In the history of Indian vernacular theatre, Hindi language theatre is relatively new. It only evolved with the evolution of modern Hindi prose in the late nineteenth century. This was the period of the ongoing struggle for Indian Independence which was accompanied by a call for social and cultural renaissance. One of the key figures who espoused both these causes and also played a significant role in evolution of modern Hindi literature as well as theatre tradition was Bharatendu Harishchandra. A playwright and an actor, Bharatendu not only added to the body of modern Hindi drama literature but also helped in staging their performances.[1] He translated plays from other languages into Hindi and published reviews of plays in contemporary news magazines and letters.[2] Bharatendu, under his convenorship, established National Theatre in Varanasi; writers belonging to his circle also established theatre groups in Varanasi and Allahabad as well as some cities of Bihar.[3] Thus, the foundation of theatre tradition was laid firmly in the Hindi-speaking belt (comprising mainly of the cities of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar where Hindi is the most widely spoken language) in the late nineteenth century.

Subsequently, there were other efforts to foster Hindi theatre in other cities. One of the most prominent theatre activists involved was Madhava Shukla who founded the Hindi Natya Parishad in Kolkata at the beginning of the twentieth century, which, according to the eminent literary critic Ram Vilas Sharma, ‘maintained and strengthened the bonds between the literary play and the stage’.[4] Some other amateur groups such as Ramlila Natak Mandali of Allahabad and Nagari Natya Kala Pravartan Mandali of Varanasi used to stage plays regularly but only a few writers were associated with them.[5]

However, there was a decline in the tradition of Hindi theatre in post-Independence India. The structural reasons behind this phenomenon were the lack of ‘professional theatre support’ due to which concerted efforts of those writers who were influenced by Bharatendu did not succeed in developing theatre as ‘a force of social importance’[6]. Literary scholar Sisir Kumar Das writes that even with the ‘potentiality of its fantastically large audience,’ the absence of professional stage extinguished any chances of Hindi dramatists staging their plays.[7] As Sharma suggests, Hindi theatre continued to be practised mostly by amateurs with specific reference to organisations like the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA)[8], which had a big role in cementing the foundations of the theatre in smaller cities, especially in northern Hindi-speaking states.

Hindi theatre, throughout its history, has developed within a specific social and political context. Its origins were deeply embedded in the national movement of Independence and the social and cultural renaissance. Both these movements had greatly inspired intellectuals like Bharatendu who laid the foundation of not only modern Hindi theatre but also modern Hindi literature.

Influence of IPTA

Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) started as a ‘low key affiliate of the left wing Anti-Fascist Writers and Artists Association of Calcutta’[9]. With relative success in the early years, its members soon resolved to organise it nationally with branches and chapters throughout India.[10] Founded at the height of national movement for Independence, the Second World War and the Bengal Famine of 1940s, IPTA was focussed on anti-imperialist and anti-fascist agendas.

The aim of the association was to direct its messages to the masses rather than the bourgeoise even though it was primarily composed of intellectuals. Sharma notes that like most theatre efforts after Bharatendu, IPTA too remained amateurish in scope and scale.[11] Performance spaces for IPTA’s plays were more improvised than formal. Their outreach though was extended to many parts of the country, including the Hindi heartland. After Independence, the movement began to disintegrate because of ideological polarisations within IPTA.[12] But its influence sustained in some smaller cities in the form of satellite movements for a few more decades. One of these cities was Agra, where the IPTA’s unit continued to thrive despite its national disintegration.

Origins of Modern Theatre in Agra

IPTA remained relevant in Agra even after the movement declined at the national stage after Independence. Rajendra Raghuvanshi from Agra, who was associated with IPTA since its inception,[13] along with another Agra-based theatre activist and film actor, Bishan Khanna, had established Agra Cultural Squad (ACS) in the city, taking inspiration from the Bengal Cultural Squad, a sociopolitical mobile theatre active during the Bengal Famine. The ACS was in a sense precursor to the Agra IPTA chapter as it later began to function as the local unit of IPTA. Along with IPTA, the children’s unit called Little IPTA and women’s unit called Women’s IPTA were also started in the city during the 1950s.

This momentum, however, witnessed a slowdown, especially during the latter half of the 1960s and through the entire decade of the 70s. It was in 1985, when a national level meeting of IPTA was organised in Agra, that the movement was rejuvenated again. By that time Jitendra Raghuvanshi, son of Rajendra Raghuvanshi, had taken over the reins of the IPTA theatre movement in Agra and continued to nurture local talents until his untimely death in 2012.[14]

Development of Professional Theatre in Agra

One of the organisations that were crucial in not only reviving performance arts but also laying the foundations of professional theatre in the city was Ranglok Sanskritik Sansthan (Ranglok). IPTA, even after 1985, in its second phase in the city, continued to practise theatre amateurishly. The sociopolitical and economic questions had changed but IPTA’s theatre activism was undaunted as they kept raising issues of public importance among the masses. However, the roots of a financially viable and self-sustainable professional theatre grew only in the second decade of the twenty-first century.

Ranglok group attempted to bring professionalism to the theatre in the city by addressing the shortcomings of amateur theatre. Dimpy Mishra, who started learning acting and performance arts in IPTA in the 80s and later pursued theatre studies from Bharatendu Natya Academy in Lucknow, came back to Agra in 2010 after completing his studies and started Ranglok, which was dedicated to nurturing local talent in various aspects of professional theatre.

Performances by Ranglok, unlike the dramas of IPTA which were mostly staged in improvised spaces, are staged in Agra’s multi-seater, government-owned-and-run auditorium, Soorsadan. Consequently, the audiences of the two organisations also differ: while IPTA traditionally excluded bourgeoise and elite from its audience, the Ranglok group aimed to include middle and upper-middle classes as well.

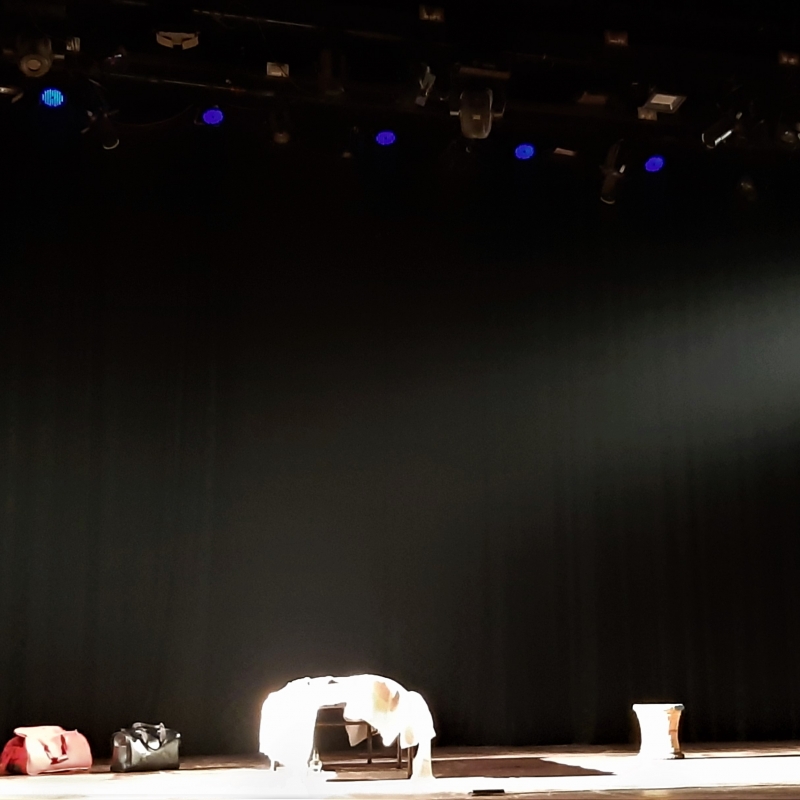

What is common between the two organisations though is the choice of sociopolitical plays, also known as ‘problem plays’ in theatre discourse. Since Mishra started learning theatre with IPTA, his inclination is still towards sociopolitical messaging.[15] In the past decade, the group has staged performances of such plays as Vijay Tendulkar’s Kanyadan (The Gifting of Daughter); Swadesh Deepak’s Court Martial (Fig. 1) and Asgar Wajahat’s Jis Lahore Nahi Vekhya O Janmiya Hi Nahi (One Who Hasn’t Seen Lahore Has Never Been Born) (Fig. 2), as well as adaptations of stories of Pakistani novelist and playwright, Saadat Hasan Manto (Fig. 3); Phanishwarnath Renu’s short story ‘Panchlight’ (Light of the Village Head) (Fig. 4) and stories of Hindi novelist Premchand. These performances have addressed issues of feudalism, superstitions, communalism, casteism, patriarchy, Partition, and other prominent sociopolitical and historical themes.[16]

The most pressing problem that the group faces is that of funding as well as maintaining a steady repertoire of trained actors, many of whom migrate to bigger cities such as Delhi and Mumbai to build their careers in acting after their initial training with the group. Nevertheless, the group has managed to stage about 60 performances of around 30 plays since its registration in 2013. Ranglok has made major advancements, especially in the past three years, in which time not only has it staged about half of its total performances but also organised three theatre festivals (Fig. 5) and multiple independent performances in Agra, in which about 15 plays have been staged by groups from other cities such as Delhi, Mumbai, Patna, Varanasi, Lucknow and Bhopal.

In the past three years, as part of Ranglok’s initiatives, artistes such as Raghubir Yadav, Harsh Chhaya, Lubna Salim, Bakul Thakkar, Amit Behl, Alok Chatterjee, etc., have graced the stage in Agra, providing a taste of professional theatre performances to the audiences in the city. At the same time, veteran theatre directors such as Salim Arif and Ranjit Kapoor have conducted workshops with local artistes. Moreover, the Ranglok group has also performed in various other cities in the past decade, thus putting Agra theatre on the country’s theatre map. Efforts of Dimpy Mishra have also been recognised by the state of Uttar Pradesh, as he was given the Uttar Pradesh Sangeet Natak Akademi Award in 2018 for his contributions to theatre arts in the field of direction. These endeavours have helped build a considerable subscription base of theatre audiences in the city. Around 200 people have become annual paid subscribers of the group in the past three years, and they regularly attend the group’s performances in the city. Regarding the advancements made in Agra for theatre, Salim Arif observes, ‘The materialisation of this facility in Agra is, to me, a big thing. That’s why I would like to invest my energy and time in Agra because a fertile ground is being created here. And a big reason behind it is the local support.’[17]

The history of the Ranglok group shows that the local support of audiences, many of whom also doubled as patrons, has been an important accomplishment. With the training from an organisation like IPTA, Dimpy Mishra has managed to maintain a sociopolitical character of the theatre scene in the city.

Hindi theatre that emerged alongside modern Hindi prose has been able to establish itself in most cities in the Hindi belt with the widespread efforts of organisations like IPTA. For smaller cities such as Agra, local efforts have been important, be it the ACS in the initial days which later metamorphosed into the local IPTA chapter, or the Ranglok theatre group in the present, which is also intimately linked with the IPTA tradition. The sociopolitical theatre trajectory in such cities also stems from this shared heritage of theatre activists.

Notes

[1] Indira Gandhi Rashtriya Mukt Vishwavidyalaya, Hindi Natak aur Ranghmanch, 7.

[2] Ibid, 8.

[3] Ibid, 9.

[4] Sharma, ‘Hindi Drama,’ 91.

[5] Das, A History of Indian Literature, 160.

[6] Ibid, 159.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Sharma, ‘Hindi Drama,’ 94.

[9] Richmond, ‘The Political Role of Theatre in India,’ 323.

[10] Ibid, 324.

[11] Ibid, 323.

[12] Ibid, 326.

[13] Srivastava, ‘Jo Bhi Ho, Humara Swarnakal Toh Yahi Hai,’ 69.

[14] Khandelwal, ‘H1N1 claims Agra theatre personality Jitendra Raghuvanshi.’

[15] Dimpy Mishra, in conversation with the author, Agra, November 2019.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Chaturvedi, ‘Salim Arif on theatre in Hindi heartland, sustaining movements, and the need for local support.’

Bibliography

Chaturvedi, Sumit. ‘Salim Arif on theatre in Hindi heartland, sustaining movements, and the need for local support.’ Firstpost.com. 2019. Accessed November 23, 2019. https://www.firstpost.com/living/salim-arif-on-theatre-in-the-hindi-heartland-sustaining-movements-and-the-need-for-local-support-6910201.html.

Das, Sisir Kumar. A History of Indian Literature 1911-1956: Struggle for Freedom: Triumph and Tragedy. New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi, 2006.

Khandelwal, Brij. ‘H1N1 claims Agra theatre personality Jitendra Raghuvanshi.’ Times of India, Agra, May 7, 2015. Accessed November 23, 2019. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/agra/H1N1-claims-Agra-theatre-personality-Jitendra-Raghuvanshi/articleshow/46488069.cms.

Richmond, Farley. ‘The Political Role of Theatre in India.’ Educational Theatre Journal 25, no. 3 (1973): 318–334.

Sharma, Rambilas. ‘Hindi Drama.’ Indian Literature 1, no. 2 (1958): 90–94.

Indira Gandhi National Open University (IGNOU). Natak Aur Any Gadya Vidhayein: Hindi Natak Aur Rangmanch. New Delhi: Manviki Vidyapeeth, Indira Gandhi Rashtriya Mukt Vishwavidyalaya, 2008.

Srivastava, Sachin. ‘Jo Bhi Ho, Hamara Swarnakal To Yehi Hai: Jitendra Ji Se Batchit- Sachin Srivastava Ke Saath.’ In Shabd Rahenge Sakshi: Jitendra Raghuvanshi, edited by Nawab Uddin, Pramod Saraswat and Dr Vijay Sharma, 69–79. Agra: Janman Samvad Kendra, 2015.