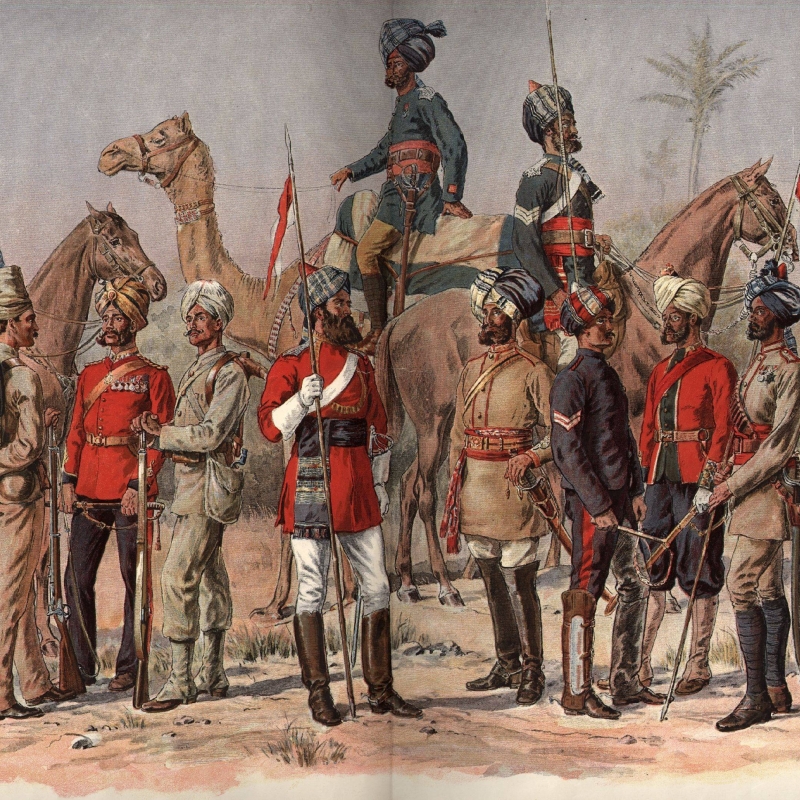

The Vellore Mutiny of 1806 is one of the earliest examples of India’s resistance against the British. Sahapedia takes a look at the revolt and its significance. (In pic: A painting showing sepoys from the Madras Army in the early 1800s; Photo courtesy: Wikimedia Commons)

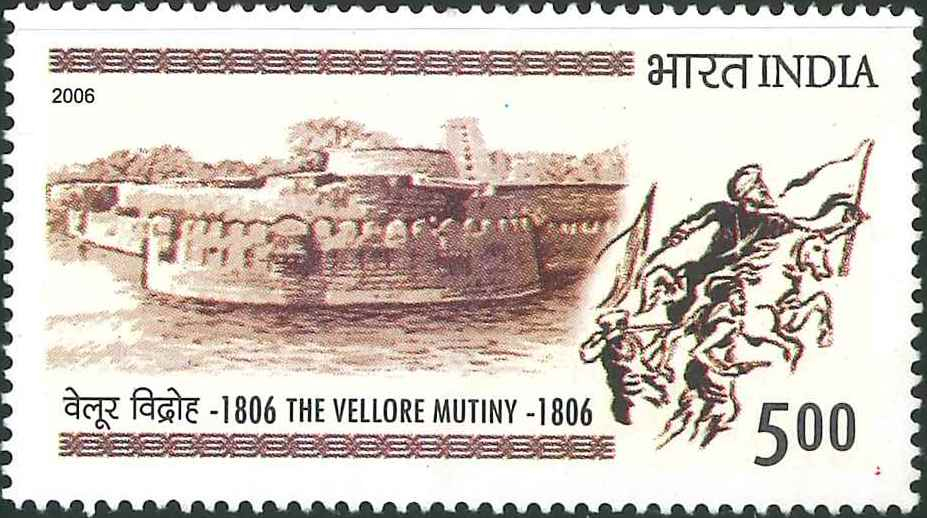

The Mutiny of 1857 was a significant event in Indian history that led to numerous uprisings against the British. While the revolt was called the ‘Indian insurrection’ by the German philosopher Karl Marx—who wrote about it in the New York Daily Tribune—Jawaharlal Nehru and V.D. Savarkar called it the ‘First War of Independence’.[1] Though the 1857 rebellion is often remembered as the first cry against British imperialism, not many know that the Vellore Mutiny of 1806 was, in fact, the earliest instance of the deep-seated resentment against the British—coupled with the political goings-on at the time—leading to a rebellion.

Mysoreans in Exile

In 1799, the British troops, with help from the nizams of Hyderabad, took over the kingdom of Mysore from Tipu Sultan after the Siege of Seringapatam (an anglicised version of Srirangapatnam)—an event that turned the river Kaveri sanguine. After Tipu Sultan was killed on May 4, the British handed Mysore over to the Wodeyars (the former rulers of Mysore). Tipu’s children and their families were exiled to Vellore. However, this strategy soon came back to haunt them.

Also read | Nine Museums for the Patriotic Indian

In Tiger of Mysore: The Life and Death of Tipu Sultan, Denys Forrest notes that Tipu’s children, their families and ‘innumerable servants’ formed a community of ‘Mysoreans in exile which numbered up to 3,000 souls and split over a considerable area around Vellore’. Tipu’s progeny soon began conspiring to avenge the death of their father and leader.[2]

The Insurrection

On November 14, 1805, six years after the bloody battle at Seringapatam, an order was issued by Sir J.F. Craddock, commander-in-chief of the British troops, detailing the new military dress code. According to the order, the sepoys had to dress in a uniform and shave their facial hair, could no longer mark their castes and were forced to wear a leather turban that had a cockade made from cow hide. Though the order was passed to establish uniformity, the ‘upper-caste’ Hindu sepoys objected to wearing leather headgear, stating that this would get them excommunicated from their castes.[3]

When 21 sepoys from the Second Battalion, Fourth Regiment expressed their resentment, they were subjected to corporal punishment and faced public lashing at Fort St. George in Madras (now Chennai). However, scholars such as K.K. Pillay state that similar dress regulations were introduced in ‘Hyderabad, Bellary, Wallajabad, Bangalore and Nundidrug’, and that it was ‘doubtful whether these regulations alone served as the cause of the Vellore Mutiny’. He insisted that the presence of Tipu Sultan’s children in Vellore was ‘the fundamental factor which gave a shape to the rebellion’.[4]

The Crimson Tide

On the morning of July 10, 1806, the sepoys attacked Vellore Fort. A massacre followed, in which more than 100 British soldiers were killed—many of them shot while they slept. The British flag was lowered by the sepoys, and Tipu’s flag—given to them by Tipu’s fourth son Moizuddin—was hoisted. K.K. Pillay, in his paper, ‘The Causes of the Vellore Mutiny’, wrote that it ‘was Mozeeuddin [sic] who orchestrated the attack in order to escape Vellore to go to Madras, where his supporters were awaiting the return of the family.’ When a British cavalry regiment from Arcot reached the fort, it was already in possession of the mutineers. Soon, though, most of them were killed by the British forces and the rebellion was crushed.

John Blakiston—an officer in the relief force commanded by Sir Rollo Gillespie that was charged with regaining possession of the fort—later recounted that the bodies of more than 800 sepoys were carried out of the stronghold ‘besides those who were killed after they escaped through the sally-port’.[5] In Twelve Years’ Military Adventure in Three Quarters of the Globe, he detailed the events of the day, mentioning that ‘upwards of a hundred sepoys, who had sought refuge in the palace, were brought out, and, by Colonel Gillespie’s order, placed under a wall, and fired at with canister-shot from the guns till they were all dispatched’.[6]

Also read | Bhagirath Palace: Begum Samru’s Forgotten Haveli

Though the Vellore Mutiny is often overshadowed by the events of 1857, its effects were felt in Britain. Eventually, the officers deployed at the fort were questioned about their intentions of introducing the changes that resulted in the revolt. As said the famous saying goes, history doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes, and about 50 years later, the British made a similar decision to introduce Enfield P-53 rifles, which came with pre-greased cartridges made of tallow from beef and pork fat, leading to the Revolt of 1857.

While the history books all cover the 1857 rebellion, not many relate the story of the Vellore Mutiny—one of the earliest examples of Indian resistance against British rule. The Vellore Mutiny preceded its 1857 counterpart by half a century, and served as a portent of the things to come.

Did you know?

- Though the Mutiny of 1857 is largely considered the first revolt against British imperialism, one of the earliest examples of Indian resistance against colonialism is found in the Vellore Mutiny of 1806.

- After the Siege of Seringapatam in 1799, British troops killed Tipu Sultan, took over the kingdom of Mysore and exiled his children to Vellore.

- On November 14, 1805, six years after the bloody battle at Seringapatam, an order was issued by Sir J.F. Craddock, commander-in-chief of the British troops, detailing a new dress code: (1) all soldiers were asked to wear a leather turban, (2) they were prohibited from marking their castes and (3) they were asked to shave their facial hair.

- When 21 sepoys from the Second Battalion, Fourth Regiment expressed their resentment, they were subjected to corporal punishment and faced public lashing at Fort St. George in Madras.

- On the morning of July 10, 1806, the sepoys attacked Vellore Fort and a massacre followed.

- John Blakiston—an officer in the relief force that had arrived to regain the possession of the fort—later recounted that the bodies of more than 800 sepoys were carried out of the fort.

- More than a hundred Englishmen were killed in the mutiny and many of them were shot while they were asleep.

- Historians such as K.K. Pillay believe that Tipu Sultan’s third son Moizuddin was behind the mutiny, as Tipu’s flag, given to the sepoys by Moizuddin, was hoisted after they took over the fort.

- After the news of the rebellion spread, a relief force commanded by Sir Rollo Gillespie arrived from Arcot and regained possession of the fort.

This article was also published on The Statesman.

Notes

[1] Karl Marx, ‘The Indian Insurrection,’ New York Daily Tribune, New York, August 29, 1857. Also see, Inder Malhotra, ‘The First War of Independence,’ The Asian Age, n.d., accessed September 5, 2019, https://web.archive.org/web/20090816180943/http://www.asianage.com/presentation/columnisthome/inder-malhotra/the-first-war-of-independence.aspx.

[2] Siddharth Raja, ‘Tipu Sultan: The Forgotten Connection With India’s First Sepoy Mutiny,’ The Wire, November 10, 2018, accessed September 5, 2019, https://thewire.in/history/tipu-sultan-forgotten-connection-indias-first-sepoy-mutiny.

[3] P. Chinnian, ‘Highlighting Events of the Vellore Mutiny 1806,’ Indian History Congress 45 (1984): 562, accessed September 5, 2019, https://www.jstor.org/stable/44140244.

[4] K.K. Pillay, ‘The Causes of the Vellore Mutiny,’ Indian History Congress 20 (1957): 306, accessed September 5, 2019, https://www.jstor.org/stable/44304481.

[5] John Blakiston, Twelve Years’ Military Adventure in Three Quarters of the Globe (London: Henry Colburn, 1829), 292.

[6] Ibid., 295.