The caves of Aurangabad lie to the north of the city in the protective bosom of the Sihyachal ranges, and rise above the plains to a height of 700 feet. The caves overlook the present campus of Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar Marathwada University. Eclipsed by the close proximity of the World Heritage monuments of Ajanta and Ellora, this 2000-year-old group of caves stands in mute testimony to the ancient history of the city and to its gradual growth and transmutation into a modern vibrant city. The caves are within the city, approximately 8 km from the railway station, and behind the famous Bibi-ka-Maqbara.

The caves are bereft of inscriptions, and so the task of dating them and tracing their origins is a daunting one. In such circumstances, the dating can be based on a comparative study that aims to establish parallels—in themes, content, architecture, sculptures and pillars—with other similar cave temples.

Interestingly, a reference to the Aurangabad caves has been found at Kanheri, a group of cave temples in Mumbai’s Borivale National Park (Sanjay Gandhi National Park). In his book The Iconography of Buddhist Sculptures of Ellora, Ramesh S. Gupte notes an inscription in Kanheri’s Cave-IV which reads, 'Rajatalaka Paithana path asana chulika yu kuti kodhi' (Qureshi 1998). It can be translated as, 'In the paragana or taluka of Paithan called Rajatalaka (ancient Aurangabad) a small temple (kuti) and hall (kodhi) were erected at the Vihara of Sevaja.'

The inscription confirms that there were two caves of the early period—a chaitya and a vihara. The chaitya can be seen even today, and has close similarities with Cave 9 of Ajanta, which dates to the first century CE. However, the vihara, which was mentioned in the inscription, cannot be found. It could have been a small vihara that probably collapsed later due to the brittle nature of the basalt rock at Aurangabad.

The chaitya at the Aurangabad caves is the only early cave that was excavated during the later Satavahana period. It is numbered as Cave 4. Caves 1 and 3 belong to the later Mahayana period and have close parallels with Cave 21 and 24 at Ajanta, in terms of ground plan, pillar layout and detailing. Caves 1 and 3 at Aurangabad were carved during the Vakataka period. Caves 2 and 5 are unique in that they completely separate the main shrine from the back wall and place it in the centre of the hall. Caves 1 to 5 belong to the first group, towards the northwest of the city. There is a second group of caves towards the northeast: Caves 6 to 10, including a Hindu cave. There is a third group located behind Caves 9 and 10, but there are no sculptures there.

Literature Review

Most scholars underestimate the Aurangabad caves and treat them as insignificant; consequently, there is very little information available to tourists. In his Historical Researches, James Bird has written, 'The caves at Aurangabad are four in number and each assimilates so much in appearance to the other that an account of one would serve as a description of the whole' (Bird 1847). There is also a lot of confusion in understanding or identifying the sculptures and their stylistic and iconographic details.

The first account of Aurangabad caves was given by James Bird in 1847 in his 'Historical Researches', but his account was very short and incorrect. In 1858, John Wilson provided details of all the three cave groups; however, he could not identify Buddha’s attendants (Bird 1847).

In his Antiquities of Bidar and Aurangabad report, James Burgess gave the first detailed account of the three groups of the Aurangabad caves. At that time, the caves were covered with debris. From the presence of so many female sculptures, he felt that the cave might have been a convent for nuns. In The Cave Temples of India, James Burgess and Fergusson provide a more exhaustive report, in which they date the Aurangabad caves to the end of seventh century CE. They also provide the layout for the caves, describe the pillar decoration style and identify the attendants as well as most other sculptures. Ghulam Yazdani introduces Aurangabad, its geography, location and name, and the rivers and hills associated with the caves. He writes that the artists worked on hard rock; in case the rock turned out to be soft, the work was left incomplete.

M.N. Deshpande (Deshpande 1956) gives a short history of Aurangabad and goes on to describe each of the caves. According to him, the third group of caves at Aurangabad were not incomplete, but were left plain on purpose, and date to seventh century CE.

Douglas Barrett (Barrett 1957) was the first scholar to recognise and appreciate the architectural finery of the sculptures. He compared them to some of the best sculptures in both Ajanta and Ellora. In his book, Ajanta, Ellora and Aurangabad Caves, Gupte (Gupte 1962) opens with the origin of the name of the city and a brief introduction to Aurangabad and its caves, which he compares to the caves at both Ajanta and Ellora. Gupte (Gupte 1960-61) has also written an article on the Brahmanical caves at Aurangabad, a small cave in the second group, which shows strong influences of Hindu architecture and sculpture.

Two scholars wrote articles on the Aurangabad caves, in Marg, in 1963 and 1964. The first scholar, Mulk Raj Anand (Anand 1963) wrote an article titled 'Revaluation of Aurangabad Sculptures', in which he describes the sculptures chronologically, and identifies the dancing panel in Cave 7 as a Bharatanatyam pose. Anand felt that the artists had succeeded in creating a gallery of masterpieces in Cave 7 at Aurangabad.

The second scholar, Amita Ray, authored an article titled 'Aurangabad Sculptures' (Ray 1964). In the beginning, Ray briefly surveys the caves, their location and their historical, religious and economic background. She talks about the existence of a new form of Buddhism at Aurangabad and Kanheri, influenced by Yogachara and Vajrayana. Ray discusses in detail all the sculptures, and compares them with those in other contemporary caves.

Another writer, Deborah Brown (Brown 1964) writes that the style of the sculptures in the Aurangabad caves resembles both the earlier style, as in Ajanta, and the latter style, as in Ellora and Elephanta. Brown lists the details of each cave.

John Huntington uses East Asian Buddhist material in his article titled 'Cave-6 at Aurangabad' (Huntington 1981) to study Indian Buddhism.

The first full-bodied doctoral thesis on the Aurangabad caves was written by Dulari Qureshi (Qureshi 1998). For the first time, Qureshi presented an exhaustive and detailed documentation of the rock-cut caves of Aurangabad along with a critical analysis. This work attempted to identify the stylistic varieties and narrative techniques used in the Aurangabad caves and points out cultural affinities with other art centres such as Ajanta, Elephanta, Ellora, Kanheri, Sanchi, Gandhara, Mathura, Sarnath, Amravati and Badami. Her book, titled Art and Vision of Aurangabad Caves was published in 1998.

There are several other art historians, like Cunningham, Stella Kramrisch and Zimmer, who wrote about the caves of Western India and referred to Aurangabad caves in their writings. Carmel Berkson’s The Caves at Aurangabad: Early Buddhist Tantric Art in India is a significant work on the caves of Aurangabad. Other than a formalistic analysis of the carvings, her study also highlights the growth of Tantrayana as observed in the carvings of the caves of Aurangabad. Pia Brancaccio’s The Buddhist Caves at Aurangabad: Transformations in Art and Religion throws light on various factors, cultural, historical and religious, that might have formed a backdrop to the development of Aurangabad caves. Her concerns go beyond the iconography and chronology of the said caves and take into account international trade communities that might have influenced the developments in the caves of Western Deccan at large.

A cave-by-cave analysis would allow the reader a clearer understanding of the Aurangabad caves, the less known cave group squeezed between the more famous caves at Ajanta and Ellora.

Fig. 1. Cave 1 façade

First Group (Caves 1 to 5)

Cave 1

This is a vihara with an unfinished interior (Fig. 1). The roof and a major part of the porch is destroyed, probably due to the treacherous nature of the rock. At present, only four partially destroyed pillars remain. The veranda is 76.5 feet by 9 feet, and is supported by eight pillars and two pilasters. The wall of the veranda features two windows and three doors—a central door and two smaller doors. The hall of this cave is incomplete, but it was probably intended to be a 28-pillared hall. The layout of this cave is very similar to Cave 1 of Ajanta. The door jambs of this cave are especially interesting, but rather crude and unrefined. The couples carved on the door frame are in low relief. A nagaraja is carved at the base of the door frame. The hoods are now broken. Yakshis are carved as consorts of nagarajas. Even the windows of Cave 1 are surrounded by carvings. The lintel is divided into a number of compartments, each carved with an amorous couple.

Fig. 2. Buddha images in the veranda of Cave 1

Buddha sculptures: Three huge sculptures of Buddha are carved in the veranda (Fig. 2). The size of the sculptures reminds one of the later, gigantic sculptures carved at Ellora and Elephanta. One Buddha figure, at the extreme left of the veranda, measures 7.12 feet in height, 6.10 feet in breadth and 1.1 feet in depth. It is seated on a double lotus in padmasana, with hands in dhyana mudra, and is attended by Vajrapani on the right and Padmapani on the left. Between the door and window, at the left of the veranda, is the second Buddha sculpture, depicting the Miracle of Sravasti which can be seen also at Ajanta in Cave 1 and 17. Here, he is seated on a double lotus in padmasana, with his hands displaying the dharma-chakra mudra. The stalk of the lotus is supported by Naga kings. Above the Buddha’s head on either side are flying figures of dwarfs holding garlands. At the extreme right end of the veranda, another Buddha figure is carved seated on a double lotus in padmasana, with his hands in dharma chakra mudra. Figures of flying dwarfs holding garlands are carved on either side.

Pillars: The pillars in Cave 1 are especially attractive, due to the variety of salabhanjikas (tree goddesses) and figures of ganas (assemblage or troops of demon attendants of Shiva and devis) carved on them. A total of eight pillars support the ceiling of the veranda. Ganas accompany the salabhanjika figures, and are seen also on the four sides of the square bases of pillars.

In Cave 1, the pillars have a plain square base. Above the base is a shaft with a half-lotus design, above which is a floral band framed with beads and couples seated in the round. Ganas are carved on all four sides of the square base. Above the decorative shaft is a capital on which salabhanjika figures are carved.

According to U.N. Roy (Roy 1979), the idea of salabhanjika is associated with the miraculous birth of Siddhartha in the Lumbini gardens under the Sala tree. Since this was an auspicious occurrence, the custom of Salakrida evolved into 'Sala krida', a special festival held on the occasion of the anniversary of the Buddha. According to Rama Pisharot, the fruit or flower of a tree would bloom after the trunk would be kicked by a beautiful woman. Whatever the symbolic significance, the artist put bracket figures of tree goddesses effectively in a variety of poses.

Fig. 3. Tree goddesses as pillar brackets in Cave 1 veranda

The Aurangabad tree goddesses are some of the best examples of salabhanjika figures (Fig. 3). One of the most attractive examples is the sculpture of the tree goddess on the first pillar in Cave 1.The slim dryad is in a kashta type of saree and a blouse and is decorated with ornaments; the incised lines of the folds are clearly visible. A male attendant holds a flower vase, while a gana on the lower side seems to be supporting a mermaid above him. The head of the mermaid is seen to the left of the goddess, and her body near the goddess’ waist. The upper portion of the mermaid is a woman, while the lower portion is of a fish with scales. Above, the goddess holds a musical instrument known as lyre. This is one of the most unique sculptures.

Fig. 4. Gana figures on square bases of pillars

Ganas: According to sources, ganas are associated with Shiva and Ganesha. There are several interesting gana figures in Cave 1 (Katkar 1976) (Fig. 4). At the Aurangabad caves, most gana figures are short and have paunches, and are seen playing musical instruments.

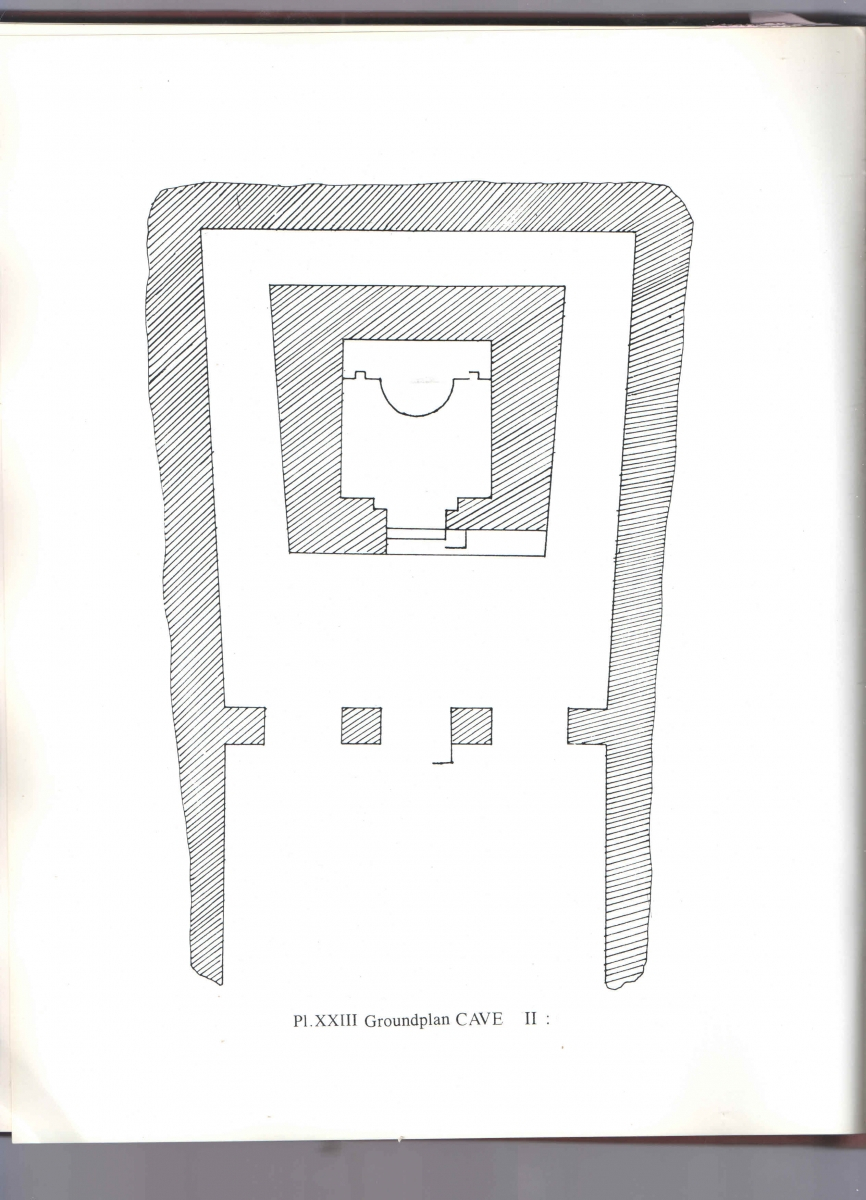

Fig. 5. Groundplan of Cave II

Cave 2

Cave 2 and 5 have a similar layout, with the shrine in the centre and a circumambulation path around the shrine (Fig. 5). The front of the cave has an open hall or veranda, which is 24 feet wide and 11.6 feet deep. It has two pillars, and corresponding pillars in front. It has a shrine in the centre of the hall, isolated from the back wall by an aisle on either side that is carved with figures of the Buddha. There are a number of panels of the Buddha that represent the Miracle of Sravasti.

Fig. 6. Preaching Buddha, main shrine of Cave 2

Inside the shrine is a huge figure of Lord Buddha measuring 7.10 feet in height and 4.68 feet in breadth (Fig. 6). The Buddha is seated in pralambapadasana and his hands are in the dharmachakra mudra. He is seated on a lion throne. The attendant figures are carved outside the shrine, one on each side. Maitreya is on the left and Padmapani is on the right, holding a rosary and lotus.

Fig. 7. Repeated carvings of Miracle of Shravasti on the walls of the pradakshinapatha

In Cave 2, the walls around the pradakshinapatha are completely covered with figures of the Buddha depicting the Miracle of Sravasti (Fig. 7). According to the Divyavadana, a Buddhist text (Lorousse 1959), this miracle occurred in a village called Srasvasti. Prasenjit, the king, organised a contest between Sakyamuni and members of the heretical sect. During this contest, Sakyamuni performed a number of miracles to convert the heretical sect. Nanda and Upananda, the Naga kings, created a miraculous lotus on the pericarp of which Buddha seated himself. Then, through magic, several lotuses were created out of this lotus, each of which formed a seat for the Buddha. In Cave 2 Buddha is shown seated on a lotus supported by the Naga kings, Nanda and Upananda.

Fig. 8. Cave 3 façade

Cave 3

Cave 3 is a vihara (Fig. 8). Originally, it had a veranda, which supported four pillars. It had chapels or cells on elevated platforms on either end as can be seen from the remains. The veranda is 30 feet long and 8 feet wide. The entrance wall has a central door and two windows on either side. The hall of this cave has 12 pillars—four on each side—with a square space in the centre. The hall measures 41.3 feet in length and 42.11 feet in width. There are two cells on either side of the hall, at the extreme ends of the aisle, and a chapel of each in the centre. There is an antechamber (antarala) at the rear of the hall and a shrine (garbhagrha) in the centre. There are no cells towards the rear of the hall.

The door of the shrine is very decorative; the arch has floral designs on both sides. Naga guardians are carved on the base on both sides of the door. Above this is a panel of ganas, and above the panel are couples in an amorous mood. There is a pilaster in the design of a twisted rope on both sides of the door, and salabhanjika figures atop each pilaster.

Fig. 9. Pillared hall of Cave 3

In Cave 3, pillars both support the cave and heighten its beauty with carvings of variegated flowers, trees and animals, ornamentatal and geometrical designs and, above all, alluring and enchanting tree goddesses (Fig. 9). The pillars have square bases, and each corner of the base has a dwarf carved on it; the pillar shafts have perpendicular or spiral flutes carved with bands of elaborate tracery, floral and leaf patterns. The pillar capitals have bracket figures. The pilasters are also beautifully decorated. Above the front group of pillars is a frieze of a jataka tale, the Sutasoma Jataka, which can also be seen in the paintings at Ajanta. There is a great deal of similarity between the sculptural frieze at Aurangabad and the paintings in Cave 17 of Ajanta.

The main shrine has a slightly damaged figure of the Buddha at its centre. The Buddha is seated on a double lotus in a teaching posture in pralambapada asana. Attendants stand at both sides. There are also flying apsaras and dwarfs, and crouching elephants on both sides of the Buddha.

Fig. 10.1. Devotee figures in the main shrine of Cave 3

Fig. 10.2. Devotee figures in the main shrine of Cave 3

Fig. 10.3. Sketch of devotee figures in the main shrine of Cave 3

But the most ingenious and subtle creations of Cave 3 are the fully rounded figures of devotees who sit in the shrine on both sides of the central Buddha figure (Fig. 10). The arrangement and disposition are simply breathtaking. The images are huddled in a corner, worshipping the Buddha in silent adoration with utmost respect and awe. The perfect anatomy of these devotee figures gives one the impression that the artist not only imagined the figures, but must have initially made a few people model for the scene, to create such realistic images. In dark corners, the images appear lifelike; their facial features and hairstyles, with ringlets and rolled layers, make them look like Greek figures.

Fig. 11. Cave 4, chaitya

Cave 4 (chaitya)

Cave 4 in Aurangabad is a square chaitya cave that measures 30.9 feet by 23 feet (Fig. 11). It is similar to Cave 9 of Ajanta, a square chaitya cave approximately 45 feet by 23 feet. The flat ceiling over the side aisles shows that the chaitya at Aurangabad was built at a slightly later date than the chaitya at Ajanta. Despite their later excavation, the pillars are simple and octagonal, and slope inwards. The façade is entirely of stone, though a major part has collapsed.

The chaitya of Aurangabad has vaulted stone ribs. A part of the ceiling is destroyed. The entablature (upper part of a column) is decorated with arched windows (miniature). The beam railings are an unconventional emblem of early Buddhist religious structures. The pillars are all octagonal, and do not have a base or capital. Unfortunately, all the pillars were destroyed by time and the vagaries of nature. Only one pillar remained; its lower portion, which is still intact, gives an idea of the original design. The rest of the pillars have been reconstructed by the Archeological Survey of India. The stupa has a round base and is topped with a harmika with a railing design. Above these are three steps. Above this was a chhattra (umbrella) which is now destroyed. The stupa too is partially destroyed. The stupa is 5.8 feet in diameter. This cave has a square end at the rear, unlike other caves, which have an apsidal end. Even the ceilings on the aisles are flat. As mentioned earlier, the entire façade has vanished. The decorative elements of the chaitya include stepped merlons (tooth-like structures), which are also carved in the chaityas at Bhaja, Kondane, Ajanta Caves 9, 2 (vihara) and 30 and at Pitalkhora.

This cave has been mentioned in an inscription at Kanheri, which talks about a chaitya and a vihara carved as an endowment in the taluka of Paithan called Rajatalaka (ancient name of Aurangabad).

Fig. 12. Cave 5

Cave 5

The first cave with a shrine isolated from the back wall, this was probably a bigger cave, with cells on both sides of the now ruined veranda (Fig. 12). This cave appears to be extremely crude. It was probably the first attempt at a new form. The artists were not too sure of themselves, as is obvious from the nature of the carvings, and their immature and unrefined forms. None of the other caves are so crude.

At Ajanta, in Caves 1 and 16, the image of Buddha can be circumambulated, but the main shrine is attached to the back wall. In Cave 5 of Aurangabad the image of the Buddha is seated in padmasana with his hands in dhyanamudra. On his right is Vajrapani, and on the left Padmapani. The Buddha is seated on a rectangular pedestal, instead of the usual lotus pedestal, and there are none of the usual side images of elephants or dragons. That is why many mistook it to be a Jaina cave.

Fig. 13. Buddha figures carved in Cave 5 shrine

However, there are panels of the standing Buddha on the left wall of the shrine (Fig. 13). The shrine door is plain; this is different from all the earlier caves, where the shrine doors are well decorated. A number of figures of the Sravasti Miracle are carved on the wall of the shrine.

Fig. 14. Cave 6 façade

Second Group (Cave 6 to 9), Ganpatya cave, and Cave 9 and 10

Cave 6

Cave 6 is a part of the second group of caves (Fig. 14). A few kilometres separate the first and second groups of caves, though both groups have been carved out of the same mountain range. A Ganapatya cave is also located in the same series; hence, there is a total of six caves in the second group.

The veranda of Cave 6 was supported by four pillars; unfortunately, only the lower portion remains. On the left of the veranda is a porch. The temple combines the characteristics of later Ajanta vihara-cum-monastery caves. Cells are carved on the right and left of the hall.

The antechamber and the shrine are carved on a platform, which is raised higher than the rest of the hall. The antechamber has two pillars and two pilasters. Generally, the pillars have a square base, above which is the shaft carved with ganas on the four corners, or amorous couples. On the top salabhanjikas are carved as bracket figures. Most of the pillars have full or half lotus medallions.

Here, again, there is an advancement in the layout, in which the main shrine is isolated from the back wall, and there are two subsidiary shrines, each housing a Buddha image, on both sides of the back wall.

Fig. 15. Cave 6, main shrine dvarapala

In the main shrine, the entrance door is protected by two huge dwarapalas (Fig. 15). Measuring 10.5 feet, these are taller than the earlier sculptures. Flying couples and dwarfs are carved above these dvarapalas. A figure of Tara is carved on the right side of the male attendant on the left. This male attendant is identified as Maitreya. A stupa and a Buddha figure seated in padmasana are carved on his crown. His right hand displays vitarkamudra.

Inside the main shrine is the usual image of Lord Buddha seated in the western style and hands dispalying the dharma-chakra mudra. He is seated on a lion throne surrounded by the usual figures of crouching elephants, vyalas, makaras, etc. There are chauri bearers on both sides.

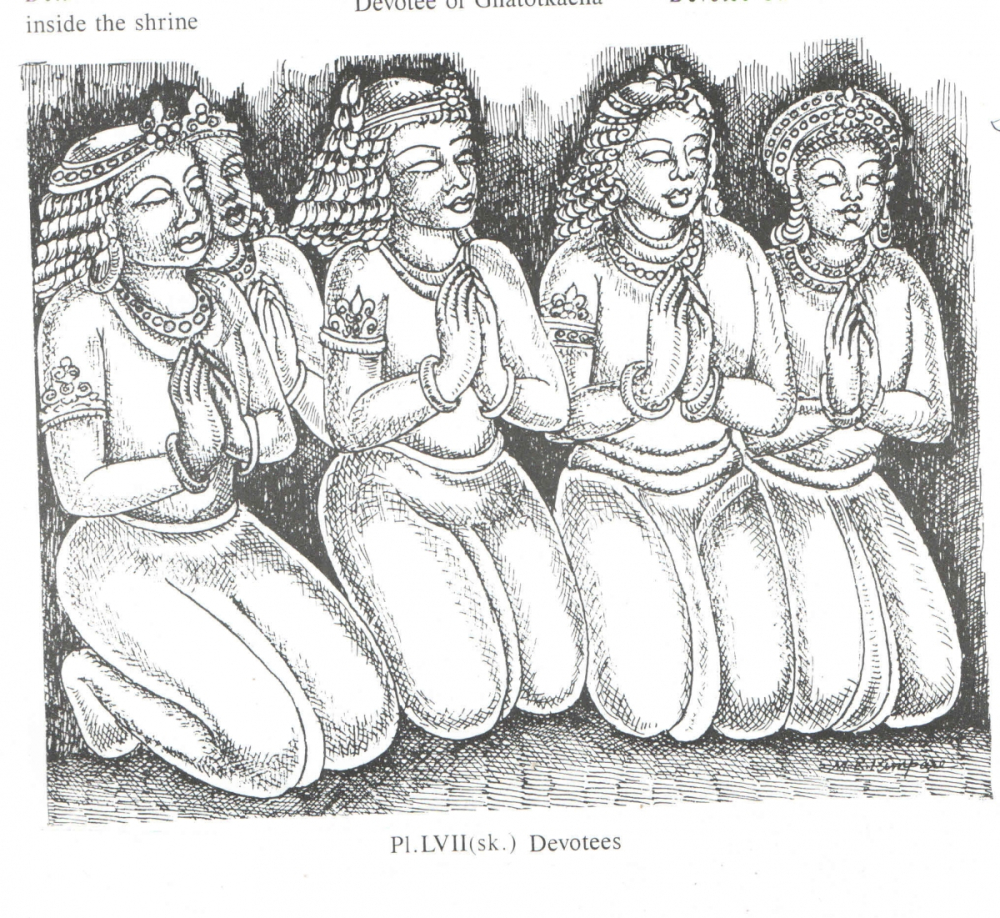

Fig. 16.1. Devotee figures inside Cave 6

Fig. 16.2. Devotee figures inside Cave 6

There are figures of kneeling devotees carved inside the shrine–five male devotees to the left, and five female devotees to the right (Fig. 16). However, this group of figures lack the energy, life-like vigour and realism seen in similar figures carved in the shrine of Cave 3. The work is of inferior quality.

Fig. 17. Ganapatya cave

A small Ganapatya Cave

This cave was discovered in 1959 by the historian Ramesh S. Gupte (Fig. 17). This cave lies on the lower left side of Cave 6. It is very insignificant in size and dimension. It is only 10.11 feet in breadth, 13 feet in depth, and 6.10 feet in height. Two pillars and pilasters support the ceiling of the cave.

Fig. 18. Saptamatrikas

Fig. 19. Ganesha figure in the central wall

Fig. 20. Buddha images on the right of Ganesha

On the left wall of the cave, a panel of saptamatrikas is carved, with Virabhadra on the extreme left and six matrikas in a row (Fig. 18). The seventh matrika, Chamunda, is carved on the front, as there is not enough space on the left. The central position is occupied by Lord Ganesha; the figure of Durga is carved on his right (Fig. 19). There is an image of Buddha carved on the right wall of the cave. Two images of the Buddha—one with attendants and the second without attendants—are all but effaced (Fig.20). The amalgamation of two faiths—Brahmanical and Buddhist—can be witnessed in this cave. Its workmanship is substandard, but it is an important cave since it is the only Brahmanical cave in the Buddhist complex.

The saptamartrikas carved on the left wall along with Virabhadra include Brahmani, Maheshvari, Kaumari, Vaishnavi, Varahi, Chamunda and Durga (Sahai 1975).

Fig. 21. Bodhisaktis flanked by Buddha and Avalokiteshvara

Cave 7

Ground plan: This completely intact cave is the most developed one among all the three groups. It has a veranda in the front supported by four pillars and two pilasters. The veranda measures 34 feet in length and 14 feet in breadth. On both sides of the veranda are two chapels which are raised by a few steps, and both chapels are supported by two pillars and two pilasters. On the left chapel is a panel of Buddhist saktis, all standing; a Buddha figure is carved on one end and Avalokitesvara on the other (Fig. 21). These saktis are identified as Tara figures of the Tantrayana cult; some other scholars identify them as dakinis. Alice Getty feels that they are dakinis (Getty 1928), as they are generally depicted in a standing position.

Fig. 22. Hariti and Pancika

The figures of Hariti and Pancika are carved in the opposite chapel (Fig. 22). They represent the ancient trend of yaksha worship (Coomaraswamy 1971). Hariti was the patroness of children and fertility (Gupte 1964).

The back wall of the veranda has windows on both sides and a central door. The door leads to another hall, which is on a higher platform. The lintel of the door is decorated with mini shrines. There is a pilaster design on both sides of the doorway and decorative carvings around both windows. There are several figures around of Ganesha, Nandikesvara and Varaha, and a figure of Gajalakshmi on the top (Fig. 23). There is a dvarapala on each side of the door.

Fig. 23. Gajalakshmi

Fig. 24. Main shrine flanked by Tara figures; view of pradakshinapatha around main shrine

The main hall, mentioned earlier, is slightly elevated. The shrine is carved in the centre of the hall. There are two Tara figures on both sides of the door to the shrine (Fig. 24). Chaitya windows are carved on top of the door. The shrine doorway has Naga guardians and a pilaster design.

Around the shrine is a circumambulation path. There are shrines at the extreme end of each side corridor; a Buddha figure is carved in each of these shrines. Three cells are carved along the corridor on each side of the hall.

This layout, perfectly balanced on each side, is one of the most advanced seen in the Buddhist architecture of the period.

Fig. 25. Ashtamahabhaya Avalokiteshvara (left) and Manjushri (right) flanking the main shrine door

Fig. 26. Detail of Ashtamahabhaya Avalokiteshvara

Sculptures: On either side of the veranda, on the back wall, two huge sculptures are carved: Avalokitesvara on the left and Manjusri on the right (Fig. 25). Avalokitesvara stands in the samabhanga pose. His left hand is in abhaya mudra, and his right hand holds a lotus stalk. He wears a jatamukuta; the figure of Buddha Amitabha is carved on the mukuta. Above his head are flying dwarfs. On either side of Avalokitesvara are people facing various dangers while travelling through jungles or by ship. Eight perils are depicted here (Fig. 26). They are fire, robbery, slavery, drowning, attacks by lions, snakes, attacks by elephants and an ogress. Near each scene, Avalokitesvara is shown in a flying position; he is shown arriving just in time to save his devotees. This is one of the best sculptures at Aurangabad. The eight dangers are also known as ‘Mahabhaya’ (great dangers). According to Gupte, this composition is one of the most magnificent ones in Western India.

Fig. 27. Manjushri

Manjusri: On the right side of the back wall of the veranda is the figure of Manjusri, an important Bodhisattva, who is given a place of pride in the Buddhist pantheon (Fig. 27). Manjusri’s right hand is on the kati (knot of the garment), and his left hand is raised as though in abhaya mudra. He is accompanied by two attendants, one male and one female.

Main Shrine: The shrine is carved in the centre of the main hall. On each side of its entrance door are carved two voluptuous Tara figures. Both the figures are very prominent. The hairstyles are beautiful and elaborately decorative.

Fig. 28.1. Tara figure on the right of the shrine

Fig. 28.2. Detail of Tara figure

Tara figure on the right of the shrine: On the right of the shrine is one of the most beautiful figures in Western India. She stands in the tribhanga position and wears heavy jewellery and the most remarkable hairstyle (Fig. 28). Her headdress is decorated with a rosette, lotus flowers, beaded strings, etc. The top part of her earlobe is decorated with earrings. Female attendants stand on both sides, also wearing the most decorative hairdos. On the right, the female attendant is attended to by a female dwarf. A male attendant stands at the other side.

Fig. 29. Tara figure on the left

Tara figure on the left side of the shrine: This Tara figure is extremely voluptuous and graceful (Fig. 29). She stands in the tribhanga pose. Unfortunately both her hands are broken. In her right hand she holds a lotus, as is clear from the lotus stalk. She wears a heavy hairdo decorated with pearl strings, lotus flowers, rosettes, leaves and a crescent motif. She has a female attendant, who is, in turn, attended to by a female dwarf. On the left is a deformed attendant, standing with both legs bent at the knees and holding a crooked stick and a queer headdress of five knots.

Fig. 30. Buddha figure in the main shrine

Inside the shrine: The main figure, Lord Buddha, sits inside the shrine (Fig. 30). He is seated on a lion throne in the teaching posture. On each side is carved vyala figures and crouching elephants. There is a makara on the top, and also flying couples holding garlands.

Fig. 31. Dancing panel in main shrine, Cave 7

On the left side of the shrine is the famous Dancing Panel (Fig. 31). This is one of the most unique dancing panels. The central dancer is performing nritya with complete dedication. The dancer is oblivious to everything around her and is concentrating completely on the movements of her feet, hands and eyes. Perfect coherence of various movements best characterizes this Bharatanatyam pose. The orchestra is composed of women playing musical instruments like mridanga, flute, cymbals and damaru. This panel is unifocal, as there is only one dancer; the other figures in the composition are musicians.

Cave 8

This is a small cave adjoining Cave 7. Cave 8 can be accessed through a staircase on the veranda of Cave 7. Cave 8 has two cells carved into the left of the hall and three cells carved into the back wall. The second and the third cells on the left are incomplete. Two Buddha figures are carved on each side of this small cave. A Buddha figure is seated in padmasana, and his hands are in the dhyana mudra. The centre of the cave has a homa kunda, which was probably carved in a later period.

Fig. 32. Exterior of Caves 9 and 10

Caves 9 and 10

Both these caves have been carved a little further from the other caves and are higher up the hills. It was formerly a huge hall with separate compartments and three separate shrines. But, unfortunately, due to the soft or brittle nature of the rock, the entire façade has collapsed. The front hall of the cave measures 85 feet in length and nearly 19 feet in depth (Fig. 32). At the back of the open halls are three separate halls, each leading to a shrine, though the major part of the cave is unfinished. In the centre of the cave is the main shrine, with an antechamber supported by two pillars, and a big hall measuring 29.1 feet by 14.2 feet with a number of sculptures. The main hall is supported by four pillars while the halls of the subsidiary shrines are supported by two pillars.

Fig. 33. Mahapainirvana; Avalokiteshvara figure seen on the right

Fig. 34. Detail of Avalokiteshvara figure

Fig. 35. Tara figures carved on the wall

Sculptures: At the entrance to the hall, to the left of the first shrine, is a sculpture showing the Mahaparinirvana scene, where the Buddha bids mother earth farewell and takes refuge in heaven (Fig. 33). Another important figure on the side of the Mahaparinirvana sculpture is that of Padmapani in the form of Avalokitesvara, known as Sadaksari Avalokitesvara (Fig. 34). It is a standing image with four hands. He wears a jatamukuta, with a figure of the Buddha in the crown sitting in padma-asana with hands drawn in dhyanamudra. He holds a rosary in the upper right hand and a lotus stalk in the left hand. His lower right hand is in the varadamudra. There are several other sculptures in the hall, a number of Tara figures (Fig. 35) with striking headdresses, and figures of Padmapani, Manjusri, etc. There are several figures of the Buddha inside and outside the shrine.

Fig. 36. Kubera and Naga figures flanking the main shrine door

Outside one shrine are Naga guardians on each side, and on each side of the back wall are two figures of Kubera (Fig. 36).

Third Group

Caves 11 and 12: These are located at the rear of the hill and consist of a simple hall and plain pillars. It is devoid of any carving.

References

Anand, Mulk Raj. 1963. ‘Revaluation of Aurangabad Sculptures’, Marg 16. Bombay.

Barrett, Douglas. 1957. A Guide to the Buddhist Caves of Aurangabad. Bombay.

Bird, James. 1847. Historical Researches on the Origin Principles of the Buddha and Jain Religion in the Caves of Western India. Bombay.

Brown, Deborah. 1966. ‘Aurangabad: A Stylistic Analysis’, Artibus Asia 28.

Burgess, James. 1972. ‘Antiquities of Bidar and Aurangabad Report 1875–76’, ASWI 13.

Burgess, James, and James Fergusson, eds. 1969. The Cave Temples of India. London.

Coomaraswamy, A.K. 1971. Yaksas (Part I and II). Delhi.

Deshpande, M.N. 1956. ‘Pratishthan’, Souvenir 7.

Gupte, R.S. 1960-61. ‘A Note on the Brahmanical Cave of the Aurangabad Group’, Marathwada University Journal 1.

Gupte, R.S. 1962. Ajanta, Ellora and Aurangabad Caves. Bombay.

———. 1964. The Iconography of the Buddhist Caves of Ellora. Aurangabad.

Getty, Alice. 1928. The Gods of Northern Buddha. Oxford.

Huntington, John. 1987. ‘Cave Six at Aurangabad’, in Kaladarshana: American Studies in the Art of India, eds. G. Johnna and G. Williams. Oxford: 1 BH Publicity.

Ketkar, Shriddar. 1976. ‘Aurangabad Leni’ (Marathi), Vishvakosh 4.

Larousse. 1959. Encyclopaedia of Mythology. London.

Pisharoti, Rama. ‘Salabhanjika’, Journal of India Society of Oriental Art 3.

Qureshi, Dulari. 1998. Art and Vision of Aurangabad Caves. Delhi.

Ray, Amita. 1963. ‘Aurangabad Sculptures’, Marg. Bombay.

Roy, U.N. 1979. Salabhanjikas. Allahabad.

Sahai, Bhagwant. 1975. Iconography of Minor Hindu and Buddhist Deities. New Delhi.

Wilson, John. 1858. ‘Caves Near Aurangabad and Ellora’, YBBRAS 4.

Yazdani, Ghulam. 1937. The Rock Hewn Temple of Aurangabad. London.