The history of art schools in India can be traced back to the British era, as many of these schools were established by the British almost 170 years ago. In the second half of the 19th century, the British administration established art schools in the presidency capitals of Madras, Calcutta, and Bombay (Neville 2006). In the beginning, these art schools taught only crafts; other subjects like drawing, painting, and sculpture were added later, followed by teacher training and commercial art courses. In time, a number of art schools and colleges were established, but they limited themselves to training students only in a few subjects, such as painting, sculpture, and applied or commercial art; optional courses included one or two years of printmaking and art history (Mago 1991).

Sir Charles Mallet established the first Western art school in Pune in c. 1790 (Sadwelkar n.d.). This school aimed to train local painters in European painting styles so that they could assist British artists (Mitter 2007). Then, the Calcutta School of Fine Arts was established in 1834. According to B.C. Sanyal, the famous Indian modernist artist, these art schools were established in India to train young local artists in arts and crafts because the British administration needed decorators, draughtsman, lithographers, photographers, sign-writers, and many other types of skilled artisans. The British Government established art schools and invited the children of artisans to train, not only in crafts, but also in their hereditary professions, such as carpentry, smithing, wood turning and lacquer finishing, enameling and so on. However, they learned these skills through the lens of Western academic training, as they were taught to imitate and study Greco-Roman plaster casts and mid-Victorian styles of English painting (Sanyal 1980).

In order to promote industrial art in North India, a colonial school was established in Lahore in 1875—the Mayo School of Art; John Lockwood Kipling was its first principal, from 1875 to 1893. This school was dedicated to the late Lord Mayo, the Viceroy of India from 1869 to 1872. The main purpose of this school was to train local artisans in drawing, design and painting (Srivastava 1983), and also to encourage artisans to engage in all kinds of decorative and applied arts (Bhattacharya 1994).

Gradually, this school became a major art institution in northern undivided India, and it had a great impact on the art scene in Punjab. During the Partition of India, Lahore—the nucleus of artistic and cultural activities in Punjab and the founding place of the Mayo School—became a part of Pakistan, and Shimla became the new cultural capital of Punjab. To encourage artistic activities in the region again, a new art school—the Government School of Art and Craft—was founded in Shimla, with the approval of the then Governor of Punjab. This school operated with the same ideology as the Mayo School.

In the founding of the school in Shimla, S.L. Parasher, former vice principal of the Mayo School of Art, played a seminal role. Parasher had previously sent a proposal to S.N. Kapoor (the then Director of Industries in East Punjab) to establish a government school of art and design in Shimla on July 26, 1948. Initially, the art school was meant to be established in Jalandhar, but as the Government Woodworking Institute was already based there, it made no sense to have two institutes in the same district. The Governor of Punjab gave administrative approval on 5 April 1951 (letter no. 952-I & C -51/1133), and the school was set up under the ambit of the Department of Industries. In the words of Mago (2001, 82), ‘The school conducted five-year diploma courses in Painting, Sculpture, and Commercial Art, besides five-year diploma courses in five arts and crafts: ironsmithy, metal-craft, wood-craft, lacquer-turning and enamel jewellery.' Besides this the school also introduced the study of the culture of the country.

This school was situated next to the Rashtrapati Niwas building (now known as the Indian Institute of Advanced Study). S.L. Parasher was made responsible for preparing the syllabus of the new school. Later, Parsher became the founding principal of the school in Shimla. Apart from being an imitation of the Mayo School, the school in Shimla aimed at establishing and maintaining a tradition of good craftsmanship, propagating the study of design and imparting education to local artists. In addition, the school also provided employment to the many staff members from the Mayo School of Art, Lahore, who had moved to India after Partition, and were unemployed.

Parasher encouraged a number of artisans to join the school and develop the art scene, not only at the school, but also at the then capital of Punjab. Parasher appointed a number of illustrious artists who served in different capacities as instructors and mentors at the school. P.N. Mago and N.K. Dey were appointed as senior teachers in the school. He appointed Baldev Raj Rattan, Maghar Singh, Master Pritam Singh (head of carpentry), A.C. Gautam (head of art), R.R. Trivedi (head of clay modelling) and Amar Singh (head of repousse and jewellery) as senior instructors. Besides this, Piara Singh, Kanwal Nain Kwatra, Vishwa Raj Mehra, Hazara Singh, Sujan Singh and Satish Gujral also joined the school at Shimla as faculty members. Sujan Singh’s father, Sunder Singh, a former faculty member at the Mayo School, Ved Prakash Ghai, Bali Ram, Jit Singh, and R.M. Chatterjee were appointed as junior heads. The staff members had been trained at different art institutions in the country, like the Calcutta School of Art, Calcutta, Mayo School of Art, Lahore, Visva-Bharti University, Santiniketan, Sir J.J. School of Art, Mumbai, and College of Art, New Delhi.

In the beginning, most students came from rural backgrounds and were not adequately trained or educated to take a written admissions test. To bypass this, the staff held interviews with prospective students. The syllabus was divided according to the three main departments—Kala Bhaag (Art Department), Yantra Bhaag (Design Department), and Vaastu Bhaag (Architecture Department). There was a compulsory preparatory course for each of the departments. The course included a general design section, architecture section, and subjects such as drawing and painting, commercial art, light metal work, iron work, wood work, clay modelling, and lacquer work. Students had to pass the compulsory sections in the preparatory course, following which they opted for other subjects. After completing five years of study, they were awarded diplomas.

The specialisation subjects offered by the Design Department included free-hand drawing, design, geometrical drawing, clay modelling, art history and imaginative drawing. These subjects were meant to train fresh students, most of whom did not come from artistic backgrounds or have any training in art. Each topic was divided into various parts; for instance, in geometrical drawing, students would study geometrical shapes as well as ratio and proportion. The syllabus was not just skill-oriented. In addition to Western art history, students were also introduced to Indian art history, mainly Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro.

All the departments modified the syllabi according to students’ progress. Craft courses in textiles, inlay, and ivory were also introduced, but these were optional. After completing the preparatory course, students could take up a one-year postgraduate course. This course included handicraft design, theatrical and stage design and interior decoration, and students were free to choose the subject of their preference.

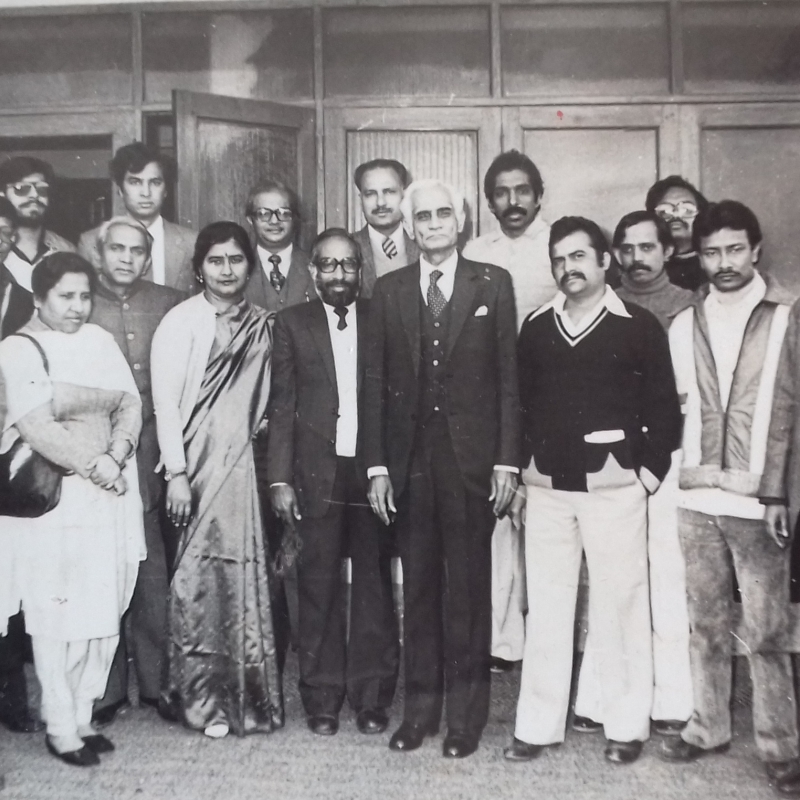

In a short period of time, the school made a great impact on the art scene of Shimla. In order to encourage artistic activities and budding young artists, the staff made students go outside to paint and sketch. Gradually the ridge, the mall and other picturesque views of the valley became favourite spots for students to paint (personal communication with S.L. Diwan, January 2018). Under Parasher’s principalship the Shimla School of Art and Craft produced a number of luminous artists—S.L. Diwan, Jawahar Diwan, Sohan Qadri, Shiv Singh, R.S. Rania, Gulzar Singh Gill, to name a few.

In 1959, Parasher retired and shifted to New Delhi. Sushil Sarkar, a graduate of the Bengal School of Art, joined as the new principal. During Sarkar’s principalship, the school suffered from a lack of funding. However, this did not diminish Sarkar’s efforts. Sarkar worked hard to promote art and art history. He organised demonstration classes by well-known artists with the aim of providing the students with necessary exposure to new techniques and methods of painting. He promoted new artistic practices while encouraging young students to take heed of art history. He also organised a lecture series by eminent art critics, and every Saturday, he showed the students documentaries on Indian art history and films on the art traditions of different countries around the world.

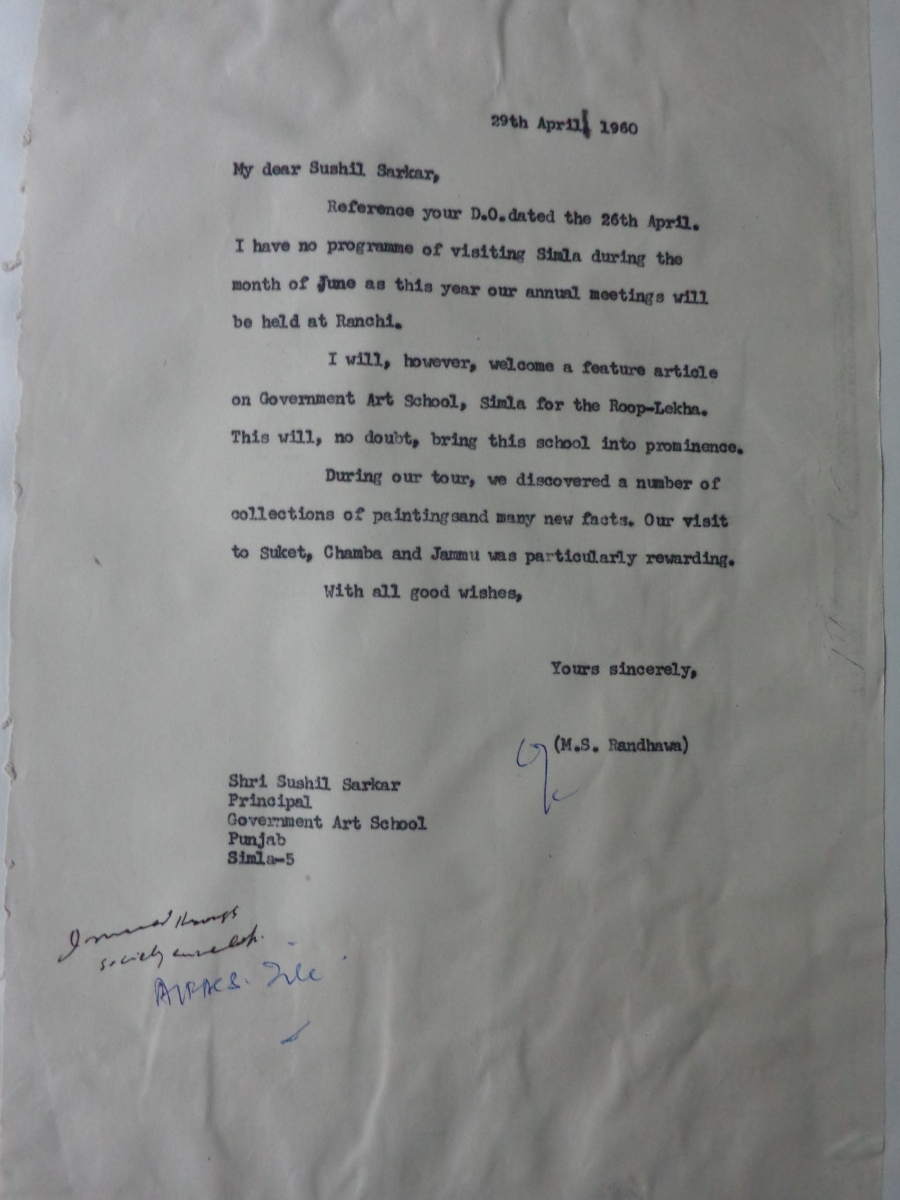

Sarkar’s vision for the development and expansion of the school is evident in the letters he wrote to M.S. Randhawa, the then vice president of Indian Council of Agricultural Research, New Delhi, editor of All India Fine Arts and Crafts Society, New Delhi, and a staunch supporter of art and culture in the northern part of the country. In a letter addressed to M.S. Randhawa, dated April 29, 1960, Sarkar invited him to give a lecture on Basohli or Kangra paintings at the school. He also requested Randhawa to write an article about the school, which he intended to publish in an art journal named Roopa-Lekha. Sarkar had already published about the school in other journals such as The Illustrated Weekly of India and Advance in a bid to increase awareness about the school both among art lovers as well as the common populace.

A letter from M.S. Randhawa to Sushil Sarkar, April 29, 1960. Courtesy: M.S. Randhawa Archives in the Library of Government Museum and Art Gallery, Chandigarh.

In 1962, with the establishment of Chandigarh as the new capital of Punjab, the art school was shifted from Shimla to be the state’s new capital. Even after the reorganisation of Punjab into Haryana, in 1966, the college remained in Chandigarh and came under the aegis of the Chandigarh administration. The name of the institution was changed from the Government School of Arts, Punjab, to the Government College of Art and Craft, Chandigarh (presently, the Government College of Art). This school was the only art institution in the city at the time that catered to a heterogeneous artistic sensibility and inculcated a fresh approach in artists, influenced by the adjoining three states—Punjab, Haryana, and Himachal Pradesh. The teachers and students of this college played an important role in improving and nourishing the art scene of North India.

References

Bhattacharya, S.K. 1994. Trends in Modern Indian Art. New Delhi: MD Publications.

Mago, P.N. 1991. ‘The Future of Visual Art: A Critical View’ Solids: A Monthly Art Bulletin: 8–14.

———. 2001. Contemporary Art in India: A Perspective. National Book Trust, New Delhi,

Mitter, Partha. 2007. Art and Nationalism in Colonial India 1850–1922: Occidental Orientations. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Neville, Pran. (1993) 2006. Lahore: A Sentimental Journey. New Delhi: Penguin.

Sadwelkar, Baburao. n.d. ‘Contemporary Art’, Marg XXXVI: 65.

Sanyal, B.C. 1980. ‘First Amrita Sher-Gil Memorial Lecture.’ Lecture delivered at the Auditorium of Government Museum and Art Gallery, Chandigarh, March 6 to 8.

Srivastava, R.P. 1983. Punjab Painting: Study in Art and Culture. New Delhi: Abhinav Publications.