Nautanki is an operatic theatre form combining music, dance, story, dialogue, humour, pathos, melodrama and wit in a magical whole. Nautanki, earlier known as svang, originated in the late nineteenth century in Uttar Pradesh (then United Provinces of Agra and Oudh) and steadily gained popularity. Performances were held in the open, on a provisional stage, and attended by entire villages—men, women, and children—who watched, spellbound, from late night to early morning. Nautankis were also performed in towns and cities, in bazaars, parks, residential colonies and at factory gates.

Nautanki drew from various sources. Its forerunners include bhagat (a 400-year-old form of dramatised religious singing with a thin storyline); ballads that were sung by itinerant bards; and improvised skits performed by ordinary people during festive occasions.[1] Like Punjab’s nakal, Maharashtra’s tamasha, Rajasthani khayal, Tamil Nadu’s natakam, Bengal’s jatra and Madhya Pradesh’s maanch, nautanki exhibits a blend of local and Western dramatic conventions. All these genres may, therefore, be termed ‘intermediary’ or ‘hybrid-popular’ theatre forms.[2] Some of these forms are religious, while others, like nautanki, are secular.

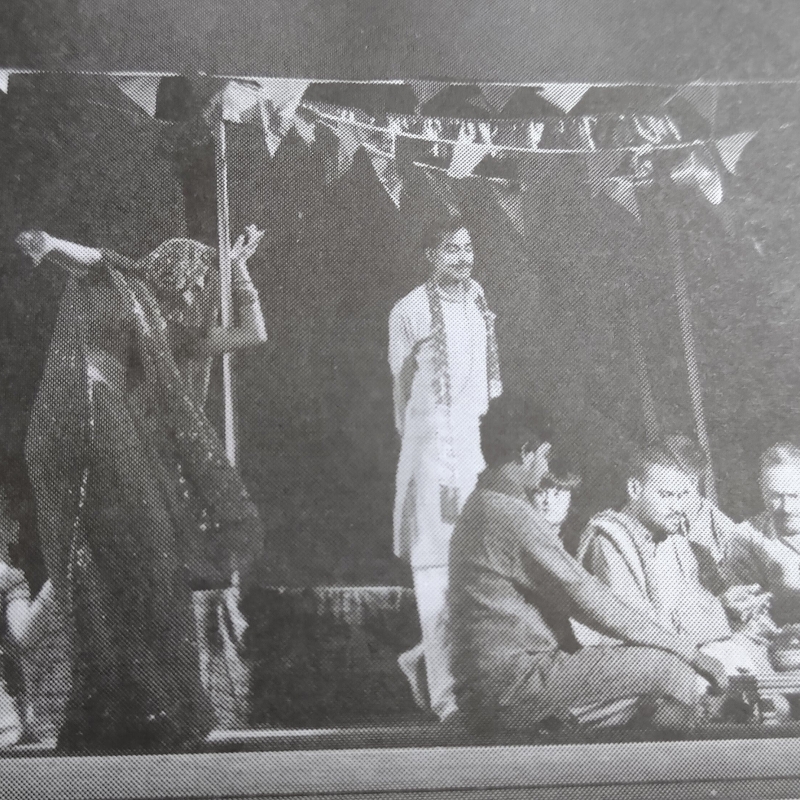

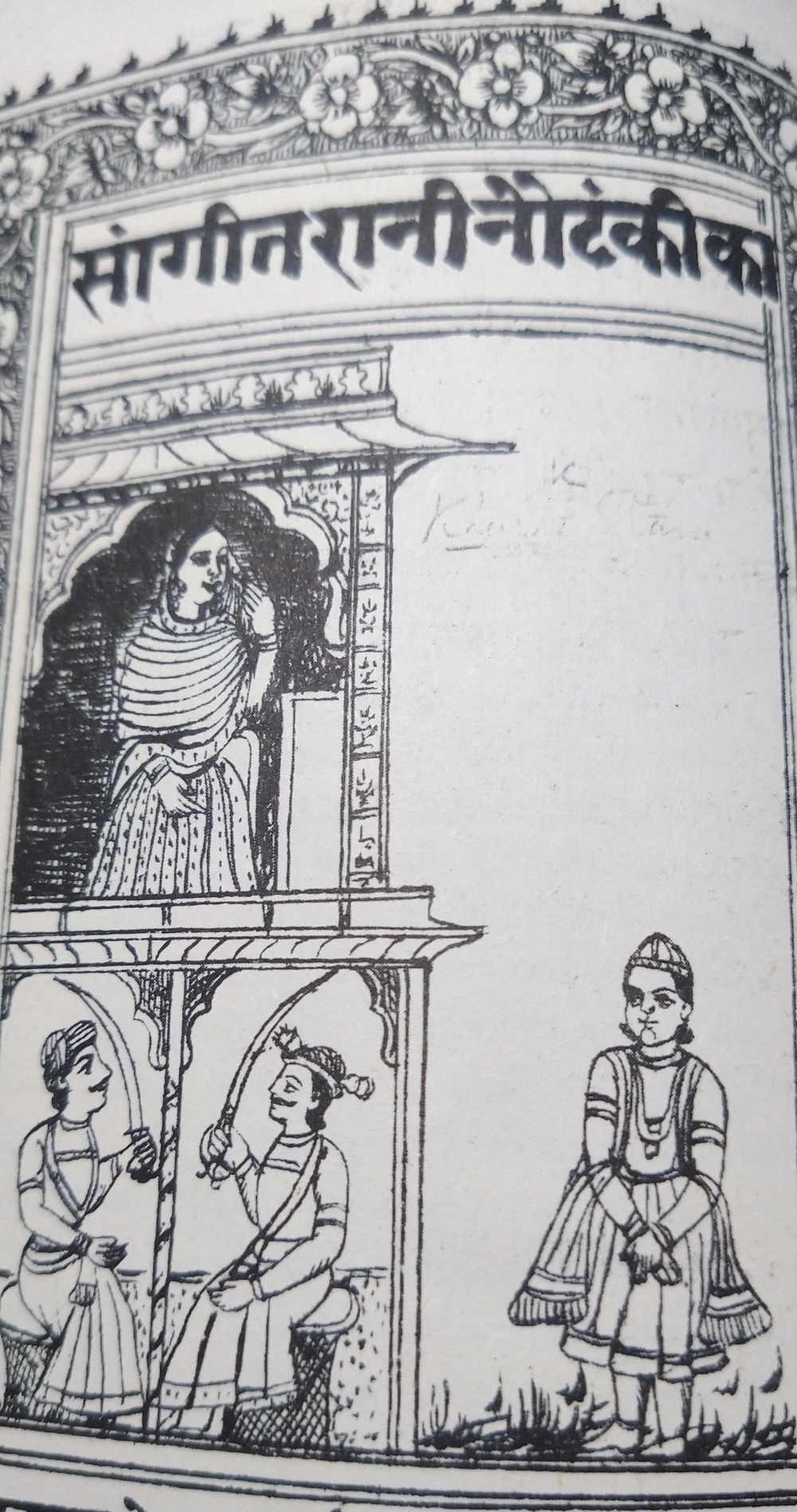

The first svangs were produced in Hathras, a town in UP, within an akhara (all-male space for the practice of music, poetry, drama, wrestling and bodybuilding) established by Indarman. Indarman, a poet from the Chhipi (artisans who print cloth) caste, began exhibiting svangs in the 1890s, with his disciples Chiranjilal and Govind Ram. Natharam Gaur, a boy from Dariyapur village, joined Indarman’s akhara and became his most illustrious disciple—an accomplished singer, dancer, composer and actor, playing even female parts with flair. In the 1990s, Natharam’s troupe, with Chiranjilal and other actors, began travelling and performing in various parts of UP. The troupe became extremely popular during the next few decades, with Vidyadhar, Ganeshi Lal, Nazeer Khan, Manohar Sharma, Giriraj Prasad, Chunnilal Hathrasi, Vajeera, Nanua, Bhola Nath and other actors, as well as Mohammed playing the nakkara (kettledrums), Ghoore Khan the harmonium, and Khairat Miyan the dholak.[3] One of the svangs performed by Natharam’s troupe was Shehzadi Nautanki (Princess Nautanki, a folk tale from Punjab), which became extremely popular, especially in the Kanpur area, so much so that the form itself began to be called nautanki. (Fig. 1)

By the 1910s, Kanpur became an important centre for nautanki and developed a distinctive style. Of the two main styles of nautanki, the Hathras shaili (style) remained closer to the svang with its emphasis on Hindustani classical singing, while the Kanpur shaili emphasised dialogue, facial expression and acting. A Hathras nautanki would begin with the dhrupad (an ancient style of classical singing), requiring singers to hold notes unbroken, sometimes for three or four minutes at a stretch. In Kanpur nautankis, music was less elaborate, while stagecraft was increasingly refined.[4]

By the 1930s, nautanki developed as a commercial form. Sale of tickets facilitated its economic growth, and the akhara system began to give way to companies managed professionally, particularly in the Kanpur area. Companies often employed a staff of up to 80 persons and paid monthly salaries. Partly under the influence of Parsi theatre, nautanki adopted a wide spectrum of modern conventions, including the proscenium stage with painted backdrops, wings and front curtains, lavish dresses and instruments such as the harmonium and clarinet.

Nautanki was initially an all-male genre in which male actors enacted women’s roles. However, from the 1930s, women joined nautanki troupes as actors; this trend was far stronger in Kanpur than in Hathras. Women contributed to the spectacular success of nautanki, so much so that it began to be labelled a ‘woman-dominated form’. However, public attitude towards women actors were generally prejudiced—even though, as Kamlesh Lata, an ageing actor, notes, ‘In our time, there was no obscenity. We wore full costumes. Only the face and hands could be seen.’[5] Women artistes felt respected and safe within the artiste community though they sometimes faced threats and harassment from members of the audience.

Plays and Performances: The Medium and the Message

Nautankis were a regular feature at annual melas (fairs), such as those at Makanpur, Bahraich, Kashipur, Meerut, Sonepur, Rajgir, Badaun, Bijnaur and Devi Paatan, each of which drew thousands of pilgrims and revellers. A pair of nakkaras, hallmark of the nautanki genre, produced the characteristic beat which could be heard for miles around. A nautanki, whether in Hathras or Kanpur shaili, always began with an invocation to Goddess Saraswati and Lord Ganesha. The ranga or sutradhar (stage manager, a classical convention inherited by nautanki) would render a musical synopsis of the entire story, after which the action would begin. Characters were sharply etched, events fast paced, and movements rhythmic. Nautanki actors’ voices were audible over long distances, unaided by microphone in the early years. Ragas such as bhairavi, bilawal and khamaj were commonly used, adapted, and rendered with vigour. The verse pattern was divided into doha (couplet), sung free without any beats; chaubola (quatrain metre), the main stanza; and daur (an accelerated section in quadratic metre), sung at a great speed before slowing down at the end. The nakkara was played towards the close of each portion. Throughout the play, various melodies and embellishments were used, accompanied by instrumental music.[6]

From the start, nautankis reinterpreted a wide range of literature and oral tradition including legends, Sanskrit dramas, Persian romances and mythological lore. Some of the most popular nautankis, which drew inspiration from these diverse sources were Raja Harishchandra, Laila Majnu, Shirin Farhad, Indar Sabha, Shravan Kumar, Puran Bhagat, Roop Basant,Bhakt Prahlad, Heer Ranjha, Dahiwali and Bansurivali. Plays based on historical characters like Prithviraj Chauhan, Amar Singh Rathore, Rani Durgavati and Panna Dai were also popular. Gods, goddesses, wizards and fairies mingled with kings, queens, maids, dacoits, landlords, rebels, gardeners, housewives, lovers, saints and robbers, creating a fanciful world which appealed to emotions and aesthetic senses.

Nautanki aficionado Krishna Raghav writes:

When Harishchandra asks Taramati to pay tax for the cremation of Rohtas, believe me, people would burst into tears. When Majnu goes mad and meets Laila in Laila Majnu, when Farhad beats his head against Shirin’s grave in Shirin Farhad, when Haadi Rani breaks her bangles in Amar Singh Rathore, when Sultana amazes the British police commissioner in Sultana Daku, there is emotion created… The actors and audience would become one, no artifice on either side.[7]

The lavani (a traditional poetic metre) was particularly effective in expressing mourning, and several nautanki actresses developed into powerful lavani singers, including Shameem Banu of Lucknow, Nur Jehan Begum of Allahabad, Tara Devi of Hameerpur, Radha Rani of Pilibhit and Kamlesh Lata of Mathura. According to nautanki expert Krishnamohan Saxena, ‘Amar Singh Rathore and Raja Harishchandra nautankis have been enacted around 1,00,000 times each, because the lavanis Haadi Rani and Taramati sing to express grief, arouse such strong emotions in the audience!’[8]

Nautanki functioned as a medium of entertainment as well as ethical, political and social education. Various plays consolidated moral, sociocultural and political values within their plots, conveying messages relevant for the contemporary age. Heroes and heroines of nautankis like Sultana Daku, Daku Maan Singh and Dayaram Gujar were outlaws serving the poor. In plays such as Virangana Veermati, Shrimati Manjari and Bekasur Beti, women, including ill-treated daughters and daughters-in-law, battled valiantly for justice. Raja Harishchandra, Puran Bhagat and several other nautankis taught an ethics of renunciation and selfless pursuit of truth. As cultural historian Kathryn Hansen notes, nautanki ‘was anything but marginal to social and cultural processes.’[9]

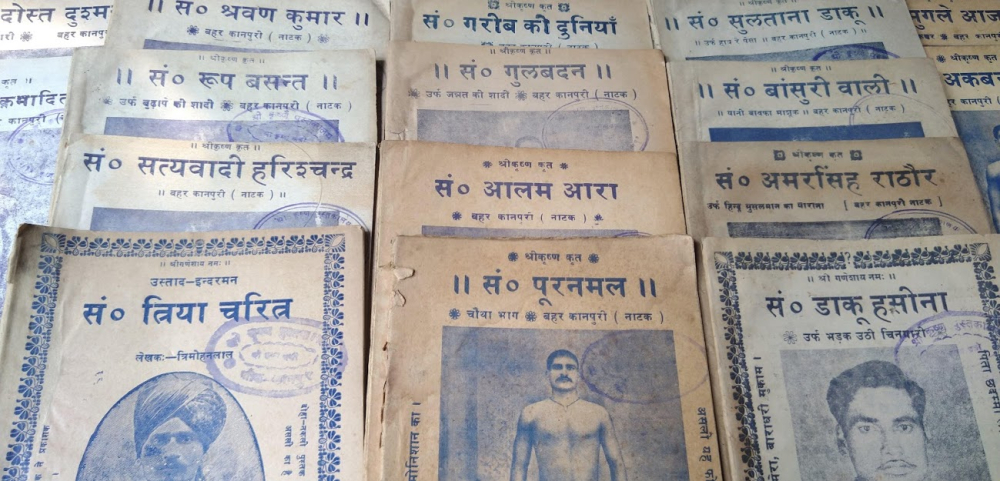

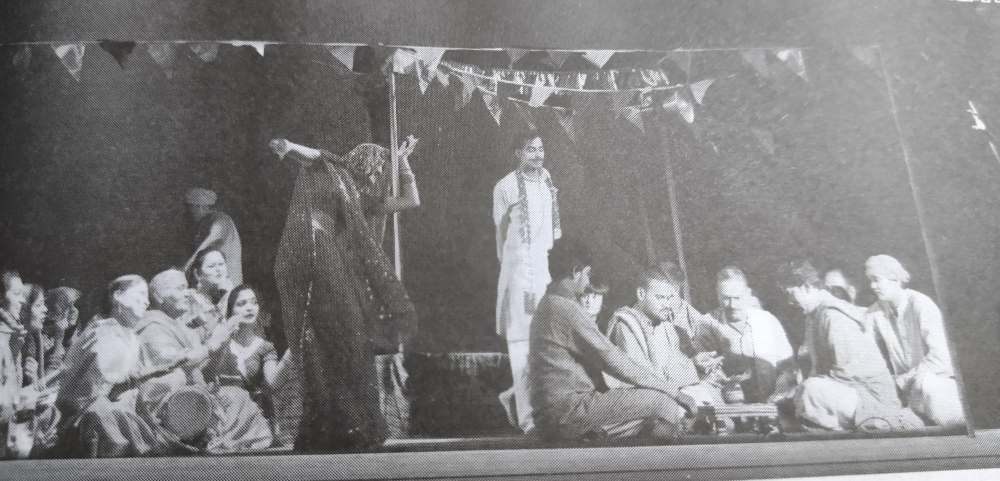

Hundreds of nautanki script books were published by various publishers, including Shyam Press set up by Natharma Gaur in Hathras and Shriskrishna Pustakalaya which Shrikrishna Pehelwan ran in Kanpur. Language in nautankis was simple and direct, including Urdu, Brajbhasha, Rajasthani, Hindi and local dialects. (Fig. 2) Although nautankis were generally not assessed as literary works, perhaps because of their language, their script books sold better than bestsellers in Hindi or Urdu. Wholesale dealers would weigh the cheaply printed plays and hand them over to retail shopkeepers, who circulated them in rural and urban areas. A bookstore in Old Kanpur, Shrikrishna Pustakalaya, sold an estimated 75 million copies of nautanki script books until 1971, published by its printing press. It still publishes and sells hundreds of script books, several in their sixtieth or seventieth edition. To date, the repertoire of nautanki stories published as script books numbers over 400.[10]

Nautanki and the Anti-colonial Movement

A wide range of nautankis stimulated resistance to colonialism. Dramatist Vijay Pandit explains, ‘In North India, Nautanki was the foremost cultural medium to play a radical role during the national movement. Nautanki fought the battle in its own way: by enacting plays soaked in valour and patriotism throughout the length and breadth of Avadh, Purvanchal and Bundelkhand.’[11]

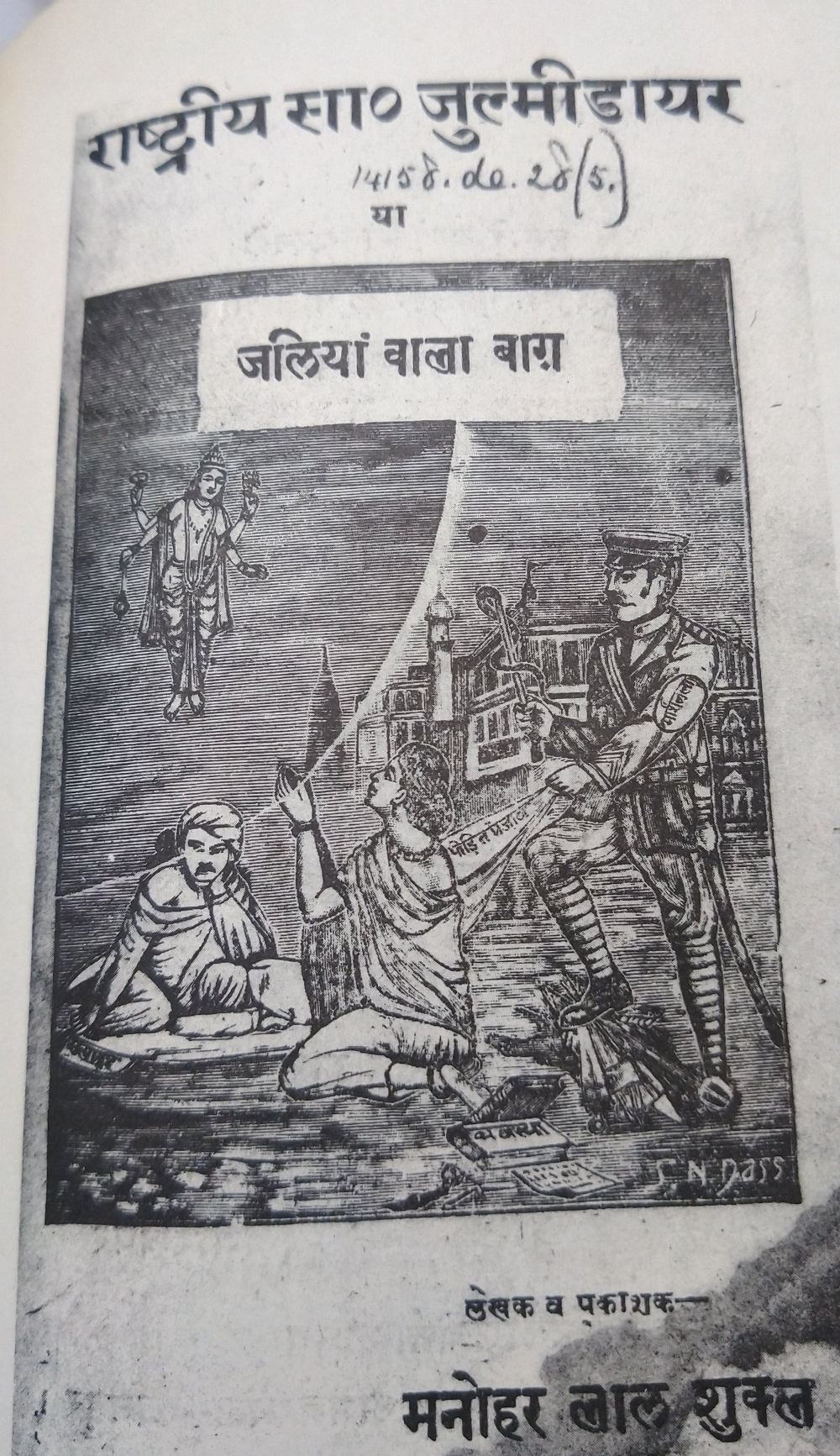

For instance, a nautanki called Rashtriya Saangit Julmi Dayar, written by Manoharlal Shukla in 1922, reconstructed the Jallianwala Bagh massacre from a child’s point of view, ending with the collective ghost of murdered citizens beating up General Dyer. (Fig. 3) Lal Babu of Aligarh composed Gandhi Haran in 1932, which inspired people towards civil disobedience; Munindra Nath Goswami of Lucknow wrote Balia Balidan, which presented the life of martyr Chittu Pandey and promoted Hindu-Muslim unity; Shrikrishna Pehelwan’s nautanki company presented Shaheed Bhagat Singh; Roopamji wrote Bangal ka Sher, Jawahar Jeevan, Abul Kalam Azad, Netaji and Rajendra Prasad Ji; and the nautanki Jhansi ki Rani Lakshmi Bai inspired women to participate actively in Gandhian campaigns.

Aurat ka Pyar was another powerful nautanki, designed to inspire patriotic feeling. (Fig. 4) In 1942, around the time of the Quit India campaign, Tirmohan Lal’s company performed this play at Kanpur’s Phool Bagh. A large crowd gathered to see the play and the city administration posted a posse of policemen to maintain law and order. In the play, a British police officer arrests the hero, a freedom fighter, and harasses the heroine, a young flower seller with strong nationalist leanings. Infuriated by the policeman’s insulting comments, the courageous heroine slaps him. The Phool Bagh audience responded to the heroine’s retaliation with loud clapping, and someone raised an anti-British slogan. Reacting to the situation, policemen jumped into action, stopped the show, and wielded lathis (batons) to disperse the crowd. Immediately thereafter, the city administration banned Tirmohan Lal’s company from Kanpur city, a ban which remained in effect right up to 1947. Tirmohan Lal and his troupe were undaunted: they shifted to Kannauj and continued rehearsing and performing all over, including countless shows of Aurat ka Pyar.[12]

![Fig. 4: Script books of Aurat ka Pyar urf Bahadur Ladki [A Woman’s Love, or Courageous Girl], a powerful nautanki that inspires patriotic feeling. Shrikrishna Pustakalaya, a bookstore in Old Kanpur, sold an estimated 75 million copies of nautanki script books until 1971, published by its printing press. It still publishes and sells hundreds of script books, several in their sixtieth or seventieth edition (Courtesy: Deepti Priya Mehrotra)](http://www.sahapedia.org/sites/default/files/styles/sp_inline_images/public/inline-images/4.Aurat%20ka%20Pyar%20urf%20Bahadur%20Ladki%2C%20-%20script%20book_0.jpg?itok=K4SklbkU)

A Syncretic Community of Artistes

Like the nautanki form itself, nautanki troupes drew from a mixed heritage and represented a plural culture. The social background of the artistes included a wide range of castes and creeds. Male artistes hailed from Muslim, Dalit, as well as middle and upper caste backgrounds. Women artistes were initially from traditional entertainer-singer backgrounds, predominantly the Bedia caste and Deredar Muslims. Later, however, women from various castes joined nautanki. Syncretic traditions flourished among this community of artistes; it was commonly accepted that kalakar ki koi jati nahin hoti (artistes are above sectarian affiliations).[13]

Comradely ties were fostered within a shared community life. Troupe members travelled together at a stretch for seven or eight months, from Janmashtami to Holi, taking a break during the harsh summer and monsoon season. Living in close quarters, artistes developed an intimate understanding of each other’s customs. They performed regularly at dargahs as well as Hindu shrines and festivals—for instance, at Makanpur during Madar Shah’s urs (death anniversary of a Sufi saint); Devi Paatan during Navaratri; Dargah Sharif, Bahraich, for Gazi Sarkar’s urs; Beeghapur during Shivratri; and Kashipur during Chait (a month in the Hindu lunar calendar, corresponding to March/April).

Hindu and Muslim artistes lived and ate together and respected each other’s beliefs. Nautanki actor Munni Bai recalls:

We kept a fast—Brihaspat vrat—once a week. During Saavan [a month in the Hindu calendar which coincides with July–August] we kept a fast in which we could eat only fruit. Muslims kept roza [religious fasting] for a month. The iftar [meal breaking the day’s fast] took place after dusk before the start of Nautanki at night. The morning meal was at 4 a.m., before sunrise. We would sing while they went backstage and ate bread with tea or milk, or roti and vegetable, smoked a bidi (leaf-wrapped cigarette), washed and read namaz. When their turn came, they would be on stage again.[14]

Everybody ate from the same kitchen, where usually a Brahmin pandit cooked the meals—dal, roti, rice, vegetables and chutney. Everybody brought their own plates and served themselves. If staff members wanted meat, fish or eggs, they pooled in money and cooked the dish in their rooms.

People in nautanki had fluid caste boundaries as compared to mainstream, particularly upper-caste, society; this was one reason why the upper-caste elite looked down upon nautanki. The stigma and vilification increased after women joined nautanki troupes. The public was crazy about many of the heroines, yet at the same time considered them beyond the pale of respectability.

Several women who joined nautanki became extremely popular actors, and, by the 1950s and 60s, set up their own nautanki companies. For instance, Gulab Bai set up the Great Gulab Theatre Company and Krishna Bai established the Krishna Nautanki Company; other eponymous troupes included Bimla Devi and Company, Sita Devi and Company and Mala-Chanchala’s Nautanki Company. Like other successful nautanki companies of the time, most of these companies owned elaborate props, costumes, musical instruments and moveable stage paraphernalia, all of which were transported to performance venues on trucks or buses.[15]

Nautanki artistes were adventurous people, heroes and heroines in their own right. Being part of travelling theatre, they were habituated to moving from place to place, setting up tents, only to fold and pack them a few days later. Often they walked a tightrope between hostile authorities and the law. On various occasions, the nautanki companies faced charges, threats or persecution, because of a particular play being considered obscene, or that it inspired people to revolt against the dominant political authorities. However, with the advent of cinema and television, nautanki faced enormous competition and could no longer hold its central position in the entertainment landscape.

Decline of the Art Form

Indian cinema bears many a debt to nautanki. Bollywood films in the early years borrowed plots, styles of song, dance and characterisation from nautanki and other popular theatre genres. Melodrama, music, the tension between evil and good, royal courts, bandits and jokers, side-heroes and side-heroines were imported from stage to screen. By the 1960s, cinema became the dominant medium of mass entertainment, and nautanki began to borrow from the cinema! While The nautankis Mughal-e-Azam and Jehangir ka Insaf were based on the 1960s Bollywood film Mughal-e-Azam, and Pukar, Sholay and Nagin were inspired by the films bearing the same titles.[16] Nautanki adapted costumes, songs and plots from popular films, and actors modelled themselves on well-known cine heroes and heroines.

By the last decade of the twentieth century, most nautanki companies had collapsed. Company owners lacked the capital to usher in new technologies and innovations. Companies languished, went bankrupt, shut down, or performed on an ad hoc basis, with no permanent staff and diminished work opportunities. Tens of thousands of artistes keen to perform good nautankis were no longer able to eke out a livelihood.

The government awarded the Sangeet Natak Akademi award to Shrikrishna Pehelwan in 1968 and Padma Shri to Gulab Bai in 1990 but did not lend sufficient support to the form itself. (Figs 5 and 6) The market for nautanki shifted from wholesome theatre to cinema as well as titillating entertainment on stage. Genuine performers who refused to submit to the trend grieve the decline and eclipse of good nautankis. They are embittered for as the veteran artiste from Mathura, Kamlesh Lata remarks, ‘If artistes live hand to mouth, finding it difficult to remain alive, can they keep the art alive? A musician too needs nutrition!’[17] Elderly artistes are keen to pass on their skills but the infrastructure to enable this is missing. There is no institutionalised training for young artistes nor support for rehearsals, performances and development of new scripts. Lack of formal education and training as well as social stigma and prejudice has made it difficult for most traditional nautanki artistes to survive. With little opportunity to exhibit their talents, they are fading into oblivion, living in slums and doing odd jobs to survive.

A new crop of performers plays to the market by performing sensuous dance sequences as nautanki. Some of these performers take on names such as Karishma, Shilpa and Priyanka, playing local substitutes for the Bollywood heroines. The populist dances they perform, at parties, weddings and other functions, are far from the traditional theatre form of nautanki. Kanpur-based ‘Dream Girl Shilpa’, for instance, holds ticketed shows, advertised as nautanki for packed halls in Mumbai, where she performs her dance numbers for a few hours, interspersed with one or two tiny excerpts from Laila Majnu, rendered by a couple of genuine, ageing, nautanki actors.[18]

Real nautankis have survived to an extent, far from the limelight, in places such as Hathras, Mathura, Unnao and Beeghapur, where a few troupes continue to perform traditional plays for a discerning audience.[19] Companies such as the Great Gulab Theatre Company and Krishna Kala Kendra perform occasionally, when invited to do so. (Figs 7 and 8). Actor Madhu Agarwal of the Great Gulab Theatre Company makes a fervent appeal: ‘The government should discriminate between real and spurious nautankis. Chaff is being sold as wheat—and at a higher price! The government should stop this. Spurious nautankis should be banned but real nautankis should be promoted.’[20] She reveals, on a more hopeful note, that there is of late a resurgence of interest in nautanki.

The Revival

At the turn of the century, Shehzadi Nautanki seemed to be on her deathbed; but today there are signs of revival. Agarwal says:

We are receiving invitations of late, from prestigious cultural institutions like Hindi Akademi, Delhi, and Sangeet Natak Akademi, Lucknow. In the past few years, we have performed Anarkali, Amar Singh Rathore, Dahiwali, Harishchandra Taramati, Sultana Daku and other Nautankis, at the behest of such organisations. People are realising the value of nautanki, writing books about it, trying to understand it better. This is leading to a revival of the form.[21]

Dramatist Siddheshwar Awasthi declares, ‘If Uttar Pradesh does not have nautanki, what will it have? If nautanki dies, there will be nothing of our own left!’[22] Awasthi and dramatists such as Urmil Thapliyal, Tripurari Sharma, Raj Kumar Shrivastava and Atul Yaduvanshi have tried to preserve and contemporise nautanki by incorporating it within modern theatrical productions, encouraging performances by traditional troupes and writing and producing new nautankis.[23] (Fig. 9) Nautanki plays are also widely circulated as CDs and DVDs and on the internet.

Hansen notes that nautanki, ‘once pronounced dead, [has] made a modest comeback of late’.[24] She links this to attempts by secular forces to reinvigorate India’s ‘composite culture’. A composite culture, implying ‘a shared, syncretistic aesthetic, and… a history of coexistence rather than antagonism along communal lines’ is particularly relevant today, to prevent Indian culture from being restricted to a majoritarian Hindutva version. Nautanki could well provide resources for refashioning popular culture and media along pluralistic lines. A play like Amar Singh Rathore, for instance, retells a true tale of cross-community friendship, loyalty and allegiance, and could thus be skillfully deployed ‘to defuse communal antagonism, accentuate amity, and espouse religious pluralism’.

Nautanki actor and scholar, Devendra Sharma notes that several agencies are using nautanki to spread social and health messages and finding it effective. He adds, ‘Nautanki… is an important communication tool for the illiterate and semi-literate people to have a community dialogue on their local social conditions with dignity.’[25] Sharma has worked with local communities in North India, producing new nautanki plays, and also with non-resident Indians in America, performing nautankis on contemporary concerns to appreciative audiences.

Thus, there is hope that nautanki will survive into the future, and flourish in multiple contexts.

Notes

[1] Salil, `Uttar Pradesh ki Loknatya,’ 15–18.

[2] de Bruin, ‘The Hybrid-Popular Theatre Movement and the Tamil Natakam Theatre.’

[3] Yaduvanshi, ‘Aaj Bhi Deevane Hain Nautanki Ke,’ 30.

[4] Agrawal, `Nautanki ka Uday,’ 51–52.

[5] Kamlesh Lata, in conversation with the author.

[6] Hansen, Grounds for Play, 220–25.

[7] Raghav, `Ek Thee Gulab,’ 32.

[8] Saxena, `Nautanki aur Lavani,’ 63.

[9] Hansen, Grounds for Play, 257.

[10] Ibid., 86–112.

[11] Pandit, Loknatya Nautanki, 3.

[12] Mehrotra, Gulab Bai, 105–12.

[13] Nargis, in conversation with the author.

[14] Munni Bai, in conversation with the author.

[15] Mehrotra, Gulab Bai, 190–94.

[16] Madhu Agarwal, in conversation with the author.

[17] Kapoor, `The Nautanki Theatre,’ 147.

[18] Shilpa, in conversation with the author.

[19] Chinha Guru, in conversation with the author.

[20] Madhu Agarwal, in conversation with the author.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Siddheshwar Awasthi, in conversation with the author.

[23] Shrivastava, ‘Nautanki ki Jeevantata,’ 60–66.

[24] Hansen, ‘Staging Composite Culture,’ 151–52.

[25] Sharma, ‘Nautanki Performances: Creating Sites for Community Connection and Social Action,’ 23–24.

Bibliography

Agrawal, Ram Narayan. ‘Nautanki ka Uday, Vikas aur Vartman Sthiti.’ In Loknatya Nautanki: Kuchh Prashn, edited by Rajendra Bahore and Vijay Pandit, 49–55. Lucknow: Uttar Pradesh Sangeet Natak Akademi, 2000.

de Bruin, Hanne M., ‘The Hybrid-Popular Theatre Movement and the Tamil Natakam Theatre.’ New Kolam: A Mirror of the Dravidian Culture 5–6, section IV (2000).

Hansen, Kathryn. Grounds for Play: The Nautanki Theatre of North India. New Delhi: Manohar, 1992.

———. ‘Staging Composite Culture: Nautanki and Parsi Theatre in Recent Revivals.’ South Asia Research 29, no. 2 (2009): 151–168. Accessed October 6, 2019. https://minio.la.utexas.edu/colaweb-prod/profile/custom_pages/0/119/staging_composite_culture_nautanki_and_p_59c4789f-7609-465a-9d2f-14fd967eed0e.pdf.

Kapoor, Shivani. ‘The Nautanki Theatre in Brij: Tales, Tradition and Beyond.’ M.A. thesis, Department of Journalism, Lady Shri Ram College, 2007.

Mehrotra, Deepti Priya. Gulab Bai: The Queen of Nautanki Theatre. New Delhi: Penguin, 2006.

Pandit, Vijay. ‘Loknatya Nautanki aur Bharatiya Svadheenta Andolan’ [Nautanki Folk Theatre and Indian Freedom Struggle]. Unpublished paper, 2003.

Raghav, Krishna. ‘Ek Thee Gulab’ [The One and Only Gulab]. Rang Prasang, Jan–June 2000: 19–42.

Salil, Suresh. `Uttar Pradesh ki Loknatya Parampara aur Nautanki.’ In Loknatya Nautanki: Kuchh Prashn, edited by Rajendra Bahore and Vijay Pandit, 15–24. Lucknow: Uttar Pradesh Sangeet Natak Akademi, 2000.

Saxena, Krishnamohan. ‘Nautanki aur Lavani.’ In Loknatya Nautanki: Kuchh Prashn, edited by Rajendra Bahore and Vijay Pandit, 61–71. Lucknow: Uttar Pradesh Sangeet Natak Akademi, 2000.

Sharma, Devendra, ‘Nautanki Performances: Creating Sites for Community Connection and Social Action.’ Paper presented at the conference, the Performance Studies Division, National Communication Association, San Antonio, Texas, 2007.

Shrivastava, Raj Kumar. ‘Nautanki ki Jeevantata keVaaste’ [So as to Keep Nautanki Alive]. Kala Vasudha, special issue on Nautanki (Sangeet) (Oct–Dec 2018): 60–66.

Yaduvanshi, Khemchand. ‘Aaj Bhi Deevane Hain Nautanki Ke’ [There Are Still People Crazy About Nautanki]. Kala Vasudha, special issue on Nautanki (Sangeet) (Oct–Dec 2018): 24–32.