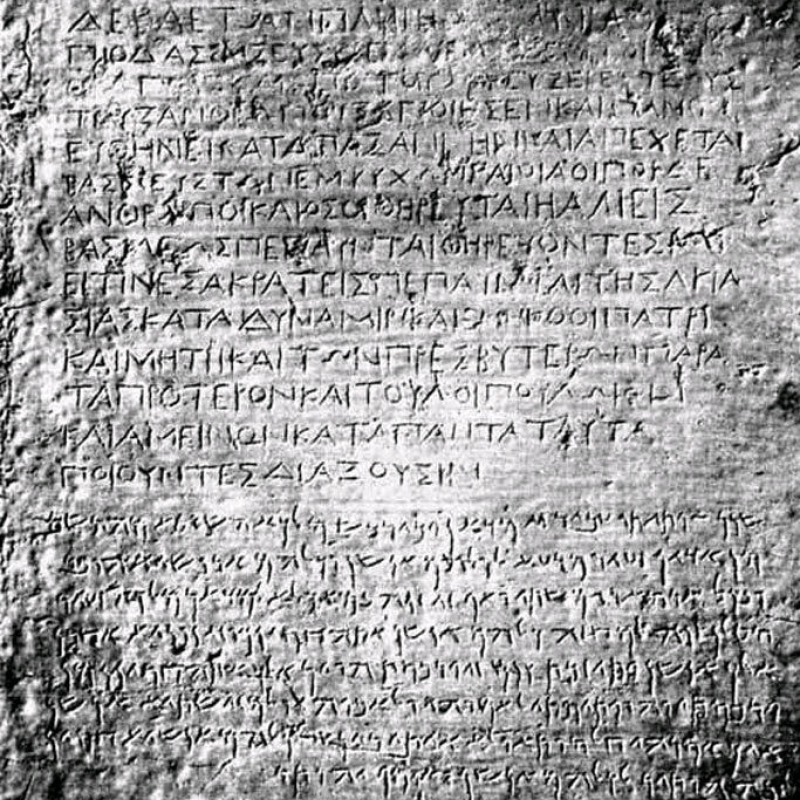

The huge corpus of epigraphic literature found from different parts of the Indian subcontinent forms a major source for understanding various aspects of early Indian society, religion, economy and culture, besides dynastic and political history. Epigraphic sources have been used extensively for reading early Indian history. More than one lakh inscriptions have been reported from the Indian subcontinent and the number is increasing as inscriptions are being discovered regularly.[1] One of the most interesting and unique genres of epigraphic records are literary inscriptions. The name itself reveals that the content is primarily literary. Though limited in number, literary inscriptions form a quite significant and unique source of valuable historical information, given that dramas and poems, the texts of which are otherwise unknown, have been discovered in the study of the same.

On stone we have three major dramas—Lalit Vigraharaja nataka and Harakeli nataka from Ajmer[2] and the Parijatamanjari natika or Vijayasri natika from Dhar.[3] Of these, the Parijatamanjari natika is mentioned by the poet as a prasasti (eulogy of a king by a court poet) of reigning Paramara king Arjunavarman (early thirteenth century CE), even though he himself mentions it as a natika (drama) as well.

Besides these dramas, we also have poetry on stone like the satakas (literally meaning 100 verses) engraved on the walls of the Bhojasala at Dhar in Madhya Pradesh.[4] However, scholars in the past had considered the Sitabenga inscription (c. third–second BCE, Chhattisgarh) as the earliest poem on stone, but recently the present author has shown that this was not poetry and neither can the site of the Ramgarh caves, which house the two caves Sitabenga and Jogimara, be considered an amphitheatre.[5] A peculiar character of the two satakas mentioned above is that the authorship of both have been assigned to the celebrated Paramara king, Bhoja (first half of the eleventh century CE). Bhoja shifted his capital from Ujjain to Dhara and it became a great centre of learning as Bhoja was a patron of littérateurs. Even if the first sataka may be attributed to him, the second one, i.e. the Avani Kurma sataka, was definitely not his composition as the tone of the second one praising Bhoja himself is unlikely to have been his own composition. Both the satakas begin with an invocation to Shiva. In the first sataka, Shiva is portrayed as Lord of Parvati. Pischel believed that the poems are dedicated to the kurma or tortoise incarnation of Vishnu.[6] But this is not the case as the verses clearly indicate that here the adikurma has been praised.[7] The satakas are important from the point of view of kurma symbolism and its development. Here, the kurma has been seen as the supporter of the earth, and the analogy is with the ruler who also supports the earth like the adikurma. In the second one, Shiva’s kankalamurti (skeleton form) has been praised. This form of Shiva is more popular in the southern part of the subcontinent, which might also indicate that the poet who conceptualised the opening verses in the second sataka probably hailed from South India. These two satakas have 109 verses each. As far as their literary value is concerned, these are not of a high order. There are other poems inscribed on stone which are also attributed to Bhoja and have been discovered from Dhar—Khaḍga sataka and Kodanda kavya; however, these could very well be works of his court poets. The language of these poems is Maharashtri Prakrit.

Apart from the dramas and poems discussed above we also have khandas and mahakavyas (epic poetry) engraved on stone such as the huge Rajaprasasti mahakavya of Ranachoda in twenty-four sargas (chapters) inscribed at Udaypur.[8] Though the Udaypur inscription is a mahakavya in form, it is primarily eulogistic and dedicatory in its content. However, there are a few other records which are not purely literary inscriptions but their literary value is unmistakable. D.B. Diskalkar considered some compositions which are no doubt important from a literary angle[9], such as the Junagarh prasasti of Rudradaman[10], Allahabad pillar inscription of Samudragupta[11] and the Aihole prasasti.[12] Along with this he also mentions a few others like the Dudhpani rock inscription of Udayamana (c. eighth century CE), known for its highly poetical value.[13]

The Parijatamanjari natika was engraved on a pair of stones of which one is lost. The play was composed by a poet who was also the royal preceptor or rajaguru named Madana alias Balasarasvati. It contains the story of Vijayasri or Parijatamanjari, princess of Gurjara and daughter of Jayasimha, and her love affair followed by marriage to Arjunavarman, a Paramara king, the defeater of her father. The play breaks off at the end of Act II. The rest of the play is probably on another slab which is missing. It may be possible to reconstruct it with the help of Sriharsha’s Ratnavali by which the author seems to have been highly influenced. However, Madana, the composer, claims, as was the trend, that his was a fresh composition. The characters in the play speak Sanskrit and Prakrit. The Prakrit passages in the play present a unique feature in that they are all in Sauraseni, even the prose passages, and not Maharashtri, thus a deviation from the regular norm. The theme of the drama belongs to the typical vasantotsava nataka genre, meant for live performance in the surasadana or hall or open space for performances in the temple of Goddess Sarada. The first act is named Vasantotsavah and the second act is named Tadanka darpana, i.e. the reflecting earring, in Prakrit. The play has a light-hearted theme with plenty of music and dalliances. The vasantotsava dramas have a more or less uniform theme wherein the chief male character hails from a royal background and is a dhiralalita type of hero—one who is relaxed, with the burden of royal duties delegated to an able minister, an expert in fine arts and the erotic. The heroine is a maiden who is of the ‘simple’ or mugdha type, hailing from a royal background as well, although her identity is not revealed till the climax. Polygamy is the norm in case of the hero, and the heroine is never the chief queen; their nuptial ties seem to be solemnised in secrecy, awaiting social approval. This approval finally comes from the chief queen who delves into a ploy to harm the heroine, but, finally, when she realises the royal descent of the heroine she herself awards due recognition to the union between her husband and the heroine. The chief queen here is of the jyestha (oldest) category of heroines. This model, advocated by most composers, is followed by Kalidasa in his Malavikagnimitra and by Sriharsa in his Priyadarsika and Ratnavali. It is also the theme of the Viddhasalabhanjika by Rajasekhara.

Epigraphic studies of the Parijatamanjari reveal that Madana mentions, at the very outset, that the inscription is incised on a set of two black stones, which clearly gives us a clue that the drama is incomplete, given only one of the slabs was discovered. However, the engraver creates confusion by signing off his name at the end of the first stone, therefore giving an impression that this is the end of the composition. Madana’s statement about the second stone at the beginning of the play thus helps us to assume that we have lost the second stone. Moreover, the play is named after the heroine, i.e. Parijatamanjari, which also means that at the end she will be victorious. Whereas at the end of Act II her position seems to be highly insecure, again a clue that the play doesn’t end there. The vasantotsava format helps us to assume the developments in the play. At the end of the fourth act, the play will end in a happy situation wherein the chief queen would solemnise the marriage between Arjunavarman, her husband, and Parijatamanjari, a princess. The audience, in this case, seems to be highly educated and erudite and well acquainted with the plays of this genre or else it would be difficult to enjoy the performance of such a play. It is also interesting to note that, given the use of both Sanskrit and different forms of Prakrit in the play, those who had gathered to experience this play were fluent in both languages. Though the second slab is lost, still the audience in history will enjoy this incomplete play for several reasons. Firstly, the archaeologists and future explorers can find the other pair of stone. Secondly, the two acts seem to be almost like a complete play, which is interesting, yet is incomplete as the author himself mentions that this was engraved on a pair of black stones. Thirdly, this helps us identify a pattern of vasantotsava natakas and also speculate what would be the other half of the story.

Two unique literary inscriptions of the early medieval period were found engraved on stones presently located in the Adhai-din-ka Jhonpra mosque, on the lower slope of the Taragarh Hill at Ajmer. The script is Nagari of twelfth century CE. These inscriptions contain portions of two hitherto unknown plays—one, Lalita Vigraharajanataka, which was composed in honour of the King Vigraharajadeva of Sakambhari by Mahakavi Somadeva, while the other, Harakeli nataka, composed by Vigraharajadeva himself.[14] Three stones bearing the text of the drama (Harakeli) have been found till now, which bear three acts, of which two are incomplete; only the fourth act has been found intact. Another stone bearing the first act was also discovered later. According to Natyasastra, nataka usually has five-ten acts or episodes. Hence, it may be deduced that a major portion of this drama has been lost. Kielhorn mentions the name of Princess Desaladevi as the principal female character of the drama. On the basis of the third and fourth act, the story of the play can be reconstructed. Like Parijatamanjari this play too is in the form of a prasasti of Chahamana king Vigraharajadeva, also addressed as Sakambharisvara.

The Harakeli nataka is also incomplete and only the name of the second act (not the act), Lingodbhava, and the almost complete fifth and the last act, Kraubchavijaya, is found engraved. That this was the last act of the drama is proved by the concluding statement: ‘Harakeli natakam samaptam’ (end of the Harakeli drama). It was also engraved by Bhaskara. It is distinctly mentioned as a composition of maharajadhiraja and paramesvara, the illustrious Vigraharajadeva of Sakambhari (line 37). It opens with a conversation between Shiva and Gauri. Other characters include Vidusaka, Arjuna, Muka and Pratihara. Vigraharaja praises his own creation by putting the words in Shiva’s mouth, who tells Gauri that Vigraharaja has so delighted him with his Harakeli nataka that they must see him too. Vigraharaja then enters and speaks in favour of his composition, and then the Lord assures him that his fame as a poet will last forever. Shiva then sends Vigraharaja to rule his kingdom of Sakambhari, and Shiva with his attendants proceeds for Kailasa. We may also assume that the character of Vigraharaja could have been played by the king himself. This drama has the reflections of Bharavi’s Kiratarjuniyam in portions; it also draws upon the Mahabharata. Vigraharaja also tried to emulate Paramara Bhoja and match him in literary creations.

In the case of these dramas, we find the composers resonating previous dramas. This is a way of claiming legitimacy or displaying their well-read status. For example, Parijatamanjari resonates with Ratnavali of Sriharsha, and Act III of Lalita Vigraharaja resonates with a sequence of Vasavadatta of Subandhu. Here, the principal character of the play is none other than Vigraharaja IV. Bhaskara, the engraver, is credited with the incision of another inscription of Vigraharaja Visaladeva which mentions 1210 Vikrama Samvat, i.e. 1153 CE. Bhaskara’s genealogy is also quite interesting. He is mentioned as the son of Mahipati and grandson of learned Govinda, who was born in a family of Huna princes and was, on account of his manifold excellences, a favourite of King Bhoja. Engraver Bhaskara provides his genealogy from his grandfather Govinda and also tries to flaunt the connection with Bhoja, who is hailed as an ideal and iconic ruler.

For the female characters, particularly Sasiprabha, the composer has used Sauraseni and Magadhi Prakrit. It is interesting to note that for the Turushka prisoners and spies the composer uses Magadhi, an eastern variety of Prakrit. In Sanskrit plays where both Sanskrit and Prakrit have been used, usually the king and elite male speak in Sanskrit and rest in Prakrit, while female characters would always speak Prakrit. This drama provides interesting insights into the espionage system of the early medieval times and the role of the duta or the envoy.

Again, many of the dramas engraved on stone were discovered in mosques, such as the Parijatamanjari natika found at the Kamal Maula mosque, and the Lalita Vigraharaja nataka and Harakeli nataka, discovered at the Adhai-din-ka Jhonpra mosque. However, the Kamal Maula mosque at Dharwas was earlier a Jain temple, and Adhai-din-ka Jhonpra was a brahmanical temple. Again, an inscription of Ajayaraja found from the Adhai-din-ka Jhonpra mosque also suggests that it was a Vishṇu temple which was turned into a mosque by Qutbuddin Aibak. All these temples were large and spacious with sadanas for enacting plays and hence suitable to be turned into mosques for performing the Friday mass prayers.

The selection of stone as a medium for engraving of such dramas is quite interesting. This was not an easy task. The length of the literary works was the biggest hurdle in the way of them being turned into epigraphic texts. Yet the patron opted for this medium only for the sake of seeking immortality for his composition. The composer seems to have been often aware that his text was meant to be engraved on stone; hence, he had to keep in mind the compactness of his text at the time of the composition. This is also likely to have affected the quality and style of the literary piece. It is also possible that those who were acquainted with stone as a medium had decided to experiment with the literary genre, and this was the reason for the relatively inferior quality of these engraved literary creations. Often these inscriptions were prasastis and this style gained popularity only in this central zone around Dhar or ancient Dhara. In and around this place, we also find the varna-naga-kripanikas or the sarpabandha inscriptions which are cryptic formulas for learning grammar. Thus, the temple complexes, which were the sites of these engraved literary pieces, functioned as hubs of learning grammar and literature. These subjects evidently generated interest among the literate urbane people in and around Dhar, if not in the whole of Malwa region. Such inscriptions are also reported from Un (Madhya Pradesh).

The study of such literary creations on stone is imperative to understand the actual activities that went on in the society. Language and themes of the dramas also help us to understand the mind of the early medieval audience and what the trends were in contemporary culture. The permanency or the perpetuity of the record reflects the wish of the composers to make them and their patrons immortal and their compositions ageless by engraving them on stones. However, as far as the literary quality or standard of such works are concerned, these are far inferior to the compositions of the littérateurs who composed and documented their creations on palm leaves, birch barks or even passed them on orally.

Notes

[1] Sircar, Indian Epigraphy; Saloman, Indian Epigraphy.

[2] Hultzsch, ‘Sanskrit plays in inscriptions at Ajmer.’

[3] Hultzsch, ‘Dhar Prasasti of Arjunavarman.’

[4] Disalkar, ‘Indian Epigraphical Literature.’

[5] Majumdar and Bajpai, Select Early Historic Inscriptions.

[6] Pischel, Epigraphia Indica.

[7] Kulkarni, trans, Kūrmaśatakadvayam.

[8] Chakravarti and Chhabra, ‘Rajaprasasti Inscription of Udaypur.’

[9] Disalkar, “The influence of Classical Poets on the Inscriptional Poets.’

[10] Kielhorn, ‘Junagarh Rock Inscription of Rudradaman I’; Sircar, Junāgarḥ Rock Inscription of Rudradāman I.

[11] Bhandarkar, Gai, Chhabra and Fleet, Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum.

[12] Sircar, Select Inscriptions Bearing on Indian History and Civilization.

[13] Kielhorn, ‘Dudhpani Inscription of Udayamana.’

[14] Hultzsch, ‘Sanskrit plays in inscriptions at Ajmer.’

Bibliography

Basu Majumdar, Susmita, and Shivakant Bajpai. Select Early Historic Inscriptions: Epigraphic Perspectives on the Ancient Past of Chhattisgarh. Raipur: Shatakshi Prakashan, 2015.

Bhandarkar, D.R., G.S. Gai, B. Ch. Chhabra, and J.H. Fleet. Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum III. Ootacamund: Archaeological Survey of India, 1981.

Chakravarti, N.P., and B. Ch. Chhabra. ‘Rajaprasasti Inscription of Udaypur.’ Epigraphia Indica XXIX (1951–52): appendix, 1–80.

Disalkar, D.B. ‘Indian Epigraphical Literature.’ Journal of Indian History XXXVII (1959): 319–39.

Disalkar, D.B. ‘The influence of Classical Poets on the Inscriptional Poets.’ Journal of Indian History XXXVIII (1960): 285–302.

Epigraphia Indica VIII (1905–06): 96, 241–60.

Hultzsch, E. ‘Dhar Prasasti of Arjunavarman: Parijatamanjari-natika by Madana.’ Epigraphia Indica VIII (1905–06): 96–122.

Hultzsch, E. ‘Sanskrit plays in inscriptions at Ajmer.’ Indian Antiquary XX (1891): 201–12.

Hultzsch, E. ‘Sanskrit plays in inscriptions at Ajmer.’ Indian Antiquary XX (1891): 201–12.

Kielhorn, F. ‘Dudhpani Inscription of Udayamana.’ Epigraphia Indica II (1894): 384–88.

Kielhorn, F. ‘Junagarh Rock Inscription of Rudradaman I.’ Epigraphia Indica VIII (1905–06): 36–49

Kulkarni, V.M. trans. Kūrmaśatakadvayam. Ahmedabad: L.D. Institute of Indology, 2003.

Saloman, Richard. Indian Epigraphy. New Delhi: Manohar, 1998.

Sircar, D.C. Indian Epigraphy. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 1965.

Sircar, D.C. Junāgarḥ Rock Inscription of Rudradāman I, (Śaka) year 72, A.D. 150. Kolkata: University of Calcutta, 1965. 169–74.

Sircar, D.C. Select Inscriptions Bearing on Indian History and Civilization II. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 1983.