Nathadwara is a small town some 40 kilometres north of the Udaipur city in Rajasthan. In nathadwara, Udaipur, Rajsamand district and the places around, most of the buildings have their doorways flanked by paintings of elephants with mahauts, tigers, peacocks and bejewelled females. Shrinathji, the principle deity of Nathadwara is a living deity for the devotees and therefore the place where Shrinathji resides is called haveli. The structure of the haveli consists of various rooms linked by verandas, passages and courtyards, which is very different from temple architecture.

Doorway of the haveli at Kankroli, Rajasthan

Iconography and Legend of Shrinathji

Idol of Shrinathji lifting Mount Govardhana

The Shrinathji idol is the principal deity of the Nathadwara haveli, always shown with his left arm raised above his head lifting Mount Govardhana, while his other hand rests on his waist. The belief is that the image was taken out of Mount Govardhana in 1479 when Vallabhacharya was born. In 1493, he arrived at Govardhana with two disciples and decided to construct a temple but due to attacks, destruction and looting by different armies, the image travelled through many regions for number of years.

Finally, Raja Raja Singh of Mewar announced he would offer shelter to the idol, but the chariot of Shrinathji got stuck at Sinhad near Udaipur. Taking this as a sign from Shrinathji to stay here, they decided to not to proceed further and Sinhad became the final dwelling of Shrinathji.

Symbolic expressions are also involved in various shringaras of Shrinathji. The U-shape tilak on the forehead represents the impression of Radha’s foot and the lotus garland is symbolic of Radha’s heart which Shrinathji keeps close to his own heart as an acknowledgement of love and dedication. The small Yamuna water container placed on the pedestal represents mother Yashoda and the throne on which the image rests is Yashoda’s lap. The lotus-shaped eyes of Shrinathji are also compared with Kamadeva’s bow.

Nathadwara Paintings

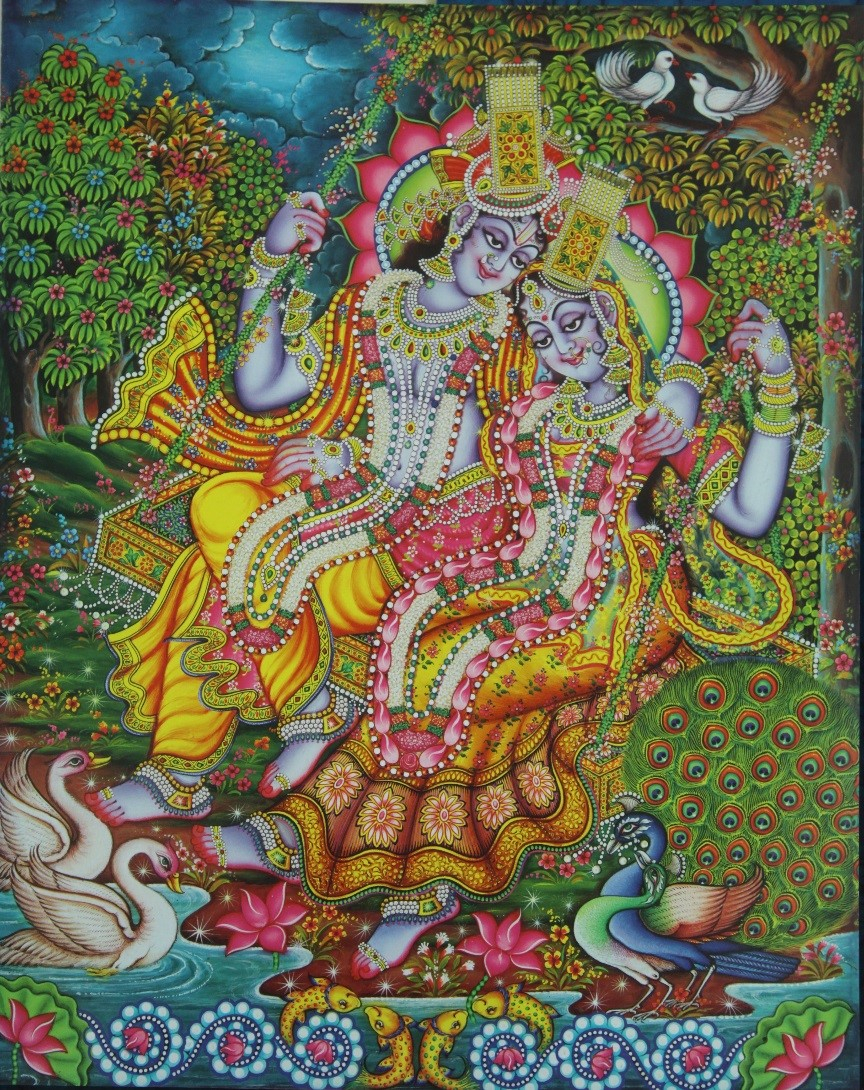

Nathadwara is the present headquarters of the Pushti Margiya Vaishnavite cult. The art practice includes haveli-painting traditions like pichhvais—textile wall hangings as the backdrop of Srinathji, and other embroidered designs and murals, where hundreds of artists work under a mukhiya (chief painter) to decorate temple rooms. The painting tradition of the Vallabha Sampradaya (Pushti Margiya Vaishnav Sampradaya propagated by Vallabhacharya) can be traced back to the Krishna Lila mural in Vallabhacharya’s father’s house. Before Diwali or annakuta festival, different entrances of different havelis of Nathadwara are whitewashed and repainted. The haveli painting tradition emerged in the 19th century as the ‘Nathadwara school’ which flourished and developed mostly through the influences of Rajasthani schools, especially Mewar and Kishangarh. In response to various rituals, several categories of pichhvais, paintings and murals evolved under the patronage of Tilkayats-Goswamis (chief priests of havelis) and individuals who offered creative freedom to the artist within the limitations set on different genres of icon paintings, mythological paintings, manoratha, Krishnalila, portraits, landscapes and other secular subjects. Painted pichhvais usually show whisks on either side of a kadamba tree; in such cases the tree symbolises Krishna when he disappeared from Vrindavana, leaving the gopis alone. But it is the image of Shrinathji which is popular among devotees and clients. These images usually depict daily darshanas, festival shringaras, chhappan bhog etc.

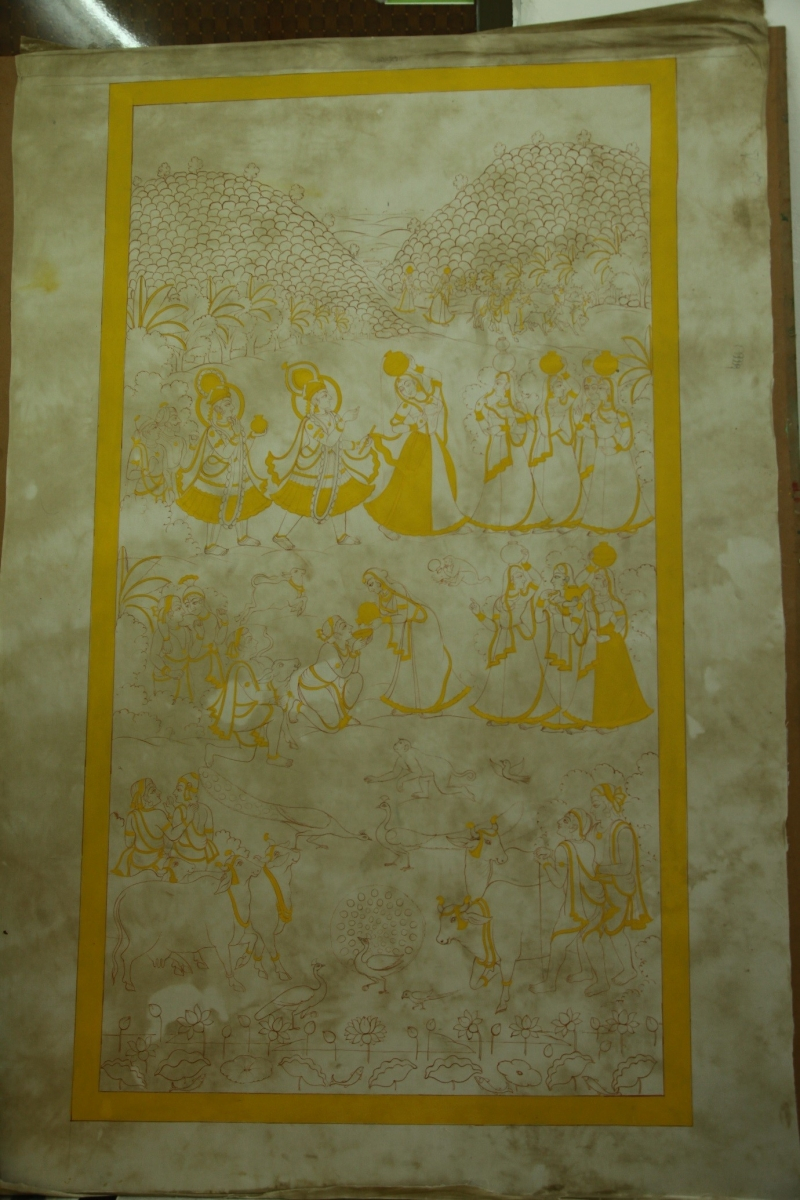

Nathadwara paintings display a high degree of skill in draughtsmanship, portraiture and in composition. In manoratha paintings, the Shrinathji idol is always shown with goswamis and often patronised by a wealthy devotee who takes care of the expenses of a particular darshana and seva. The devotee also commissions a painting to commemorate this event, which usually depicts the devotee and family members on both sides of Shrinathji. Krishna Leela paintings depict Krishna’s childhood and scenes from his early life in Gokul such as playing in Yashoda’s lap, stealing butter, Ras Leela with Radha and other gopis, lifting Govardhana mountain etc.

Pichhvai of Sharad purnima Ras-Leela

Eclectic Nature of Tradition

Nathadwara is a meeting point of various styles because painters of this school have migrated from places representing various Rajasthani traditions of painting. Nineteenth century academic realism, portrait painting and the invention of photography also inspired traditional practitioners. Painters of the Nathadwara tradition generally come from three different castes—gauds, jangids and purbia. Gauds and jangids claim to be Brahmins and are believed to have migrated from Udaipur, Jodhpur and Jaipur. But at other times they have denied the claim and have declared that they were originally carpenters (according to R.N. Mehta). Purbias claim to have migrated from Delhi and Alwar, and were selected by the patron based on their caste affiliation and not expertise. Painters of Brahmin lineage were appointed to serve elite patrons.

Harishchandra Swarnakar, Krishna-leela painting illustrated for 'Yamunashtakam Granth', Acrylic on canvas

During the 19th century the quality of traditional art was affected by the introduction and arrival of European artefacts, the printing press and photography. Therefore, in Nathadwara, Krishna Leela paintings turned into a blend representing traditional and modern tastes. In manoratha paintings, an almost photographic likeness was seen in the portraitures. Sometimes, actual photographs of donors/devotees were pasted on these paintings. Present day pichhvais used in Nathadwara haveli are from the 19th and early 20th century. From these, very few are replaced and very few added, because many of the leading artists are either dead or are not replaced by the temple authorities. Decline in patronage of the Tilkayats resulted in popular paintings being sold as marketable goods demonstrating different episodes like the life of Krishna, Krishna Leela, and miscellaneous patterns such as peacocks, cranes, monkeys, coloured fields with contrasting borders, or embroidered floral patterns to attract secular patrons and connoisseurs.

Present Art Practices: Popular and Commercial

The popularity of icon paintings, Krishna Leela and manoratha paintings are unchallenged since the late 19th and early 20th centuries. At the same time styles and materials which are employed to prepare sectarian painting have entirely changed after over two centuries of practice. Nathadwara is one of the most sacred places of pilgrimage for the Vaishnavas, and the need for religious souvenirs, like cheap reproductions of Krishna Leela pictures, has become a fashion. Brijbasi & Sons, Harnarayan & Sons, Narottam Narayan Sharma among others, began to produce oleographs and prints of the Nathadwara ‘theme’ and also recontextualised Vaishnava iconography to depict nationalist subjects.

Popular paintings and prints of nathadwara

Nowadays, artists accept commissions from individual connoisseurs, earth colours and traditional brush works are replaced by canvas, and acrylic colours and spray guns are used to give a painting a finished look ready for sale in the market. Such souvenirs have became a part of popular visual culture in Nathadwara, as have diamond-studded and embellished wooden cut-outs of the Srinathji icon with painted backgrounds and the availability of images of the icon in printed format on various utility goods including costumes.

Popular image production, Wooden cut-outs to be painted and decorated with gems and jewellery

The merchant community, especially of Western Indian, are known followers of the Vaishnavite cult. References to trading and monetary transactions are found in Bhakti poetry of Vaishnava saint poets, e.g., one of Narsinh Mehta’s works, 'mari hundi swikarjo re laal...' Further, Srinathji himself is considered to be the god of wealth and calling Banvari to Krishna is also a common practice in north India (which later spread all over). Now, it is curious to study how these economic concerns have influenced the cult and artists to make themselves financially competent. This is an observation made only at early stage, which needs a proper enquiry.

These days due to recent technology many changes have taken place in the visual culture of the Vaishnava sampradaya but there are practising painters who continue to survive in Nathadwara and Kankroli and also train the next generation. But the number of painters in Nathadwara is reducing day by day, a sign of the need for informed patronage to produce artistic excellence.

Practising Artists of Nathadwara and Kankroli

Harishchandra Swarnakar: Trained under Shree Anil Parikh, Nathadwara. Practising this art for 28 years, associated with many havelis in Nathadwara, Kankroli, Mumbai and Vadodara for the past 20 years. From 2006 to 2008 he visited Singapore to illustrate paintings for the Shree Yamunashtak Granth commissioned by Dwarkeshlalji, Goswami of Kalyanrayji haveli, Vadodara.

Usha Soni: Trained under Harishchandra Swarnakar, practising this art for past 12 years. Involved in the decoration of Shrinathji idol, seva and aarti preparation.

Rajesh Tailang: Has an M.A. (Drawing and Painting) from Nathadwara College, Mohandas Sukhadia University, Udaipur. Besides being an accomplished portrait painter and flute player, Tailang paints Pichhwai, Krishna Leela and Manoratha.

Harikant Harnarayan Sharma (49 years old): Trained under his father, the late Harnarayanji, a legendary painter of Nathadwara. He has been painting pichhwais, murals and Krishna Leela paintings for 35 years.

Vishnu Harnarayan Sharma (41 years old): Vishnu is also the son and disciple of the late Harnarayanji. He paints pichhwais, murals and Krishna Leela paintings. Both Harikant and Vishnu conduct workshops for young enthusiasts in their studio. They also follow their family tradition of temple painting seva.

Krishnakant Maneklalji Sharma (uncle of Harikant and Vishnu, 55 years old): Krishnakant trained under his father the late Maneklalji (also a legendary painter) and uncle Harnarayanji. Maneklalji runs an institution called ‘Nathadwara School’ and has trained many artists, he has also worked with Indra Sharma and B.G. Sharma. He has been painting pichhwais, murals and Krishna Leela paintings for 40 years.

Raghunandanji Harnarayan Sharma (55 years old): Raghunandanji was trained under his father the late Harnarayanji, and has been painting pichhwais, Manoratha and Krishna Leela paintings for 35 years.

Murlidhar Sharma (60 years old): Murlidhar was trained under his father. His Ajanta Art is among very few shops where Shrinathji idol paintings, pichhwais, manoratha and Krishna Leela paintings are prepared according to the demand of the connoisseurs and devotees.

Note: The present text is based on conversations with practising artists and some observations during fieldwork.

Further Reading

Ambalal, Amit. 1987. Krishna as Shrinathji: Rajasthani Paintings from Nathadvara. Ahmedabad: Mapin Publication.

Kanitkar, R.P. 1975. Chitrashalecha Itihas 1878–1973 (Marathi). Pune.

Pinney, Christopher. 2004. Photos of the Gods: The Printed Image and Political Struggle in India. London: Reaktion Books.

Skelton, Robert. 1973. Rajasthani Temple Hangings of the Krishna Cult. New York: American Federation of Arts.

Murlidhar Sharma, Chappan Bhog manorath pichhvai with various darshanas (2009)

Harishchandra Swarnakar, Krishna Leela painting, undercoat, 2014

Right side: Icon images, wooden cut-outs for souvenir making in the studio, Harishchandra Swarnakar, Kankroli. Left side: Diamond studded and embellished wooden cut-outs of Srinathji icon with painted background

Vishnu Harnarayan Sharma in his studio with his recent Krishna Leela painting

Harikant Harnarayan Sharma in his studio, Chitrakaron ki gali, Nathadwara. Left: Rasleela pichhvai by Harnarayan and Harikant Sharma

Ajanta Art, a shop of handmade pichhvais, souvenirs and popular decorative items at nathadwara

Studio of Harishchandra Swarnakar at Kankroli. From right to left: artists Usha Soni, Harishchandra Swarnakar (holding the book Yamunashtakam illustrated by him), Rajesh Tailang (last seated).

Photographs by Prakash Lokhande