Analysing two paintings on the nine rasas of Krishna’s leelas, Prof. B.N. Goswamy is fascinated by how how two different painters—separated by more than a century and a half of time and by hundreds of miles—not only turning to the same poetic text and thus bonding together, but bringing their own understanding, or utsaha, to the task in hand. (Photo courtesy: The Tribune)

This article appeared originally in The Tribune, Chandigarh and is reproduced here with permission.

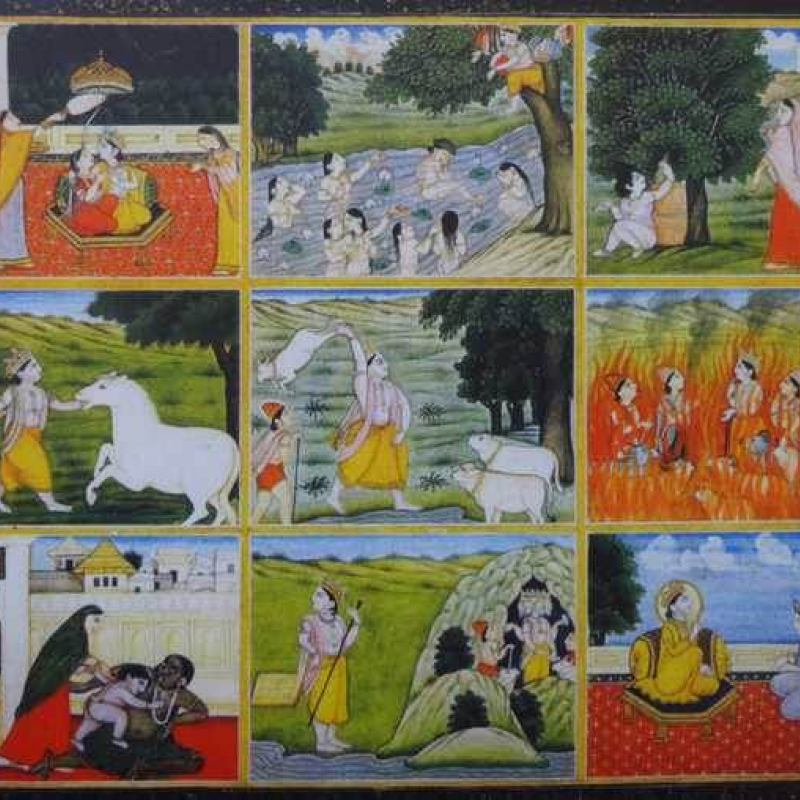

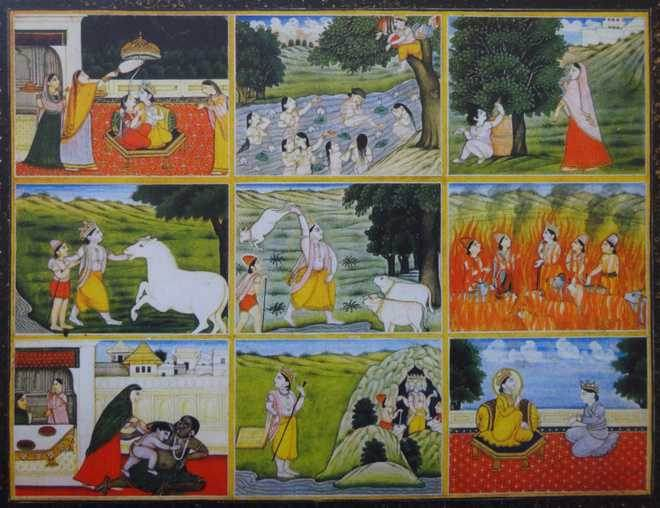

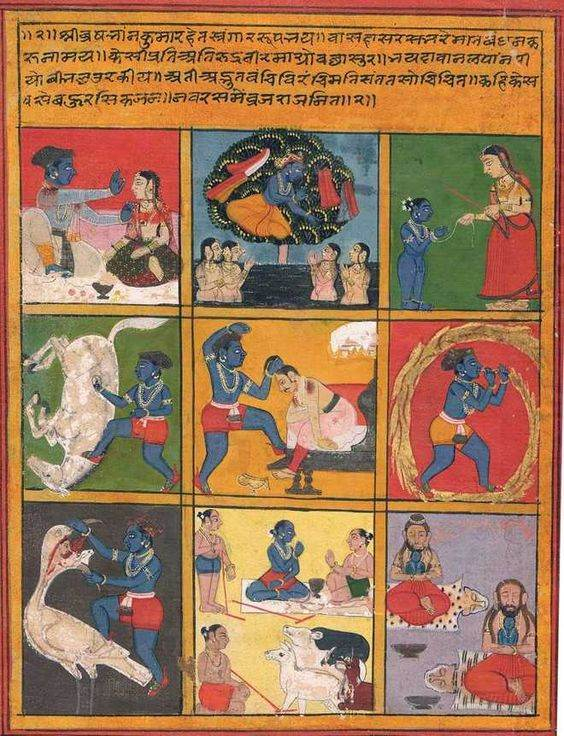

Rummaging through some old files the other day, I came upon a greeting card which Mr Chhotey Bharany, the well-known collector and art-dealer, had sent me years ago. There was no date that I could relate it to, nor the occasion, but the image on it had stayed in my mind: a Pahari painting, from the early years of the 19th century, depicting within one frame nine episodes from the ‘leela’ of Krishna. Even when I had received the card, the image had reminded me vaguely of a Rajasthani painting of the same theme that I had seen somewhere, but I was not sure. And then, all of a sudden, everything came together: from the archives of images of paintings that I—very inefficiently, I need to add—keep, quite unexpectedly that Rajasthani painting—it was from Mewar—jumped out. This too had nine panels within one frame, and each of them treated of an episode from the great ‘leela’. With some eagerness, I sat down to compare the two works.

Neither of them is truly a great painting, but I found them of great interest. For, to the natural question that arose in the mind—why would the painter pick these nine episodes from among the countless that constitute the leela of Krishna?—one of them provided a clear answer. It lay in the four lines of Hindi verse written in Devanagari characters, which were inscribed at the top of the Rajasthani painting. The words were those of the celebrated sixteenth century poet Keshavadas and came from his classic work, the Rasikapriya. Singing as he so often did of the deeds of Krishna, in these lines the great poet strings nine of them together to refer to the nine different rasas that reside in them.

One might have to pause here a bit, but there is much recompense in what follows. The rasas, sentiments or flavours as one tends to call them—the age-old concept of rasa, as almost everyone knows or needs to know, is one of the pivots of the Indian aesthetic theory—one is, of course, familiar with: shringara, hasya, karuna, raudra, and so on. It is truly hard to grasp in a few words the concept with all its subtleties, but, baldly put, the rasas or sentiments/emotions that remain embedded in some great art, and that the viewer or reader can experience if he is a rasika, are: love, laughter, compassion, anger, valour, fear, disgust, wonder and quietude. As he proceeds with taking these up, in relation to the leela, Keshavadas opens with the line: “Shri vrishbhanu kumari hetu sringara rupa bhaye.” In other words, “for his beloved, Radha—Vrishbhanu’s daughter—he (Krishna) was all shringara,” that is love as embodied in the erotic sentiment. From here, on to hasya or laughter, for which he hid the gopis’ clothes as they bathed. And so on.

Also read | Nathdwara Paintings: Shrinathji Cult, Haveli Traditions and Bazaars

Following this line, both the Rajasthani and the Pahari painters, brought in, in the form of separate panels within the same painting, the episodes from Krishna’s life that they must have rendered in separate paintings time after time while treating of a text like the Bhagavata Purana. The bond between the child, Krishna, and Yashoda, his mother, even when she punishes him for some prank of his, is evoked through karuna or compassion; raudra, fierce anger, takes the form of Krishna killing the demon who comes in the guise of the horse, Keshi; vira or the rasa of valour, the Rajasthani painter renders through Krishna killing his evil uncle, Kamsa, while the Pahari painter shows Krishna overpowering the calf-demon Vatsasura. For bhaya, interpreted as fear, both the painters turn to the exploit of Krishna drinking the forest fire, daavaanala-aachaman, even though their renderings of that great deed is of different orders; bibhatsa, the rasa of disgust, sends the two painters in different directions, for the Rajasthani painter interprets the poet’s word, baki, as a reference to Krishna having mastered baka, the stork-demon, who swallowed the Lord and his companions only to die at his hand.

Also see | Raas Leela Costume: In Conversation with Laishram Sharat Kumar Singh

The Pahari painter, decidedly correctly, knows baki as another name of the ugly demoness, Putana, whose breath the infant Krishna sucked away as she suckled him at her pendulous breasts. In the rendering of adbhuta, the wondrous, both the Rajasthani and the Pahari painter recall the episode of Krishna breaking the pride of Brahma by creating almost a parallel reality showing his cowherd companions at two places at once; and, finally, the shanta rasa of quiescence is shown by the Rajasthani painter as devotees and yogis sitting in meditation with Krishna in their hearts, while the Pahari painter shows a devotee kneeling before Krishna and quietly listening to him speak.

All this may not be of great interest to many, but to me it is. For here one sees two different painters, separated by more than a century and a half of time and by hundreds of miles, not only turning to the same poetic text and thus bonding together, but bringing their own understanding, or utsaha, to the task in hand. And they, one remarks, are not very far from each other in spirit.

This article has been republished as part of an ongoing series Art N Soul from The Tribune.