The Mughal emperor Akbar was not only interested in Christianity but also commissioned Father Jerome Xavier—a Jesuit Father at the Mughal court—to write about the life of Christ. The manuscript he produced came to be known as Mir’at al-Quds (The Mirror of Holiness) and was even translated into Latin. Prof B.N. Goswamy discusses how illustrations based on the manuscript were ‘Mughalised’ in Akbar’s court. (Photo Courtesy: The Tribune)

This article appeared originally in The Tribune, Chandigarh, and is reproduced here with permission.

After Easter, the (Jesuit) Fathers moved from their inn, which was crowded and inconvenient, to the house which the King (Akbar) had offered them in the precincts of the palace. When the King heard of their arrival he came alone to their house, and proceeded straight to the chapel, where (having laid aside his turban and shaken out his long hair) he prostrated himself on the ground in adoration of the Christ and his Mother. He then began to talk about divine things. A week later he brought three of his sons and several nobles to the see the chapel. He himself and all the others took off their shoes before entering. He told his sons to do reverence to the pictures of Christ and his Virgin Mother. One of the nobles exclaimed with emotion that she who was sitting on her throne in such beautiful garments and ornaments was in truth the Queen of Heaven. The King himself accepted with the greatest delight a very beautiful picture of the Virgin, which had been brought from Rome and was presented to him by the Fathers in the name of the Superior of the Province.

— From The Commentary of Father Monserrate on His Journey to the Court of Akbar

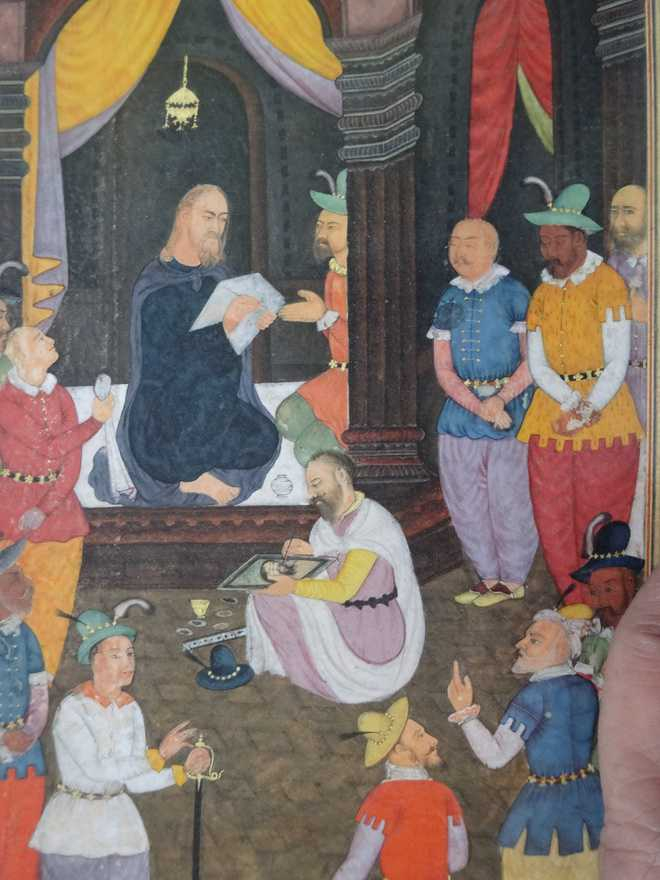

The painters who illustrated the text, basing their renderings on some European works, were constantly 'Mughalising' the work, introducing features and conventions that they felt comfortable with (Courtesy: The Tribune)

One knows all too well about the Jesuit missions to the court of emperor Akbar, and of that great emperor’s personal interest in learning about Christianity—a faith completely different from his own—and in the rendering of Christian themes in European art. The passage cited above, obviously from a Jesuit source, might not be accurate in every detail, but there can be little doubt about Akbar’s reverence for the faith concerning which he kept asking probing questions from the learned Jesuit Fathers at his court: 'We want to know the Truth on the Book of Celestial Jesus’s Law', the emperor pronounced in an Imperial edict, at one time. Nor can there be any doubt about the absorbing interest of his successor—the emperor Jahangir—in European art in which Christian themes featured so prominently: witness all those paintings of the Virgin and the Christ that hang above him, so close to his throne, in Mughal court scenes, or the works that the English ambassador, Sir Thomas Roe, kept bringing to him year after year as gifts. All this, as I said, is reasonably well known. But one knows little perhaps of a manuscript on the Life of Christ that Akbar personally commissioned a Jesuit Father to write for him in Persian. Mir’at al-Quds—'The Mirror of Holiness’—is how the work, which was submitted to the emperor in 1602, was titled, and its author was the erudite Father Jerome Xavier, who headed the third Jesuit mission to the Mughal court.

Amazingly, this text came to attract the attention of a great many people, not the emperor alone. In Mughal India, it was copied several times over; in Europe, too, it came to be well known, essentially through its translation into Latin by a Protestant minister, de Dieu—who was critical of it, being opposed to the Jesuit way—a few decades after it was written. In any case, as Pedro Moura Carvalho notes in his essay in that rich volume on 'Mughal Paintings: Art and Stories', which the Cleveland Museum of Art brought out a little over a year ago, a total of 19 copies of the Jesuit missionary’s text are now traceable. Of these, only three carry any illustrations: the Cleveland Museum acquired, in 2005, the one that was the richest, so to speak, carrying as it did as many as 27 illustrations. The manuscript, written in beautiful nastaliq characters, does not carry a date, but has been ascribed to the years between 1602 and 1604, when the emperor Akbar was in his last, declining years, and his son, Jahangir—then Prince Salim—had set up court at Allahabad.

There are renditions of the Virgin where she is wearing a bindiya (dot) on her forehead (Courtesy: The Tribune)

The manuscript is of uncommon interest, both on account of the text it contains, and of the paintings that feature in it, ‘illustrating’ episodes from the revered narrative. For, in different hands it got different tilts. There entered, as Pedro Carvalho carefully notes, some ‘idiosyncrasies’, as he calls them, in Father Jerome Xavier’s account of the Life of Jesus. The learned Jesuit introduced (evidently in order to make the story fuller, and thus of greater interest to his reader/patron, the Emperor) some episodes in his text—written originally in Portuguese and rendered in Persian with local help—that came from contentious sources, or were taken from apocryphal accounts which ‘presented certain fanciful stories as genuine’. At the same time, the painters who illustrated the text, basing their renderings on some European works, were constantly 'Mughalising' the work, introducing features and conventions that they felt comfortable with, in their own environment. The mountains in their work remain firmly Persian; the common folk all wear Indian dresses; the architecture frequently features Mughal details; the noblemen look like Mughal princes. When we see the three Magi, riding camels and heading towards the sacred site of Nativity, we see them all not as some kingly Oriental types, as they appear in countless European renderings, but as three contemporary Portuguese gentlemen, wearing those typical hats and doublets and hoses which the painters must have seen so often around themselves. Things like these are of a piece with the renderings of the Virgin in some other Mughal hands in which she appears wearing a bindiya-dot on her forehead and where her fingers are dyed in henna, as if she were some high-born, affluent Hindu lady looking down with lotus eyes at the baby in her lap.

With all this, however, possibly because of all this, it is not easy to take one’s eyes off these images. They are truly fascinating. For so much more is reflected in this ‘Mirror of Holiness’ than the sacred narrative of an Exalted Life.

This article has been republished as part of an ongoing series Art N Soul from The Tribune.