Introduction

Bonbibi-r Palagaan is a dramatic performance tradition connected with the worship of the cult goddess Bonbibi. In contrast to the Bengali literary canon, this popular performance-ritual, which is exclusively practised in the Sundarbans in lower delta region West Bengal (India) and Bangladesh, has survived orally or through handwritten manuscripts in the periphery without receiving much recognition. The word ‘pala’ means a ‘long narrative verse’ and ‘gaan’ means ‘song’ in Bengali. Traditionally, Bonbibi-r Palagaan was simply recited or sung as a eulogy to the deity to invoke her blessings. It later evolved as an enactment form, where the various exploits of Bonbibi in Bhati-r Desh (the land of tides, i.e., the Sundarbans) are acted out. The fact that this performance-ritual is practised even today suggests the continuity of this tradition of worship. Bonbibi-r Palagaan is considered to be the representative performance-ritual of the Sundarbans and also an emblem of the syncretist nature of the region.

The Sundarbans is an archipelago situated in the southernmost part of the Gangetic basin and extends between two rivers—river Hoogly in the west, in West Bengal, India, and river Meghna in the east, in Bangladesh. The word ‘Sundarbans’, which literally means ‘beautiful forest’ (‘sundar’ means beautiful, ‘ban’ means forest), is used to denote both the forest and the region. The word ‘sundar’ also comes from the Sundari (Heritiera fomes) tree growing in the mangrove forests of Sundarbans. The entire region spans 25,500 sq. km, two-thirds of which lie in Bangladesh and the rest in India.

The Sundarbans in India spans two districts in West Bengal—North and South 24 Parganas—covering 19 blocks and an area of 9,630 sq km, of which almost half is forested. The Sundarbans is the largest natural habitat of royal Bengal tigers, and it is home to nearly 271 tigers in India alone (Mukhopadhyay). Out of the 102 islands in the Indian Sundarbans, about 54 are inhabited and the rest are notified as reserve forests. What is less known is that the region is also the abode of about 4.44 million people (Ghosh et al. 2015). Located on the coastline, the landscape is crisscrossed by rivers and streams, is prone to cyclones, and houses one of the largest tracts of estuarine forest in the world; this makes the residents vulnerable to calamities of various kinds.

In a landscape such as this, Bonbibi becomes a focal point for faith and absolute devotion. The residents, who depend on the forest for their daily survival, by fetching wood, honey, wax, fish, and crabs from the Sundarbans, are the primary worshippers of Bonbibi. The word ‘ban’ in Bengali means ‘forest’, while ‘bibi’ originates from the Persian word for lady or wife; the word ‘Bonbibi’ thus literally means the ‘lady of the forest’. Bonbibi is an Islamic deity, almost an oxymoron according to our present normative understanding, and is believed to have travelled on Allah’s orders from Medina to the Sundarbans to protect the distressed residents as well as the animals of the forest. Bonbibi is one of the syncretist cults of Bengal, and both Hindus and Muslims of the region pray to the deity.

The lore of Bonbibi, like any other oral literature, has changed forms and contours, still exists in a flexible state in the present society and appears destined to transform further. The myth of Bonbibi-r Palagaan is built on an intricate system of myths which trace their origin to important socio-political changes in the history of Bengal—the rise of Islam around the 13th century followed by the liberal spirit of Sufism in rural lower Bengal in the 15th century and thereafter developing Hindu-Muslim syncretism in the medieval period.

Bonbibi: A Living Tradition

The jongol (forest) with its looming presence is an unavoidable element in the lives of the people of the region. The Sundarbans is comparable to the sea as depicted in J.M. Synge’s play, Riders to the Sea. It is like a maze that the residents cannot resist, and thus they constantly get caught in it. The islanders depend on the forest for their daily survival—for fetching wood, honey, wax, fish, and crabs and they often encounter danger and deaths in various forms. This intertwining of fear and faith has led to the worship of nature, embodied in the form of the cult goddess Bonbibi, the guardian of the forest. Though the residents depend on the forest for their survival, yet forest workers loosing lives is a regular phenomenon. This perpetual war/dependence dynamic translates into worship and performance. Bonbibi-r Palagaan thus exhibits a struggle for survival. An integral part of the puja, the performance, is seen as a way to mitigate the wrath of natural forces. Certain sacred rituals are practised during the performance, such as the body of the actors are to be kept clean, actors are barred from eating non-vegetarian food, woman actors do not take part while menstruating etc. Such rituals are faithfully followed so as to maintain the sanctity of worship.

Tracing the History

[Islam] has changed its colour, if not its formal official creed, in the various countries and climes; Islām of Maghrib in Sudan has its own changes, as has Islām of Mashriq in Persia, Jāvā and Mālaya. But nowhere was it so amazingly changed with respect to special aspects as it did in India as well as in Bengal (Haq 1975:317).

Enamul Haq, in his seminal work, A History of Sufi-ism in Bengal, writes that during the 16th and 17th centuries, 'Sufism in Bengal, along with the Sufism in India, was in a metamorphic stage, after which it took almost independent form with a mixture of local as well as extra-territorial thoughts' (Haq 1975:2). According to Haq, this period of Sufism in Bengal (also called the Middle Period of Sufism in Bengal), saw the creation of a tremendous base for Sufism in Bengal, specifically in rural Bengal. If Islam became popular in India under the guise of Sufism, then the main agents who propagated the religion were Sufi saints, popularly called pirs. The Sufi pirs imbibed many practices that were local and non-Islamic. With a highly stratified and oppressive Hindu society on the one hand, and the decadence of Buddhism on the other, Bengal proved to be fertile ground for the new religion. Though the initial aim was to expand Islam’s base in India, what evolved in rural Bengal was a metamorphosis of Islam, which Enamul Haq calls ‘popular Islam’. Many pirs and piranis emerged as cult figures, and they were acknowledged in various regions as demi-gods. Gazi Miyan, Panch Pir, Pir Badar and Khaja Khizir were worshipped in a Hindu-ised way. Satya Pir, Manik Pir, Pir Gorachand, Barkhan Gaji, Bonbibi, Ola Bibi, Darbar Bibi, and many more began to be worshipped as local cults formby both Hindus and Muslims.

The Middle Period of Sufism in Bengal also saw the fusion of Bengali Hindu traditional literary genres with Perso-Arabic Islamic literary genres. Traditional Hindu literary categories such as mangalkabyas[1] influenced the development of Perso-Arabic kissa or keccha[2] literature in the native land in the native language; this led to the evolution of a distinct kind of literature called Pir Sahitya—Bengali literature concerning the lives of pirs or piranis. The language used in Pir Sahitya was called Musalmani Bangla[3] or Islami Bangla. Narratives of pirs like Satya Pir, Kalu Gaji, Barkhan Gaji, Manik Pir, Machlandi Pir, Ismail Gaji, Jafar Khan Gaji, Pir Gorachand, Mobarak Gaji, Ekdil Shah, and many more still circulate in rural Bengal. Satya Pir-er Panchali by Faizulla (16th to 17th century) and Manik Pir-er Panchali by Fakir Muhammad (18th century) are two such examples.

Johuranama is a kissa written in the panchali[4] form. Written in Musalmani Bangala, this Pir Sahitya work narrates the endeavours of Bonbibi in the Bhati-r Desh. Johuranama consists of three texts

(i) Bonbibi Jahuranama 1284 (1877–78 CE) by Boinuddin

(ii) Bonbibi Jahura Nama 1287 (1881 CE) by Munshi Mohammad Khater

(iii) Bonbibir Jahuranama 1305 (1899 CE) by Mohammad Munshi.[5]

These texts are part of the early print culture of Bengal; in specific, they form a part of Battala[6] literature.

The plot of Bonbibi-r Palagaan can thus be traced to either the written punthis of Johuranama or to the oral, folk stories of the land. It is difficult to confirm whether the performative text of the Palagaan precedes the printed Johuranamas or vice versa. The story of Bonbibi has been re-written and re-created by numerous Palagaan directors or script writers called palakaars. The script of Bonbibi-r Palagaan has thus been recorded in numerous unpublished, handwritten manuscripts that the palakaars had developed based on the demands of the production at the time. One such pala script has been published in Sujit Kumar Mandal’s book, Bonbibir Pala.

The Performance of Bonbibi-r Palagaan

Palagaan is an old performative form that involves the reciting and singing of long narrative oral verses accompanied by mimetic gestures. The origins of Palagaan go back to the 10th century CE with Gītagovinda[7] by Jayadeva and Śrīkŗşņakīrtana[8] by Baḍu Caņḍidāsa. It is an important element in Hindu ritual performances and involves the dramatisation of myths and stories about gods and goddesses. This artistic practice narrativises and enacts the exploits of gods and goddesses. Palagaan thus is traditionally associated with Hindu religious practices.

Earlier it has been mentioned that popular religious literary genres like panchali or mangalkaabya were appropriated by Muslim poets to create a new genre called Pir Sahitya, a similar appropriation can also be noticed in the sphere of performitivity. The narrative of Bonbibi, as presented in Johuranamas, borrows from the already existing Palagaan performative form of Palagaan to fashion the ritual performance, Bonbibi-r Palagaan.

According to Sashankhasekhar Das’s Bonbibi, Basiruddin Gayen of the village Bhomra, Satkhira district, Khulna division (now in Bangladesh) first scripted and performed the play Bonbibi-r Jatra in Bhurkhunda (now in North 24 Parganas, West Bengal) in the Bhabanipur zamindar in the estate of a British company in 1942. Girindranath Das in Banglar Pir Sahityar Katha states that Bonbibi scripts were written and performed between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century. Satishchandra Choudhury’s Bonbibi, the Palagaan performance, was produced in 1909 (Das 2004:17). However, it is impossible to pin down the date of the earliest performance of Bonbibi-r Palagaan, which is suggestive of its folk nature—it cannot be traced back to one original performance. None of these dates can be authenticated because of the lack of published scripts. Sashankhasekhar Das’s claim that the first Palagaan performance was held in 1942 thus becomes invalid since it has been established that Palagaan was performed much before that.

Bonbibi-r Palagaan, like any folk performance form, has altered in nature over the course of time. Bonbibi-r Palagaan has now developed into two forms—traditional Bonbibi-r Palagaan and contemporary Bonbibi-r Palagaan. Traditional Bonbibi-r Palagaan can be further categorised into two kinds representations: Ekani Pala and Bonbibi-r Palagaan. The word ‘ekani’ comes from the word ‘ek’, which means ‘one’. Ekani Pala is a solo performance by one artist who sings, narrates the story, and also acts out certain parts of the narrative. The main singer is called gayen, and is usually accompanied by a dohar or an accompanist. The dohar plays music and occasionally engages in dialogue with the gayen during the performance.

The traditional Bonbibi-r Palagaan form follows the traditional Palagaan form, where the dohar and gayen sing and narrate the story. Songs play an important role in the development of the plot. The Palagaan script is largely fluid and allows room for improvisation which enables the performer to make spontaneous additions into the texts. It is not divided into Aristotelian acts and scenes and is a form of ritual performance. The amateur actors are primarily forest workers who perform the Palagaan so as to pay tribute to the deity.

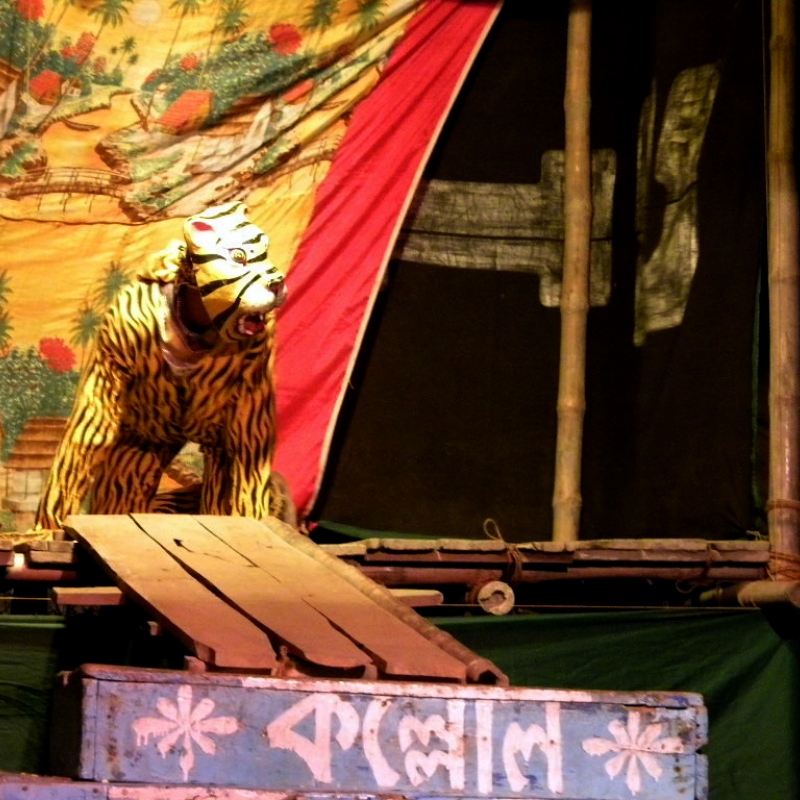

The contemporary Palagaan form incorporates elements from contemporary Jatra (popular folk theatre of Bengal), which in turn was influenced by 19th–century European theatre. Contemporary Bonbibi-r Palagaan is no longer solely ritualistic, performed to worship Bonbibi. Professional actors and not amateur forest workers perform contemporary Bonbibi-r Jatra Palagaan. It is produced as a mode of entertainment for the residents of the Sundarbans. It has thus imbibed a lot of the features of urban Chitpur Jatra performances that are held on a structure like a proscenium stage. The plot is also divided into acts and scenes. Popular characters from Jatra shows such as Bibek, Biswakarma, Ghanturam and Jhanturam have been incorporated into the script to make the show more popular amongst its audiences. Thus the contemporary Bonbibi-r Palagaan is also referred to as Bonbibi-r Jatrapala or Dukhey Jatrapala.

Composition of Bonbibi-r Palagaan

Bonbibi-r Palagaan goes beyond the narrative mentioned in Johuranama and draws its material from local myths. The narrative of the story can be partitioned into three:

- Janmakhanda[9] or Bonbibi’s birth in the tidal land

- Narayani-r Jang[10] or battle with Narayani

- Dukhey Jatra[11] or the travails of Dukhey

Below are outlines of these three sections of the plot.

Janmakhanda

Fakir Ibrahim and his wife Phulbibi used to live in Medina. They were childless and decided to pray to Rasul[12] for a son. Rasul informed them that no child would be born to Phulbibi, but if Ibrahim were to be married again, he would have twin children. Phulbibi consented to Ibrahim’s second marriage, on condition that he grant her a karaar (promise), which she could demand when necessary. Without suspecting her wicked intentions, Ibrahim readily agreed to it and married Gulal, the daughter of Fakir Shah Jalil of Mecca.

Meanwhile, Allah commanded Bonbibi and Shah Jangali, who had then been residing in beheste (heaven), to be born on earth from the womb of Gulal, so that they can accomplish a divine mission. They were sent to Atharo Bhati-r desh (land of 18 low tides, i.e., the Sundarbans) to protect the land from the ‘Hindu’ deity, the half-Brahmin sage, half-tiger Dakkhin Rai. When Gulal’s nine months of pregnancy was over, Phulbibi evoked her promise and demanded that Gulal be exiled to the forest. Ibrahim, trapped by his own vow, pledged to deceive Gulal with a disconsolate heart. Ibrahim led Gulal into the forest and left her there when she fell asleep. When she woke up, Gulal looked for her husband, but could not find him. She cried her heart out only to realize that her husband had left her in a desolate and dangerous forest all alone. Eventually, Gulal gave birth to twin children—Bonbibi and Shah Jangali—in the forest; and these children were none other than the messengers of Allah.

Without any access to food in the forest, Gulal became tired and hungry. She left her daughter and took her son with her. Allah sent a deer who breast-fed little Bonbibi and took care of her. Shah Jangali, on the other hand, was growing up under the protection of Gulal. After seven years, Ibrahim, overcome by guilt, returned to the forest in search of Gulal. Ibrahim found Gulal and Shah Jangali in the forest and offered to take them back home. Immediately, Bonbibi reminded Shah Jangali of their divine purpose and why they had been born in the forest. Together, Shah Jangali and his sister set out to seek their final orders from the rasul in Medina. After receiving khilafat (heirship) from the rasul they headed back to Hindustan. After crossing the Ganga, they reached the east of India and finally arrived at Baadaban[13].

Narayani-r Jang

Bonbibi and Shah Jangali commenced their pursuit with azan[14] in Baadaban. Azan became a call of warning to the earlier residents of the forest. The land was the realm of Dakkhin Rai and his mother Narayani. They were the Hindu god and goddess ruling over this region. Narayani first fought Bonbibi, claiming that only a woman should fight a woman. In the fight, Narayani was vanquished. Narayani accepted Bonbibi’s supremacy and offered her entire ascendancy to Bonbibi. But Bonbibi declared that she had no intention of disheartening her and offered to call Narayani her ‘shoyi’ (friend). She proposed to form a union and rule the land together.

Dukhey Jatra

In another locale in Barijhati village, there lived a poor shepherd called Dukhey with his widowed mother Bibijaan. They eked out their livelihood by working in other households. Dhana, a honey collector and a trader, approached Dukhey and offered him work. He tempted Dukhey by offering to teach him the trade and also promised to get him married. Owing to their extreme poverty, Dukhey readily agreed to work for him. Dukhey’s mother was unhappy about this decision for she thought the forest was dangerous and would put Dukhey unnecessarily at risk. But seeing that Dukhey was so steadfast in his decision to go to the forest and collect honey, she informed him about Bonbibi and instructed him to seek her help if he ever were in danger in the forest.

Dukhey and Dhana, along with other sailors, set sail towards the forest. After crossing Barunhati, Santoshpur, Kanaikathi, and Herobhanga, and the rivers Raimangal and Matla, they finally reached the jangal (forest). Astonishingly enough, they could not find a single drop of honey in the forest since the bee hives were completely empty. The Hindu god, Dakkhin Rai, had tricked them since they had entered the forest without offering worship. Dakkhin Rai told Dhana that he would find honey in the forest only if he sacrificed Dukhey to him. If Dhana chose to disobey him, all the sailors and he himself would be killed by Dakkhin Rai’s adherents, i.e., the tigers in the forest and the crocodiles in water. Dhana was instructed to go to Kendokhali where they would get ample amount of honey which could fill seven boats. In return, Dhana had to leave Dukhey as revenue. Dhana was thus left with no choice.

Dukhey heard the entire conversation between Rai and Dhana. Frightened, Dukhey remembered what his mother had told him. He started praying to Bonbibi, and she appeared immediately. After listening to Dukhey, Bonbibi consoled him saying that she would be able to protect him only after he is abandoned in Kendokhali by Dhana. When they reached Kendokhali, all were amazed to see the amount of honey that was available there. Finally, as Rai had instructed him, Dhana convinced the other sailors and they left Dukhey on shore. Dukhey was sent to the forest to fetch wood for fuel and was finally duped. Seeing the boats sail away from the shore, Dukhey kept crying and requested them not to leave him, but in vain.

Dakkhin Rai, in the disguise of tiger, lurked in the forest. Bonbibi appeared in the forest to rescue Dukhey. Shah Jangali and Dakkhin Rai engaged in battle, and finally, Rai was ultimately defeated by Jangali. Dakkhin Rai fled and reached Barha Khan Gaji’s abode. Shah Jangali chased him, and on reaching Gaji’s home, reprimanded him: being a Muslim fakir, how could he give refuge to a beast like Dakkhin Rai? The three of them finally decided to go to Bonbibi for final judgment. Gaji explained to Bonbibi that she should forgive Dakkhin Rai since he was like her son. Surprised, Bonbibi asked him, 'Kemone Dakkhina Rai beta mor hoy?' ('How can Dakkhin Rai be my son?'). Gaji cleverly illustrated that Bonbibi had once called Narayani her ‘shoyi’ (friend). So in that sense, Narayani’s son was Bonbibi’s son too. Unable to refute the argument, Bonbibi accepted Dakkhin Rai as her son and pardoned him. Dakkhin Rai promised to gift Dukhey honey and wax. Barha Khan Gaji assured him seven vessels of wealth. Bonbibi rescued Dukhey and sent him back to his village. Bibijaan had been blinded and grief-stricken at the loss of her son. Bonbibi cured Bibijaan and restored her son to her. Bibijaan and Dukhey were mesmerized by the miracles of Bonbibi. They pledged to go around begging in the village to collect money in the name of Bonbibi and distributed kheer-khairaat (rice pudding) amongst the people and told everyone about the miracles of Bonbibi.

With the wealth that Barha Khan Gaji had promised, Dukhey became prosperous and powerful. Dukhey’s status rose and he became a Chaudhury[15] in the village, with the grace of Bonbibi. When Dukhey wanted to punish Dhana for betraying him, Bonbibi pointed out to him that it was because of Dhana that Dukhey had met Bonbibi and sought her refuge. So he should pardon Dhana and marry his daughter, Champa. Abiding by Bonbibi’s commands, Dukhey married Champa. The tale ends with their marriage ceremony.

Contemporary Interventions

Bonbibi-r Palagaan, being a folk performance, is flexible in its structure and performances and thus changes with time. The mythic oral narratives were scripted, written, and printed in the form of Johuranama. It also changed in genre and took the form of Ekani pala, was elaborated into Bonbibi-r Palagaan, and was later influenced by Bengali Jatra. As discussed earlier the plot as well as the presentation has been influenced by urban contemporary Jatras.

Bonbibi-r Palagaan has further changed and transformed with the advent of tourism in the Sundarbans. In recent times, the government has showcased Bonbibi-r Palagaan in cultural forums across the state and the country. Palagaan artists from the Sundarbans have been invited to perform in many government-sponsored forums so as to make the form more prominent. Today Bonbibi-r Palagaan has been recognized as an important tool to promote tourism to the Sundarbans. Tourism in return has influenced the way the Palagaan is presented and performed. For instance, Bonbibir Palagaan is now included within the tour itineraries for the tourists. The overnight performance is now compressed into one or two hours and only a few episodes are performed for the tourists. Thus, the performance which had earlier served as a ritual to worship the deity has metamorphosed into being an important source of entertainment as a result of tourism. The most interesting fact of the performance is that the traditional ritualistic Bonbibi-r Palagaan and the contemporary Bonbibi-r Jatrapala or shorter pala for tourists all exist simultaneously. This is suggestive of the protean nature of Bonbibi-r Palagaan, which has survived colonial times, carries within its narrative structure the Marichjhapi massacre[16] and Aila disaster[17] and continues to be pregnant with thoughts of the past and present times.

[1] Mangalakaabya is the 'genre of premodern Bengali literature, a genre that typically glorified a particular deity and promised the deity’s followers bountiful auspiciousness in return for their devotion' (Eaton 1994:216). Manasamangala, Chandimangala, and Dharmamangala are important mangalkaabya texts.

[2] Kissa or keccha are short stories translated from Perso-Arabic romances. Kissa traditional praņayakāvya (love tales) were written in Bengali using many Perso-Arabic words. Nachhiman Bibir Kissa, Alif Laila, etc. emerged as significant genres of the period, which later led to the formation of the Pir Sahitya genre.

[3] Reverend James Long was the first to use the phrase ‘Musalmani Bangla’. It is a distinct kind of language used in Bengali punthi or kissa literature which used Persian and Arabic words mixed with Bangla or Bengali.

[4] Panchali is a class of Bengali long narrative verse poems celebrating the glory of a local deity. It is a folk, oral poetic form recited as rhymes.

[5] Date derived from Girindranath Das (Das 1998:412).

[6] 'Battala a commercial name originating from a giant banyan tree in the Shovabazar and Chitpur area of Calcutta, where the printing and publication industry of Bengal began in the 19th century. Bat-tala is now the name of a police station in Kolkata. The printing and publication industry that developed in and around this banyan tree primarily met the demand of ordinary and semi-literate people. Books were published to serve their taste. Main publications of Bat-tala include puthi, panchali, panjika (calendar), myths and legends etc. Numerous lanes and by-lanes around the banyan tree came to be generally known as bat-tala, and the books published from the place were derogatorily branded as bat-tala literature' (Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh. <http://en.banglapedia.org/index.php?title=Bat-tala>)

[7] Long narrative song, i.e., palagaan eulogizing Govinda, another name for the Hindu god, Śrī Kŗşņa.

[8] Palagaan eulogizing Śrī Kŗşņa.

[9] Janma means birth. Khanda refers to episode.

[10]Jang means fight.

[11] The palagaan episode of Dukhey and his rescue by Banabibi is colloquially called Dukhey Jatra.

[12] An Arabic word meaning ‘messenger’ or ‘apostle of God’.

[13] Badaban: Bada means mangrove. Ban means forest. Badaban refers to the forest of Sundarban which is a Mangrove forest.

[14] Islamic call for prayer.

[15] ‘Chaudhury’ is a titular award that one gains with social upliftment.

[16] Marichjhapi incident: Displacement of refugees who settled in Marichjhapi, an island lying to the northernmost forested part of the Sundarbans.

[17] Cyclone Aila formed in the Bay of Bengal in May, 2009 bringing a massive destruction to both eastern coastal India and Bangladesh.

References

Das, Girindranath. 1998. Banglar Pir Sahityar Katha. Kolkata: Subarnarekha.

Das, Shasankasekhar. 2004. Banabibi. West Bengal: Loksanskriti O Adibasi Sanskriti Kendra.

Eaton, Richard M. 1994. The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier: 1204-1760. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Ghosh, Aditya, Susanne Schmidt, Thomas Fickert and Marcus Nüsser. 2015. 'The Indian Sundarban Mangrove Forests: History, Utilization, Conservation Strategies and Local Perception'. In Diversity 7:149–69. Online at doi: 10.3390/d7020149. (viewed on December 3, 2016).

Haq, Muhammad Enamul. 1975. A History of Sufi-ism in Bengal. Dacca: Asiatic Society at Bangladesh.

Khater, Morhum Munsi Mohammad. 1881. BanaBibi Johura Nama. Kolkata: Gaochiya Library,Mechuabajar.

Mandal, Mousumi. 2011. ‘Banabibi-r Palagaan of the Sundarbans: An Interpretative Analysis’. Unpublished M.Phil. Thesis. Centre of English Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University.

Mandal, Sujit Kumar, ed. 2010. Banabibir Pala. Kolkata: Gangchil.

Mukhopadhyay, Amites. 2009. 'Cyclone Aila and the Sundarbans: An Enquiry into the Disaster and Politics of Aid and Relief'. In CRG Annual Winter Course on Forced Migration. Kolkata: Mahanirban Calcutta Research Group. Online at http://www.mcrg.ac.in/pp26.pdf (viewed on November 21, 2016).

Rahim, Abdul. 1986. Banabibi Johura Nama: Konyar Punthi. Kolkata: Osmania Library.