Introduction

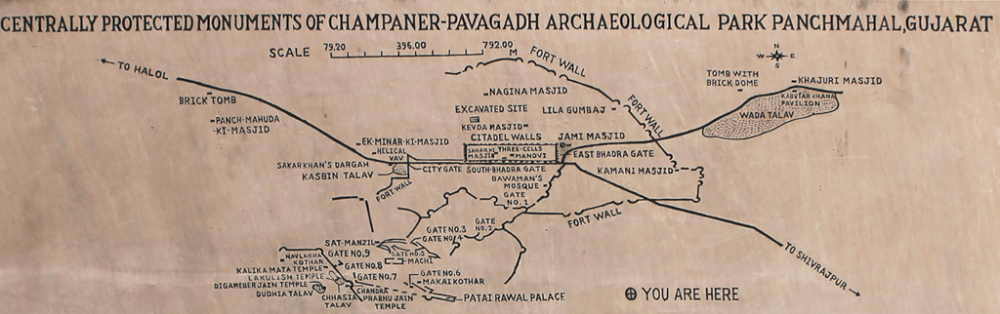

The city of Champaner and the hill of Pavagadh lie 45 kilometres to the north-east of Vadodara and 42 kilometres to the south-west of Godhra in the Panchmahal district. The city of Champaner is sprawled over six square kilometres near the foot of the Pavagadh Hill, which rises peculiarly about 800 metres in a predominantly plain region. In 2004, UNESCO conferred the World Heritage Site tag to the Champaner-Pavagadh site during its 28th session held in Suzhou, China. The entire archeological complex of Champaner and Pavagadh is home to religious structures of Hindu, Jain and Muslim communities along with fortresses, fortifications, palaces, agricultural structures, water-harvesting installations among others. The monuments fully blend Islamic with other architectural styles, and the city of Champaner is the only complete and standing pre-Mughal Islamic city in India.

Origin of Nomenclature for Champaner and Pavagadh Hill

There are two hypotheses regarding the origin of the names, Champaner and Pavagadh. The geographically inclined theory points towards the light yellow and red pigmentation of the igneous rocks of the Pavagadh Hill which are often compared to the ‘Champaka’ flower or that resemble the flames of fire from which are derived the name Champaner for the town and Pavagadh for the hill. The alternative theory that finds its basis in the social and political history of the region claims derivation of the nomenclature from two political figures—‘Champa’, a minister of King Vanaraja, a ruler of the Chavada dynasty of Gujarat, and a headman of the Bhil tribe residing in the vicinity who was also named ‘Champa’.

Literary References to Champaner and Pavagadh

The 12th-century drama, Prithviraj Raso, by Chand Bardai contains references to Pavagadh as ‘Pavakgadh’, meaning fire hill, and as ‘Pavangadh’, meaning wind hill, while mentioning Ram Gaur Tuwar as its ruler. The Champaner and Pavagadh region is also described in Persian literary sources such as Mirat-i-Sikandari by Sikandar Bin Muhammad, Ain-i-Akbari by Abul Fazal, and Tabqat-i-Akbari and Tarikhi Farishta by Muhammad Qasim. The Gangadasa Pratap Vilasa Natakam and Garba of Kalika dramas of Sanskrit and Gujarati literature respectively also make references to Champaner and Pavagadh. According to the legends of Shakti Peeth, it is believed that the Pavagadh Hill is the location where the toe of Goddess Sati fell, or that the the Pavagadh Hill is in its actuality the toe of Goddess Sati.

View of Kali Temple from Rani no Mahal

Archeologist James Burgess and historian Henry Cousens also studied Champaner but only from the perspective of its religious structures, especially the Jami Mosque, Kevada Mosque and Nagina Mosque. Hermann Goetz, a German scholar, also undertook research on Champaner and attempted to map the city and its vicinity.

History

Archeological findings claim that the region in and around Champaner has been inhabited by humans since prehistoric times. Stone tools found in the Jorvan tributary of the Dhadhar river which originates from the Pavagadh Hills are said to belong from the Lower and Middle Paleolithic periods. Further excavations in the Bhadrakali Valley and Visadi regions and its findings link the area to Mesolithic and Upper Paleolithic periods.

The earliest historical sources recovered relate to the Maitraka dynasty which ruled the region in 470–776 CE. The discovery of two silver-coated copper coins along with other remnants add further support to this date. Another source confirming the Maitraka rule around Champaner are the Kapadvanj copper plates of Dhruvasena III from 653 CE, which state that the Maitrakas ruled over Shivabhagapura, identified today as the town of Shivrajpur, situated in the vicinity of Champaner and Pavagadh Hill.

The region of Champaner and Pavagadh was an important junction connecting Gujarat to Malwa, which made it an important asset for political reasons, for its economic benefits and for those with military aspirations. For any ruler who wished to conquer Malwa, control over Champaner and Pavagadh was most essential. This is evident from the number of dynasties, such as the Gurjara Pratiharas, Rashtrakutas, Paramaras of Dhar, and the Chalukyas of Anhilwad Patan, who have captured this area or attempted to.

The Khichi Chauhan Rajputs from Mewar are said to have subjugated Pavagadh and Champaner in around 1300. This is authenticated by the discovery of an inscription found in a stepwell near Nahani Umarvan near Champaner. The inscription gives a complete genealogy of the rulers of the Khichi Chauhan Rajputs—a total of 13 rulers from Ramadeva to Jayasimha, of which the fifth ruler, Palhansila, is said to have established Khichi Chauhan rule over Champaner and Pavagadh. The inscription further adds that they belong to the lineage of Prithviraj Chauhan. The Khichi Chauhans were the undisputed rulers of the Champaner-Pavagadh region until Mahmud Begada, the Sultan of Gujarat, defeated the last of the Khichi Chauhan rulers in 1484.

The Gujarat Sultanate made several attempts to capture Champaner and Pavagadh from the Khichi Chauhans. Sultan Ahmed Shah I made two unsuccessful attempts to invade Pavagadh, which was then being ruled by King Trimbak Bhupa, in 1418 and 1431. Again, in 1450, Sultan Muhammad Shah II, the son and successor of Ahmed Shah I, laid siege to Champaner and Pavagadh, which was under the suzerainty of King Gangadas, the son of King Trimbak. King Gangadas fought bravely during the initial conflict but later was forced to seek aid and assistance from his trusted ally—Sultan Mahamud Khilji, the ruler of Malwa. As a result of Khilji joining forces with Gangadas, Muhammad was forced to retreat. This conflict found its place in the contemporary literature of the time. The Sanskrit drama Gangadasa Pratapa Vilasa Nataka which was authored by court poet Gangadhara mentions not just the conflict but also describes the fort of Pavagadh. Following the aspirations of his grandfather and father to capture Pavagadh, Mahmud Shah I, the Sultan of Gujarat, laid siege to Champaner-Pavagadh between April 1483 and December 1484. The 20-month siege ended with the defeat of Pitati Rawal Jai Singh, the last Rajput ruler, and the transfer of control over the coveted region to the sultans of Gujarat. The seizure of Champaner-Pavagadh was for Mahmud essential to achieving his military designs against Malwa. Towards this end, Mahmud decided to shift his capital from Ahmedabad to Champaner. The Sultan of Gujarat renamed Champaner as Mahamadavada, also referred as Muhammadabad. In recognition of his capture of two important forts of Gujarat—Girnar-Junagarh and Champaner-Pavagadh—Mahmud was conferred the title ‘Begada’, ‘Be’ meaning ‘two’ and ‘Gada’ meaning ‘fort’ in Gujarati. An epigraphic source in the form of a stone inscription in Nagari script dated Vikram Samvat 1554 (1498 CE) discovered in a stepwell at Mandvi near Champaner throws light on the foundation of the new capital city. Mahmud Begada patronised several development projects in Champaner to turn the city into a worthy capital. Apart from civil, military and religious structures, the Sultan of Gujarat decreed the construction of new roads, fortifications, bridges, gardens and water harvesting installations among others. Under the rule of Mahmud Begada, Champaner, in its new role as the capital of Gujarat, witnessed its most prosperous period.

The 16th century saw a change in the political scenario in Delhi, with Babur defeating Ibrahim Lodi, the last ruler of the Delhi Sultanate, at the First Battle of Panipat in 1526, and establishing Mughal rule in north India. After his defeat in the Battle of Kanauj (1540) against Sher Shah Suri, Humayun, the deposed Mughal ruler, attacked Champaner in 1534 during the reign of Sultan Bahadur Shah of the Gujarat Sultanate. Humayun was drawn by the wealth of Champaner and decided to attack and plunder it, probably in order to fund his campaign to regain his lost seat on the coveted throne of Delhi. The attack by Humayun struck a significant blow to the legacy of Champaner as it ushered in a period of decline. The Gujarat Sultanate thereafter reshifted its capital to Ahmedabad. Champaner then witnessed a succession of new conquerors—Mahmud III who captured Champaner during the rule of Mughal Emperor Akbar, followed by Shah Mirza; Krishnaji Kadam, son of Kantaji Kadam Bande, captured it in 1727; later the Scindias of Gwalior controlled Champaner, and finally relinquished control of the terrain to the British in 1853. The decline of Champaner is documented in the Persian literary chronicle Mirat-i-Sikandari, written during the reign of Mughal Emperor Jahangir, which describes how everything lay in ruins apart from the royal citadel or Hissar-i-Khas in Champaner and Machi area on Pavagadh Hill.

Archeological Excavations

In independent India no excavation had been carried out on a site from the medieval period until 1969, when the Department of Archeology and Ancient History of The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, under the guidance of archeologist Prof. R.N. Mehta, undertook the task of conducting excavations at Champaner and Pavagadh. Excavation work continued at the site till 1977. The initial surveys of the former capital of medieval Gujarat aided in understanding the dynamics of city planning in addition to contributing towards further study of the social, political and, especially, religious complexities of Champaner and Pavagadh. The focus of the excavation was to discover and understand the urban identity of Champaner.

A view of Amir Manzil

The excavations revealed that the royal citadel, colloquially known as Hissar-i-Khas or Jahapanah, was at the centre of the entire complex. The Amir Manzil was identified as the place of residence for the royalty. The complex was well fortified with walls despite which the city stretched from Vada Talao to Halol town. The fortifications reveal that Champaner may have served the dual role of state capital and military stronghold, to secure itself from probable invasions, especially given its proximity to the kingdom of Malwa. The religious structures, particularly the mosques, were built at crossroads connecting the residential areas to the commercial zones. The Shahar-ki-Masjid was the private mosque for the royalty. Several commemorative structures such as mausoleums or makbaras are also found in and around the city, such as the tombs of Sakar Khan and Sikandar Khan. An interesting element of the entire complex was the many water harvesting installations in the form of lakes, ponds, wells, stepwells, tanks, etc., among which the helical stepwell stands out. The military structures, though not excavated entirely, are believed to have been situated well outside the city limits beyond Vada Talao. The remnants of old catapults near Atak Gate on Pavagadh Hill shed light on the military stratagy. The Champaner complex also housed structures catering to civilian needs, such as sarais (lodging or rest house), markets, bridges, kabrasthans (graveyards) among others. The Kabutarkhana (Bird House) situated near Vada Talao and Khajuri Mosque was a royal leisure house overlooking the lake and the Pavagadh Hill. The presence of structures relating to leisure activities and beautification completed the entire set-up for Champaner.

Atak Gate

The plan to conduct excavations at Champaner and Pavagadh was part of a national project funded by the University Grants Commission to undertake excavations at three major national sites. This was the first instance in independent India of a study of a medieval site from an archeological perspective. The other two sites were Fatehpur Sikri and Hampi.

Monuments

- Jami Masjid

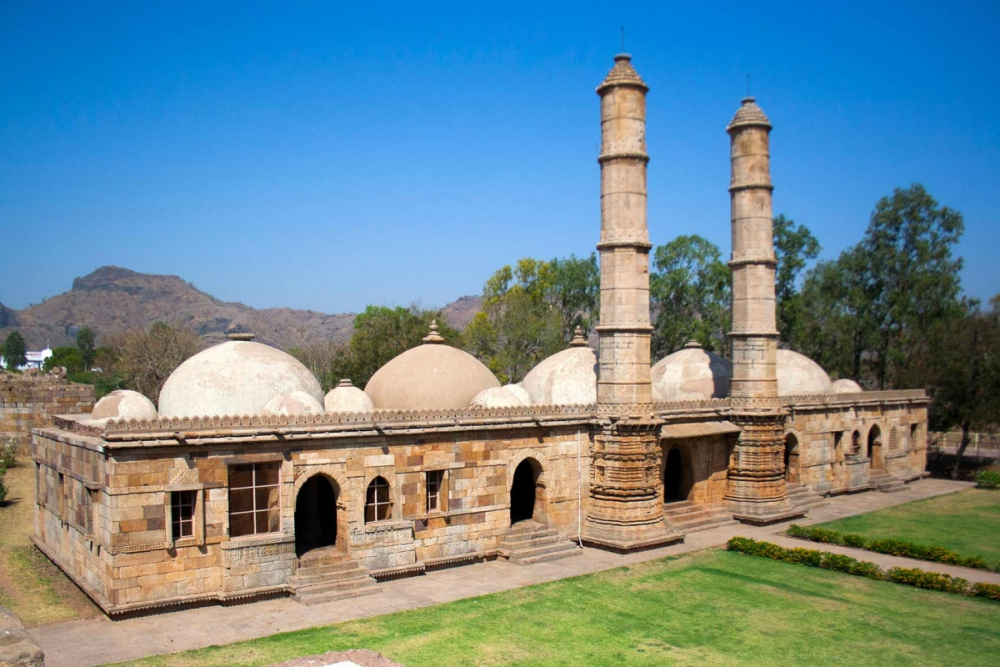

The most alluring monument at the Champaner-Pavagadh site is the Jami Masjid, considered one of the most beautiful mosques in Gujarat. The mosque is one of the finest examples of the Indo-Islamic school of architecture. The intricacy of carving, perforated stone screen works, classical Gujarati style balcony-windows, its 172 pillars supporting the central dome, the seven mihrabs (prayer niches) and its imposing minarets are just among the many exceptional attributes of the Jami Masjid. There is an ablution tank named Hauz-a-Vazu in the mosque complex as well. Afflixed to the central mihrab in the Jami Masjid was an inscription which stated the date of completion to be 914 in the Hiziri Era, equivalent to 1508–09 CE. Unfortunately, the inscription is no more there.

Jami Masjid

- Other Mosques in Champaner

The entire complex of Champaner-Pavagadh site is home to several majestic and intriguing mosques. Among all the mosques, the Jami Masjid clearly stands apart. The other mosques in Champaner are described below.

The Shahar ki Masjid near the North Bhadra Gate was the private mosque for the royal family, and has five mihrabs, while the entrance is flanked by two impressive minarets.

Shahar ki Masjid

The Nagina Masjid was built on a high plinth housing three mihrabs, with the central arched entrance flanked by intricately carved minarets. The Nagina Masjid contains artistic wall carvings, especially floral patterns. The mosque has three domes, 80 pillars, 10 cupolas and jharokha windows. The Nagina Masjid complex also has a well and a cenotaph, which is very intricately carved.

Nagina Masjid

The Kevada Masjid is another mosque built by incorporating intricately carved pillars, minarets, niches and windows. The Masjid has a two-storeyed prayer hall. The central dome of the mosque has collapsed.

Kevada Masjid

The Lila Gumbaj-ki-Masjid is built on a high plinth. The mosque has three entrances constructed using the trabeate system. The arched central entrance is flanked by minarets on each side. The mosque yet again has very intricate carvings, especially floral, pot chain and foliage motifs, in its niches, on minarets, and its three mihrabs.

The Ek Minar Ki Masjid was built by Bahadur Shah in 1526–35. The mosque gets its name from its lone standing minaret, which has five storeys.

Ek Minar ki Masjid

- Amir Manzil

Amir Manzil was the main residential complex of the royal family of Champaner. It was discovered during the excavations conducted by the Department of Archeology and Ancient History, MSU. The Amir Manzil complex comprised residential quarters, gardens, tanks, stables, water channels, cisterns and spiral water channels among others. The complex was probably utilised as living quarters for over a century, based on the findings of the excavations. The antiquities which were excavated at the Amir Manzil complex ranged from ceramic, terracotta and stone to iron, copper and silver items. The excavation has also recovered remnants of Chinese porcelain ware along with a single silver ring and coins.

- Water Harvesting Structures

The region of Champaner-Pavagadh was known for its shortage of water. Towards mitigating this, several water-harvesting techniques were employed at the site. There are several natural talaos (ponds) such as Medi Talao in Atak area, Tailia Talao at Machi, and Dudhia, Chasia and Naulakhi talaos at the Mauliya Plateau. There are three kunds on Pavagadh Hill named after the famous rivers of India, Ganga, Yamuna and Saraswati. The stepwells were created to cater to day-to-day needs. The helical stepwell, built in the 16th century, is the best example. The water structures symbolised religious, social and political development and were considered an important aspect of architecture during those times. The city of Champaner is also known as the ‘city of a thousand wells’.

Hellical Stepwell

- Saat Kaman

The bastion of Saat Kaman is located on the Pavagadh Hill between the Sadan Shah Gate and Budhiya Darwaja. The colloquial disambiguation of the name Saat Kaman is ‘Saat’ meaning seven and ‘Kaman’ meaning arches. The structure was a military post since the location provided a vantage point on the entire open expanse of land. The structure is interesting due to its unique architecture wherein the yellow sandstone is shaped in a semi-circular pattern in support of the main structure.

Saat Kaman

- Catapults

The hill fortress atop the Pavagadh Hill still shows evidences of a wide range of structures designed for both defence and offence, such as the catapults which stand near the Atak Gate.

Catapult near Atak Gate

- Mint or Tankshala

Mahmud Begada established a mint in 1484. The coins minted here always carried the inscription ‘Shahar Mukarram’ meaning ‘the illustrious city’. Made of silver and copper, the coins were minted here between 1485 and 1537 by Mahmud Begada and his successors—Muzaffar II, Bahadur Shah and Mahmud III. After Humayun attacked the city, he too minted some silver and copper coins. The mint on Pavagadh was one of the four mints of the Gujarat Sultanate. The other three mints were at Ahmedabad, Ahmednagar and Junagarh.

Mint on Pavagadh Hill

- Lakulisa Temple

The oldest temple at the Champaner-Pavagadh archeological park is the Lakulisa Temple, dated around the 10th–11th century and situated on the Mauliya Plateau on Pavagadh Hill. Lakulisa was an ardent devote of Lord Shiva and is credited with having initiated the Pasupata cult of the Shaivas. The chief elements of the Lakulisa Temple are the garbha griha (seat of the main deity), antarala (space where worship is conducted), mandapa (inside porch) along with eight intricately carved pillars. Brahma, Vishnu, Kalyanasundara Murti, Dakshina Murti, Gajendra Moksha, Indra, Ambika, Surasundaris are just some of the many figures of deities carved in the Lakulisa Temple. The iconography of Lakulisa is unique: the idol of Lakulisa is seated in yogasana posture with a yogapatta and a band of cloth around its knee.

Lakulisa Temple

- Kalika Mata Temple

The Kalika Mata temple on the summit of Pavagadh Hill is another important structure of great historical and religious significance. Goddess Kalika Mata was the kuldevi or clan deity of the Khichi Chauhan dynasty which ruled over Pavagadh. The temple has been mentioned in the Sanskrit drama Gangadas Pratap Vilasa Natakam, written during the reign of King Gangadas in the 15th century. The Kalika Mata temple is one of the many shrines devoted to the Mother Goddess across the country. According to myth, the location of the temple is the place where the toe of Goddess Kalika Mata fell. Another variation of the legend states that the Pavagadh Hill is actually the fallen toe of Kalika Mata. The temple of Kalika Mata had a spire on the top of its main structure which has not survived. Adjacent to the temple is the tomb of Sadan Shah Pir constructed in Islamic architectural style, complete with a spherical dome.

- Jain Temples

The Jain temples on Pavagadh Hill date to around the 13th–14th century. The temples belong to the Digamber sect of Jainism which was prominent in Gujarat. The temples are dedicated to Suparshwanath, Chandraprabha and Parshwanath.

Adinath Digambar Jain Temple

Religious and Cultural Significance of Champaner-Pavagadh

The congregation of religious structures at the Champaner-Pavagadh site complex present a clear picture of religious harmony. The oldest structure in the complex is the Lakulisa temple dating back to 10th–11th century, which is dedicated to Lakulisa, the creator of Pasupata cult of Shiva. The Kalika Mata temple is one of the seats of the Mother Goddess in India (Shakti Peeth), which attracts several devotees throughout the year and especially during the Navratri festival. The 13th–14th-century Jain temples belonging to the Digamber sect add to the religious diversity of the region. The wide range of mosques in Champaner are not just impressive but represent a unique collaboration culminating in the Indo-Islamic style of architecture. There is also mention of a church at Champaner. The amalgamation of these cultures and religions gives an insight into the social and political fabric of Champaner and Pavagadh. The religious harmony of the period can be inferred especially from the inscription discovered in a stepwell in Champaner dated around 1498, during the rule of the Gujarat Sultans, which is written in Devanagari script in Sanskrit and medieval Gujarati, and begins with an invocation to Ganesha and Sharada.

References and Further Reading

Joshi, G. 2015. Champaner-Pavagadh Pravas Darshan. Ahmedabad: Chandrika Printery.

Mehta, R. 1979. Champaner: Ek Adhyayan. Vadodara: The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda Press.

Shivananda, V., and A. Bhargava. 2009. Champaner Pavagadh (World Heritage Series). New Delhi: The Director General, Archeological Survey of India.

Sonawane, V. 2009. ‘Excavations at Champaner: A First World Heritage Site of Gujarat’. Puratattva: Bulletin of the Indian Archeological Society 39.