A book authoured by Dr Horst Metzger, the distinguished collector of Indian art, and Maharao Brijraj Singh of Kota gives an insight into life in the Kota kingdom from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries through paintings, writes Prof. B.N. Goswamy. (Photo courtesy: LA County Museum/Wikimedia Commons)

This article appeared originally in The Tribune, Chandigarh under the title 'The Persistence of Memory' and is reproduced here with permission.

"To all the customs (of the Rajputs), to all their sympathies, and numerous acts of courtesy and kindness, which have made this (Rajasthan) not a strange land to me, I am about to bid farewell; whether a final one, is written in that book, which for wise purposes is sealed to mortal vision: but wherever I go, whatever days I may number, nor place, nor time, can ever weaken, far less obliterate, the remembrance of these . . ."— Col. James Tod, Personal Narrative, 1820, in Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan.

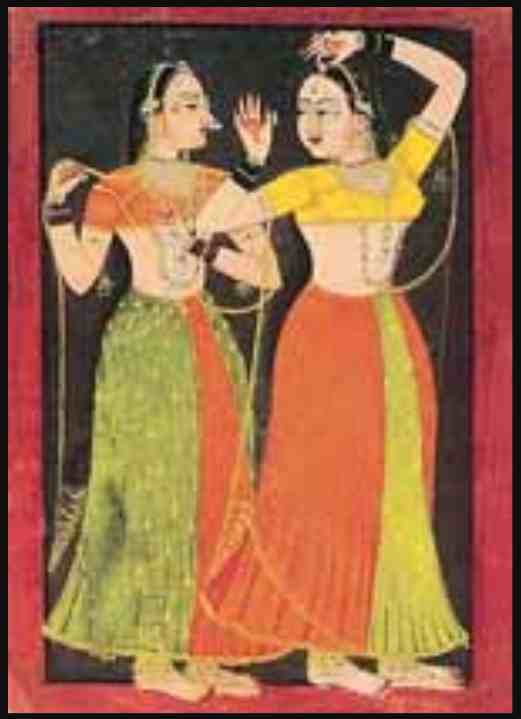

If one were to pick up, today, any book on Kota, that proud kingdom once ruled by the Haras of Rajasthan, it is almost certain that it would be devoted to the great paintings of that state. Within its covers, one would be apt to see, through the eyes of its painters, the eerie majesty of those rocky landscapes in which tigers lurk behind incomparably lush foliage; nayikas casting sly, last-minute glances at themselves in mirrors set into thumb-rings; the sun-bird Garuda winging his way through the air, bearing the great God, Vishnu, on his back; lovers gazing at monsoon clouds, seated on marble terraces; rulers moving through crowded bazaars, astride magnificently caparisoned elephants with lissome dancers balancing themselves on their tusks.

Also read | Nathdwara Paintings: Shrinathji Cult, Haveli Traditions and Bazaars

The most recent book on Kota that has come to my notice, however, sees that state with altogether different eyes. Authored by Horst Metzger, the distinguished collector of Indian art, and Maharao Brijraj Singh of Kotah—and published, with the usual elegance, by the Museum Rietberg, Zurich—the book has as its canvas the Festivals and Ceremonies as observed by the Royal Family of Kota. The idea of producing such a book seems to have come up at the time that the Museum held an exhibition of Kota paintings some three years ago: for, supporting the art of the state were shown a number of blow-ups of photographs, now included in this book. While not forming, formally, a part of the exhibition, these photographs, taken by Dr. Metzger over several years, could be seen then as somehow complementing the show, for in them was recorded, with a sense of warmth and intimacy, life as it continues to be lived by members of the royal family of Kota. One could sense through them the presence of a remarkable respect for tradition, feel the texture of the relationship between rulers and their ishta deity, understand the manner in which the public and private lives of former rulers moved in and out of each other. It was as if a new perspective had been added to old paintings.

Now, with the publication of this book, one has a chance to savour these photographs (together with many others), and the intimate view they present of life in Kota, all over again. The world that one sees reflected in them is peopled with characters of all description, much as the colourful world of paintings was: rulers and princes and courtiers, priests and preceptors, mahouts and grooms, musicians and dancing girls, morchhal-bearers and foot-soldiers. One sees members of the royal family seated in shrines decorated much as they were 200 years ago, offering worship to sacred weapons, ride in formal procession, mingling with the crowds as the celebrations of Dasehra progress from day to succeeding day, faces peering eagerly down from balconies. These photographs have, of course, the advantage of affording views of women members of the royal household—persons whom one never saw in paintings except in an idealised, near-abstracted form—but there are scenes here that come astonishingly close to those that the painters of old recorded in their own fashion. When one looks, in a relatively recent photograph, at a royal figure on an elephant drowned in a virtual sea of men, and then at a procession of the 19th century Maharao, Ram Singh II, riding on elephant back in state, the sensation one gets is of centuries being telescoped, whittled down.

Again, there is not much distance that separates Maharao Brijraj Singh standing before the image of Brijnathji today, and Maharao Kishore Singh, his ancestor at a remove of nearly 200 years, in attendance as a humble devotee before Shrinathji. It is as if, miraculously, time and space had been vacuumed out of the situation. The past and the present form—to use a photographic image—as a double exposure, as it were.

Also see | Photo Essay on Arna Jharna: The Desert Museum

The rich visuals apart, the text is shot through with insights that enhance one’s understanding of the way things were, and are. Almost as a narrative device, public festivals are closely followed over a calendar year, and then the private samskaras within the family are taken up, each rich in detail, and each sought to be placed within the passage of events that make up a life: from namakarana and upanayana to vivaha and antyeshti. But the treatment is not dull, nor merely documentary. And scattered throughout the text are little episodes, vignettes that delight and move. My favourite is the story of how the little gold image of the family deity, Brijnathji, that Maharao Bhim Singh used to carry on his person everywhere, was lost when the Maharao was killed on the battlefield, fighting against Deccani forces in 1720. Four years later, however, news of the image being safe trickled in: the Nizam had recovered the image and handed it over for safekeeping, and puja, to a Hindu merchant within his own dominions. This learnt, the Maharao’s son and successor, the redoubtable Durjan Sal, sent a deputation of Kotah sardars and officials to the Deccan. And when, with the full concurrence of the Nizam, the idol was handed over to the party for being brought back to Kota, the Maharao travelled a full fifty miles from his capital city to receive with all the State honours, and great rejoicing, the revered image. It is as if fortune were returning to a land rendered desolate by the earlier loss.

Recording History

It is certain that, in our land, history lives in many ways. One can find it in monuments; one sees it in the form of chronicles and documents. But, sometimes, it lives in the shape of a person, like Maharao Brijraj Singh of Kota whom one knows to be completely steeped in the traditions of his ancestors and his land. But this history also needs to be recorded. And, in this book, Horst Metzger’s lens has done precisely that.

This article has been republished as part of an ongoing series Art N Soul from The Tribune.