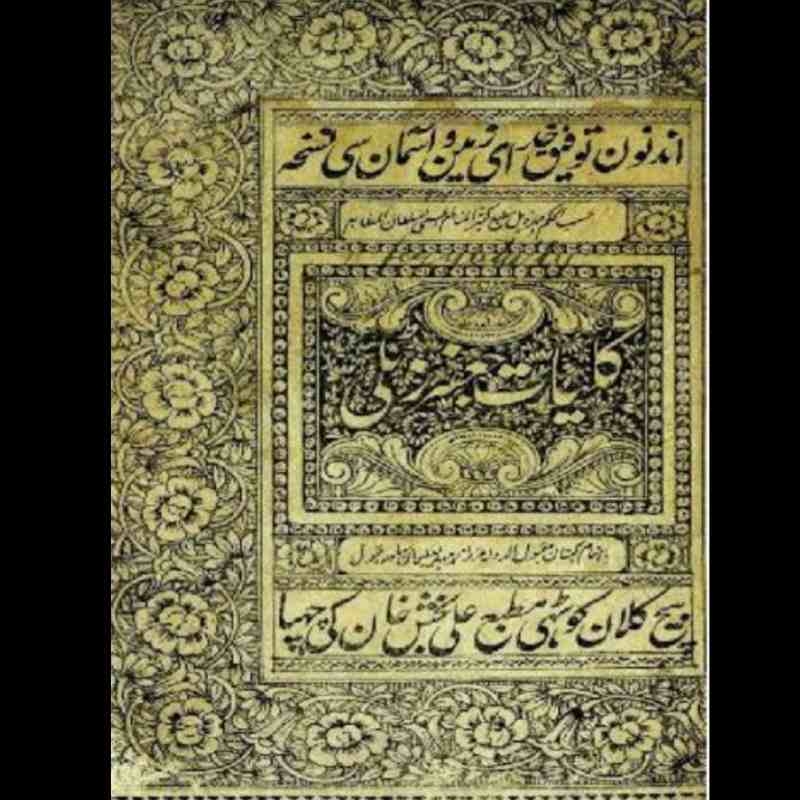

Choked to death with a shoelace for his poetry, Mir Ja’far Zatalli did not believe in sophisticated language and mincing words. Long ignored, we look at how Zatalli was a pioneer in creating a small but effective oeuvre of Urdu poetry and prose during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. (In Pic: Diwan - e - Mir Zatalli cover; Photo courtesy: IndoIslamicPage/Twitter)

Sikkae zadd bargandum wa moth wa matar

Baadshah hai tasma kash farrukh seer(The prevailing currency is of dal and peas

Because of the Emperor Farrukh Seer[1]

Is the one who kills people with his shoelace)

These were the lines that allegedly led to the death through tasma-kashi (choking through shoelace) of a much-ignored poet, Mir Ja’far Zatalli. It was a parody of the Emperor’s sikkah (the coins issued after the coronation of Emperor Farrukhsiyar in AD 1713/ 1125 AH), which originally read:

Sikka zad, az fazl-i Haq, bar sim o zar,

Pads hah-i bahr-o- bar, Farrukh-Siyar.(By the grace of the True God, struck coin on silver and gold.

The Emperor of land and sea, Farrukh-Siyar)[2]

Mir Muhammad Ja’far, who gave himself the pseudonym ‘Zatalli’ (meaning ‘babbler of nonsense’), was a late seventeenth–early eighteenth-century poet who pulled no punches when commenting on society and politics. Not shying away from accusing elites, kings and maulvis of acts of bestiality, homosexuality and murder, even while under their employment, it’s not surprising that it was one of his poems that led to his death.

Also read | The Presence of a Language: Journeys in Urdu Literature

Often regarded as the first Urdu satirist, Zatalli’s writings were filled with sexually explicit words and epithets—probably the reason for his being ignored or dismissed by modern scholars. He mixed Urdu and Persian, a language often referred to as ‘rekhta’ (meaning mixed, poured), in prose and poetry.[3] Urdu, the language of tehzeeb (sophistication) as we know it now, was still being formulated. As scholar Shamsur Rahman Faruqi says, ‘Doubtless, Persian with its great treasure house of the bawdy, the erotic, the pornographic, and the obscene, provided precedents of sorts. But there was no Persian writer who devoted himself exclusively to these modes.’ That was, until Zatalli.

Social Commentary

Mir Ja’far Zatalli was born to a Sayyid family—high caste Shia Muslims—in Narnaul (current-day Haryana), but the exact date of his birth is unknown. Neither is it known whether the choice of ‘Zatalli’ emanated from ‘the nonsense that he wrote’ or ‘as he was presumed by society’. Not much is known about his personal life either. ‘Zatalli may have remarried at the age of sixty, or he may have married two women at the same time at the age of sixty, if we accept as autobiographical a short poem in which he says precisely this: Ja’far, you spent your life in frivolities, and now at the age of sixty you have acquired two wives!’ says Faruqi.

His poetic presentation and expression present a fascinating and scandalous picture of Delhi’s social and cultural life towards the end of Aurangzeb’s reign (whom he extolled on multiple occasions), followed by his sons (Kam Baksh and Bahadur Shah I were especially trolled), and grandson Farrukhsiyar.

His ‘Wicked’ Humour

Zatalli used the hajju (lampooning) style of writing in his criticisms, many of which are available in the ‘Kulliat-i-Jafar Zatalli’. He did a hajju series of maulvis, princes, clergymen, government officials, elite families (including the women), and specifically Prince Kam Baksh, Mirza Zulfiqar Beg (the Kotwal of Delhi), Sabha Chand Khatri (an important functionary of Zulfiqar Khan, who was known for his sanctimonious ways, and also for his corruption). Zatalli combined the ‘personal’ with the ‘social’; his language crude and irreverent.

As a criticism of Prince Kam Baksh, he wrote of him practising bestiality:[4]

Zahe shah wala gaher kaam baksh

Ke ghachi burkard wa baksh(Well done, oh great king Kaambaksh

The little opening of the goat is ruptured into a gaping hole)

Zatalli also wrote an outrageous ‘Gandu-nama’ (a reference to sodomy) on the reign of Bahadur Shah I:

Hukm-e qazi, muhtasib za’il shude

dil badhakar gand marawwa kheliye

pir se aur baap se, ustad se

chhup-chhupakar gand marawwa kheliye

Author Raziuddin Aquil explains the couplet as exposing the extent of sexual transgressions by the king that occurred despite the presence of the qazis (Muslim judges) and muhtasibs (censor officials), whose powers were in decline (za’il shude). He points out how this was done, playfully, away from the gaze of (chhup-chhupakar) the father (baap), teacher (ustad) or the religious guide (pir).

Also read | Alternative Poetry of the Northeast

When Zulfiqar Khan became prime minister under Emperor Jahandar Shah, he left much of the state’s affairs to Sabha Chand, ‘Khatri, who was unique in wickedness and mischief, and passed his time in entertainment,’ writes Shahnawaz Khan.[5] Attacking Chand’s honesty, Zatalli wrote (translation by Faruqi):

‘Don’t be thinking anymore of fives and sevens

Lest the lining of your rectum come under pressure;

Beat the drum of truth at Court

Don’t strike a spark in a bale of hay;

Here, let my advice be stuck in your ears:

Say the bead of Ram’s name, keep to your senses.

In your bottom is a hole full generous,

Oh no, dear sir, it’s the hole for the flow of periodic blood;

Don’t threaten me with your master, the Khan,

Don’t be a smarty pants before me;

I am Ja’far, renowned for Nonsense,

I vault, I lay him prostrate and rip the backbiter’s arse.’[6]

Zatalli’s writings were like hardcore porn juxtaposed with the subtle elite poetry of the time. It may be surmised that his bold and explicit style might have been because of an antagonistic attitude towards society, and the state at large.

Ahead of his Time

There are two primary reasons that make Zatalli an important poet and literary personality of his time. First, he was one of the pioneers in combining the official Persian language with the chalti zubaan (colloquial language) of Delhi. His works freely mixed Persian to Hindi/Hindustani, laying the path for the origins of Urdu, thus reflecting the cultural and literary amalgamation of the period he lived in. Second, the poet’s death is testament to the power of his words and the impact it had. One can also say it set the stage for Urdu parody as a tool to make governments and people in general accountable. The very selection of his name undoubtedly reflects the image of both what goes on in society and yet what society would not like to talk about, and there was no-nonsense there.

This article was also published on The Week.

Notes

[1] Referring to Emperor Farrukhsiyar (r. 1713–19), who is said to have later ordered the execution of Zatalli, using a shoe lace.

[2] Ataullah, ‘Jafar Zatalli and the Historical Context’, Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 69 (2008), 447–54. Accessed June 9, 2020, https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/44147208.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A857763cfbce448c37939126474f42a0a.

[3] Raziuddin Aquil, ‘Jafar Zatalli: Exposing Fake Propriety of Those in Power’, Itihasnama.blogspot.com. Accessed June 9, 2020, http://itihasnama.blogspot.com/2019/03/jafar-zatalli-exposing-fake-propriety.html.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Shahnawaz Khan, Maasir-ul-Umara, edited by Mirza Ashraf Ali, Vol. I, pt. I (Kolkata: Asiatic Society of Bengal, 1888), 102–04.

[6] Shamsur Rahman Faruqi, ‘Burning Rage, Icy Scorn: The Poetry of Ja’far Zatalli,’ lecture under the auspices of the Hindi-Urdu Flagship, University of Texas at Austin, September 24, 2008. Accessed June 9, 2020, http://www.columbia.edu/itc/mealac/pritchett/00fwp/srf/srf_zatalli_2008.pdf.