Nazarani Stambhas or open-air crosses of St Thomas Christians

Throughout history, marking and venerating certain places has been integral part of human culture. From menhir to stele, obelisk to freestanding columns, pillars to crosses—each marked a certain place, commemorated certain events and also functioned as both object and as a medium for veneration. Standing stones are seen as the axis mundi, the cosmic centre which is also symbolised by the world tree. Usually, these megalithic structures denote a burial site more significant of the death cult. To a certain extent, it can be said that Christianity too has appropriated the death cult with its acute focus on the image of Christ on the cross. Even the similar practice of erecting gravestones served the same purpose as those of ancient standing stones (Varner 2004:86). But the complex symbolism of the cross is not limited to the scope of being a mere symbol of death; it expands to multiple symbols. It is the symbolic Tree of Paradise, signifying, by turn, a bridge or ladder by means of which the soul may reach God, suffering, resurrection, axis mundi, etc. The monumental stone crosses of St Thomas Christians can be placed within these contexts.

The cross or crucifix is the central symbol of Christian art. However, the cross as a symbol was found throughout cultures. It is one of those symbols which has been in usage since prehistoric times. The earliest representation of cross was as the alphabet ‘T’ which derived from the Greek letter ‘Tau’.

During the early centuries of the Roman Empire, crucifixion was seen as a symbol of torture and pain. One of earliest images of the crucified Christ is supposedly a piece of Roman graffiti, known as the Alexamenos graffiti. It depicts an young man worshipping a crucified donkey headed figure with the inscription roughly translated as 'Alexamenos worshipping (his) God'. The graffiti was apparently meant to mock a Christian named Alexamenos. In Early Christianity, the symbol of the crucifix was considered as a symbol of shame, being equated with the gallows. The Early Christian imageries usually featured shepherds, priests, priestesses, etc. There are not any known image references prior to 3rd century AD. Though the image of the cross was present during the early century, its veneration was not part of Early Christian worship until as late as 4th or 5th century AD. The crucifixion imagery coincides with the pilgrimage of the Holy Land in the 4th century and dissemination of the Cross by Helena, Empress Mother of Constantine, the Byzantine emperor.

There are many variants of Christian crosses used today throughout the churches, some as part of jewellery, on books, on gravestones, to mark a certain site, some are erected as a mark of subjugation of that place indicating the victory of Christianity, while some are placed in market centres and in front of churches.

The public-square crosses were usually erected in the open courtyards of churches; hence the name ‘public square’ (also known as praca or plaza or piazza). Even today, there exist many open-air crosses throughout the world. Some examples are the market-square crosses and the Pictish crosses in Scotland and Northern England, the Celtic high crosses in Ireland, and the Armenian crosses popularly known as khachkar. Both Pictish stone crosses and Celtic crosses were erected by the Celtic Christian missionaries. The insular ornamentation of these crosses was the continuation of the regional style which developed during the post-Roman Empire period. These high crosses were usually placed in precincts of churches, convents, monasteries or market centres. Both the Spanish and Portuguese empires used to erect high crosses throughout the churches and monasteries of their colonial empire. They were erected as symbols of the victory of colonial power over native cultures.

The Portuguese Empire in India erected similar crosses throughout their colonial conquest as well as in places they had influence on the local power or community. Stylistically, we can group these crosses in India into two main groups: Indo-Latin and Indo-Syrian. The Indo-Latin style was prevalent more in Goa and other places which were under the influence of the Roman Catholic Church: it was culturally influenced by the Iberian Peninsula. It was brought to those regions by the European missionaries under the Portuguese monarchy. The Indo-Syrian style, on the other hand, was an indigenous one developed within Kerala and followed by St. Thomas Christians, and are only found in their churches.

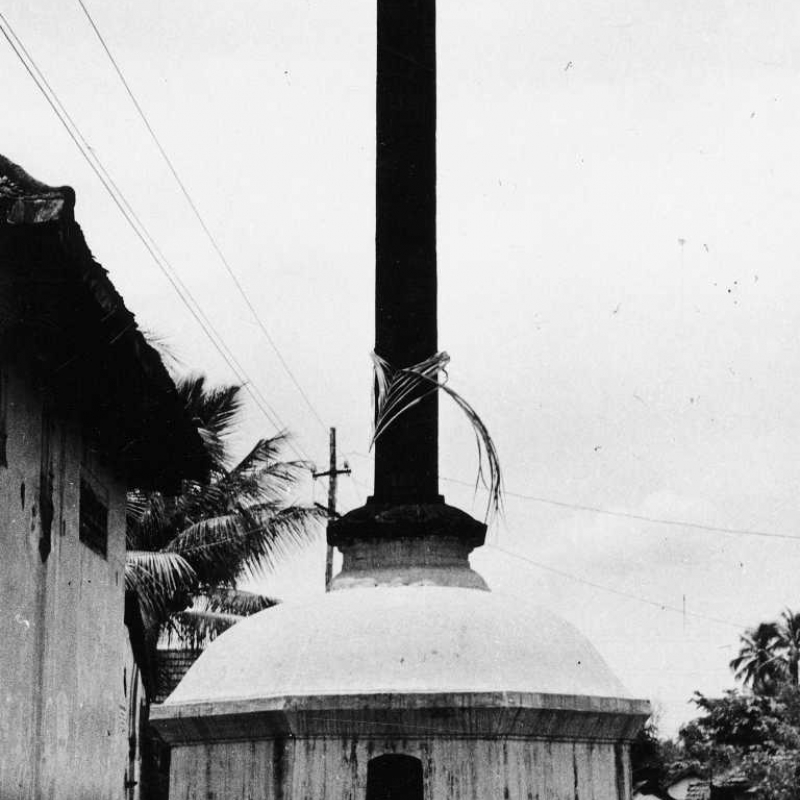

The Indo-Syrian high crosses evolved from the Indo-Latin cross as some of the early high crosses in St. Thomas Christian churches were of Indo-Latin style. The Indo-Latin style has evolved from the tradition of padroas and praca crosses; the padroas were large stone crosses with the Portuguese coat of arms, which was placed on land claimed by the Portuguese Empire. The early crosses were constructed under the direct control of the Portuguese Empire. These high crosses were usually placed on an octagonal platform with arched niches at the centre, topped by a circular dome at the foot of the cross. The niches in the pedestal usually contained images of the saints. In Goa and other erstwhile Portuguese colonies this style is further elaborated and articulated.

The St. Thomas Christian Churches usually came under the dominion of the local ruler thus restricting inclusion of the Portuguese Empire. Prior to the division of St. Thomas Christians into the Catholic and Orthodox (Oriental) sects, the European missionaries tried to bring the St. Thomas Christians under the Roman Catholic Church, condemning their existing practices as being those of heretics. They started the process of Latinising the St. Thomas Christians by various methods, one of them was by translating the Latin prayers into Syriac (the language of Liturgy of St. Thomas Christians). This eventually led to the Synod of Udayamperoor in which many practices of St. Thomas Christians were condemned and many manuscripts were burned citing them as heretical. This period also saw the deployment of European architectural styles for the churches of St. Thomas.

Though it has been said by various scholars that the pre-Portuguese Churches of St. Thomas Christians had wooden crosses in front of them, it is hard to verify this. The existing stone crosses, it may be said, were mostly constructed after the 16th century (Pereira 2000). The Indo-Syrian crosses and the Indo-Latin ones are differentiated by the very styles in which they have been constructed. Indo-Latin crosses are found throughout the Portuguese colonies in India. They are both in octagonal and square base plans, and are occasionally found in Kerala in both the St. Thomas Christian and Latin Christian churches. The cross is placed on a multi-tiered pedestal. The pedestal is usually in square or octagonal plan, with occasional baluster column or lesenes at the corners and arched niches at the centre of each face. The pedestal is topped by entablature with clusters of concave volutes at the corner or a hemispherical dome topped with a plain or patriarchal cross.

In contrast to the Indo-Latin crosses, Indo-Syrian crosses can only be found in the churches of St. Thomas Christians. These crosses are monumental in size. Similar to Indo-Latin crosses, these crosses are placed on multi-tiered pedestals representative of the local architectural style. The pedestal is similar to the balikkal/ balipitha (sacrificial stone) found inside brahmanical temples. The balikkal/balipittha is placed in front of the garbhagriha (sanctum sanctorum) of the temple, within the antarhara (inner courtyard) facing the srikovil (sanctuary). These structures have a moulding similar to that of the temple: the adisthana (basal moulding), which includes the upana (bottom adisthana moulding), jagati (vertical moulding at the base of adisthana) and kumuda (minor torus in adisthana). Occasionally, above the kumuda, central niches have the ghanadvara (false door) which is topped by a makara torana (makara arch). The central topmost portion is topped by the kapotavpali (cornice) with an occasional bharavahaka (supporting dwarf), and this is topped by a padmaka.

These crosses also echo the manastambhas (pillars of honour) found in the Jain temples of Karnataka. These pillars are monolithic columns, errected on a pitha (pedestal) structure, topped with a mandapa pavilion which enshrines the Jina figure. They are placed in front of the Jain sanctuary. These columns commemorate the victory of the Jina over all passions. In St. Thomas Christian churches, stone crosses are also placed on a similar pedestal.

As mentioned earlier, the pedestal has mouldings similar to that of the ballikkal (Poduval 2001). The pedestal is divided into three parts: The base portion is in a square plan with central projections, which is topped by an octagonal base, followed by a circular base with a hemispherical dome acting as the base of the cross. At times, instead of an octagonal or circular plan, a square plan is followed. On the square base, the kantha (recess) contains pilastered niches with icons such as the sun, moon, angels and animals related to Christian iconography. These pilasters are topped with a lotus bud capital (puspapotika). The kantha is topped by a moulding kapota (curved cornice) with kudu (blind chaitya arch) or nasi (horse-shoe shaped window arch) at regular intervals. These moulding designs are repeated again on the octagonal and circular base. The circular base is then topped with padmaka over which the monumental cross is erected. The plain crosses contrast the repetitive mouldings and carved niches of the pedestal.

The pedestal of the monumental cross in Kaduthurthy is profusely carved with Biblical imageries, such as Jonah and the whale, Mother Mary and Infant Jesus, and the apostles Paul and Peter. There is also a miniature version of crucified Christ with Mother Mary and Magdalena Mary at the feet of the cross. At the corner of the quadrangle base of the cross, small elephants are carved. Images which symbolise the resurrection of the Christ, such as the peacock, peahen and roosters, are also used; Indian elements, including the use of lions and elephants, can also be seen.

The granite cross is usually carved without any images; however, there are exceptions like the cross of the Old Syrian Church in Chengannur which is carved with foliage and angels. Another exception is the Cross of Arma Christi, Chenganoor (Reitz 2001). Arma Christi (Weapons of Christ) or the instruments of Passion is part of medieval European Christian symbolism associated with the Passion of Christ. They include reed, robe, Titulus Crucis, Holy Grail, dice, rooster, ladder, hammer, pincer, myrrh, shroud, sun, moon, thirty silver coins, hand, chains and swords. These instruments are symbolic of the sufferings Christ had to endure during his crucifixion. According to the theology of Eastern Syrian Church, the empty cross symbolised the resurrection of the Christ, not his suffering. With the Synod of Udayamperoor, the theology of Western Catholic Church was forcefully placed upon the St. Thomas Christians.

The cross of St. Thomas Christians thus serves both as the axis mundi and the evidence for suffering of Christ. The cross becomes the centre for the surrounding place. It is not just a marker to distinguish church and temple but rather it acts as the ladder, the epicentre. Even today devotees venerate these crosses. It is an integral part of their day-to-day worship. People light lamps and pour oil on the pedestal of these crosses as acts of veneration. There is no doubt that the cross was thus appropriately used as a symbol in the Koonan Kuris oath (1666), where every person from the community gathered and touched the cross as an act of protest against the Portuguese Padroado.

Unlike the Portuguese Padroado crosses, it cannot be said that these crosses were erected to show the superiority of Christainity and the Portuguese over the local people. The Padroado crosses were usually placed where the Portuguese empire was in control, unlike in Kerala where the Portugese colonialists had limited influence over the local empire (Reitz 2001). Instead the St. Thomas crosses were more symbolic as a statement of an identity. If we observe, these particular crosses are only found within the complex of St. Thomas Christian churches. These crosses are, in a way, a part of the process of enculturation that had happened with the interaction of various cultures. Just like using the Syriac language to translate the Latin sermons, local architecture and sculptural tradition were used to depict a foreign element.

This article is not a definite answer to the development of these granite crosses, rather it seeks to trace the potential symbolic meaning of these crosses and the origins of their symbolism. Over time, these crosses have undergone several stylistic changes, but the purpose of the 'cross' remains the same. Today, it has become an unavoidable aspect and a unique feature of the St. Thomas churches.

References

Pereira, Jose. 2000. Baroque India: The Neo-Roman Religious Architecture of South Asia: A Global Stylistic Survey. New Delhi: IGNCA.

Poduval, Jayaram. 2001. ‘Kochi, Beginnings of European Architecture in India.' Marg 53 (2): 12–23.

Reitz, Falk. 2001. ‘Is the Origin of the Granite Crosses Kerala Indigenous or Foreign?’. In Tohfa-e-Dil: Festschrift Helmut Nespital, edited by Dirk W. Lonne, 799-819. Reinbek: Verlag für Orientalistiche Fachpublikationen.

Varner, Gary R. 2004. Menhirs, Dolmens and Circles of Stone: The Folklore and Mythology of Sacred Stone. New York: Algora.