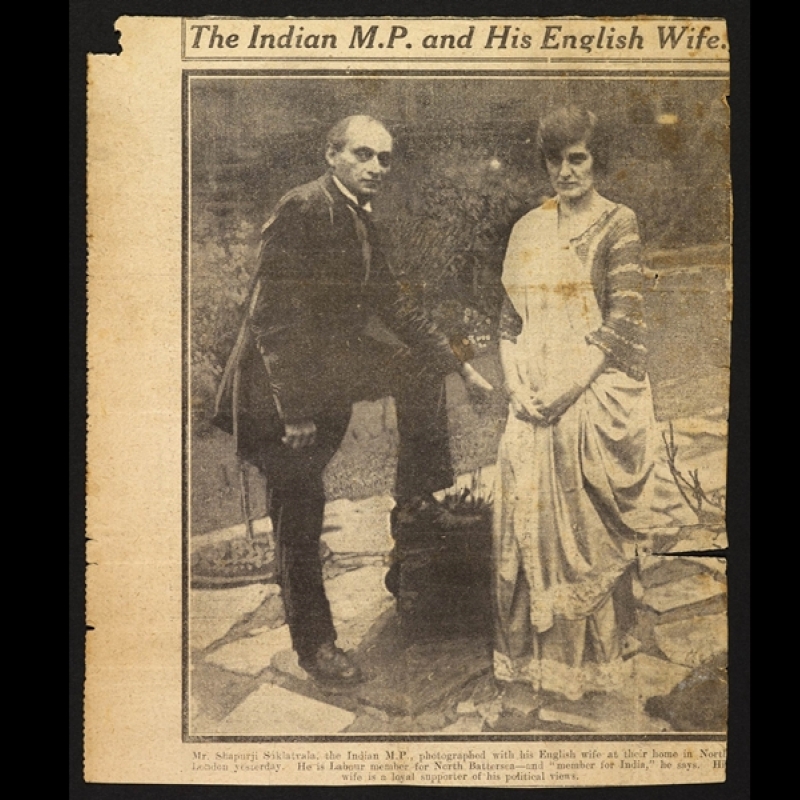

India voted for the first time after independence in 1951, however, the elective element for Indian natives in legislative bodies dates back to 1909. This excerpt from V.S. Rama Devi and S.K. Mendiratta's book 'How India Votes: Election Laws, Practice and Procedure' sheds light on the history of voting and elections in India during the British rule. (In lead photo: Shapurji Saklatvala, the third Asian politician to be elected to British parliament, with his English wife Sarah Elizabeth Marsh. He was was elected MP for Battersea in 1922. He also campaigned for Indian independence; Photo Source: Creative Commons via British Library)

This is the second article in a two-part series. The first part, History of Elections in India, can be read here.

Elections in the modern form, where electors registered on the electoral rolls of well-demarcated territorial constituencies express their choice, by means of ballot papers and ballot boxes, in favour of those whom they wish to represent them in the decision-making institutions, like the Parliament, have seen their evolution in India in the early part of the twentieth century. Even in the nineteenth century, the British Parliament, when it took over from the East India Company, under the Government of India Act 1858, the governance of Indian territories under its occupation after the first war of independence which broke out in India for freedom from the British in 1857, had provided for the constitution of bodies to legislate on local laws under the Indian Councils Acts of 1861 and 1892. But the legislative bodies created thereunder were small bodies, consisting only of nominated members, with no representation of the local people under the former Act and with a small element of local representation under the latter. The elective element for the natives in legislative bodies in British India found its introduction for the first time under the Indian Councils Act 1901. This Act was passed by the British Parliament to give approval to a scheme, known as the Morley–Minto Reforms, drawn by Lord Minto, the then Governor-General of India, and Lord Morley, the then Secretary of State for India in the British Cabinet, in 1906. The Act provided for the setting up of legislative councils at the Centre under the governors. The first Central Legislative Council constituted under the Act consisted of 68 members, of who 27 were elected members[i]. They were, however, chosen not by the common people of India but by special constituencies, such as municipalities, district and local boards, universities, chambers of commerce and trade associations and groups of persons such as landholders or tea-planters. Further, this Act, far from being beneficial to the Indian people, was responsible for sowing the seeds of communal disharmony and hatred between Hindus and Muslims, which ultimately led to the partition of India in 1947 into two separate countries, India and Pakistan, on the ground of religion. The said Act provided that certain seats in the legislative councils would be reserved exclusively for Muslims and the members to hold those seats who be elected by separate electorates consisting of Muslim electors only.

Also Read | How India Votes: History of Elections in Ancient India

The legislative bodies created under the Indian Councils Act 1909 continued up to 1915, when the Government of India Act 1915, superseded the earlier Act. This Act of 1915 was further amended by the Government of India Act 1919 (the 1919 Act) to bring in the reforms, known as Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms, suggested by Mr Edwin Montagu, the then Secretary of State for India, and Lord Chelmsford, the then Governor-General. The 1919 Act was considered to be some improvement over the earlier set-up under the 1909 Act. However, it also continued the old practice of reservation of seats for Muslims and separate electorates for them. In addition, for the first time, this Act provided for further reservation for Sikhs. Under this Act, a bicameral legislative body was created at the Centre—the council of State as the upper House, and the Central Legislative Assembly as the lower House (s 63, 1919 Act)[ii]. For the first time, the elected members constituted the majority in each of the Houses. The Central Legislative Assembly was to consist of 145 members, of which 105 were to be elected under the remaining to be nominated (s 63B ibid[iii] and the rule made thereunder). The tenure of the Assembly was to be three years (s 63D ibid)[iv]. The Council of State was to have 60 members, of which 34 were to be elected, and the rest would be the Governor-General’s nominees (s 63A ibid[v] and the rule made thereunder). The term of the Council was to be for five years (s 63D ibid)[vi]. Though the Act provided for direct elections from the constituencies to both the Houses, only a limited number of persons were granted the right to vote on the basis of certain high qualifications, like, the ownership of property, or payment of income tax, or payment of municipal tax, or the holding of land, etc (r VIII r/w Sch II of the Legislative Assembly/Council of State Electoral Rules under ss 23 and 64 of the 1919 Act)[vii]. The franchise to the Council was far more restricted. Property qualifications had been pitched so high as to secure the representation of only the wealthy landowners and merchants. For other interests for whom seats were reserved, previous experienced in a Central or provincial legislature, service in the chair of a municipal council, membership of a university senate and similar tests of personal standing and experience in public affairs were necessary qualifications for a vote. [viii]

The elective element for the natives in legislative bodies in British India found its introduction for the first time under the Indian Councils Act, 1909 (Photo Source: Public.Resource.Org/Flickr)

The 1919 Act also fell far short of the demands and expectations of the Indian people. The Indian National Congress spearheading the freedom movement described it as ‘inadequate’, ‘unsatisfactory’ and ‘disappointing’ in its Annual Session of 1919. In May 1928, an all-party conference was held in Bombay, and a committee was appointed under the chairmanship of Shri Motilal Nehru to determine the principles for a Constitution of independent India. The committee, inter alia, proposed the political status of India as being the same as that of other British dominions—Australia, Canada, South Africa—a bicameral Parliament for India, universal adult franchise, joint electorates with reservation of seats for minorities on the basis of population, and so on. As a result of disenchantment of the Indian people with the constitutional set-up under the 1919 Act, the British government held a series of Round Table Conferences with the Indian leaders. It then published a White paper in March 1933, proposing a new constitutional order for India with dyarchy at the Centre, and a responsible government in the provinces. However, the White Paper was also rejected by the people of India. Regardless of this rejection, the British Parliament passed, on 2 August 1935, the Government of India Act 1935 (the 1935 Act). This Act envisaged a federal set-up of the British provinces and the Indian princely states. It proposed to set up a bicameral federal legislature. It was to consist of an upper House, called the Council of State, and a lower House, called the House of Assembly or Federal Assembly [s 18(1) ibid][ix]. The total membership of the Council of State was not to exceed 260, of whom not more than 104 were to be the representatives of the rulers of the Indian princely states. The remaining 156 members were to be the representatives of the British provinces. Of these 156 members, six were to be nominated by the Governor-General, 75 were to be elected by Hindus and others in general constituencies, 49 by Muslims, four by Sikhs, seven by Europeans, two by Indian Christians, one by Anglo-Indians, six by women and six by Scheduled Cases [s 18(2) r/w the First Schedule, ibid][x]. They were to be elected directly from constituencies, but on a very narrow franchise. They were to remain in the Council for nine years, one-third of them retiring after every three years [s 18(4) ibid][xi]. The Council was, thus, to be a permanent chamber. The Federal Assembly was to consist of not more than 375 seats, of which not more than 125 seats were to be filled by representatives of the rulers of the Indian princely states. The remaining 250 seats were to be represented by the British provinces. These seats were to be filled by election by the members of the provincial legislative assemblies [xii] [s 18(2) r/w the First Schedule, ibid][xiii]. Thus, the elections to the Federal Assembly were to be indirect. Here also, the communal electorates were encouraged. For instance, 82 seats were given to Muslims, eight each to the Indian Christians and the Europeans, six to Sikhs and 105 were general seats. The tenure of the Federal Assembly was to be five years [s 18(5) ibid][xiv]. The eligibility for enrolment as electors for the above elections was also restricted and was dependent on taxation, property, education, government service, etc, and varied from state to state (Sixth Schedule to the 1935 Act).

However, the federal scheme as envisaged under the 1935 Act never came into operation and remained a provision only on paper. In fact, the Act itself had foreseen such eventuality and had made transitory provisions for transitional Indian legislature until the establishment of the proposed federation. As per that transitional arrangement, the constitutional set-up under the 1919 Act as described above was continued. The 1935 Act also provided for a legislature in every British province. Assam, Bengal, Bihar, the United Provinces, Bombay and Madras were to have bicameral legislatures, consisting of two chambers, namely, the legislative assemblies and legislative councils; the other provinces were to have a single chamber called the legislative assembly (s 60 ibid)[xv]. The strength of these assemblies and councils varied from province to province [s 61(1) r/w Fifth Schedule, ibid][xvi] Whereas the legislative councils were to be permanent chambers with one-third of their members retiring every third year, the legislative assemblies were to have a term of five years, unless dissolved earlier by the provincial governor [s 61(2) and (3) ibid][xvii].

This is the second article in a two-part series. The first part, India Votes: History of Elections in India, can be read here.

Excerpt reproduced from V.S. Rama Devi and S.K. Mendiratta's book How India Votes: Election Laws, Practice and Procedure (LexisNexis, 2007), with the permission of the publisher.

Notes

[i] Subhash C Kashyap, History of the Parliament of India (New Delhi: Shipra Publications, 2000), 55.

[ii] Section 63 of the 1919 Act.

[iii] Section 63B of the 1919 Act.

[iv] Section 63D of the 1919 Act.

[v] Section 63A of the 1919 Act.

[vi] Section 63D of the 1919 Act.

[vii] Rule VIII read with Schedule II of the Legislative Assembly/Council of State Electoral Rules under sections 23 and 64 of the 1919 Act.

[viii] A. Gwyer and M. Appadorai, Speeches and Documents on the Indian Constitution, vol 1 (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1957), 32–33.

[ix] Section 18 clause (1) of the 1935 Act.

[x] Section 18 clause (2) read with the First Schedule of the 1935 Act.

[xi] Section 18 clause (4) of the 1935 Act.

[xii] B. Shiva Rao, The Framing of India’s Constitution, A Study (New Delhi: Universal Law Publishing Company, 2006), 13.

[xiii] Section 18 clause (2) read with the First Schedule of the 1935 Act.

[xiv] Section 18 clause (5) of the 1935 Act.

[xv] Section 60 of the 1935 Act.

[xvi] Section 61 clause (1) read with Fifth Schedule of the 1935 Act.

[xvii] Section 61 clauses (2) and (3) of the 1935 Act.