Critically informed writing about comics, an endeavour with a long but often marginal history in the scholarly world, has flourished over the past two decades as never before. The rise of comic book studies is connected to the increased status and awareness of comics as an expressive medium and as part of historical records.

The notion that comic books are unworthy of serious investigation has given way to a widening curiosity about them as artefacts, commodities, codes and pedagogical tools. They are no longer synonymous with banality, and have captured the interest of a growing number of scholars working in the field of historically oriented social sciences. Comic books are an integral component of contemporary media culture, and extending their studies into a new and fascinating realm of non-Western popular culture certainly seems timely.

As an object, comic books have been defined by several scholars. David Kunzle’s definition is most suited to the idea of comic books in India. Kunzle says that a comic book must have a sequence of separate images that tell a story which is both moral and topical. According to him, the medium has to be more visual than textual, and it must be possible to be produced on a mass level.[1]

The forerunners and prototypes of comic books existed in India in the form of cartoons and strips that were found in Delhi Sketch Book and Awadh Punch, which started publication in 1850 and 1877, respectively. But the history of Hindi comic books, according to Kunzle’s definition, can be traced back to 1964, when Indrajal Comics, an offshoot of Times Group, published the first ever Hindi comic book titled Vetal ki Mekhla (The Phantom’s Belt). The first 32 issues contained stories of American cartoonist Lee Falk’s character Phantom, but after that Indrajal also started to publish characters such as Falk’s Mandrake, and superheroes designed by other American cartoonists such as Alex Raymond’s Flash Gordon, Rip Kirby and Phil Corrigan, Roy Crane’s Buz Sawyer, Allen Saunders’s Mike Nomad and Kerry Drake, and Steve Dowling’s Garth. The translation of these American comic books into Hindi made them more accessible to a large section of young readers in India.

The Phantom quickly became one of the most popular comic book superheroes in the subcontinent. (Fig. 1) He was renamed Vetal or Chalta Firta Pret (the phantom who walks) to suit the Hindi readership. The popularity of Vetal among Indian readers owed to the freshness of his adventures, fluidity of his character and the places in which he operated. Cultural theorist Raminder Kaur and social scientist Saif Eqbal argue that Phantom may have been a mascot of colonialism, a white man located in dark lands, but Indianised as Vetal, thus his adventures became relevant and engrossing.[2] Vetal is a forest guardian who looks after tribal groups and the wildlife. He fights against the poachers, and the industrial and mining corporations that want to exploit the rich bounty of the forest. Hindi journalist Dinesh Shrinet says that Vetal represents a strong critique of modern civilisation, which is marked by various forms of social and structural depravities.[3] Phantom operated in the mythical land of Bengalla, and the name of his father’s killer was Rama. Since Phantom was translated into Hindi, the editors of Indrajal made some minor changes to these names to avoid confusion among Indian readers and controversies because of phonetically Indian names. Bengalla became Denkali and Rama became Ramalu.

Amar Chitra Katha: Shift towards ‘Indigenous’ Comic Books

A major break in the publication of Hindi comic books came in 1967 when India Book House started the Amar Chitra Katha series helmed by Anant Pai. Trained as a chemical engineer, Pai joined the publishing industry in the 1960s, and was employed by the publication division of the Times of India. It is said that once Pai watched a quiz contest on Doordarshan where children could answer questions on Greek mythology but did not know the name of Rama’s mother.[4] His nieces and nephews also showed him stories they had written that had characters with English names. Pai found this alienation from Indian cultural roots disturbing. He conducted an experiment in a Delhi school to establish that the comic format works well as a mode of communication for young minds. He then conceived the idea of an indigenous comic book for children that would have the stamp of approval from parents and teachers since they would provide information on Indian mythologies and histories. He pitched the concept to Times Group but without any success. However, India Book House, a publisher based in Bombay, lapped it up. The series was named Amar Chitra Katha (literally, immortal picture stories) or ACK as it is popularly known. Although the first 10 issues of ACK were Western stories like Pinocchio and Cinderella, from the 11th issue onwards, it came into its own and started to publish stories related to Indian mythology.

Along with illustrator Ram Waeerkar, Pai produced the first issue of Krishna in 1969. It was followed by stories such as Shakuntala, The Pandava Princes, and various others. ACK sold just 20,000 copies in the first three years, but, by the late 1970s, it was selling 50 lakh copies a year and had a peak circulation of about 7 lakh a month. India Book House started to bring out at least one comic book a month by 1975, and sometimes as many as three. While Pai initially wrote the first few stories himself, he soon hired a core team of writers and editors, which included Subba Rao, Luis Fernandes and Kamala Chandrakant, who were responsible for the attempt at authenticity and balanced portrayal of history in comic books that became the hallmark of ACK.[5]

ACK comic books mostly retell stories surrounding Puranic heroes and historical characters. These iconic figures vary from the founders of the Maurya and the Gupta dynasties and from the period of the Mughals in India (including Babur, Akbar and the Rajput king Rana Pratap) to political visionaries, leaders and royal warriors who took part in the struggle for independence during the British rule (such as Rani Laxmibai, V.D. Savarkar and Mahatma Gandhi). Apart from these political and religious biographies, ACK also retells fictional and dramatic works from literary texts such as Abhijanshakuntalam and Mrichhakatikam, and folktales from various corners of the country. Visual culture researcher Aryak Guha says that ACK and its storytelling imposed standards of a fictive Indian identity in the service of the nation state which was largely ‘Hinduised’ and gendered. The representation and interpretation of history fed directly into civic ideals of good behaviour and citizenship.[6]

Several scholars such as Nandini Chandra and Aruna Rao have criticised ACK because of the way they portray Muslims and women.[7] Critics have also spoken against its projection of brahmanical and upper-caste Hindu culture as superior to other viewpoints, and its uncritical presentation of Indian caste hierarchies.

The success of ACK can be attributed to clever marketing strategies and the publicity that Anant Pai managed to generate. The marketing was directed towards urban centres, where Pai had an enormous following among children as ‘Uncle Pai’. Cultural critic Nandini Chandra says that the ACK authors deployed the individual biography form of storytelling as they collected stories from various ancient sources.[8] Thus, the storyboard form in which ACK adapted the various tales, legends and dramas played upon great individuals as role models. The individual biography was also useful to address a primarily English-speaking upper-caste, middle-class child audience, for whom the bourgeois individual was the standard. Pai’s efforts to blend the medium of comic books with an effective pedagogical tool was evident in events such as the much publicised ‘The Role of Chitra Katha in School Education’ seminar held in New Delhi in 1978.

Bela-Bahadur, Chacha Chaudhury: The Way Forward

In 1976, Indrajal published its first indigenous series, based on the action-adventure hero Bahadur. Bahadur was the brainchild of cartoonist and artist Abid Surti, who was famous for creating the cartoon character Dhabbuji. Bahadur was a vigilante without a secret identity. (Fig. 2) He had one foot in modernity and the other in rural roots. Aruna Rao says that Bahadur’s appearance represented the Indian appropriation of Westernisation into traditionalism.[9] Bahadur was tall and mustachioed and wore blue jeans with a saffron kurta. Surti said that the blue jeans indicated Bahadur’s Western-style modernity, while the kurta showed his affiliation to his Indian roots.[10] One of the most important aspects of this series was the presence of Bela, Bahadur’s live-in girlfriend who gradually became an equal partner in his adventures. It was a risque experiment by Bahadur’s creators which paid off. Amar Chitra Katha and Indrajal Comics were both based in the city of Bombay, and were primarily targeted at an audience that was mostly urban. These two publishing houses had firmly established a comic book culture in the Hindi public sphere by the 1970s. Inspired by their immense popularity, a number of other publishers jumped into the business. A major trend was clearly discernible. There was a shift from Bombay as the hub of comic book publication, and the business moved to Delhi and Meerut, where the Hindi pulp industry had been booming since the 1950s and 1960s. In 1978, Gulshan Rai established Diamond Comics. The most popular characters in Diamond Comics, such as Chacha Chaudhary, Billoo, Pinki, Raman and Shrimatiji, were created by the cartoonist Pran Kumar Sharma. These characters mostly functioned within the urban middle-class families and neighbourhoods.

Chacha Chaudhary, the most popular Diamond Comics character, made his first appearance in the picture magazine Lotpot. Pran showed him as an elderly rural man with a clear peasant origin. The cartoonist later switched over to Diamond Comics and released the character of Chacha Chaudhary in a comic book in 1981. This change of ownership led to Chacha being transformed into a respectable urban man whose role was to teach traditional cultural and moral values to the younger generation. Kaur and Eqbal argue that the movement of the character from village to town was parallel to urbanising trends in India along with increase in migration from rural sectors, and Chacha Chaudhary and his sidekick Sabu (a 15-foot giant from the planet Jupiter) took on the moral dilemmas and criminal dangers of urban settings.[11] Apart from such characters drawn from everyday life, the Diamond Comics universe also had characters that dabbled in magic, such as Tauji and Chacha–Bhatija. Fauladi Singh, another popular character, was primarily a science-fiction figure engaged in fighting futuristic alien invasions rather than dealing with crimes afflicting the contemporary world.

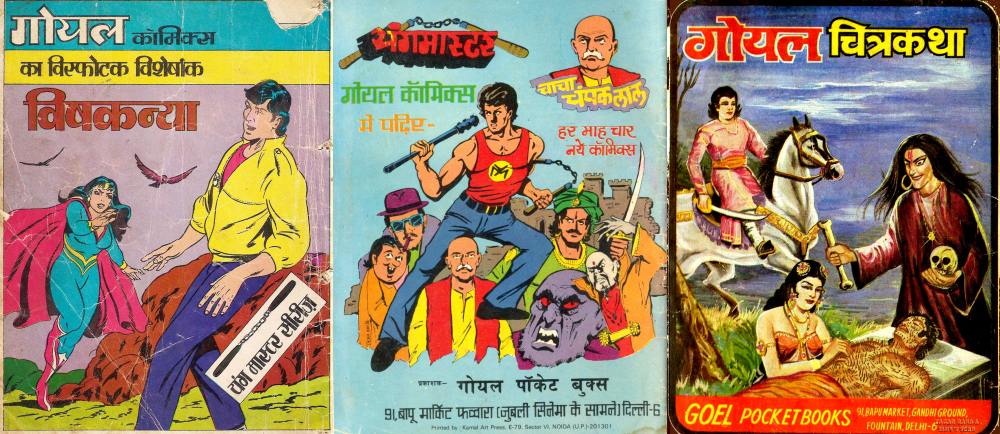

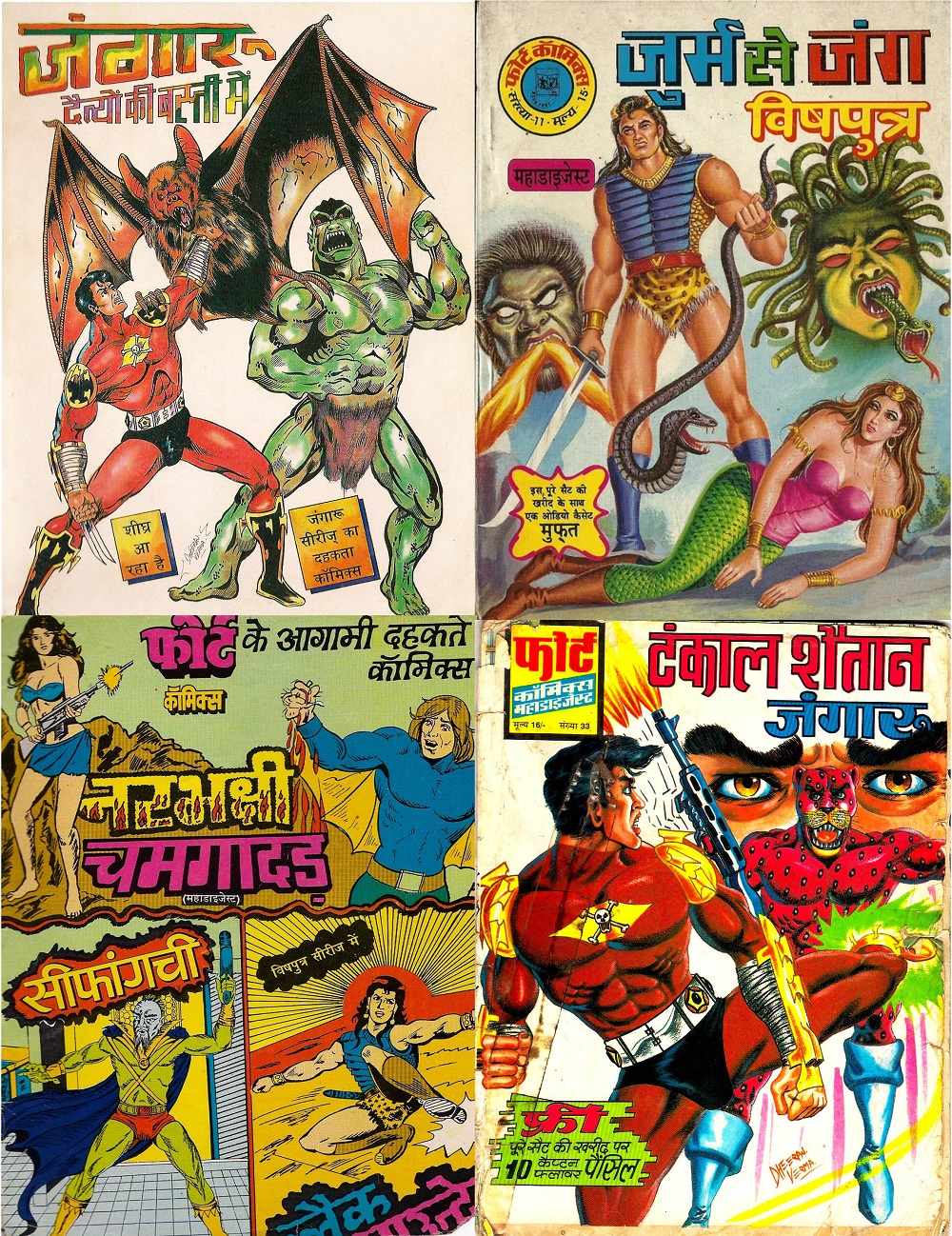

Manoj Comics was another major publisher to come out of Delhi. It was a major competitor of Diamond Comics and Raj Comics. Ram–Rahim were the most popular characters to appear in Manoj Comics. Ram and Rahim were two young boys who were primarily secret agents. In most of the stories their job was to save the world from wicked scientists or enemies of the nation; they also ventured into the realm of the mythical and the supernatural. The choice of the characters’ names as Ram and Rahim was indicative of religious harmony. It is generally accepted among the reader community that Ram–Rahim’s Dracula series was one the best and most popular comic book series to appear in Hindi. Sagar Salim, Crookbond, Hawaldar Bahadur and Mahabali Shera were other popular characters from Manoj Comics. The market was soon flooded with a number of comic book houses such as Nutan Comics, Radha Comics, Goel Comics, Chunnu Comics, Ganga Chitrakatha, Chitra Bharti Kathamala, Tulsi Comics, Fort Comics, etc. (Figs 3, 4 and 5)

Raj Comics: The Game Changer

Established by Rajkumar Gupta and his son Sanjay Gupta in 1986, the arrival of Raj Comics on the scene was a landmark event as the publisher soon became the market leader. Kaur and Eqbal identify five different types of comic books that overlapped with each other and formed the majority of Raj Comics’ output.[12] First, the mythological and medieval fantasies that focused on swords, sorcery and folklore. These were stories based on simple themes such as demons (Paropkari Rakshasha or The Do-Good Demon, circa 1989), village residents (Baat ka Dhani or A Man of his Words, 1987), magicians (Jadugar ka Qila or The Fort of the Magician, 1990), kings (Pagal Raja or The Crazy King, 1986), queens (Raaj Pratigya or The Royal Vow, 1990), princesses (Kanakpur ki Rajkumari or The Princess of Kanakpur, 1985), and newly created fantasy heroes that were located primarily in a mythical rather than a modern era (characters such as Tilismdev, Gojo and Ashwaraj). Second, comedies, prominent among which were the satirical characters of Bankelal and Gamraj. According to Kaur and Eqbal, Bankelal was at extreme odds with virtually everything and as a result demonstrated a playful postmodern turn.[13] Third, detective fiction and other contemporary stories, such as stories concerned with criminal cases or with a social or moral message. For instance, Do Bechare (The Poor Duo, circa 1986) highlighted the ordeals of two brothers who were afflicted with night blindness (a common ailment in rural India due to the deficiency of Vitamin A), and Thugon ki Nani (Grandmother of Thugs, 1984) narrated the ingenuity of a rural housewife who countered a gang of thugs. Fourth were the supernatural horror stories that emerged most strikingly in the ‘Thrill Horror Suspense’ series from 1986–87. Fifth, and most significant, were the superhero books that became the hallmark of Raj Comics, where the protagonists wielded certain superpowers, much like the Western superheroes.[14]

Apart from Super Commando Dhruv, the most popular Raj Comics superhero was Nagraj. According to Sanjay Gupta, one of the concept creators of Nagraj, the main inspiration behind this superhero was Spider-Man. Spider-Man made his first appearance on Indian television sometime in the early 1980s as a cartoon serial and became quite popular.[15] Gupta saw it and was inspired to create an Indian counterpart. Suchitra Mathur says that the influence of Spider-Man on Nagraj was obvious.[16] It started with the animal motif that was most clearly visualised in the costume and background story that traced the origins of both the superheroes to science labs, and to technical details such as snakes shooting out of Nagraj’s wrists in imitation of Spider-Man’s web-shooting wrists. As with Spider-Man’s webs, these snakes became the chief source of Nagraj’s powers, including the all-important ability to ‘fly’ by swinging on snake ropes. Even the ethical framework of the origin story, which governs the superhero’s role and purpose in society, was similar. Spider-Man’s transformatory experience of Uncle Ben’s murder was echoed in Nagraj’s encounter with Baba Gorakhnath, a guru figure who guided Nagraj towards using his powers for the good of the society.[17] Mathur says that as a superhero Nagraj travelled either within the local (fictional spaces like Mahanagar or Nagdweep) or the global (from Africa and the Middle East to America), and in the process conspicuously skipped over the national.[18] She adds that this may be seen as a way to make Nagraj an embodiment of the ‘glocal’, a third space that is relatively autonomous to the hegemony of both corporate globalisation and militant nationalism. And it is this possibility that made Nagraj much more than just an Indianised American superhero; it made him symptomatic of vernacular popular culture as a precariously poised space for the articulation of alternate identities and discourses of empowerment. The popularity of Nagraj can be gauged from the fact that the year 1997 witnessed two major litigation cases surrounding comic books: Raja Pocket Books vs Radha Pocket Books and Goel Pocket Books vs Raja Pocket Books. Nagesh by Radha Comics and Nagputra by Goel Comics had very similar storylines to Raj Comics’ Nagraj, to the point that Raj Comics took the two to court and won on grounds of plagiarism. These were among the first litigation cases in the history of comic book publications in India, and demonstrated that the Indian comic business was getting very serious.

The popularity of comic books also led to the boom in the renting library culture across north India. In almost all the mohallas of every town there were small libraries that provided comic books on rent to the readers, usually at 10 per cent of the MRP. The renting library business became quite profitable as for the majority of Indian middle-class readers this was the only way they could afford to read comic books. Most of these libraries were run by comic book aficionados, who wanted to profit from their own collection. Kaur and Eqbal argue that children from the mofussil middle classes were the most pervasive readers of these vernacular comics published from Meerut and Delhi.[19] They were mainly from low- to middle-income backgrounds whose families had enough to invest in their education and did not have to send them for labour. Some children might even have had a small amount of pocket money. Readers also included children of small shop and business owners and managers, petty agricultural landlords and people employed in the public sector and private–public enterprises such as Indian Railways and Coal India Limited. So, it is clear that the Hindi comic books found favour across a broad range of readership.[20]

Notes

[1] Kunzle, The Early Comic Strip, 2.

[3] Shrinet, ‘शहरी सभ्यता का आलोचक वेताल.’

[4] Daftuar, ‘Goodbye, Uncle Pai.’

[5] Rao, ‘From Self-Knowledge to Superheroes,’ 39.

[6] Guha, ‘Past-Perfect,’ 117.

[7] Rao, ‘From Self-Knowledge to Superheroes.’

[8] Chandra, ‘The Amar Chitra Katha Shakuntala,’ 1.

[9] Rao, ‘From Self-Knowledge to Superheroes,’ 37.

[10] ibid.

[11] Kaur and Eqbal, Adventure Comics and Youth Cultures in India, 25.

[12] ibid., 87.

[13] ibid.

[14] ibid., 86.

[15] Mathur, ‘From Capes to Snakes,’ 178.

[16] ibid.

[17] ibid.

[18] ibid, 185.

[19] Kaur and Eqbal, Adventure Comics and Youth Cultures in India, 9.

[20] ibid.

Bibliography

Chandra, Nandini. ‘The Amar Chitra Katha Shakuntala: Pin-Up or Role Model?’ South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, no. 4 (2010). Accessed August 8, 2019. http://journals.openedition.org/samaj/3050.

Daftuar, Swati. ‘Goodbye, Uncle Pai.’ The Hindu ‘Young World’, March 7, 2011. Accessed August 8, 2019. https://www.thehindu.com/features/kids/Goodbye-Uncle-Pai/article14938068.ece.

Guha, Aryak. ‘Past-Perfect: Rediscovering “India” in Comics.’ Journal of the Moving Image, no. 11 (December 2012): 116–33. Accessed August 8, 2019. http://jmionline.org/article/past_perfect_rediscovering_india_in_comics.

Kaur, Raminder, and Saif Eqbal. Adventure Comics and Youth Cultures in India. New Delhi: Routledge India, 2019.

Kunzle, David. The Early Comic Strip: Narrative Strips and Picture Stories in the European Broadsheet from c. 1450 to 1825. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973.

Mathur, Suchitra. ‘From Capes to Snakes: The Indianization of American Superhero.’ In Comics as a Nexus of Cultures: Essays on the Interplay of Media, Disciplines, and International Perspectives, edited by Mark Berninger et al., 175–86. Jefferson, North Carolina and London: McFarland and Co., 2010.

Rao, Aruna. ‘From Self-Knowledge to Superheroes: The Story of Indian Comics.’ In Illustrating Asia: Comics, Humor Magazines, and Picture Books, edited by John A. Lent, 37–63. Hawai’i: University of Hawai’i Press, 2001.

Shrinet, Dinesh. ‘शहरी सभ्यता का आलोचक वेताल.’ Comic World. May 6, 2012. Accessed August 8, 2019. http://comic-guy.blogspot.com/2012/05/blog-post.html.