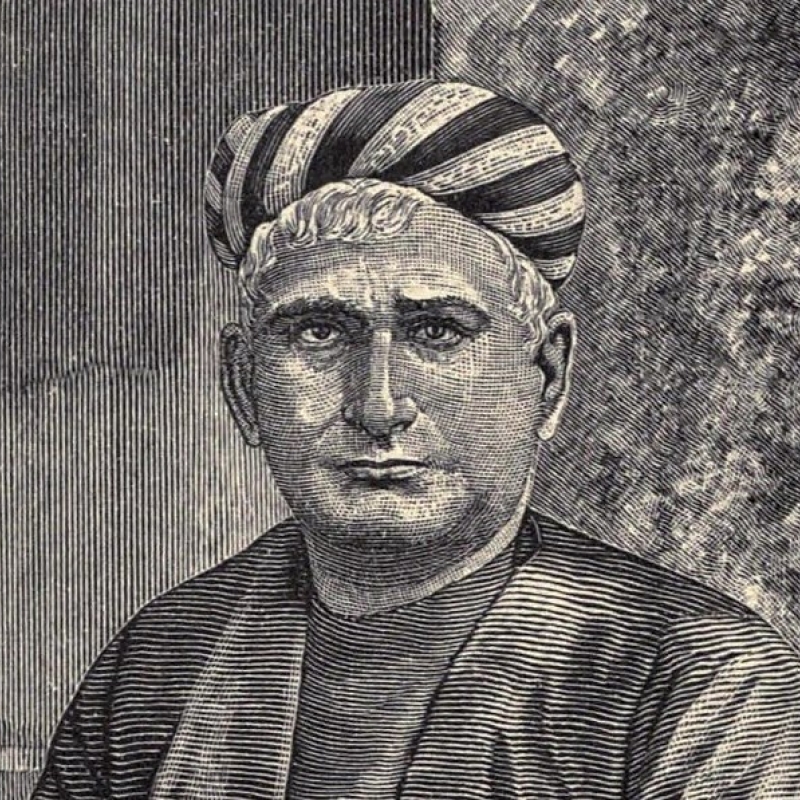

Unknown to many, novelist Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay also devoted considerable attention to popularise science through a number of essays. Interestingly, he felt that it was European science that had ultimately conquered India for the British. We look at Chattopadhyay’s scientific philosophy. (Photo Courtesy: Romesh Chunder Dutt [Public Domain])

We all know Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay for producing highly popular and entertaining novels in Bengali. However, his literary genius served to somewhat distract and hide from public view other equally important and productive facets of his intellectual and cultural life. That Chattopadhyay devoted considerable attention to history, anthropology, sociology, religion and popular science, is a fact seldom acknowledged. Of these, the last is clearly the most neglected.

In 1994, a commemorative volume (Bankimchandra: Essays in Perspective) of 650 pages edited by Bhabatosh Chatterjee attempted to critically reassess Chattopadhyay’s life and work but did not include a single essay on his approach to science and scientific thought. This, notwithstanding the fact that he produced a collection of nine Bengali essays on elementary science, first published in 1875 as Vigyanrahasya (Mysteries of Science) and reprinted in his lifetime in 1884. Chattopadhyay also articulated a philosophy of science through which he attempted to understand not only its technical functions or properties but also the social and intellectual.

His writings on popular science coincided with his entry into the world of Bengali journalism. It is for his monthly journal Bongodarshan (founded in 1872) that he began writing these essays. The aim was to popularise science among interested men, schoolboys of advanced levels and educated, modern women. Importantly, Chattopadhyay was also among the first to support Dr Mahendralal Sarkar in his attempts to establish the Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science (he writes about this in his essay Bharatvarshiya Vigyan Sabha, 1872. Three years later, the association was founded).

The essays written for the Bongodarshan between 1872 and 1875 were essentially adaptations from the writings of European scientists, who lived and worked between the 17th and 19th centuries. This includes the Italian Evangelista Torricelli, Frenchman Blaise Pascal, Scotsman Charles Lyell, the Irish John Tyndall and Englishmen T.H. Huxley, Norman Lockyer and Richard A. Proctor. Between them, these men had covered the scientific disciplines of biology, mathematics, astronomy, physics, geology and anthropology, which also exhibit the breadth of Chattopadhyay’s intellectual engagement with science.

His essay ‘Dhula’ (Dust) is based on Tyndall’s ‘Dust and Disease’, ‘Jaibanik’ (The Protoplasm) on Huxley’s ‘Lay Sermons’ and ‘Goto Kaal Manushya’ (Antiquity) on Lyell’s ‘Geological Evidence of the Antiquity of Man’. Since his vocation as a civil servant took him to places far away from the colonial metropolis of Calcutta, these essays were written, as Chattopadhyay confesses, under trying conditions, without the support of suitable libraries to borrow books or the discerning reader. And yet, as expressions of an honest curiosity about scientific phenomena, these are simply sparkling in their depth and originality.

Chattopadhyay believed that proper use of science would help Indians to dismantle their settled opinions, irrationalities and superstitions (Courtesy: Srijeet1988 [CC by-SA 3.0])

Science as Philosophy

Colonial Bengal’s interest in popular science did not originate with Chattopadhyay. It is anticipated in the works of the two foremost educationists of his time: Akshay Kumar Dutta and Iswarchandra Vidyasagar. Dutta’s Charupath (three parts, 1853–59) and Vidyasagar’s Bodhodoy (1851) were useful, school-level primers. While the driving force in Dutta and Vidyasagar was essentially pedagogic, Chattopadhyay preferred to treat the subject more philosophically. In an 1873 essay, ‘The Study of Hindu Philosophy’, he investigated the typically Hindu approach to science and, more broadly perhaps, the Hindu’s intellectual predilections. The Hindu approach, he faulted on account of adopting the wrong investigative method; he thought it relied more on a deductive rather than an inductive approach based on empirical observation and experiment. In his essay ‘The Study of Hindu Philosophy’ (1873), he wrote, ‘A Hindu philosopher in Torricelli's place would have contented himself with simply announcing in an aphoristic sutra that the air had weight... no experiment would have been made with the mercury; no Hindu Pascal would have ascended the Himalayas with a barometric column in hand.’

In this essay, he cited the example of how physicists such as Torricelli and Pascal seized upon the observations once made by the gardeners of Florence that the water column would not rise above a certain height, even when boosted by a water pump. This eventually led them to the theory of atmospheric pressure. He was also disheartened to note how Indians would not energetically push their scientific observations to their logical conclusions. Aryabhatta’s astronomical or mathematical observations, though arriving several centuries before the advent of modern science, were left fuzzy and ill-defined since they were formulated in the typically aphoristic (sutra) style prescribed by the Indian tradition.

Chattopadhyay felt that it was European science that had ultimately conquered India for the British, and his argument here was that a continuing indigenous tradition of scientific study would have actually served the people far better instead of leaving them irrational and indolent. It is important to realise that Chattopadhyay also used science and reason interchangeably, which then allowed him to make critical remarks relating to Hindu society and culture. This emboldened him to say how Puranic gods such as Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva were but fictional characters. In ‘Trideb Sombondh Vigyanshastra Kee Bole’ (What does Science Have to Say About the Trinity, 1875), he wrote, ‘The apocryphal tales occurring in our Puranas and itihas [history] do not have any scientific argument behind them. Brahma, Vishnu, Maheswara and similar other gods are but characters from some strange novels.’ In ‘On the Origin of Hindu Festivals’ (1869), he stated how several Hindu festivals that had acquired a religious character over time were originally linked to agrarian production cycles.

For him, science constituted the very edifice of reason and realism, and its proper use, he believed, would only help Indians to dismantle their settled opinions, irrationalities and superstitions. In a concluding note to ‘Chandraloka’ (in Vigyanrahasya), his essay on the moon, he tells us how literary imagination could never catch up with science. Literature often created a comforting, make-believe world whereas science hastened to demolish it.

This article was also published on The Wire.