Gyan chaupar (the game of knowledge) is an ancient board game of the Indian subcontinent. It has multiple stories surrounding its origin and has several variants including moksha-pata (board of enlightenment), parampada sopanam (steps to the highest place) and gyanbaz[1] played across the region. These games while similar to gyan chaupar in principles use certain variations of playing style and board design.

While it is difficult to ascertain when the game first appeared, it is generally thought to be around the thirteenth century.[2] Gyan chaupar developed among the Jain saints of western India and was intended to serve moral lessons to the masses.[3] Its purpose was to teach the karmic theory to the younger adherents of Jainism.

The movement of players across the board showed the movement of the jiva (soul) across the various lokas (worlds) before finally attaining siddha (enlightenment) atop the game. The Jain doctrine of the ‘scale of perfection’ was at the heart of gyan chaupar’s design—a player would start from the point of complete delusion and work towards the state of omniscience.[4]

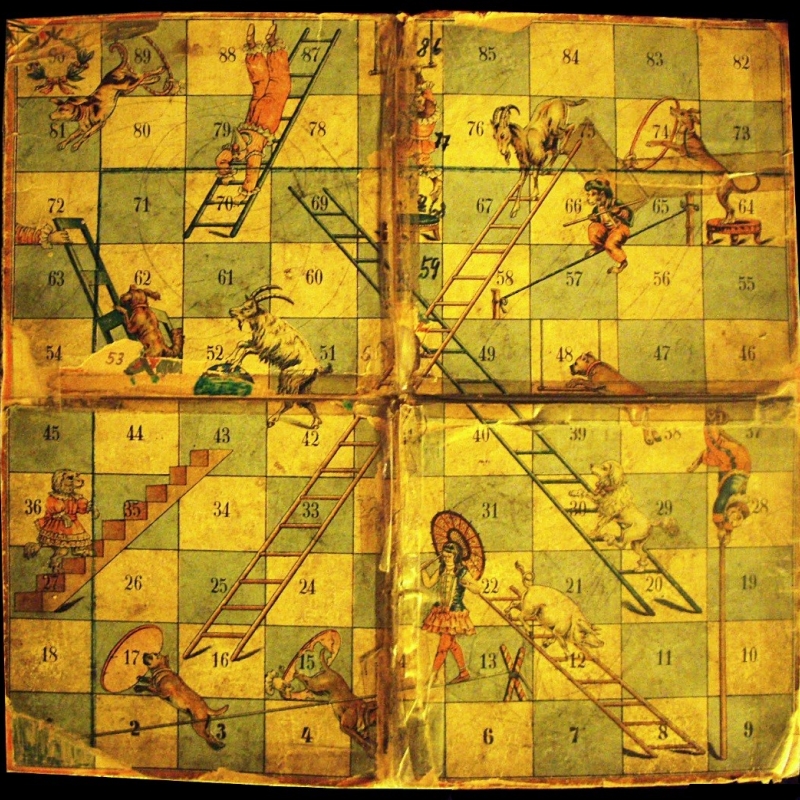

The gyan chaupar board housed at the Decorative Arts Gallery of the National Museum in New Delhi is an example of the Jain version of the game. (Fig.1) It seems to follow the basic rules of the religious philosophy. Though unlike the nine snakes and five ladders seen in most Jain gyan chaupar boards, it has a distinctly coloured extra snake at the topmost box. It is a late-eighteenth century board painted on cloth in the usual 84-box style (9 x 9 plus three additional boxes at 1, 46, 66). The snake at the highest box on the left (76) is the mohani-karma—confusion and desire trying to catch hold of the jiva before it attains enlightenment.[5] This board follows the conventions of the Rajasthani school of painting, evident from the line work on the divine figures at the top, Devanagari inscriptions, floral creeper patterns and red–black colour contrast.

Popularity across Traditions

The Hindu gyan chaupar boards are more complicated than their Jain counterparts. Not only can they have more elements (snakes, ladders and boxes), they also differ in their approach to the game.

One of the reasons for this complexity is that the Hindu gyan chaupar catered to various schools of thought, including Tantric, Samkhya, Yoga and Vedanta. Even the spiritual movements like Bhakti, especially its Vaishnava strand, used the game to convey its ideas to its followers.

Gyan chaupar was adaptable as easily to Hinduism as it was to Sufism, where the upward movement on the board led to Allah rather than Shiva or Vishnu. The wide applicability of the game points not only to its immense popularity in the subcontinent but also its flexible nature. It could transcend philosophical boundaries due to its ability to make apparent abstruse concepts of religious thought. The game was played by kings and commoners, children and adults, and Europeans and Indians alike.

Gyan Chaupar reaches Europe

Snakes and ladders is commonly seen as a Western game. The fact that it is a form of gyan chaupar is often ignored. Few are aware that the game was exported to the West during the colonial rule and reintroduced to the subcontinent.[6]

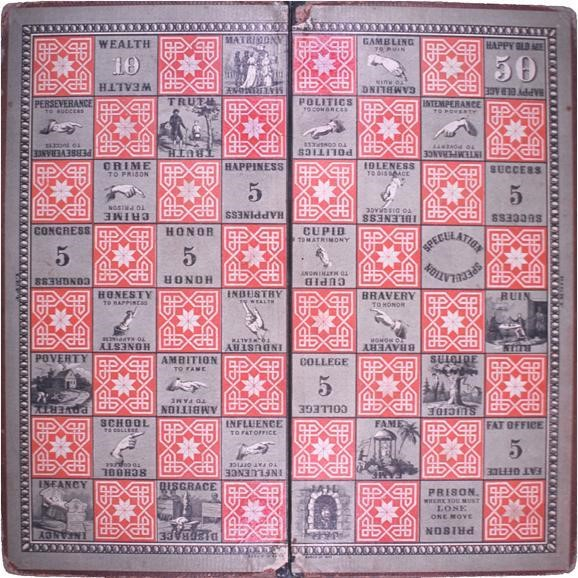

In 1860, American–British entrepreneur Milton Bradley first started selling the ‘Checkered Game of Life’ which was largely based on gyan chaupar. (Fig. 2) It was an instant hit in the West, making it a popular parlour game in the United States, and Bradley an overnight success. The eponymous brand would go on to rule the board games’ market in Europe and North America for years.

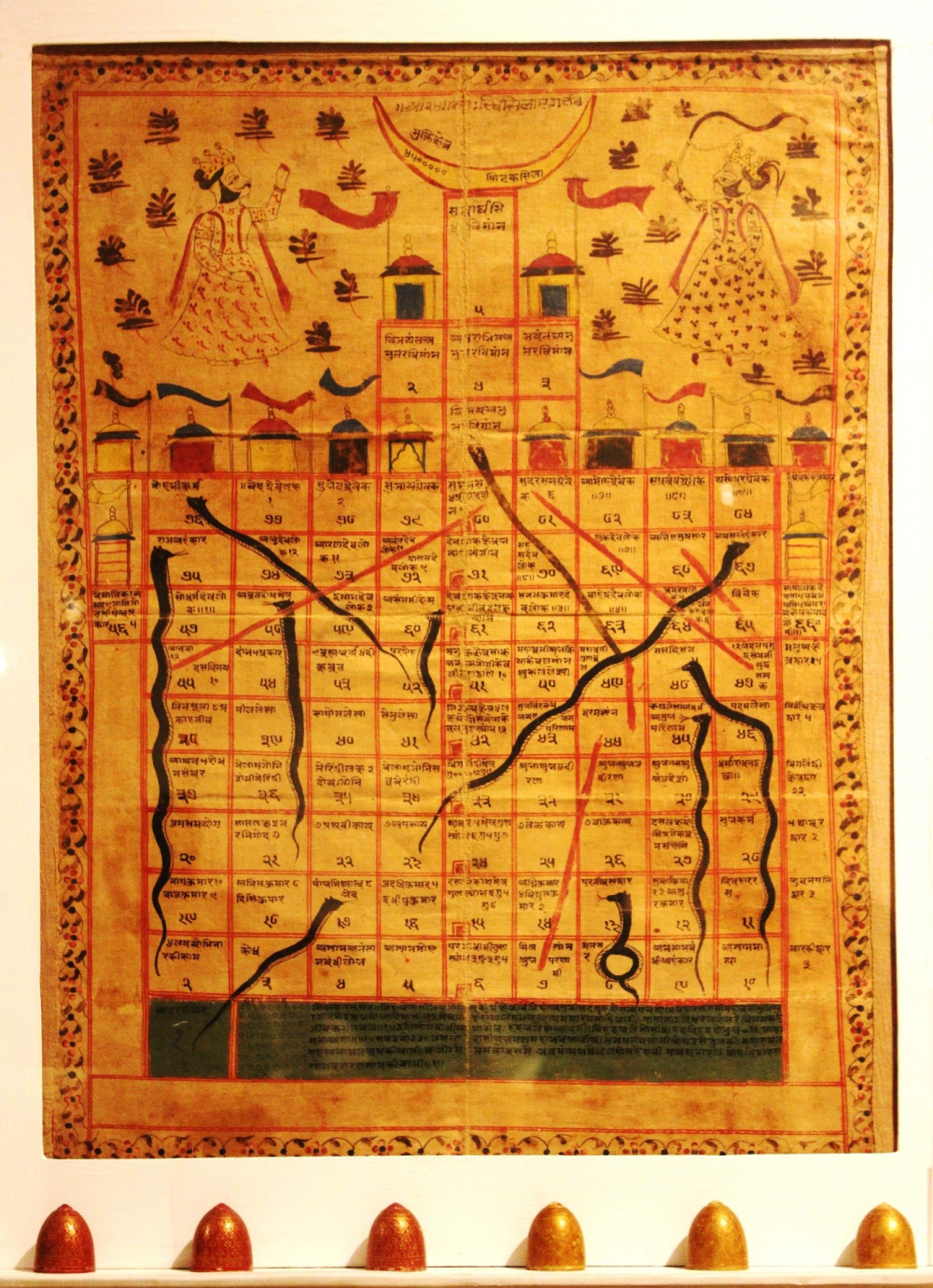

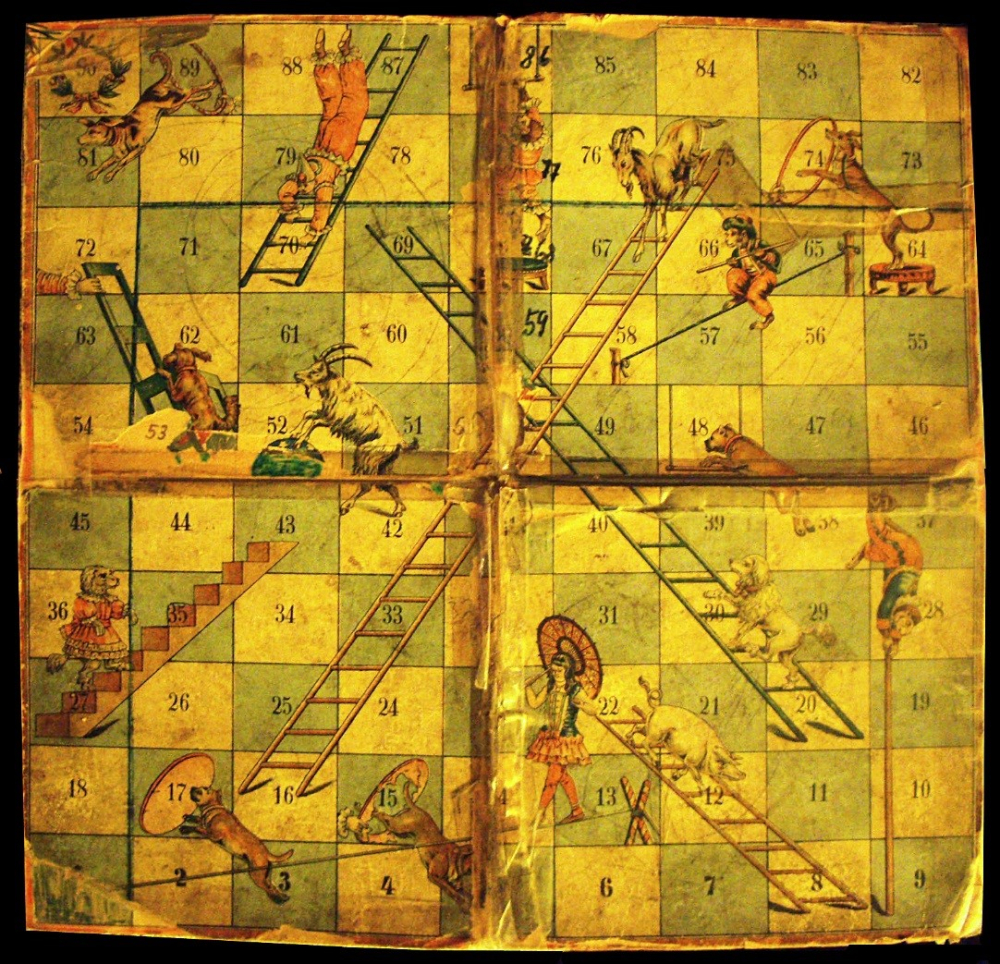

Gyan chaupar also paved the way for the Kismet (fate) game in Europe in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Another version of the game widely played in Germany in the twentieth century was Leiterspiel, literally meaning snakes and ladders. It was developed by J.W. Spear & Söhne and contained circus animals instead of snakes. (Fig. 3) Versions of gyan chaupar with variations like these continue to be played across Europe.

When the British co-opted gyan chaupar, it was translated to suit the Victorian ideals. If the Jain gyan chaupar worked on karmic principles, the Victorian snakes and ladders sought to inculcate Western morals. Ideals such as honesty, grace and patience were rewarded while anger and dishonesty were punished resulting in downfall. Eventually, however, the pressures of the World War II economy made way for the contemporary plainer game based on chance.[7]

Today, even as people move towards virtual-reality gaming environments, gyan chaupar has its niche audience. Its players might prefer android applications of snakes and ladders over physical boards but the game lives on.

Notes

[1]Gyanbazi also means game of knowledge.

[2]Finkel and Mackenzie, Asian Games: Art of Contest.

[3]Topsfield, ‘The Indian Game of Snakes and Ladders.’

[4]Petit, ‘Scales of Perfection.’

[5]Pathak, ‘Gyan Chaupar: A Simple Way of Teaching.'

[6]Chanda-Vaz, ‘Indians are Reviving an Ancient Version of Snakes and Ladders, in which Winning isn’t the Point.’

[7]Topsfield, ‘Dice, Chaupar and Chess: Indian Games in History, Myth, Poetry.’

Bibliography

Chanda-Vaz, Urmi. ‘Indians are Reviving an Ancient Version of Snakes and Ladders, in which Winning isn’t the Point.’ Scroll.in. 2017. Accessed August 7, 2019. https://scroll.in/magazine/837691/indians-are-reviving-an-ancient-version-of-snakes-and-ladders-in-which-winning-isnt-the-point.

Finkel, Irving L. and Colin Mackenzie. Asian Games: Art of Contest. New York: Asia Society, 2004.

Pathak, Anamika. ‘Gyan Chaupar: A Simple Way of Teaching.’ Kala—The Journal of Indian Art History Congress XVI (2010–11).

Petit, Jérôme. ‘Scales of Perfection.’ Jainpedia. Accessed August 7, 2019. http://www.jainpedia.org/themes/principles/jain-beliefs/karma/scales-of-perfection.html.

Topsfield, Andrew. ‘The Indian Game of Snakes and Ladders.’ Artibus Asiae 46, no. 3 (1985): 203–26.

———. ‘Snakes and Ladders in India: Some Further Discoveries.’ Artibus Asiae 66, no. 1 (2006): 143–79.

———. ‘Dice, Chaupar and Chess: Indian Games in History, Myth, Poetry.’ In The Art of Play: Board and Card Games of India, edited by Andrew Topsfield, 11–31. Mumbai: Marg Publishers, 2006.