The advent of Jainism in Kerala was earlier believed to be in the medieval period. However, an archaeological excavation in 2011 at Pattanam in Ernakulam district unearthed a Tamil-Brahmi-inscribed potsherd on which is inscribed ‘amana’,[1] a term used to refer to Jain monks. This new evidence suggests that Kerala had some contact with people who followed Jainism and the Jain faith must have been known to the inhabitants in the early centuries of the Common Era. The number of Jain temples dating to the medieval period (ninth century to thirteenth century) suggests that Jain settlements might have begun to appear then.

Jain temples from the medieval period can be seen in different parts of Kerala, with the major centres being Kasaragod, Wayanad, Palakkad, Kozhikode and Ernakulam. These temples are called ‘basadis’ and can be architecturally divided into two types—rock-shelter/cut basadis and mandapa-line basadis.

The basadi located at Kallil in Ernakulam district belongs to the rock-shelter type, where the shrine is built under an overhanging boulder. All other Jain temples of Kerala belong to the mandapa-line type. The Kallil temple was converted into a Bhagavathi temple in subsequent times. Many other Jain temples were converted into Hindu temples, including the Pallibhagavathi temple in Palakkad district.

The basadis in Kerala fall under two categories considering their main function: temples for the general public and as domestic basadis. For instance, the Parswanatha basadi located at Hosangadi, Manjeshwar, in Kasargod (see Figs 1 and 2) is a domestic basadi, which means it is located in a private residence.

In this article, we will focus on two basadis in Wayanad district of Kerala. The sculptural detail of these temples makes them distinct from the other Jain basadis of Kerala. These temples are referred to in historical literature as Janardhanagudi and Vishnugudi.[2] M.R. Raghava Varier, however, says that these names have a more recent origin.[3] The local people are not familiar with the names Janardhangudi and Vishnugudi and these temples are known as kallambalam (stone temples) among the local inhabitants; this strengthens the view expressed by Varier. The main idols of these temples are missing and we don’t know to whom the temples were dedicated. As the temples were abandoned a long time ago, we cannot ascertain their original status or purpose—were they public or domestic basadis?

Janardhanagudi

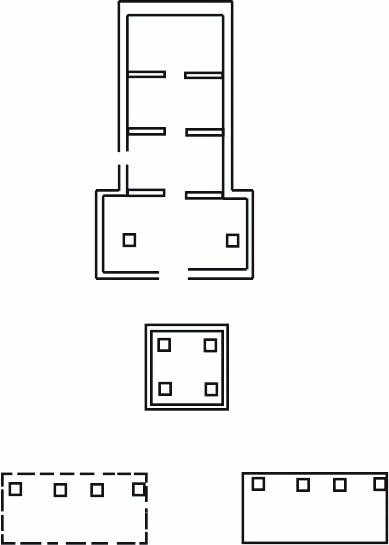

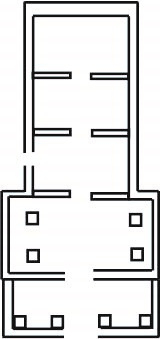

The temple complex has three components: sanctum, porch and gateway (see Figs 3 and 4).

These structures are aligned along a straight line (see Sketch 1).

The Janardhanagudi basadi is about a kilometre from Punchavayal junction and on the road to Neeruvaram. One enters the basadi through a gateway made of granite slabs—only the right part of this remains; the structure on the left has crumbled. The wall is carved with several sculptures. Garuda is sculpted as a dwarapala (door keeper) on the right gateway; he holds a snake in his left claw and snakes wind around his body. A monkey worshipping a linga is carved near this. Apart from these sculptures there are carvings of a tortoise and nagakettu on the front wall of the gateway (nagakettu refers to an intertwined knot of snakes or naga, see Fig. 5).

The base of the gateway is carved with tuskers, two monkeys sitting back to back, and also human figurines, including a snake-charmer playing his makudi (a reed instrument) to a snake. The exterior of the side wall also has carvings but these have been defaced. The gateway leads into a hall with two open sides and four pillars, each carved with beautiful sculptures including Vishnu, Muralidharakrisna, Krishna stealing Gopika’s garments, as well as salabhanjikas (sculpture of a woman standing near a tree or holding a branch), erotic scenes, possibly a seated Jina, a lady holding a parrot (Fig. 6), a monkey and a parrot.

A detached porch-like structure is located between the gateway and sanctum. It has a rectangular platform, and its ceiling is positioned on four pillars, one in each of the four corners of the platform. The pillar and the basement of the platform have beautifully carved figures. Each pillar has 12 figures with three carved on each face of the pillar. The figures include Vishnu in his matsya and kurma forms, Girija-Narasimha, Narasimha killing Hiranyakashipu, Ganesha, Garuda, a salabhanjika, devotees in anjali mudra, kalasa, a lady looking into a mirror while applying makeup, musicians and a seated monkey.

The sanctum is located after the porch and stairs with balustrades lead into the sanctum. The balustrades are carved with lion figures. Hanuman and Garuda are carved as dwarapala (doorkeepers) on both sides of the entrance wall. There are other sculptures on the front walls, including Kaliyamarddana Krishna, erotic scenes, a devotee in anjali mudra, male and female figures, a horse rider and floral motifs. The lintel above the entrance is carved with a Lakshmi figure. The sanctum has four cells. The first cell as one enters has two pillars with a set of three figures carved on every face, totalling to 24 figures. The figures on the pillars includes kinnaras (celestial musicians), elephant, lion, peacock, devotees in anjali mudra and floral motifs. In the second cell, both sides of the entrance wall are carved with Jaya and Vijaya[4] as dwarapala. A flight of steps leads into this. The entrance wall to the third cell also has sculptures of Jaya and Vijaya as dwarapala. On the left side, a Kannada inscription is engraved just above the dwarapala. The inscription records the offerings made by Devesan Janardhanadevar.[5] The position of the water chute indicates that the main idol was installed in the fourth cell.

Vishnugudi

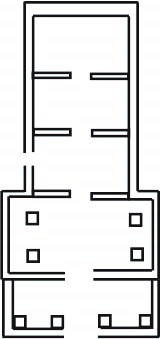

The Vishnugudi Jain basadi is at Puthangadi and lies about half a kilometre from the Punchavayal junction. Only the sanctum remains of the original temple. The dilapidated base and stone slabs indicate the basadi may once have had various structures built around it as in Janardhangudi. The outer plan of the sanctum is similar to the outer plan of Janardhangudibasadi (Figs 7 and 8), but the interior has a slight variation (Sketch 2).

Here, one can enter the sanctum through an attached porch with four pillars. These pillars are carved with various figures, including Girija-Narasimha, dancing figures, floral motifs and a monkey. The remaining structure of the basadi is the same as in Janardhangudi. Hanuman and Garuda are carved as dwarapala on the side of the entrance leading into the first cell. Unlike the two cells in Janardhangudi, this basadi has four upright pillars in the first cell and each pillar has three figures carved onto each side. The sculptures on the pillars include kinnara (Fig. 9), devotees in anjali mudra (Fig. 10), Ganesha (Fig. 11), Garuda, Gajalakshmi (Fig. 12), a parrot rider (Fig. 13), salabhanjikas, a female chauri bearer, lion, peacock and floral motifs. Jaya and Vijaya are carved on the sides of the entrance to the second and third cell. This cell has an entrance on its left side. The main idol must have been installed in the fourth as indicated by the position of the pranala or water chute (Fig. 14); the idol is missing now.

Both Vishnugudi and Janardhanagudi basadis are recorded as Vishnu temples in many reports.[6] This is due to the representation of Vishnu’s incarnations on the walls of the basadi, though representations of Hindu gods and goddesses are common in many Jain basadis. The famous Parswanatha Jain temple at Khajuraho has representations of Vaishnavite themes on the outer walls. The Hindu themes in Jain temples are a result of adaptations over time.

The architecture of these temples confirms they are Jain basadis. The plans of these temples are unique to the Jain basadis of Kerala—such plans do not occur in the Hindu temples of Kerala. Further, there are Jain temples in Karnataka which follow the same pattern of architecture.

Notes

[1] The Hindu, 'Tamil-Brahmi script found at Pattanam in Kerala.'

[2] Jhony O.K, Wayanad Rekhakal.

[3] Varier, Jainamatam Keralathil, 46.

[4] They are yakshas, considered as celestial beings in Jainism.

[5] Ibid.

[6] The Hindu, 'Vishnu temple in Wayanad now a national monument.'

Bibliography

Manoj, E.M. 'Vishnu temple in Wayanad now a national monument.' The Hindu, Kalpetta, September 11, 2015.

O.K., Jhony. Wayanad Rekhakal: Praadesika Charithram. Kozhikode: Mathrubhumi Books, 2010.

Raghava Varier, M.R. Jainamatam Keralathil. Kottayam: SPCS, 2012

Subramanian, T.S. 'Tamil-Brahmi script found at Pattanam in Kerala.' The Hindu, Chennai, March 14, 2011.