Rajasthan is shaped by conflict, either against nature or against foreign invaders. The harsh desert environment affected trade, agriculture and water resources, and constant warfare hindered the building of urban settlements, human migrations and expansion of territory. As a result, Rajasthan was divided into small kingdoms competing with each other for land, power and resources. Urban settlements were confined within walls of heavily fortified hilltop forts. However, the tenacious spirit of Rajputs prevailed over unfavourable circumstances and they managed to retain their freedom during much of Mughal rule and throughout the British Raj (except in Ajmer).

Their struggle is reflected in the history of Mewar, established by the legendary Bappa Rawal in the eighth century. As Northern and Western India came under waves of foreign invasions from the tenth century onwards, Mewar managed to remain independent. Their capital at Chittor was attacked several times, first by Alauddin Khilji in 1303, then by Bahadur Shah of Gujarat in 1535, and finally by Mughal Emperor Akbar in 1567–68. Each time the valiant Rajput men rode out to die in battle while their women and children committed Jauhar (self-immolation) rather than be taken captive.

Having lived through the fall of Chittor twice in a span of twenty years, Maharana Udai Singh II (r. 1540–1572) shifted to Gogunda and searched for a new site that was more defendable and closer to a large waterbody. In a dry state like Rajasthan, the availability of freshwater played a critical role in withstanding long sieges. He stumbled upon an artificial lake that had been created by Banjara tribes in 1362 CE. Surrounded by the Aravalli Hills, with thick forest cover and vantage lookout points, this lake became the nucleus of a new city which Udai Singh II named after himself, Udaipur. He undertook building a new palace by the lake, which got named Pichola, after a nearby village of the same name.

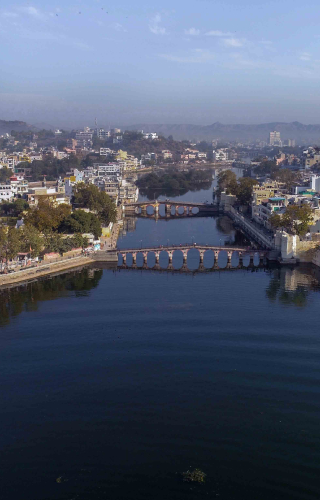

To prevent the lake from drying up, successive maharanas undertook dam construction and sophisticated water harvesting methods. Pichola expanded to a network of lakes, connected to each other through conduits and channels. These are Fateh Sagar, Swaroop Sagar, Rang Sagar and the smaller Doodh Talai lake. As the city expanded, the elite of Mewar built numerous palaces, havelis, gardens, pavilions, temples, ghats, shrines and gateways around these lakes. The palace started by Udai Singh II expanded, and successive generations added 11 new palaces to the original structure. This is now the City Palace, open to tourists as a museum and a much sought-after wedding venue of the haut monde.

The cool waters of the lake attracted Mewar royalty to build palaces on Pichola where they lived during the hot summer months. The first such palace is Jag Mandir, which was expanded by Maharana Karan Singh II (r. 1620–1628) and finally completed by Maharana Jagat Singh I (r. 1628–1652), after whom it was named Jagat Mandir. In 1623, Maharana Karan Singh II gave refuge to Prince Khurram (later Emperor Shah Jahan) and his family, who at that time was engaged in armed rebellion against his father, Mughal Emperor Jahangir. During the 1857 Sepoy Mutiny, Maharana Swaroop Singh gave refuge to Europeans fleeing from Neemuch and sheltered them at Jag Mandir.

Udaipur’s other, more famous water palace is the Lake Palace, formally known as Jag Niwas, built between 1743 and 1746 by Maharana Jagat Singh II (r. 1734–1751), after whom it was named. One of the first royal palaces to be converted to a heritage hotel in India, the Lake Palace has hosted the rich, powerful and famous from around the world. Former guests include Vivien Leigh, Queen Elizabeth of Britain, the Shah of Iran, the King of Nepal, and US First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy, to name a few. In 1971, Taj Hotels Resorts and Palaces took over the management of Jag Niwas and restored it to its past glory. The hotel was featured in the 1983 James Bond movie Octopussy, as the mysterious lair of the titular character Octopussy (played by Maud Adams), which brought Udaipur global fame.

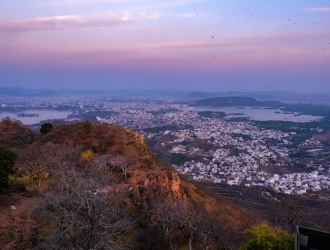

In Octopussy, another palace was featured as the hideout of the chief antagonist, Kamal Khan—the Sajjangarh Palace, located atop the Aravalli Hills. This palace was named after Maharana Sajjan Singh (r. 1874–1884). He had intended it to serve as an astronomical observatory but dropped the idea later. On completion in 1884, it served as a hunting lodge, offering a panoramic view of Udaipur city and its lakes. The palace overlooks Sajjangarh Wildlife Sanctuary, a forest reserve for reptiles, tigers, nilgai, sambhar deer, wild boars, hyenas, panthers and jackals. Because it was intended to observe monsoon clouds, it is popularly known as the Monsoon Palace.

Another vantage point overlooking Pichola Lake is Machla Magra, meaning Fish Hill. The Karni Mata Temple on top of the hill offers a panoramic view of Udaipur city. In the past this hill served as an observation post, and, during times of war, cannons were placed on the hill to fire at an approaching enemy. Crumbling old walls can still be seen on the way to the summit of Machla Magra, which is accessed via ropeway. Pichola Lake is surrounded on all sides by the Aravalli Hills, serves as an important nesting ground for a large variety of migratory birds.

Pichola’s most famous ghat is Gangaur Ghat, the venue of the eponymous Gangaur festival which takes place in March-April in celebration of Goddess Gauri, consort of Lord Shiva. Processions are taken out from the City Palace, passing through Udaipur, and ending at Gangaur Ghat. On normal days the ghat is popular with tourists and bird feeders who feed flocks of pigeons here. In the morning, citizens come for morning prayers, bathing or washing clothes. Unfortunately, the detergents and waste from these activities are degrading the water quality.

The deterioration of Udaipur’s lakes is a result of a massive spurt in tourism and the steady expansion of the city itself. Before the introduction of piped water, Udaipur’s lakes fulfilled the drinking water and freshwater requirements of its citizens, but its role in modern times is limited. Udaipur is a popular destination for both Indian and international tourists, and most of them prefer staying in hotels surrounding the lake. Dozens of lakeside hotels and restaurants, plus thousands of households collectively discharge tons of human waste and sewage directly into the lake. This has not only polluted the lake but also negatively impacted its flora and fauna. The lake once had a large population of crocodiles, but they were hunted to near extinction. Very rarely is one spotted nowadays.

Another threat to the lakes is siltation, which has accelerated due to mindless deforestation of the surrounding Aravalli Hills. The thick forest cover seen in old paintings and photographs is gone now. Each monsoon, rainwater washes away the topsoil and tonnes of silt get deposited in the lakes. This is slowly filling up the lakes, and in a hundred years they will be completely filled up if the Aravalli forest cover is not restored and steps aren’t taken to desilt the lake bed. The tourism industry, on which Udaipur’s economy is heavily dependent, will cease to exist if the lake turns into a cesspool, or worse, gets filled with silt. Udaipur and its lakes are intertwined in history like conjoined twins. One cannot exist without the other, and they cannot be separated. For Udaipur’s own future, Pichola and its sisters must be defended by the citizens of Mewar, the same way they defended their freedom.

This content has been created as part of a project partnered with the Royal Rajasthan Foundation, the social impact arm of Rajasthan Royals, to document the cultural heritage of the state of Rajasthan.