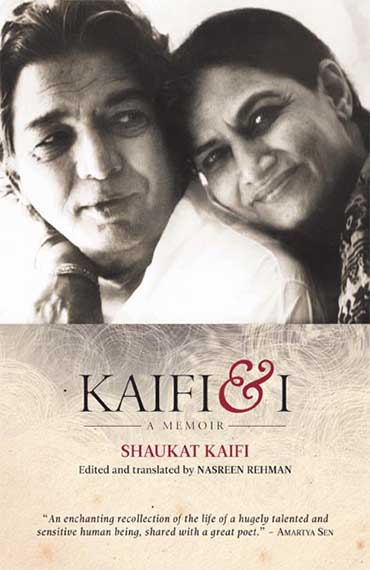

From the heart of a well-known family of Hyderabad to life in a single room with the barest of necessities, Shaukat Kaifi’s memoir of her life with the renowned poet Kaifi Azmi speaks of love and commitment. A marriage of over a half a century, a life steeped in poetry and progressive politics, continuing involvement with the Indian People’s Theatre Association, the Progressive Writers Association, Prithvi Theatre...all of these and more inform this beautifully told tale of love. Shaukat Kaifi’s writing details life in a communist commune, a long career in theatre and film and a life spent bringing up her two children, cinematographer Baba Azmi and actor Shabana Azmi. Nasreen Rehman’s deft and fluent translation brings this luminous memoir alive with warmth and empathy. ‘To say that this is a lovely book would be an understatement. It is an enchanting recollection of the life of a hugely talented and sensitive human being, shared with a great poet.’ — Amartya Sen. (Photo courtesy: Zubaan Books)

Here we have an edited excerpt from Shaukat Kaifi's memoir, where she recounts the time Kaifi Azmi—upset at not having her from her in quite a while during their courtship—wrote to her in his blood. What followed next is the stuff epic romances are made of.

Twenty days passed and Kaifi did not hear from me. He assumed that I was upset about something he might have written. Kaifi wrote to me in his blood.

21 March, Night. 1 a.m.

After I finished writing to you I sealed the envelope and went to bed thinking I might get some sleep, but could not. I re-read your letter and was unable to control my tears. Shaukat, it is my misfortune that you have no faith in me or in my love. For days I have been thinking of nothing but ways of trying to convince you that I love you. I have taken a blade and cut a deep wound into my wrist and now I am writing to you in my blood. For months I have shed tears for our love and now I am shedding my blood. I do not know what the future holds for us.

Moti, he continued, addressing me by the name I was called by my family, I am deeply hurt. How could you write, “Now I know that his eyes are not on me but on someone else who does not understand him; nor does she want to understand him”? Take back these words, Shaukat, and do not mock my love. If you cannot do anything for me, so be it. Even as I started loving you, I knew there was no hope. God will look after me. You question my love and my intention to marry you. All I can say is that one day, I shall prove myself to you and to the world.

My Shuakat, what is to become of me and of my love? We are so far away from each other that it is impossible for you to see the [sic] my pain. You believe what others have to say without trying to understand my compulsions. If I have said anything to upset you, please forgive me.

Lots and lots of love,

Yours Kaifi

To this day I have the letter. When I read it my head began to reel. I decided that the time had come for me to do some plain speaking. I took the letter to Abbajan, and declared that I would marry none other than Kaifi.

Abbajan, who was first and foremost a friend to all his children, read Kaifi’s letter, smiled and said, ‘Betey, a poet has a way with words that can sound terribly romantic but it is hardly wise to take him seriously. He may well be lying under the shade of a tree, enjoying the gentle breeze, as he claims, “I am hitting my head against a wall in agony and am writing to you in my blood,” as he dips his pen in the blood of a goat! Let us wait and watch.’

When Kaifi did not hear from me he was miserable and wept inconsolably. Everyone in the Party felt his pain. Comrade Mirza Ashfaq Beg, a lawyer who, apart from being a Party wholetimer, also worked with the English newspaper The New Age, decided to intervene. He appealed to P.C. Joshi, the General Secretary of the Party and it was with official approval that Comrade Beg arrived in Aurangabad and presented himself at Abbajan’s office, as a C.I.D. (Criminal Investigation Division) officer, who had come from Delhi, especially to meet Yahya Khan. Abbajan had him ushered in immediately. In time, Comrade Beg revealed his true identity. I do not know what transpired between them, but I do know that Abbajan came home and asked Ammajan, ‘Please, lay on a special meal as I have an important guest with me.’ Mirza Ashfaq Beg did not give up till he had convinced Abbajan that there was some merit in my marrying Kaifi.

That same night, I am told that Abbajan said to Ammajan, ‘Bibi, it is unlikely that you and I shall live forever. If we get Moti married to some boy she does not care for, then within three months of the wedding she will return home. And when you and I are no longer around, what will become of her? Who will look after her? But if we marry her off to Kaifi , she will have to assume responsibility for her choice: make or break, she will not be able to blame us and will have to live her own life.’ Ammajan heard him out silently but did not respond.

Also see | Ocean in a Goblet: The Songs of K.A. Abbas’ Films

Later that evening Abbajan spoke to me in confidence, ‘I am taking you to Bombay without telling your mother and siblings. Once you have seen their lifestyle for yourself, you will have to make your own decision. If you decide that is how you would like to live your life, I shall get you married off without consulting anybody.’ I was delirious with joy and rushed off to pack my suitcase. Abbajan explained to the family, ‘Moti is very distraught these days; I am taking her along on tour; it will give her an opportunity to think in peace about what is good for her.’

When Abbajan went on tour a mobile kitchen accompanied him in the shape of an innovative trunk. It opened out as a small cupboard with shelves for all the spices, lentils, rice, other dry rations and the kitchen utensils. Ammajan wanted to send the trunk with Abbajan, but he stopped her, saying ‘There is no need for it because we shall be back in a couple of days.’ The peon had bought our train tickets for Bombay. As I stepped out of my childhood home, I looked at it tearfully, as I said under my breath, Khush raho ahl-e-chaman ham to safar kar chale (Keep well, people of my land, for I must travel.)

Excerpt reproduced from Shaukat's Azmi's memoir Kaifi & I, published by Zubaan Books with the permission of the publisher.