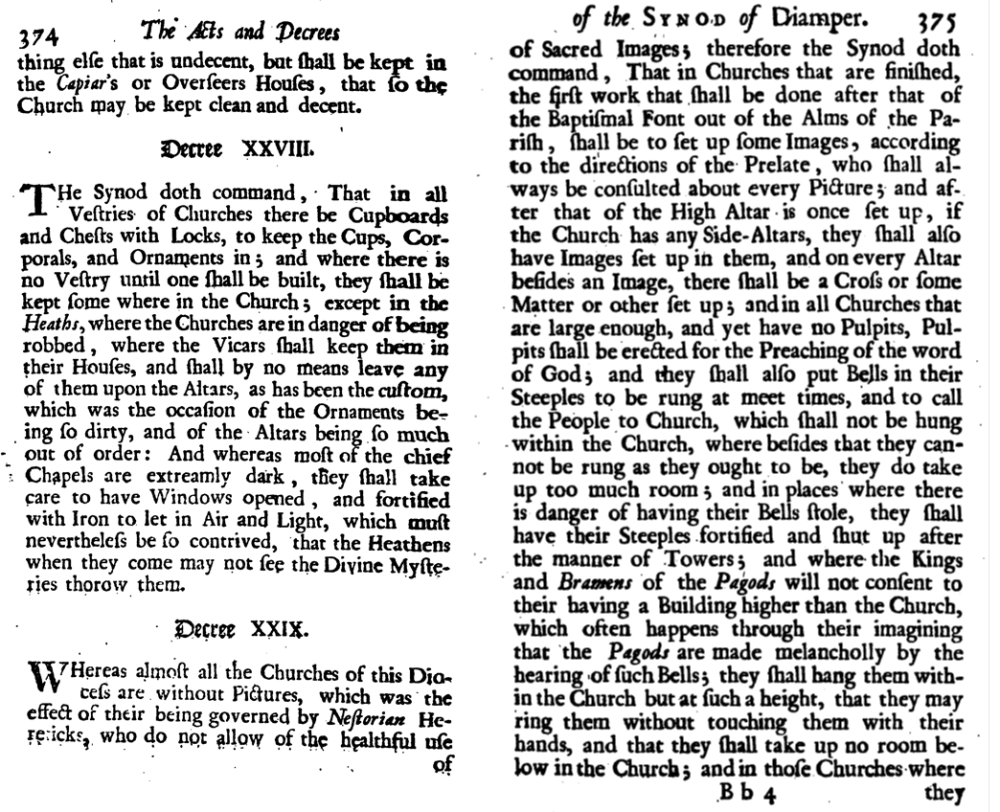

The Synod of Diamper, convened illegitimately in 1599 by the Portuguese Archbishop of Goa, Dom Alexis Menezes, using political pressure and military coercion, enforced the Padroado rule over the St. Thomas Christians. Though the Synodal acts adversely affected the continuity of the long-lived traditions of the native Christians, it set a new direction in their life and practices. One of the most important impacts it made was on their architectural and artistic practices.

Fig. 3. Pages 374 and 375 of the first English translation of the Acts and Decrees of Synod of Diamper (1599) printed in 1694 in England

The old churches were demolished and new ones built. The ground plan of the churches was significantly altered in order to accommodate the practices newly established by canons of the Synod of Diamper. Inspired by the Catholic spirit stimulated by the Council of Trent, the decrees were enacted to set up images or icons in the church, which was a practice unfamiliar to St. Thomas Christian Churches until that period:

Whereas almost all the churches of this Diocese are without pictures, which was the effect of their being Nestorian Hereticks, who do not allow of the healthful use of Sacred Images; therefore the Synod doth command, That in Churches that are finished, the first work that shall be done after that of the Baptismal Font out of the Alms of the Parish, shall be to set up some images, according to the direction of the Prelate, who shall always be consulted about every picture; and after that of High Altar is once set up, if the Church has any Side-Altars, they shall also have images set up in them, and on every Altar besides an Image, there shall be a Cross or some matter or other set up; and in all Churches that are large enough, and yet have no Pulpits, Pulpits shall be erected for the preaching of the word of God; … (Geddes, 1694, pp. 374-375).

Decree XXIX of Act VIII titled ‘Of the Reformation of the Church Affairs’ became the driving force for the introduction of a new style in altar adornment. The retable tradition, which has a long and established history in the West, was presented in the churches of Kerala and the St. Thomas Christians soon accepted it. By the end of 19th century, elaborate mannerist retables became a very important aspect of church architecture and an artistic expression of St. Thomas Christian pride.

Retable: Meaning and definition

The term retable comes from Latin. The root terms retro and tabula combine to form retrotabulum in Medieval Latin. Retro means backward, back or behind. Tabula generally means table, but a more original meaning would be ‘that which stands’. Retrotabulum was retablo in Spanish and rétable in French. Hence, retable etymologically means ‘that which stands behind’. Our definition of retable adds to this meaning, its function in a given architectural context, i.e., ‘that which stands behind the altar’, extending above it as an adornment to it. They are also known as altarpieces on account of their functions. The coinage ‘altarpiece’ includes both retables and the simple painted altarpieces which are movable. Retable is more specific in comparison to altarpiece in that sense. Retables are generally fixed structures which are not movable and more architectonic in its form.

The retables in St. Thomas Christian churches

There are three kinds of retables generally found in Kerala’s churches based on the materials used to compose them. There are mural retables, wooden retables, and stucco retables.

The mural retables are murals on the principal wall of the sanctuary towards which the worshippers face during the liturgy. They were not conceived as murals but as retables, i.e., those murals were not decorative in purpose, rather they were conceived as actual retables painted on to the wall following actual models or its risco, i.e., draft drawings. The mural retables could be the earliest retable forms that appeared in Kerala’s churches. It was easier for the Christian missionaries to get a painting done on the wall rather than erecting an actual retable, as there was an active tradition of mural painting in Kerala’s temples during the same period. The same techniques were employed in decorating the sanctuary of the churches with mural retables. However, it is interesting to note that neither did the temple mural style come into the churches nor did the Christian mural style make it to the walls of temples, despite the fact that both these mural traditions existed in the same land at the same time.

The mural retables are still visible and better preserved in many churches, whereas they have been covered up or even destroyed by the later addition of actual retables in several others. Again, many of them have been lost in the process of reconstruction and renovation of the churches. Since the artists attempted to render the retables in a naturalistic way as far as possible, we can make out the different formats of retables they created on the walls of the sanctuary, which we will see in the later discussions.

Fig. 4. Mural retable, St. Sebastian’s Karottupally, Muttuchira (Photo: Antony Joseph Nangelimalil)

Being a tropical rainforest region, timber was available in plenty in the state. There were also highly skilled carpenters and wood carvers as is evident from the architecture and sculptures we see in the temples. Many of the churches in Kerala, therefore, erected retables made of wood. The idea of retables that was achieved in murals as two-dimensional designs were later actualised three-dimensionally in wood. The retables made of wood were painted and gilded with gold foils as well.

Fig. 5. Uni-panelled high altar retable, Artist: Luka Peeli, 1911, St. George Old Church, Edappally (Photo: Antony Joseph Nangelimalil)

St. Thomas Christian churches followed the mannerist matrix of retable which was brought by the European missionaries. In certain cases, there exists a claim that the retable itself was imported from Europe by the missionaries. Starting with simple elementary forms, it gradually evolved to larger and complex formats in the later phases of its development.

Fig. 6. Multi-panelled retable on high altar, wood, Mar Sleeva Church, Pazhavangady, Alappuzha (Photo: Antony Joseph Nangelimalil)

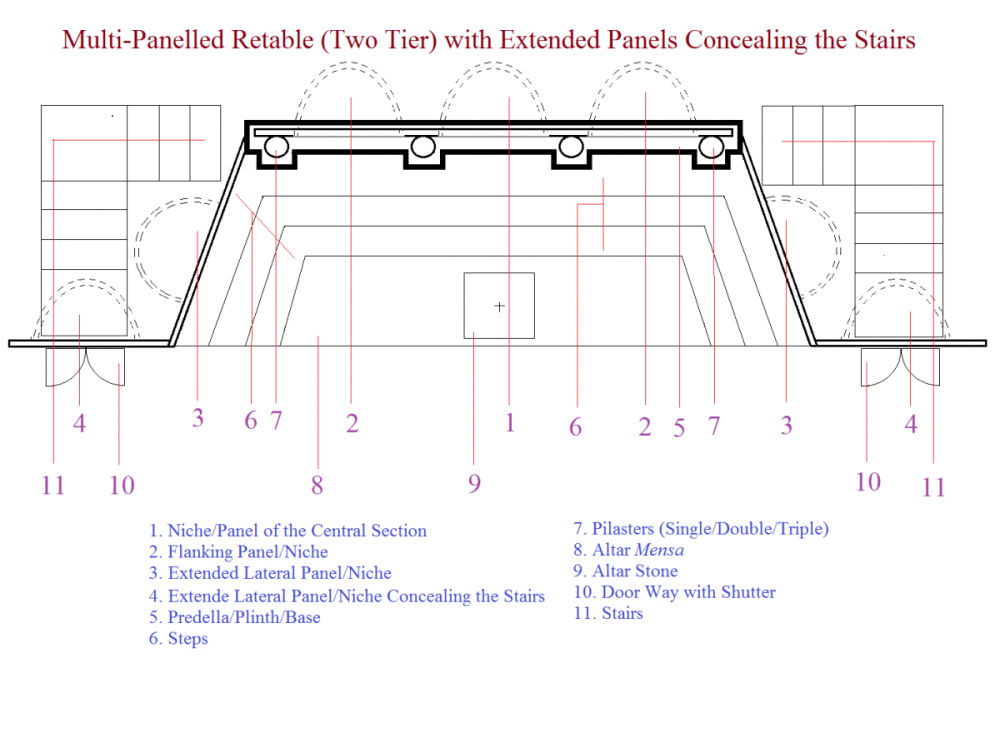

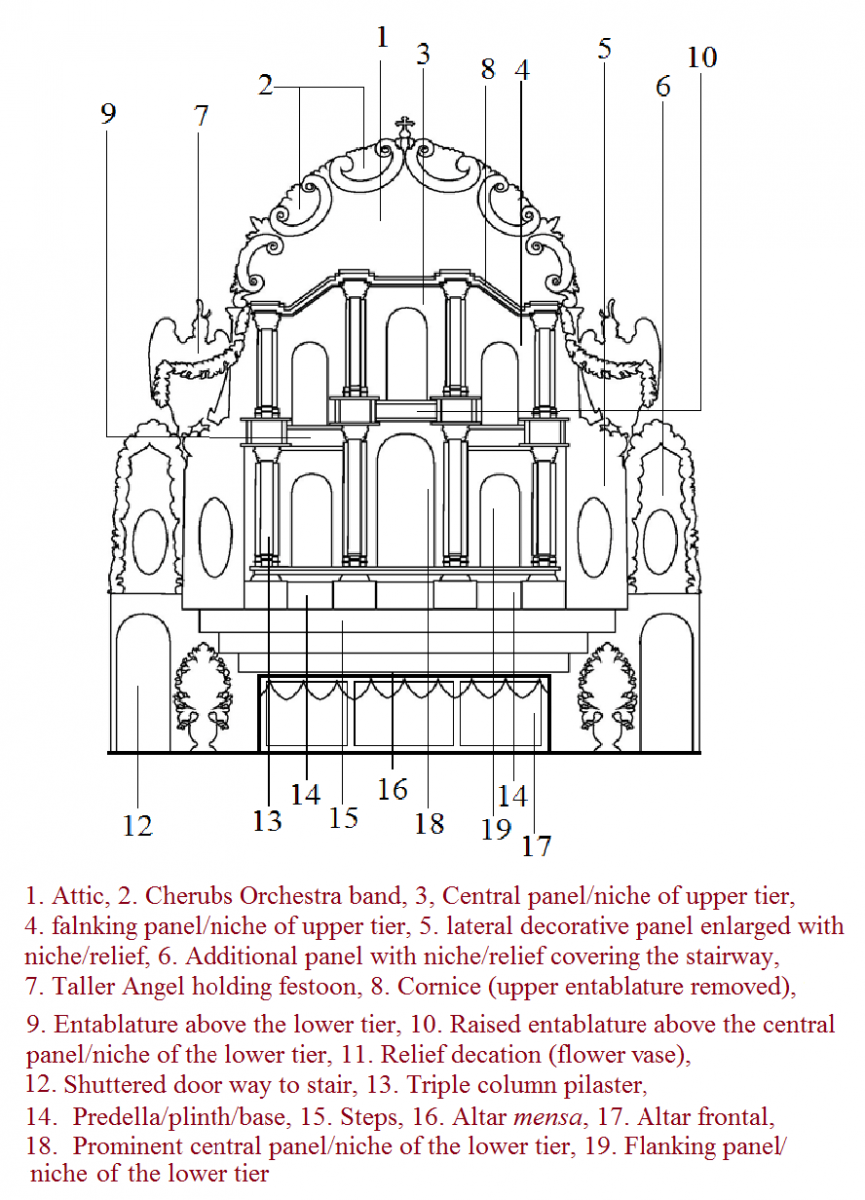

The retable structures in Kerala are usually found fixed along with the altar, where the Eucharistic Mass is offered. The mensa of the altar is placed above the altar frontal. From the rear end of the mensa, stems the retable. The predella or plinth which supports the whole structure is supported at the rear end of the altar. On the predella stands a panel with painting supported by two frames mostly in the form of pilasters on both sides. An entablature runs horizontally over the panel from the capital of one pilaster to the other. The whole structure is surmounted by an attic usually in semi-circular shape, fixed over the entablature. This is the description of the most elementary form of retable, with a single panel. The retables were further evolved and enlarged to suit the needs of the church architecture which progressed over time. Single- or double-tiered templates, divided as well as bordered by four vertical pilasters, form separate panels. The number of panels is found to be one, three or six. The retables are expanded by adding lateral decorative panels on both sides and futher expanded by adding decorative panels which form the wings of the retable.

As the size of the retable structure expanded vertically and laterally, each of the individual elements also evolved to make the whole ensemble more decorative and elegant. The single pilasters were first doubled and then tripled. The now fluted pilasters were adorned with motifs of spiralling vines, floral, faunal or anthropomorphic or a mixture of some of these. The attics which crowned the retable are usually found in different forms. All these forms evolved along with the evolution of the retable. Acanthus motif and opening scroll motif are two important attic types which adorned the retables. The entablature, the lateral decorative panels, the predella or plinth, the steps, altar mensa, altar frontal, and the panel niches and their arches, all of them significantly evolved over time. This evolution is perceptible from the retables of successive periods.

Fig. 7. Section of multi-panelled retable (two tiers) with extend panels/niches concealing stairs (Illustration: Antony Joseph Nangelimalil)

On the wooden retables we also find different panel types. They are two-dimensional painted panels, bas-relief panels carved on wood and panels housing three-dimensional round sculptures in deep niches. Each of these panel types is found as exclusively used on some retables, and they are compositely used on some other retables keeping the perfect symmetry of the retable ensemble.

Fig. 8. Elements of multi-panelled (two-tiered) retable with extended panels covering the stairway (Illustration: Chandni Guha Roy)

Retables were also executed in stucco medium, which was used as a popular building material. The stucco retables attained its form through masonry work with lime mortar and laterite. Once the form was created, they were plastered with stucco and adorned with sundry decorative elements. Then they were painted and gilded. Since the basic form is built with laterite and lime mortar, which was the regular building material with which the walls were built, the stucco retables structurally swelled up from the wall to which they were attached. So, they appeared to be the relief of a retable structure especially with those of mannerist format. The change of medium significantly affected the form of the retable and forms of embellishing elements.

Wooden retables appear to be more popular over the stucco retables, especially in the making of mannerist retables. A good number of the stucco retables found today are neo-Gothic retables which became a fashion in the early half of the 20th century. This is mainly because of the limitation of stucco as a medium in executing the designs of mannerist retables. The intricate designs and the self-standing elements which we see in the wooden retables can hardly be achieved in stucco with similar ease.

A brief note on the iconography of St. Thomas Christian retables

It is necessary to look into how the retable, which is a house of icons, engages with the worshipping community. Each icon housed in the retables reveals itself or the person it represents in the context of their earthly or divine life, which is significant to Christian faith. The retable artists borrowed techniques from the artistic tradition of Europe to represent divine imagery. The representations of icons on retables in St. Thomas Christian churches borrow from the European art tradition rather than Indian visual tradition. The Trinitarian Godhead—the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost—mostly dominated the iconography of the retables. The mysteries of incarnation of Christ become an important theme of representation along with Mother Mary in many a retable. Other saints and their lives are also represented with due importance. Various Biblical personalities and themes also appear in many retables. The retables found in Kerala focus mainly on two kinds of representation on its panels: narrative and iconic. Other than these, there are allegorical and decorative representations too.

Conclusion

The cross seemed to be the only popular icon among St. Thomas Christians until the 15th century. It was during the Portuguese colonial period that icons and images were introduced among the native Christians. Following the canons of the Council of Trent, the Synod of Diamper pronounced decrees to enforce the use and veneration of icons in the churches. Therefore, it may be said that though Christianity was present in Malabar, there was a vacuum as far as visual art practices in the religious community is concerned, except for a few indigenous elements mentioned at the beginning. It was to this vacuum that the European idiom of Christian art was introduced, which was embraced wholeheartedly by the Catholic fraction of the St. Thomas Christians who constitute the Syro-Malabar Church today. Even the defected fractions (non-Catholic) of St. Thomas Christians accepted this new art tradition in varying degrees.

References

Geddes, Michael. 1694. The History of the Church of Malabar, Together with the Synod of Diamper. London: Sam. Smith and Benj. Walford.