R. Gyaneshwara Singh is a board game enthusiast and revivalist based in Mysuru. He, along with his colleagues, Raghu Dharmendra and C.R. Dileep Gowda, has visited various parts of India, cataloging and curating traditional board games.Their art organisation Ramsons Kala Prathishthana holds an annual exhibition called Kreeda Kaushalya, now in its 12th year, where board games are displayed to the wider public.

Following is an edited transcript of the interview conducted over phone on February 19, 2019.

Mohit Srivastava: What drew you to the project of reviving ancient Indian board games? What were your inspirations behind the endeavour?

R. Gyaneshwara Singh: I started this project on my own by visiting various towns and villages in 1997; the other team members joined me in 2000. I was curious to know how people in the old days spent their idle time. Today we have social media, before that there was radio and TV, and even before that there were activities like embroidery and knitting. I wanted to go as far back as possible to know what people, especially ordinary folks, did in their pursuit for leisure. This is what drew me to the project. People played board games for leisure but also at times because they were passed on to them as traditions.

M.S.: Tell us some of your observations from all the extensive field trips you undertook to discover traditions of board games?

R.G.S.: We followed a very hands-on approach. We would just spend time with people and play these games with them, learning from them the rules of the games. We found out a lot of interesting things. In South India and western India, a lot of rickshaw pullers and autowallas continue to play these traditional games, often just to pass their time. In South Indian villages, often men, especially the older men, could be seen playing these games under the trees. Women would play the same games in the temple premises or community halls, not publicly. Gambling was quite common too, and would often involve code words as the practice is legally restricted in India.

Games are often found carved in temple premises, etched on their walls, ceilings, terraces of gopurams and floors. For instance, we found a temple in Belur which had the game of aadupuliatta[1] etched on its stone well for people to play. Several major games had their regional variations. Like the game of mancala[2] is played across India, in Himachal Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan and southern India (as ali guli mane or pallanguli).

M.S.: Could you tell us a bit about the process of reconstructing some of these board games that Ransoms Kala Pratishthan has undertaken?

R.G.S.: We have been manufacturing and selling traditional crafts of India (particularly from Mysuru) since the 1970s. For reconstructing board games, we identified some 15 to 20 craft clusters in different parts of the country and studied their forms thoroughly: what colour schemes they used, what raw materials they employed, what broad themes they worked with. And based on this, we reverse integrated the whole process using computers. Our approach is to not just rebuild ancient board games but also to merge them with various local craft traditions. We wanted to do more than just popularise ancient board games; we wanted to revive local craft traditions as well. There can be various ways of manufacturing board games; one can use modern printing and plastic pawning methods, but we wanted to employ local board-game-making traditions.

For example, we built kalamkari board games with the help of artists from Srikalahasti (Andhra Pradesh). We worked with the inlay and woodcarving craft cluster from Mysuru (which is one of the biggest craft cluster in the world employing around 2,000 artisans), Saharanpur (in shisham wood cottage industry), Bangalore (brass work industry) and Jaipur (where we made beautiful marble chaukis with 22-carat gold foil paintings on them). We also worked with artists from Raghurajpur (Orissa) to create board games using palm leaf etching; artists from Channapatana (Karnataka) with turned lacquerware; artists from Etikoppaka (Andra Pradesh), a village famous for its toy industry; and from Solapur (Maharashtra), the hub of power looms in the region, which specialises in pit loom weaving. We also worked with artists in Kinnal (Karnataka), reviving intricate wooden game boards from the time of the Vijayanagara Empire.

M.S.: Your organisation hosts Kreeda Kaushalya, the widely anticipated expo on traditional board games every year in Mysuru. What has been your approach in trying to communicate with younger people and popularise ancient Indian craft traditions among them? And what has been the response to the exhibition?

R.G.S.: We started the exhibition in 2007. In the initial years, our exhibition would continue for a week, now it goes on for about 15–20 days. Mysuru is a small city, but it attracts a great number of tourists. Our exhibition is well attended, and has been growing every year. One has to understand that because we have to actually explain to people how these board games are not just games but works of art, we cannot have that kind of instant mass appeal. As these games are handmade and cannot be produced on a mass scale, their prices are a bit prohibitive. But a lot of people come out of curiosity, essentially first-timers. People are often surprised to learn that there are board games beyond snakes and ladders and ludo.

We also organise game parlours around the time of the expo, where we teach young kids how to play these traditional games. On many occasions, we have gone to the famous Hindu spiritual centre Suttur Mutt on the outskirts of Mysuru, to teach and display ancient Indian board games during their annual exhibition.

M.S.: Another connection of the city of Mysuru to board games is the great nineteenth-century king Krisnaraja Wadiyar III, who ruled over the city for some seven decades. He was a patron of arts and an avid board games designer and enthusiast. How do you view his legacy in the board games of the city in particular and the arts in general?

R.G.S.: Krishnaraja Wadiyar III, or Mummadi as he is often known, was the 22nd ruler of Mysuru. He was placed on the throne by the British when he was all of five years old, after the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War and death of Tipu Sultan in 1799. Although, officially he ruled till 1868, the fact is that from 1831 on, the commissioners appointed by the British looked after the administration. Because all his administrative responsibilities were taken away when he was just 36, Wadiyar turned to art. He revived the Mysore school of painting, built several temples, single-handedly restored the jewellery tradition of Mysore, and employed some of the most eminent musicians at that time in Mysore court. Wadiyar was a board games enthusiast, and during this time he improved several games and even invented a few.

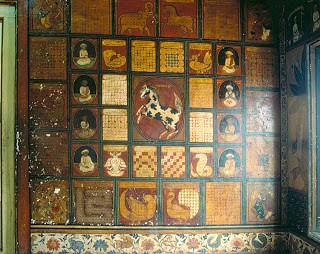

He is said to have been obsessed with the horse movement on the 144-square-chequered chess board. In the early 1800s, he was one of the very few people with the ability to crack the horse movement on the chess board; after all, there is no visual clue to how a horse moves on the chessboard, one has to move the horse without repeating the square. (Fig.1) He introduced variations of pachisi[3]. While the game is traditionally played by four people, he invented versions which could be played by six, eight and even 16 people. He also introduced the morality aspect of the gyan chaupar game to pachisi. These board games can be found at Jaganmohan Palace, painted over its magnificent walls. Some of the most beautiful versions of these are found at British Museum; these were gifted (among other things) by the king of Mysore to the British crown every year when British parliament convened, as the monarch urged them to restore full powers to him.

M.S.: Apart from reviving traditional board games, you have also been involved in a project to revive the ancient doll display tradition of Karnataka which was nearly lost. Your organisation holds an annual exhibition (Bombe Mane) on traditional dolls of the Mysuru style. Could you tell us something about that project?

R.G.S.: Soon after we gained independence in 1947 and Bangalore was made the capital of the state, the focus started to shift from Mysore to Bangalore. Many craftsmen and artisans moved out of Mysore. As Mysore remained a tourist destination, only few artists who created what the tourists were interested in stayed there. The once-famous clay dolls of Mysore eventually disappeared as they were too heavy to be carried by tourists, so even the artists, depending on tourist revenues, started to shift to other professions. The beautiful tradition of clay doll making was all but lost as most potters lost the necessary skills. When we started our research, we could only find specimens of the Mysore style dolls that were made 60–70 years back but nothing recent. We researched the style thoroughly: studied the themes, colours and subjects of these specimens. And we took these designs to artists from Kadanlur, Pondicherry and Madurai, which continued to be thriving centres of Tamil Nadu doll-making industry. This way, the Mysore style doll was revived and now there is some popular interest in them. We have been holding an annual exhibition, Bombe Mane, to promote this craft tradition since 2005.

M.S.: Your father, Sri D. Ram Singh, was a pioneer in manufacturing traditional handicrafts from Mysore for five decades. Now, with your work at Ramsons Kala Pratishthana, do you think the space for manufacturing and retailing traditional Indian handicrafts has changed over all these years?

R.G.S.: One difference is that a lot of things that were produced before are not made anymore. For instance, a lot of work with ivory and horn would take place in Mysore, which have now been banned by the government. Some of the raw materials have gone out of reach of the handicraft industry. Sandalwood, for example, has become extremely expensive due its demand in the beauty industry that provides a return of 300 per cent, something traditional craft can never think of.

Further, some kinds of craft making have just become unviable over the years. The famous Chanapattana tiles have been successfully copied by Chinese producers, and their finish and pricing are more attractive than Indian producers.

Then there are cumbersome government regulations that stand in the way. The stone and metal craftwork industry of Mysore cannot produce anything now because making and parceling their products over to the buyers require procurement of a Non-Antiquities Certificate from the Archaeological Survey of India, which is a long and arduous process.

M.S.: What role do you think the government can play in popularising these traditional Indian crafts?

R.G.S.: Why should we ask the government to do anything—they have their hands full. We should do whatever little we can in our own way. Plus, most of these issues are really local and require specialised knowledge. I am not sure how the government can help here. Our inspiration in the work we do is Kamala Devi Chattopadhyay, who single-handedly revived crafts from across the country and went on to establish the Crafts Council of India. The issue is that most revival projects cannot be executed on a large scale, they have to begin locally, taking local artists along. We do not need to intrude into these local traditions; we have to popularise them without adopting a patronising attitude.

Notes

[1] Aadupuliaatam literally translates to 'goats-tigers game' in Tamil. This is a two-player (or two teams) turn-based strategic board game played in South India. The tigers hunt the goats, and the goats attempt to block the movement of the tigers.

[2] Mancala is one of the oldest extant board games in South India. It refers more broadly to a class of games, involving two-player turn-based strategic moves, with the objective to capture all or some of the opponent’s pieces.

[3] One of the oldest games from the Indian subcontinent, it is played between two to four players on a symmetrical cross using cowrie shells or other forms of die. Players move along the board depending on their throws. Ludo is a modern Westernised version of pachisi.