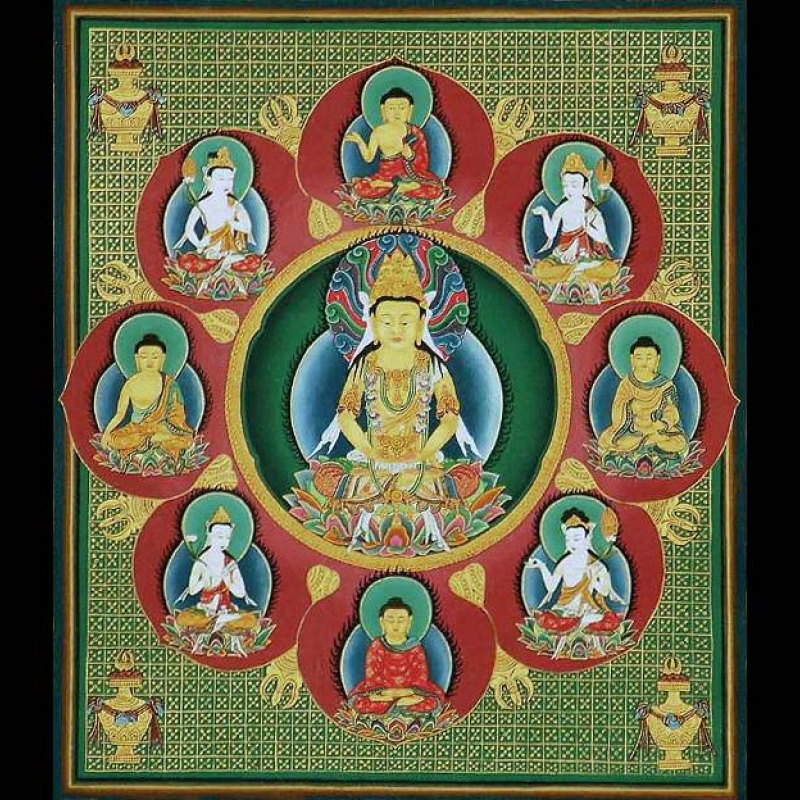

Vajrayana—the ‘Diamond Path’—the most commonly practised form of Buddhism in the Himalayan region is essentially esoteric and very hard for anyone from the outside to access. The range and the variety of images alone are staggering, writes Prof. B.N. Goswamy. Colour, direction, stance, weapons, attributes, seat, numbers: everything makes it more complex but also carries a meaning. (Photo courtesy: Wikimedia Commons)

This article appeared originally in The Tribune, Chandigarh, published under the title ‘Himalayan Buddhism’ and is reproduced here with permission.

Buddhists are always talking about tools to use on the path to liberation. Often we are accused of living in our heads, of being too abstract. Buddhist art—and more specifically, tantric art—gives us the opportunity to come down to earth and look at how Buddhism represents itself visually. Deities in the tantric system don’t exist as external entities. They’re expressions of Buddhahood, they are emanations of a particular Buddhist teaching. These deities are peaceful, fearsome, and wrathful; they’re multi-headed and multi-armed, each one suited to the temperament of an individual tantric practitioner . . . the images are mnemonic devices. — Jeff Watt, Director of Himalayan Art Resources

Time was when I knew absolutely nothing (I still do not, to put it plainly) about what is generally referred to as Tibetan Buddhism—the more correct way to refer to it perhaps is ‘Himalayan Buddhism’, since that term covers areas well beyond Tibet, such as Nepal and Bhutan and Kashmir—but I was greatly intrigued by it. When, long ago, I was teaching at the University of Pennsylvania, therefore, I decided to take a group of my students to Baltimore, not too far from Philadelphia, to visit John and Berthe Ford, whom I had had the pleasure of meeting at a conference, and whom I knew to be distinguished collectors of Tibetan art. John and Berthe were most gracious as hosts and took us around their elegant home, room after room—gallery after gallery, really—filled with works of art. There was so much to see but what simply took our breath away was their private shrine at the heart of which stood an exquisite bronze: an image of, if I recall correctly, Avalokiteshwara. The memory of it still lingers in some corner of my mind.

Related | Guru Padmasambhava: Symbolism and Visual Culture

Several years later, I entered the world of Himalayan Buddhism again, although strictly still as an outsider. This was when a dear friend and colleague, Caron Smith, took over as Deputy Director of the now famed Rubin Museum of Art in New York. From her I started hearing of the treasures that the founder of the museum, Donald Rubin—a man of business in New York—had been garnering and how rich and generous was the website devoted to Tibetan art that he had launched. Donald and his wife, Shelley, had decided that “it was time to make more of this richly detailed and largely sacred art” than most people possibly could. Internet was the route to take and what they created was an ever-growing website of encyclopaedic scope in which, at last count, some 20,000 objects—sculptures, paintings, ritual objects, textiles—drawn from more than eighty collections are featured. It is a rich resource, made all the more remarkable by the fact that on it works are not only reproduced but also described and explained: one by one, detail by detail. It was as if there was a sense of mission in the enterprise. And in carrying out this mission, great help apparently came in the form of Jeff Watt who looked after the Himalayan collection in the Museum as its Curator, set up the website almost as a virtual museum of Himalayan art, and later struck out on his own to establish the Himalayan Art Resources (www.himalayanart.org). As many as 60,000 objects, one understands, have been catalogued, and the list is still growing.

Watt, who is a practising Buddhist, and spent many years learning from great masters in Buddhist retreats, has been keen on bringing the essence of Himalayan art within the reach of people who know nothing about it, and this by explaining things as simply as possible. Take this example in which he speaks of the image of Chakrasamvara. “This is a tantric meditational deity”, he says: “everything you see here is a mnemonic device. The deity’s four faces are the four brahmaviharas: loving kindness, compassion, joy, equanimity. The twelve arms represent the twelve links of causation and dependent origination. The skulls on the crown are the five aggregates of the human condition; the five jewels are transforming the aggregates into the five wisdom’s. And so on . . . All the Buddha’s teachings are compacted into this form . . . ”

Also see | Life and Teachings of Guru Padmasambhava

Vajrayana—the ‘Diamond Path’—the most commonly practised form of Buddhism in these parts is essentially esoteric and very hard for anyone from the outside to access. The range and the variety of images alone are staggering. Colour, direction, stance, weapons, attributes, seat, numbers: everything makes it more complex but also carries a meaning. Consider this, for instance: there are four basic colours that can form the ground of an image; thus, black, gold, yellow, and red. Figures can be peaceful, powerful, or wrathful; the five Buddha families—Vairochana, Akshobhya, Amitabha, Ratnasambhava, Amoghasiddhi—occupy different directions; among the yellow male deities Ganapati stands for removal of obstacles; Maitreya and Manjushri for wisdom, Ratnasambhava and Jambhala for wealth, Vajrasattva for purification, Vaishravana for protection; among the yellow female deities Bhrikuti and Marichi remove obstacles, Paranaeshwari prevents sickness, Vasudhara brings wealth, Tara leads towards liberation. In respect of hierarchy after the Guru who stands at the very top, the pinnacle, come the Buddha, the Ishtadevata, the Bodhisattva, the Arhat, the Daka/Dakini, the Protector Deity, the Wealth Deity, the four Guardian Kings. And so on. As one can see, left to oneself, one can get completely lost in all this.

Also read | The Impact of Padmasambhava’s Charismatic Teachings on Ladakhi Society and Way of Life

What is needed, and that is where even brief texts, like those in the Himalayan Art Resources catalogues, can help, is to gently enter the subject as it were, explore it. When one sees a gilt bronze figure of the eleven-headed Avalokiteshvara, for instance, one needs to know first that in Buddhism, the Bodhisattva is a being who “postpones his or her own liberation for the sake of ushering others along the path to enlightenment”. Then one is close to comprehending that this Bodhisattva has a tower of eleven heads “so that he can see panoramically those who need help” and whose suffering needs to be alleviated; his two arms multiply so that he can reach out in all directions. There are subtleties here, and great depth of meaning.

But one needs, at the same time, to keep in mind that this is just the beginning.

This article has been republished as part of an ongoing series Art N Soul from The Tribune.