Until the 1930s, nautanki had no women actors; men took on all female roles. Once women joined, however, they quickly achieved popularity and stature as star attractions, often overshadowing the men. The rise of heroines in nautanki paralleled the rise of heroines in Bollywood: leading ladies were soon household names in India’s Hindi belt. Nautanki began to be labelled a ‘woman-dominated form’, and several successful nautanki heroines even launched their own production companies. Here, we trace the life and works of some well-known leading ladies of the Kanpur shaili (style) of nautanki.

Gulab Bai

In 1931, 12-year-old Gulabiya (as she was fondly called) accompanied her father to the Makanpur mela, where they saw Raja Harishchandra, performed by Tirmohan Lal and Company. Fascinated by the nautanki, she wished to join the company. When Tirmohan Ustad heard her sing, he agreed to take her in at a salary of a few annas per month. This is how Gulab Bai, known as the first female actor in nautanki, began her professional journey.[1]

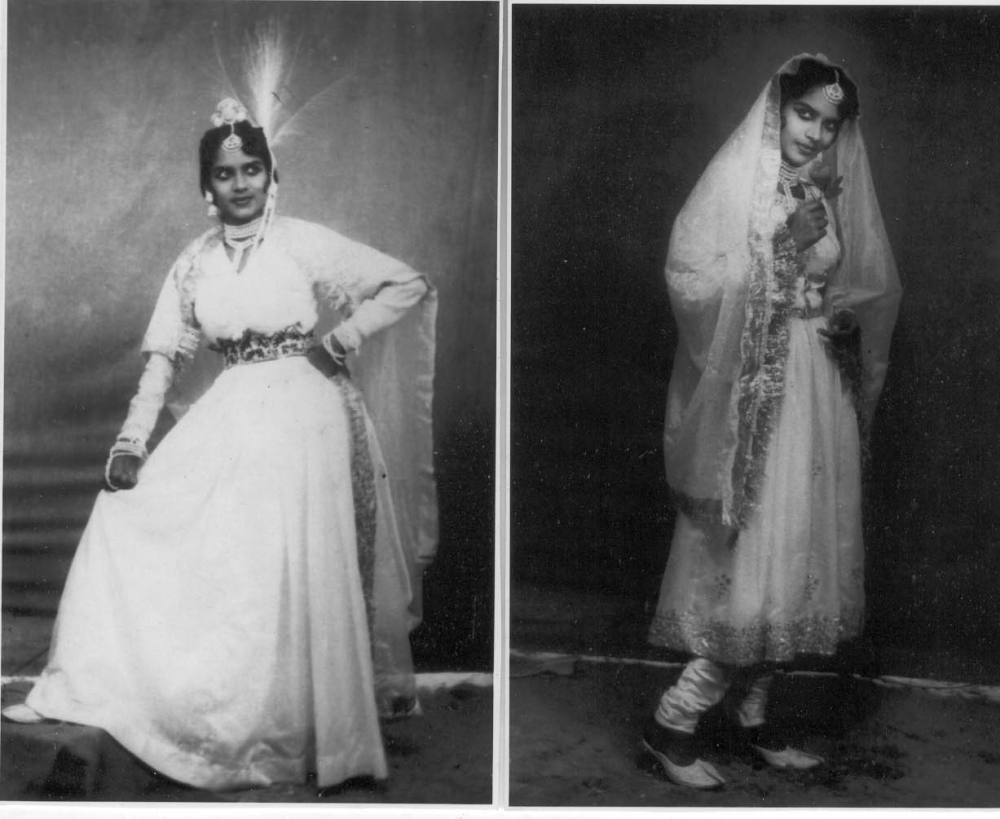

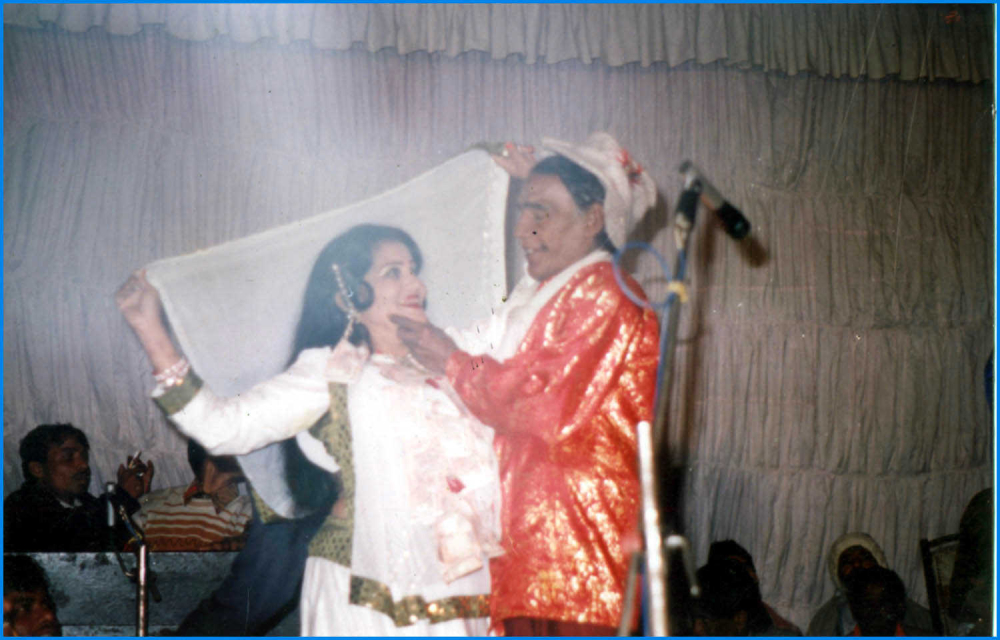

Gulab Bai systematically learnt nautanki singing and acting, and soon began playing leading roles in nautankis: Rani Taramati in Raja Harishchandra, Laila in Laila Majnu, Heer in Heer Ranjha. By the mid-1930s,Gulab Bai was famous and the company was doing well; she was said to be earning more than the district magistrate in the 1940s! She acted and sang dadras and rasiyas (folk and semi-classical genres) in between drama scenes; several of her songs were recorded and became extremely popular.[2] (Figs 1 and 2)

Gulab’s sisters Chahetan Bai, Paati Kali and Sukhbadan also joined the nautanki world. The sisters bought a house in Rail Bazaar, Kanpur, lived there, and worked together—Gulab and the youngest sister, Sukhbadan, as heroines, Chahetan as side-heroine, and Paati in comic roles.[3]

In the mid-1950s, Gulab Bai set up her own nautanki company, the Great Gulab Theatre Company. She had some 70 people on the rolls, including actors, musicians Mohammed Khan Saheb, Rashid Khan Warsi and Mehboob Master, and talented parda (drop-curtain) painters Babban from Lucknow and Nazeer from Agra. Gulab managed the affairs of the company, directed plays and trained actors.[4]

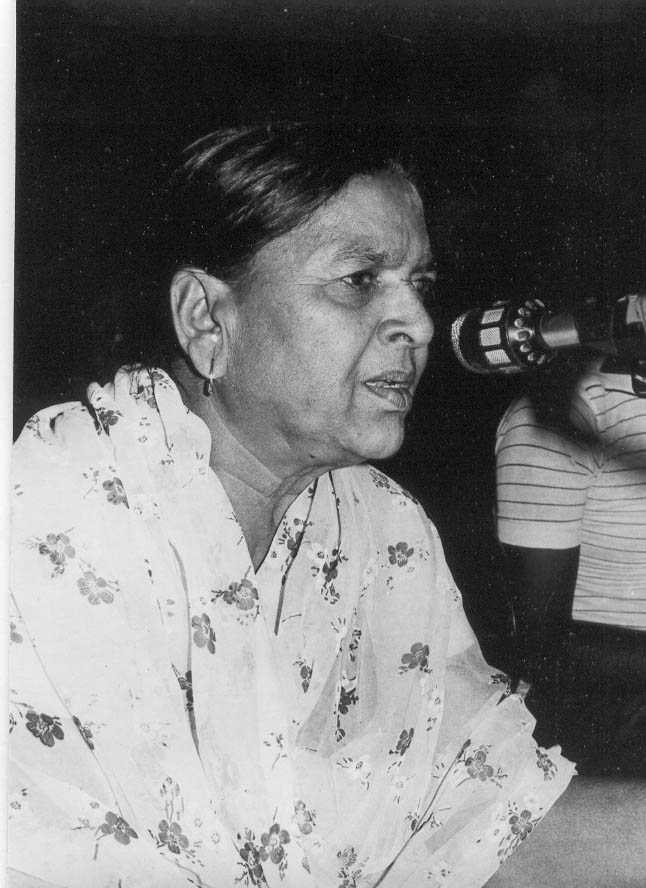

Gulab Bai received national recognition in the form of a Sangeet Natak Akademi Award (1985), the Padma Shri (1990), and Yash Bharati Award (1995). She breathed her last in 1996.[5] (Fig. 3)

Sukhbadan Bai

Sukhbadan learnt to enact heroine roles from her sister, Gulab Bai, some 20 years elder to her. Initially, Sukhbadan was nervous, often getting so tense that she would refuse to go on stage. On one such occasion, Gulab sent for half a glass of desi sharab (country liquor), and asked her kid sister to drink it; sure enough, it helped Sukhbadan to relax, go on stage and act with aplomb! A pre-performance peg became a practice with Sukhbadan, which she continued over the years.[6]

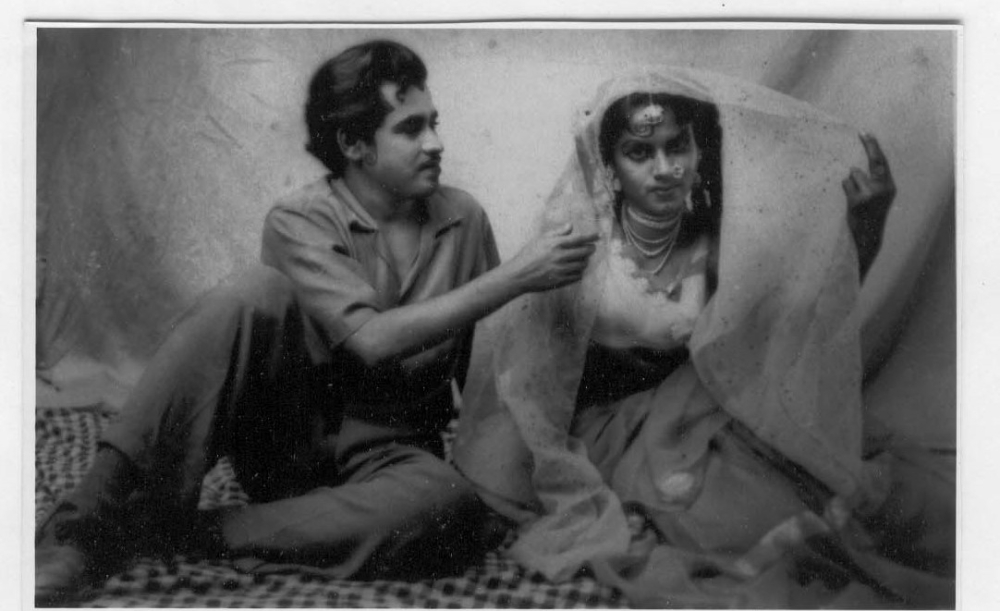

Once, when Gulab and Sukhbadan both acted in the same nautanki, audiences expressed their preference for the younger actor. Rather than feel slighted, Gulab Bai was delighted at her sister’s success and gladly passed on the mantle of the heroine to her. Sukhbadan became a wildly popular leading lady of countless dramas—though, after a few years, she chose to marry and retire. (Fig. 4)

Kamlesh Lata

Kamlesh Lata joined nautanki in the 1960s and was still acting as heroine some 40 years later. ‘Today’s girls do not know how to act,’ she explains, ‘so, if someone is doing a proper nautanki play, they look for older actors, like me!’ She adds, with frank confidence, ‘I can act much better than actresses in Ekta Kapoor serials! In nautanki, we sing, dance, speak and express emotion, all at the same time. Now, girls act but do not know how to sing or dance. Some girls dance but cannot act or sing!’

Kamlesh Lata grew up in Nadgaon village, Etawah district of Uttar Pradesh. Her sisters Mala, Chanchala and Allo became well-known nautanki actors as well. Kamlesh’s real name is Qureshi, and Mala’s is Mallika; initially, they worked in a nautanki company in Mathura. Their talent attracted the attention of Krishna Bai, a celebrated heroine who had started the Krishna Nautanki Company. Krishna Bai’s husband, Hamid Bhai, who helped her manage the company, went to Nadgaon to recruit the four sisters. ‘We did not want to go,’ recalls Kamlesh Lata. ‘We had heard Kanpur women are too bold. But when we went, we found they were the same as us.’

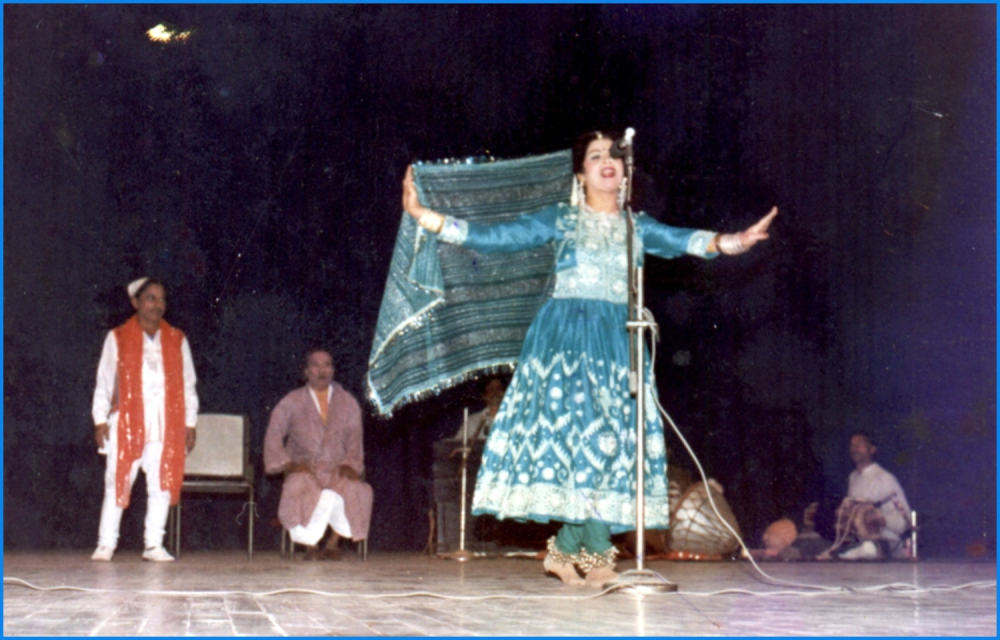

Kamlesh has acted as a heroine for many companies, including Krishna Bai’s, Gulab Bai’s, and the Mala-Chanchala Nautanki Company, launched by her sisters Mala and Chanchala. (Fig. 5)

She notes spiritedly, ‘Today, people say nautanki is bad. If it is bad, why were we given hundreds of certificates and testimonials? Do people give testimonials for doing something bad?’ She brings out a file full of documents that testify to her rich contribution to nautanki over the years, and adds, ‘In our time, there was no obscenity. We wore full costumes. Only the face and hands could be seen.’[7]

Mona

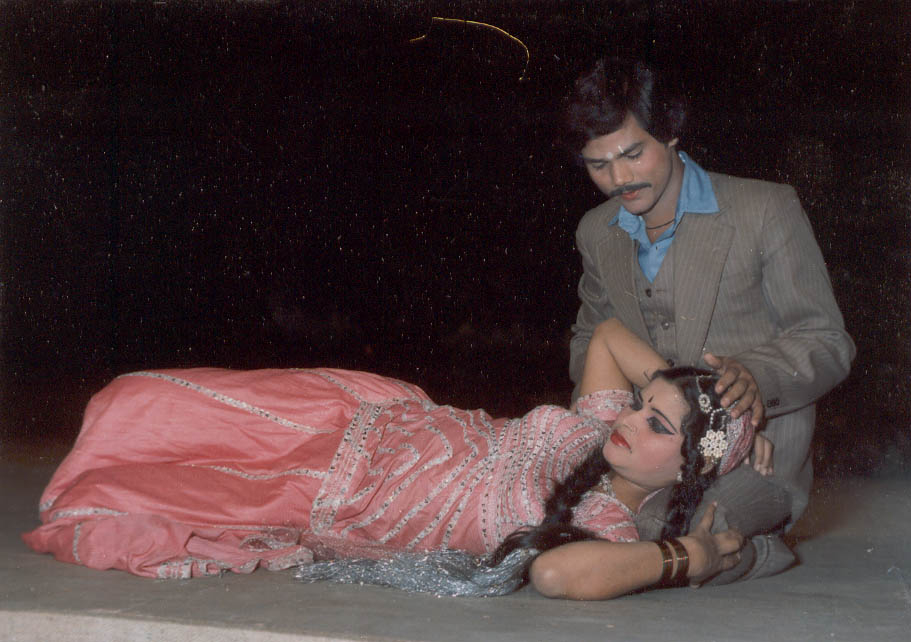

Mona worked as a heroine with several companies in UP and Bihar, and performed in nautankis such as Anarkali, based on the Bollywood film, Mughal-e-Azam (1960). The costumes Mona wore while acting as the lead character of Anarkali matched some of Madhubala’s in the film. (Figs 6 and 7)

Another popular nautanki that Mona performed in was Daku Phoolan Devi. Her performances at Rajgir, Bihar, were particularly memorable: ‘At the Rajgir mela, when I acted as Phoolan Devi, I would make my entry on stage on a horse,’ she recalls, laughing, ‘Old-timers still remember the dramatic entry.’ The Rajgir mela was a fair for horse-trading, so it was easy to get a suitable horse!

In the mid-1980s, Mona set up a company along with her husband and produced nautankis for several decades. After his death, she chose to live with her sister, Beena, who also was a retired nautanki actor. Their dramatic past lurks, barely suspected by others in the neighbourhood, within Kanpur. Mona says, ‘I can sing whole nautankis for you—the entire script, not just my part. I remember all the lines from Phoolan Devi, Anarkali, and so many other nautankis even today!’[8]

Neelam Suraiya

Suraiya began acting at the age of five, under the stage name Neelam Suraiya. A versatile actor, she worked in Krishna Bai’s, Gulab Bai’s and several other companies. (Fig. 8) Her mother Lallan Bai (who always acted as a side-heroine) and father Master Nishar were nautanki actors too, in Lalman Numberdar’s, Krishna Bai’s, as well as other companies.

Suraiya’s elder sister, Pauva, took the stage name Kamini Kaushal and shot into prominence as a heroine at the age of 15; the legend goes that V. Shantaram went to Kanpur to offer her a film role. At the age of 16, however, she died, possibly poisoned by rivals in the nautanki field.

Suraiya graduated from child roles to heroine roles and soon became quite the rage. She recalls a performance in Alu Mandi, Kanpur, during which the all-male crowd began snatching the microphone and harassing her. Suraiya was whisked off tosafety, escaping from the shringar room (an improvised greenroom) via lanes and by-lanes. She never performed in Kanpur city again.

Suraiya married ‘Darji Master’ Ram Raj, who specialised in stitching nautanki costumes. Leading ladies earlier got their costumes stitched by Master Azam in Lucknow, until they discovered that Ram Raj, at Pakeeza Tailors, Kanpur, stitched their dresses quite as well. Ram Raj says, ‘Wealthy men come to see nautanki and gaze at the leading ladies. I fell in love with Suraiya, and in her heart, she too liked me.’[9] They had four daughters, all educated and married.

Suraiya kept acting well into her 60s, whenever she was offered a good role. She says, ‘At places like Unnao and Bheegapur, the public still wants good nautanki. If I perform on stage, you think the public will not watch? If I agree to go somewhere, I write on my letter pad, “I will do the nautanki at such-and-such time.” Otherwise, their variety programme goes on, and we actors are kept waiting!’[10]

Asha

Asha, Gulab Bai’s daughter, travelled with her mother’s troupe from childhood, and took on heroine roles as she matured. She captivated audiences with her powerful singing and attractive stage presence. In no time, she was an established star. (Fig. 9)

During the 1980s, when the Great Gulab Theatre Company performed Aurat ka Pyar urf Bahadur Ladki for national television, as well as at New Delhi’s Mavalankar auditorium, it was Asha who played the leading lady. Aurat ka Pyar urf Bahadur Ladki was a nautanki Gulab Bai famously performed in Kanpur in the 1940s, the British not only banned the play but also the actors from the city limits.

Asha was superb both as an actor and singer. (Fig. 10) However, once she married, she withdrew from stage for several years.[11]

Madhu Agrawal

Madhu Agrawal, Gulab Bai’s younger daughter, was studying at university when she agreed to take on a heroine role in the Great Gulab Theatre Company, to help tide over a financial crisis. Once she joined, however, there was no looking back, for she was a brilliant actor, vivacious and talented.[12] (Fig. 11)

In 1996, the Great Gulab Theatre Company was invited to perform at the Vishwa Hindi Sammelan, Trinidad and Tobago. The group performed Amar Singh Rathore with Madhu as the heroine, Haadi Rani, to a rapt audience. Later that year, Gulab Bai passed away, and Madhu took over the management of the company.

In 1997, the company produced a brand new nautanki, Teen Betiyan urf Dehleez ke Paar, a contemporary sociodrama based on the tragic joint suicide by three sisters in Kanpur. (Fig. 12) Madhu and Asha acted as two of the sisters. Produced in collaboration with the director Tripurari Sharma, the nautanki’s moving storyline, music and artistry were much appreciated by audiences in Kanpur city.[13]

Madhu Agrawal continued producing and directing nautankis upon invitation for the next 15 years, including Anarkali at the Sangeet Natak Akademi, Lucknow; Amar Singh Rathore and Raja Harishchandra in Bhopal; and Sultana Daku at the India Habitat Centre, New Delhi.[14] (Fig. 13)

Notes

[1] Salil, `Gulab Bai.’

[2] Mehrotra, Nautanki ki Malika, 100, 136–37.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Shiv Adhar Dube, in conversation with the author, July 2003.

[5] Mehrotra, Gulab Bai, 221.

[6] Sukhbadan, in conversation with the author, May 2003.

[7] Kamlesh Lata, in conversation with the author, May 2003.

[8] Mona, in conversation with the author, May 2003.

[9] Ram Raj, in conversation with the author, June 2003.

[10] Neelam Suraiya, in conversation with the author, June 2003.

[11] Madhu Agrawal, in conversation with the author, May 2003.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Mehrotra, Gulab Bai, 10–12.

[14] Madhu Agrawal, in conversation with the author, September 2012.

Bibliography

Mehrotra, Deepti Priya. Gulab Bai: The Queen of Nautanki Theatre. New Delhi: Penguin, 2006.

———. Nautanki ki Malika Gulab Bai. New Delhi: Penguin, 2010.

Raghav, Krishna. 'Ek Thee Gulab.’ Rang Prasang, Jan–Jun 2000, 19–42.

Salil, Suresh. ‘Gulab Bai.’ Jansatta, Sep 9, 1999.