Though Eid postcards might seem obsolete today, they emerged as popular vehicles of cross-cultural iconography in the mid-20th century, and were posted across continents as Eid greetings. While most of these cards showcased Western iconography and visuals, Urdu poetry was often printed on them to give them an Islamic touch and make them suitable for the festival. We take a look at these relics from the early 20th century and their centrality to Eid celebrations. (Photo Courtesy: Priya Paul Collection, New Delhi/Tasveer Ghar)

In the 1970s and 1980s, film-maker Yousuf Saeed would regularly visit the Urdu Bazaar opposite Jama Masjid in Old Delhi ahead of Eid. He would go with his parents to buy visually attractive Eid postcards from the 25-odd temporary shops jostling for space on the street. They would then write short greetings and salutations for friends and family across the world, and in return, the postman would start bringing a rich and colourful harvest of Eid cards from the other end as well.

Also Read | Ramzan: Some Lesser Known Practices and Rituals

Around 40 years later, navigating through the labyrinthine by-lanes of Chawri Bazaar, repeated enquiries for Eid cards are mostly met with blank faces or negative headshakes from the plethora of wedding card sellers that now dominate the area around Jama Masjid. Urdu Bazaar itself has been reduced to just a couple of shops. It is only after about 45 minutes of asking every other shopkeeper that someone mentions Gali Satte Wali might have some Eid card sellers.

I find one.

Six packets of Eid cards sit tidily at a lone shop in Gali Satte Wali’s Ishwar Market. The shop assistant, Mohan, tells me each card costs Rs 10.50 wholesale and Rs 30 retail. ‘There was a time when we used to get 50 designs of just Eid cards but it has fallen vastly over the years, and for the past two years it’s just been really low, mainly because of WhatsApp and email, so we’re just doing six designs now,’ laments P.R. Ray, the owner of Signature Cards Shop. He adds that exports to Srinagar, Assam, and Kerala mainly drive the sales of his Eid cards; the numbers can’t hold a candle to the lakhs of Valentine’s Day cards he sells every year.

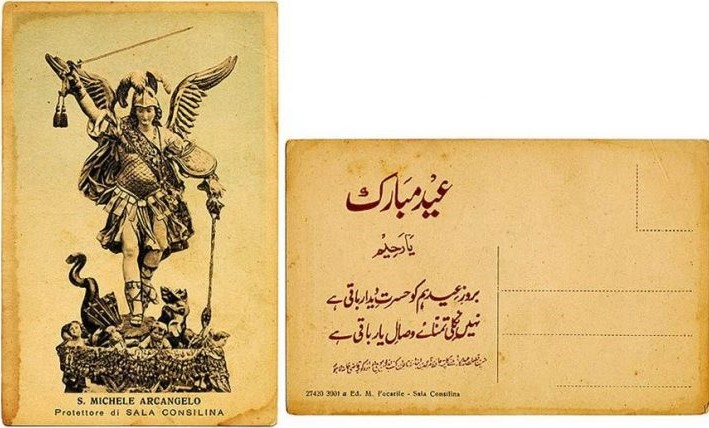

In today’s Digital Age, when even SMSes are becoming obsolete, handwritten messages by post have become a rarity (Courtesy: Imagesofasia.com/Tasveer Ghar)

Big corporations such as Archies Ltd, who also sell Eid cards, have not been as acutely hit by people’s shift to digital mediums. ‘This has always been a niche market for us, so the consumption has been stable over the past 20–25 years. We still print a set of 8–10 new designs every two years. But yes, overall the cards market has suffered a huge deal because of WhatsApp, SMSes and emails,’ says Youhan Aria, Head, Corporate Communications, Archies Ltd.

In today’s digital age, when even SMSes are becoming obsolete, handwritten messages by post have become a rarity not only in India but even in countries such as Pakistan, where people question the expense of Rs 40–50 for a single card, plus postage, when a WhatsApp image costs nothing. ‘Why should I purchase a Rs 50 Eid card? I have my cell phone and laptop to greet my friends and relatives on Eid,’[i] Sohail, a resident of Sabzazaar colony in Multan tells Pakistan’s UrduPoint.com in an article on e-culture drowning the Eid card tradition.

Also Read | Eid in Malabar, Kerala

Saeed, co-founder and director of Tasveer Ghar—a digital archive of South Asian popular visual culture—has himself not sent an Eid card in years. But that did not deter him from researching and writing an exhaustive essay on the culture for his website, which has digitised hundreds of postcards from various collections. The 50-year-old has tried to document the early days of Eid cards in South Asia, especially to see ‘how they emerged as popular vehicles of iconography across cultures via the postal networks’. Going through the archival collections of Priya Paul (Chairperson of Apeejay Park Hotels), Reena Mohan (film-maker), Omar Khan (author of Paper Jewels: Postcards from the Raj) as well as his own, he found out that older Eid postcards were more European in design, and Islamic symbolism intensified in the latter part of the 20th century and early 21st century, an observation corroborated by Archies’ Aria.

From Christmas to Eid

It is assumed that while Christmas postcards started appearing towards the end of the 19th century in Europe and America, the earliest known cards with Indian visuals or cards made in India date back to around the 1900s. These were mostly postcards with Indian ‘native views’ to cater to European recipients. Paul’s extensive collection interestingly shows that the earlier Eid cards—from the 1930s—did not necessarily carry Islamic images, but seemed to be inspired by Christmas greeting cards. An example would be of an aeroplane showering gifts on children, which is strikingly reminiscent of Santa Claus.

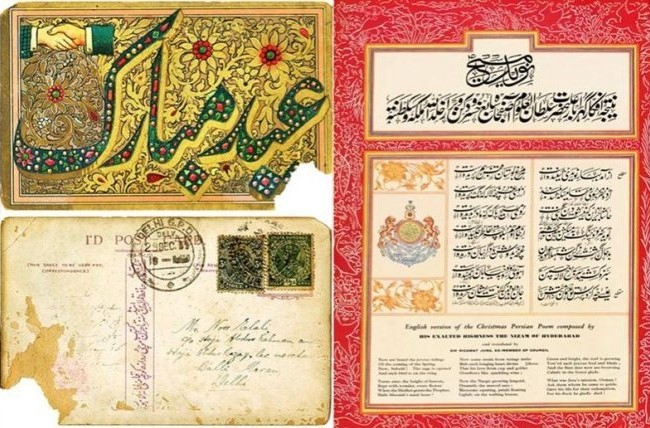

In the late 1800s, Mahboob Al Matabah in Delhi and Bolton Fine Art Lithographers in Bombay were some of the earliest companies that came into the business of printing Eid cards (Courtesy: Priya Paul Collection, New Delhi/Tasveer Ghar)

It is not that people were not sending Eid greetings before the Christian influence. Sometimes children would send greetings messages and would be rewarded with gifts or money in return. Saeed’s essay[ii] quotes Delhi journalist Asad Kidwai, who says these messages were originally called Eidi. And even maulvis (Islamic scholars) wrote such messages of prayers and well wishes for the rich Muslims, and they were presented with gifts and money in return.

But these were personal missives. The need for more mass mailing came in with migration to other parts of the country and world. This practice was facilitated by the advent of printing technology and, from the 19th century on, by the expansion of the railway network as the dependence on Mughal-era daak chowkis (postal stations) reduced.

Also Read | A Ramzan in Peshawar

In the late 1800s, Indian companies such as H.A. Mirza (Delhi), Gobindram Oodeyram (Jaipur), Rewachand Motumal & Sons (Karachi), Melaram (Peshawar) and Johnny Stores (Karachi) began printing picture postcards. But these were more for the European consumer. A 2015 Dawn article says, ‘Hafiz Qammaruddin & Sons, H. Ghulam Muhammad & Sons and Muhammad Hussain & Brothers in Lahore, Mahboob Al Matabah in Delhi, and Eastern Commercial Agency, Shabbar T Corporation and Bolton Fine Art Lithographers in Bombay were amongst the earliest companies that came into the business of printing Eid cards in the Indian subcontinent. Postcards with Indian Muslim architecture, produced by Raphael Tuck in London, were also used for Eid.’[iii]

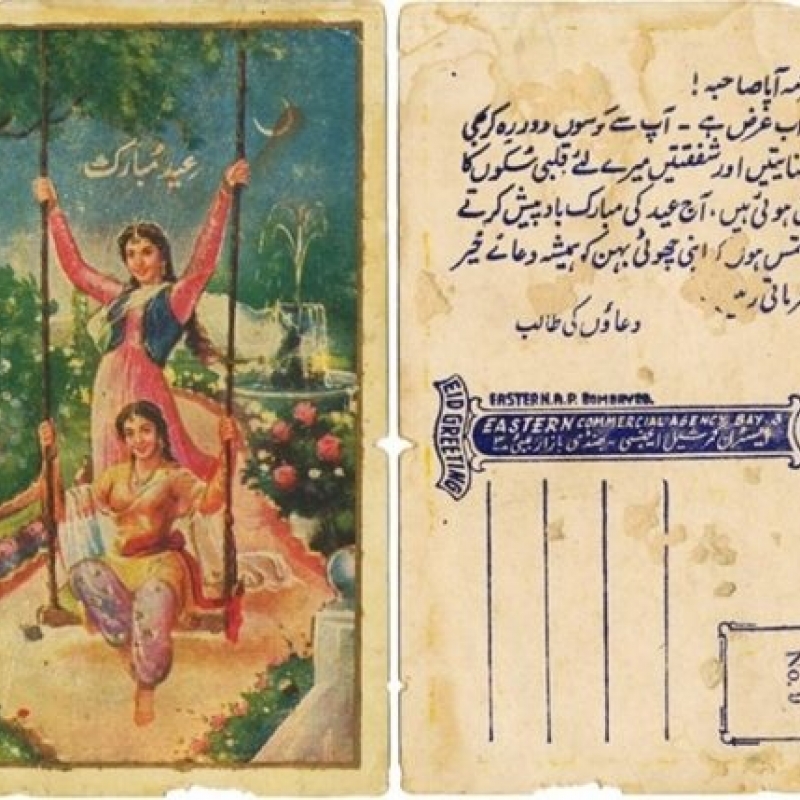

While the visuals were still Western, the addition of Urdu poetry and verses would add the Eid touch. Paul’s collection has many used and unused Eid cards from the 1930–40s in Lahore, which feature images imported from Europe, stamped with messages of Eid greetings in Urdu. Saeed speculates that it could have been that postcards were imported in bulk from Europe and then stamped with Urdu/Arabic phrases ‘Eid Mubarak’ or ‘assalamu alaikum’ (salutation) on the front and poetic messages at the back to make them suitable as an Eid greeting.

But often these images would be carefully chosen. For instance, in one card, a poetic reference for Eid greetings between ashiq (lover) and ma’shuq (beloved) is made for a photograph of an unidentified European dancer/actress; an Urdu couplet for a portrait of a smiling young Caucasian woman starts with the line ‘When I saw (her) eyebrows, I could imagine the Eid crescent…’ Other cards would feature Indian actresses and even women who would not conform to the stereotyped ‘pious Muslim look’.

While the visuals were still Western, the addition of Urdu poetry and verses to the postcards would add the Eid touch (Courtesy: Priya Paul Collection, New Delhi/Tasveer Ghar)

Another example of the migratory influences would be the inclusion of sailing ships in many cards—a motif prevalent in the 20th century—which could have multitudes of meanings, from ‘messages from overseas’ to a desire of travel to meet someone on Eid, or even a pilgrimage, explains the essay. Among the collections found, there were several that seemed to have Turkish influences as well, with a prominent depiction of the crescent moon in Urdu verse as well for symbolism. This includes the crescent and star icon that has been Turkey’s national symbol. The crescent and the star mark has been appropriated as Eid iconography as a sign of the sighting of moon, explains Saeed, adding several examples of repurposing other ‘native view’ cards—such as Jama Masjid of Delhi, Lahore’s Badshahi Mosque or the Shrine of Salim Chishti—by printing Urdu couplets or Eid Mubarak messages by Indian printers.

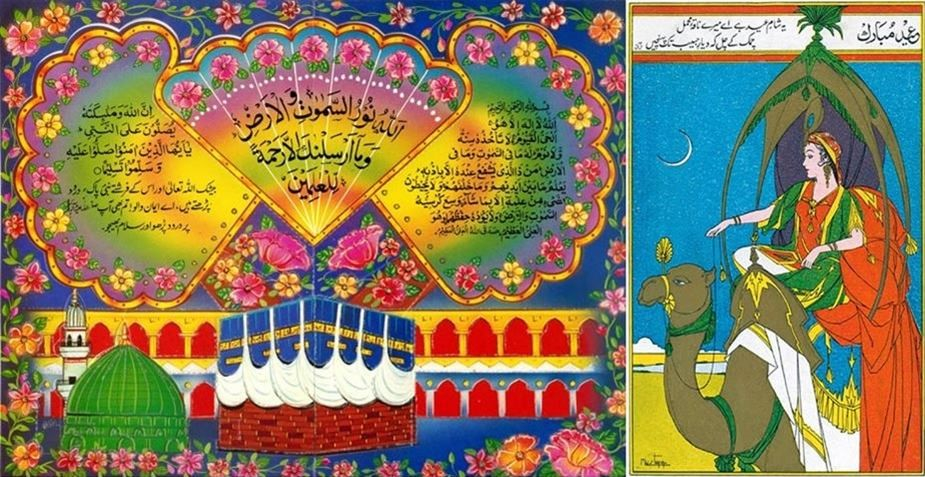

Intensification of Religious Icons on Eid Cards

Saeed admits there is a gap in his research between the 1950s and 1980s, but he did notice a growth in the use of religious icons in the late 1980s onwards. These included images of Mecca, Medina, Quranic calligraphy, crescent-and-star icons, pious praying women and babies, and occasionally, romantic rose bouquets. Aria agrees, saying, ‘the crescent moon and calligraphy are typical of Eid cards’, though now there has been an increase in embellishments such as glitter and embossing as well. One reason for this, Saeed says, could be the transition of these greetings from postcards to folded cards that would need to be enclosed in an envelope, which would avoid direct touch. ‘Since postcards are sent openly without an envelope and are hence possibly exposed to being treated in a disrespectful manner. Even the touch of non-Muslims on a card’s postal journey would have been sacrilegious. I noticed that almost all Eid cards using the sacred icons of Mecca and Quran etc. are large folding cards to be sent necessarily sealed in an envelope, and mostly produced more recently than in the early 20th century,’ he writes.

Also Read | Eid ul Fitr

Though for the Delhi-based card-maker P.R. Ray, the shift has been from darker colours and iconography to more roses and floral prints in Chawri Bazaar, ‘because then I think non-Muslims feel more comfortable to give it to their Muslim friends… they’re also popular in the Middle East’.

While the Internet gets clogged with well-meaning wishes thanks to cheerful Indians every day, and on every occasion with more and more websites offering electronic cards and images to be circulated en masse, some even accompanied with music and prayer recitations, there is no denying that many miss the tangibility of touch and personalised notes that would turn an otherwise generic card into a keepsake.

This article was also published on The Statesman.

Notes

[i] Sumaira F.H., ‘Tradition Of Eid Card Greetings On Decline’, Urdu Point, Pakistan, May 23, 2018, accessed July 9, 2019, https://www.urdupoint.com/en/pakistan/tradition-of-eid-card-greetings-on-decline-351377.html.

[ii] Yousuf Saeed, ‘Eid Mubarak: Cross-cultural Image Exchange in Muslim South Asia,’ Tasveer Ghar India, n.d., accessed July 9, 2019, http://www.tasveergharindia.net/essay/eid-image-exchange-muslim-southasia.html.

[iii] Aown Ali, ‘The lost art of Eid greeting cards,’ Dawn, Karachi, June 4, 2019, accessed July 8, 2019, https://www.dawn.com/news/1193787/.