A hundred years ago, when the fascination with evolution was as its peak, scientists put forward the idea that the general reverence by humans for trees and forests harks back to a subconscious memory of arboreal existence. It was suggested that the unreasonable fear of storms, high winds and reptiles, as well as a desire to communicate with plants, links back to our days as primates. Since then studies in religion and anthropology have advanced a great deal, and there is now a more nuanced perspective on why groves and trees are universally deemed as sacred, why they tug at our heartstrings, and why they form a silent and strong bond between humans and the earth.

At a very elemental level, trees represent life or, rather, the regeneration of life. They leaf, blossom, flower and fruit in an unchanging, reassuring, seasonal rhythm. Their roots reach deep and connect the sky to the earth. Both classical and folk religion, which are deeply intertwined in India, consider the tree as purusha, or the male principle, which joins with the earth or prakriti, which is the female principle, seen in the rising sap or waters. This union creates life.

In Rajasthan, as elsewhere in India, folk beliefs and practices were assimilated into formal Brahmanical practice. Local, rural deities of groves and ponds became fused with the Puranic pantheon, to create a general vocabulary of divinity and ritual. So trees were worshipped both in the village grove and in the royal garden. While some trees like the banyan and the pipal enjoy a pan-Indian esteem, others like the shami or khejari are especially revered in Rajasthan.

Aside from their divine connotations, trees have an emotive pull, particularly in a land parched of vegetation. Their shade shelters travellers, wandering sages, poets and bards, and the odd, misplaced spirit. They feature in songs and folk tales filled with lament, longing and lust. Art always reflects life, and the prickly branches of thorn trees are seen in wall decorations and distinctive block prints of the Thar, while the rocky landscape dominates the unique Marwar court paintings. This essay highlights some of the distinctive ways in which the sparse vegetation of the Thar is incorporated into daily life and rituals.

The Khejari

Certain trees have a pan-Indian significance, as they are integral to the Vedic/Brahmanical form of Hindu worship. Prominent among these are the banyan, pipal, mango, kadamba and amla. In addition to these trees, in Rajasthan, a special pride of place among sacred trees goes to the khejari or the Indian mesquite (Prosopis cineraria). This is a medium-sized evergreen tree, with prickly branches, a small spreading crown and deep roots. It is ideally suited to the arid climate, and its wood, fruit and bark are indispensable to the sustenance of the community. (Figs 1 & 2)

Fig 1 & 2 : Khejari tree with fruit pods (Photos by Malini Saigal)

For the Hindu tradition, the khejari tree contains the sacred fire. The Vedas refer to fire being created out of rubbing two twigs, one from an ashvattha tree (pipal) and the other from the shami (khejari). The latter is said to contain fire in its belly (or garbha/hollow) (Doniger:300). Legend has it that the vedic deity Agni was asked by the gods to take on the role of carrying the sacred oblations from the yagna to them. However, Agni did not just refuse the request, but he also hid from place to place to avoid any discussion. He first hid in an ashvatta tree, where an elephant soon spotted him. Then he disappeared inside a bamboo near a river, but was betrayed by the steam that arose from the watery reed.

Wendy Doniger elaborates on this tale further:

He left [the bamboos] and entered a śamī tree; he entered the interior of a śamī, for he wished to sleep . . . the heaven-dwellers yet again went after Agni. A parrot reported that Agni had gone out of the aśvattha and had gone into the interior of a śamī. The gods ran after Agni, who cursed the parrot: "You will be deprived of speech". And the Oblation-eater then turned around the tongue of the parrot, too. But when the gods saw the blazing fire, they were filled with compassion for the parrot, and they said to him, “Bird, you will not be entirely deprived of speech. Though your tongue will be turned around, you will have speech confined to “ka”, sweet, indistinct, and wonderful, like the speech of a child or an old man”. When the gods had said this, they spied Agni in the interior of the śamī, and so they made that tree the sacred abode of fire, for all rituals. From that time forth, Agni is considered to be within the interiors of śamī trees, and men use it as a means of producing fire. And the waters of the subterranean regions, which had been in contact with the deity of bright lustre and heated by the energy of the Purifier when he lay in them, they release their steam through the mountain streams (Doniger:103).

There is a custom of worshipping the khejari tree before heading off to war, and also during shastrapujan at the time of Dussehra. This connects to two instances in the epics. In the Ramayana, Rama is said to have sought the blessings of the shami tree on the eve of the final battle with Ravana. In the Viratparva of the Mahabharata, the Pandavas are compelled to spend the last year of their exile incognito as per the conditions of their 14-year exile. They must each choose a disguise, and hide their true identities and weapons for the duration of the last year. After much thought, and advice from the goddess Durga, they make a bundle of their weapons and hide them in the hollow of a shami tree. To deter any inquisitive passers-by, the bundle is then covered by a corpse. Needless to say, the Pandavas return after a year to find their weapons intact and so offer a prayer of thanks to the shami tree. From this follows the tradition of worshipping the shami tree as a storehouse of fire, weapons and warrior’s luck.

Another legend ascribes the shami as the seat of the goddess Durga, referred to as Shamirama. Again, the connection to weapons and battle comes through, as she is a martial goddess. It is also interesting that the earliest depiction of the shami tree is on an Indus Valley seal from Mohenjodaro with a tiger and a female figure. (Fig 3) (Krishna and Amritalingam 2014:7–9)

Fig 3: Seal with thorn tree, tiger and female figure, Harappan culture. (Photo: Wikimedia)

Among the ruling elite, shami or khejari puja was a pre-war ritual, and even today there is an annual Khejari pujan among the Rajput community at Dussehra. (Fig 4) Among the tribal communities, the Bishnoi tribe is well known for its rigid ‘ecoreligion’ that holds all life forms including trees to be sacred. They take pride in going to extreme lengths to conserve the ecology of their area. In 1778, legend has it that 294 Bishnoi men and 69 women led by Amrita Devi, sacrificed their lives to protect a grove of khejari trees from being chopped by the local potentates men.

Fig 4: Maharaja Gaj Singh performing Khejari pujan at Dussehra at Jodhpur. (Photo courtesy Mehrangarh Museum Trust, Jodhpur)

Wall Painting

Rajput court painting, which reflected the attitudes and predilections of the ruling class, faithfully recorded the allegory and significance of sacred trees. The banyan or ashvattha in Vedic cosmology is the overarching Creator-tree, with upside down roots. It represents the Creator as well as Creation, and is the ideal choice for meditation and prayer. Krishna is revered through the symbolism of the tree, either the kadamba or the amla. The mango tree has always, since ancient times, been a symbol of prosperity and fecundity. Court ateliers illustrated the Bhagvata purana, the Epics and the Nath charitas, where along with depictions of courtly pursuits and interests such as hunting, music and portraiture, one finds saints pondering under banyan trees and lovers sighing into mango blossoms.

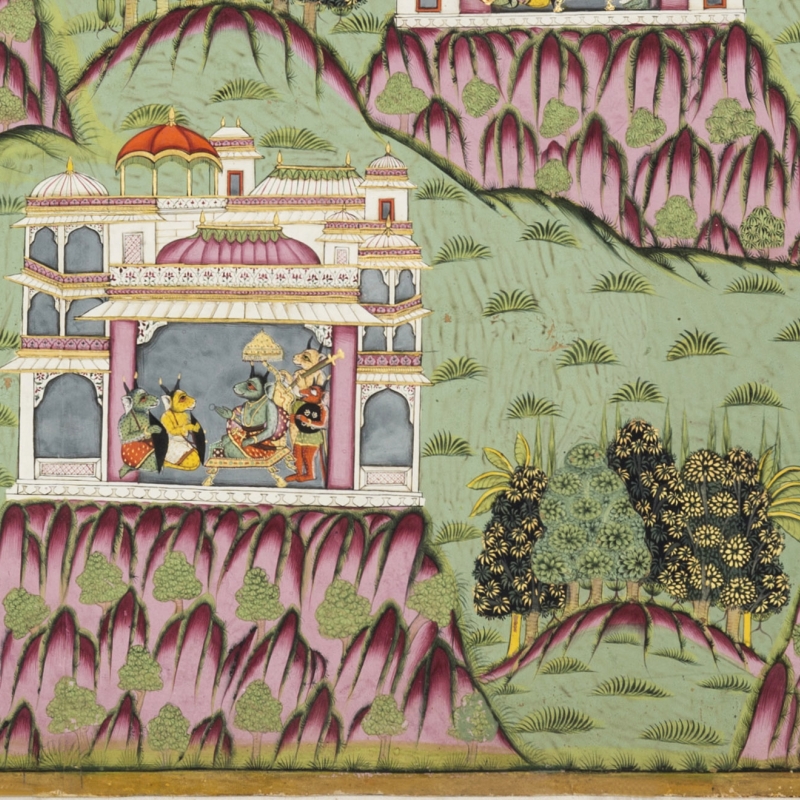

However, what strikes the eye in these paintings is the unique landscape of the Thar, which finds stunning expression through the brushes of the Marwar artists of the 18th century. At the Jodhpur court, they laboured over large-sized, incredibly detailed paintings where one sees a dramatic rocky terrain of deep pink or undulating ochre dunes, all decorated with clumps of bushes and lonely trees, wholly evocative of the landscape of maroosthal, or the ‘land of death,’ which was the traditional appellation for the difficult desert land west of the Aravallis (Tod Vol I,1829:1).

The artists faithfully recorded the starkness of bare rocks, and the vivid colours and the contours of rolling dunes speckled with vegetation. In figs 5 and 6, there are isolated trees perched on rocky outcrops, and solitary clumps of thorny bushes or grasses across the plains, whether grassy or sandy. In fig 7, which is an illustration of an episode from the Bhagvata Purana, the rocky hill occupying centre stage is in sharp contrast to the surrounding flat, sandy, yellow landscape. One can see the same view, albeit less stylized, from any citadel in Jodhpur, Jaisalmer or Bikaner. In fig 6, it is interesting to see small verdant groves set apart from the citadels, as small round patches of green amid a sea of rock and arid desert. It is much the same today, with sacred groves or orans being located outside the town or village limits. (Figs 8 & 9)

Fig 7: Krishna approaches the Citadel of Naraka. Folio from Bhagvata Purana, 1710, Bikaner. (Photo: Wikimedia)

It is noteworthy that the impulse to adorn the walls of a dwelling springs equally in both palace and hut. Royal buildings followed the mural styles of Mughal palaces and tents, with elaborate stylised, polychrome, flowering plant motifs in geometrically aligned niches and wall panels. They sculpted and painted blooms of jasmine, iris, rose and marigold to bring gardens into their living spaces. (Figs 10 &11)

However, in village huts, one sees a free flowing landscape of floral and geometrical motifs rendered in white, ochre and rust shades. The materials used are chuna (or lime), geroo (or red ochre) and mud. This is the traditional mandana or wall and floor painting. Here it is possible to trace stylised thorny branches of the shami or hingot (desert date), dotted berries and round fruit as seen in bordi (indian jujube) trees. The detailed cross hatching infills are strongly reminiscent of the tangled, leafless stalks of the kair bushes. (Figs 12 &13)

Fig 10: Wall decorations at Hadi Rani Mahal in Nagaur Fort. (Photo: Wikimedia)

Fig 11: Floral patterns in wall carving at Mehrangarh Fort, Jodhpur. (Photo: Malini Saigal)

Fig 12: Mandana patterns on mud huts in a village. (Photo: D’source Design Gallery)

Fig 13: Mandana patterns on a mud wall show trees or large bushes with small leaves and round berries, as well as spiky borders or grasses

(Photo: D’source Design Gallery)

Folklore

The emotive power of the landscape and trees comes through most clearly in oral literature. The pan-Indian concepts of tree spirits, of magic wish-fulfilling trees or kalpavrikshas are found aplenty in the bardic tales and folklore of the Thar. One of the popular narratives is that of King Bhartihari of Ujjain and his favourite queen Pingala. When the king sends a messenger with the false news of the king’s death, the queen refuses to believe it.

Queen Pingala had a magic tree. She had planted a magic tree, and if King Bhartihari had a mere splinter, one of its branches would wither.

Now the queen looked at the magic tree, and it was blossoming and blooming as usual.

“O royal servant, King Bhartihari, my husband-god, hasn’t even a splinter, you are lying.” (Gold 1992:116)

In 'Duvidha' (or 'Dilemma'), Vijaydan Detha’s seminal short story based on a popular folk tale, the mischievous spirit at the centre of the tale resides in a khejari tree located near a small pond. As the summer loo blows through the desert, a weary bridal party stops to rest in its shade.

The bride turned aside, lifted her veil and sat down. She looked up—above her hung thin green sangriya beans, more sangriya than she could count. A sheen of cool spread across her eyes just to see the green canopy. Now it just so happened that a ghost lived in that khejari. He caught one whiff of the brides’s perfume, looked at her unveiled face, and was entranced. (Detha 2010:148)

And thereby hangs a tale, brimming with love, longing and tragedy, in true desert style.

Textile patterns

The most culturally significant depiction of plants is to be found in textiles. The Thar region has many distinct social groupings of tribes and castes, itinerant or settled, speaking many dialects and following varied traditions of devotion and ritual. Balotra in the district of Barmer, west of Jodhpur, is well known for its distinctive hand-block printed textiles. These are in shades of indigo, red and yellow, and the combination of pattern and colour makes for an extraordinary visual vocabulary that identifies status, occupation, ethnic and religious affiliation, gender and marital status, and area of habitation. In the case of men, the turbans speak out like a textile Aadhar card, and for the women, who may be heavily veiled, it is the ghagra (skirt) that gives out the information. This kinship on cloth is described as under:

The women, keeping her head covered and face veiled in the presence of men, would have her details stamped on her skirt for easy recognition. A Maali woman from the Balotra region, married with children, would be easily differentiated from a Rabari widow, or a newly married Jat form the same area, avoiding the risk of violating unspoken community taboos . . . The most distinctive of the nomadic groups are the Rabari herders, Banjara traders and gadia Lohar blacksmiths, all immediately recognisable by their characteristic use of dress and body ornament (Anokhi, Balotra: 25).

Subgroups within the main groups all have variations on appearance for easy identification.

Balotra Prints

There are about 19 simplified plant and object motifs drawn from everyday life around the wearers. Some of the plant motifs are as follows:

Phooli: Motifs of intertwining flowers worn by the Mali community, whose occupation is growing flowers and vegetables and making temple garlands.

Gainda: Motifs of marigolds (Tagetes erecta or Tagetes patula) worn by middle-aged Mali women. Marigolds are widely cultivated in the region for their medicinal properties, dyes, and use in ceremonies and worship.

Chameli: Motifs of the scented jasmine plant. Interestingly, only worn by Mali widows.

Babooliya: A motif of the small-leaved desi babool twig (Acacia nilotica). Traditionally worn by widows of any tribe.

Rabari ro fatiya: A sprigged motif similar to the babooliya, but worn only by widows of the Rabari community.

Goonda: A striped design with a bel (or twining line) of berries of the kair bush (Capparis decidua). Married women of the Chaudhary and Jat communities wear this pattern, and, as the berries are a staple food, perhaps this indicates domestic skills.

Boriya: This is a pattern of a thin, checkered stripe interspersed with round fruit of the bordi tree (Zizyphus nummularia). This is worn by women of the Kumhar or potter tribe.

Trifuli: This is a three-flowered motif, worn by young girls before marriage.

Mobariya fatiya: This is a single flower motif, resembling a ripe cotton pod. The widows of the Meghvals—a community of handloom weavers that make the coarse cotton cloth on which these designs are printed, wear them.

Conclusion

The flora of a region, as reflected in its cultural consciousness, is a new area of study. It explores interrelated aspects of the economic, medical, religious and artistic significance of plants, under the general umbrella term of 'ethnobotany'. This essay touches on a few features of the flora of the Thar and its links to local communities, but there are many more aspects yet to be explored.

References

Ajrakh: Patterns and Borders. 2007. Jaipur: Anokhi Museum of Hand Printing

Balotra: The Complex Language of Print. 2007. Jaipur: Anokhi Museum of Hand Printing

Detha, Vijaydan. 2010. Choubuli and other stories, vols I & II. Christi A Merril and Kailash Kabir (trans.). Delhi: Katha

Doniger, Wendy. 2004. Hindu Myths: A Sourcebook translated from Sanskrit. London: Penguin Classics.

Krishna, Nandita and M. Amrithalingam. 2014. Sacred Plants of India. New Delhi: Penguin.

Gold, Ann Grodzins (trans.). 1992. A Carnival of Parting: The Tales of King Bharthari and King Gopi Chand as sung and told by Madhu Natisar Nath of Ghatiyali, Rajasthan. Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

Tod, James. 1829. Annals and Antiquities of Rajast’han or, the Central and Western Rajpoot States of India, vols I & II. Douglas Sladen (ed.) 1997. New Delhi: Rupa and Co.