My fascination with the history of Mumbai began when I joined Sir J.J. College of Architecture in 2012. As students, my friends and I would always look out for eateries which were not heavy on our pockets. That is when I first stumbled upon the iconic Irani cafes of Mumbai (then Bombay), which were famous for their maska (butter) buns and Irani chai. Years later, as an architecture graduate, I decided to document these fast-disappearing heritage eateries which form an important chapter in the evolution of Mumbai as a multicultural city.

The Irani cafes get their name from the Iranian people who migrated to India in the nineteenth and twentieth century. Though collectively termed Irani, they came from different regions of Iran at different periods. Many of them were Zoroastrians and, like the Parsis who also migrated to India from Iran earlier, were fleeing from persecution at the hands of Iran’s Muslim majority. There were non-Zoroastrian Iranis as well, who were trying to escape a severe famine that hit their country in 1870–72. Though Irani people just as the Parsis followed Zoroastrianism as their religion, they have a distinct culture and social status in India.

These difference exist because of various reasons including the fact that the Parsis arrived in India much earlier, from the tenth century onward, and deeply integrated themselves with the country’s political, social and business class over a millennium with their presence in banking, textile, shipbuilding and real-estate industries. Add to that, the Iranis spoke Dari, a dialect of Persian, and had arrived from Iran with very little capital. They had to build a new life from scratch; however, the hardworking Iranis soon found their feet in Bombay, a city that had always been welcoming to migrants.

The Irani migration to India continued till Independence in 1947. While many travelled by land, passing through Baluchistan, Sindh and Gujarat on the way, some came the way of the Arabian Sea. They settled in Bombay, Karachi, Pune, Hyderabad and other places on India’s western coast.

A significant majority of Iranis who settled in Bombay came from the cities of Yazd and Kerman in Central Iran. Yazd was already famous for its confectioneries, and the sweet-making skills of the immigrants brought them immediate success in their business in Bombay. Although low on money, luck favoured them because the corner plots on buildings were considered inauspicious by Indian businessmen, and were available at much lower prices. This is the reason why many old Irani cafes are located at intersections of streets.

The migration of the Iranis coincided with the dawn of the industrial revolution in India. Between 1860 to 1900, Bombay underwent rapid expansion and industrialisation. The railways had arrived in 1853 and the first cotton mill opened the following year. During the American Civil War (1861–65) high demand for cotton resulted in an explosion of new textile mills. Maritime trade with Europe was further bolstered by the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869. As the economy soared, the British government set up the Bombay Port Trust (1873) which constructed the Sassoon Dock in 1875, followed by two more wet docks in 1880 and 1888. These developments led to high labour demand and vast numbers of migrants started pouring into Bombay through the newly constructed Victoria Terminus which opened in 1888. This new class of labourers, mostly factory workers, railway workers and dock workers, became the core market for the Irani cafes which sold biscuits, bread and tea to them at very cheap prices. Depending on the location, the clientele also included naval officers and military personnel who were stationed at Bombay.

Before Independence, the Irani cafes were very popular with the European community, the Anglo-Indians, Indian Christians, Parsis and Jews, who ordered cakes and pastries during Christmas, Nowruz, birthday parties and weddings. At a time when public eating was highly segregated, the Iranian cafes welcomed one and all. As the Irani community prospered, they expanded their cuisine to suit their changing clientele and turned the cafes into larger restaurants. This ability to adapt has been a reason for the survival of the cafes for over a century.

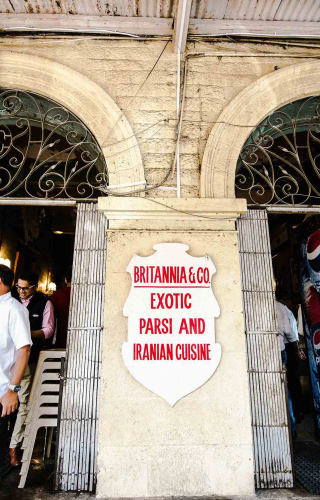

Britannia and Co. at Ballard Estate and Leopold Cafe at Colaba Causeway are keeping the Iranian cafe culture alive, but most of the smaller cafes are struggling to keep their business relevant in the age of app-based home delivery and competition from global fast-food giants. Other than the increasing competition, Irani cafes are closing down due to both economic and social factors. Apart from the cost of running the place (while keeping food quality high and prices low), the cafes have had to deal with harassment from the municipality over adherence to new safety rules and regulations. The eateries are located on prime real estate and, if sold, they can fetch astronomical prices for the owners. Thus, new opportunities and personal ambition of the new generation of Iranis are also reasons for the closure of some of the cafes. With an increase in social mobility and international travel, many Iranis either work in higher-paying jobs or emigrate to foreign countries, and see no point to engage with the family-run cafes in the future. The traditional cafe owners are either very old or dead now, with no one to fill their void. Over time, ownership has also changed hands, and although some Irani cafes have retained their old names, the current owners are perhaps no longer Iranis.

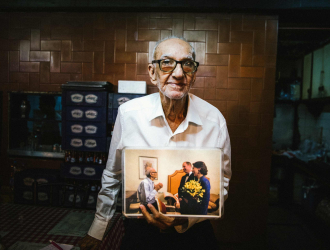

I focused my documentation on the smaller Irani cafes in Bombay. Mapping these structures was an eye-opener for me and I realised how the Iranian community has enriched the multicultural fabric of the city, not only through their cuisine but also through their Zoroastrian faith which is amply represented in the cafes. The cafes are not just restaurants, but cultural spaces where the Iranis have preserved their collective memories of Iran in the form of newspaper cuttings, flags, family photographs and vintage photographs of Persepolis, the ancient capital of Persia. While interacting with the owners, I became acquainted with the sheer tenacity that allows them to continue with the cafes and bakeries against all odds, and their deep love for the art of baking and serving their loyal clientele.

One needs to appreciate the Irani cafes while there is still a chance. Step in, grab a quaint corner, enjoy the bun maska dipped in chai and the other delicacies they have to offer. Maybe grab a flavoured soda or two and get submerged in the slow-paced Bombay of the seventies and eighties. If you have time on your hands, have a friendly chat with the proprietors of these cafes, who will entertain you with stories of the bygone eras. As you step out to leave, the nostalgia of olden times will beckon you, and I am sure you would want to come again, and again.