During a trip to Kolkata, Prof B.N. Goswamy visited the Gurusaday Dutt Museum, with its overwhelming collection of folk art in everyday use. Of special interest to him were the various Kantha textiles, he writes. (Photo courtesy: Gurusaday Museum)

This article appeared originally in The Tribune, Chandigarh under the title 'Arts and the Common Man' and is reproduced here with permission.

It may not be widely known in our part of the country, but in Bengal, especially in Calcutta where I was just a few days ago, Gurusaday Dutt is a name that has a resonance. A member of the Indian Civil Service, Dutt seems to have been an unusual man. Quite unlike the dyed-in-the-wool brown sahibs who belonged to that elite corps, he seems to have had a passion for rural India and, as a district magistrate posted in various regions of the then province, he kept collecting objects that were a part of peoples’ daily lives. To the ordinary folk for whom sahibs of this variety were like demi-gods cast in the white man’s mould, all this might have appeared a somewhat eccentric activity, but building a collection of the kind that he did could not have been difficult. There was little value that people then had for these objects, most of which were not even meant for sale. But he must have bought many things; others might have been presented to him by ‘subjects’ all too anxious to please; still others he must certainly have saved from neglect and decay, picking them up from forsaken corners. I do not know whether, in his private life, he surrounded himself—like others of his rank—with European bric-a-brac, in imitation of fair-skinned masters; but, by the time he died in 1941, he had an imposing collection of ‘folk’ artifacts, all related to ordinary lives, all sprung from the soil. This he gave away to an organisation called the Bengal Bratachari Society. Today, the collection is housed in a museum bearing, appropriately, Gurusaday Dutt’s name. It is in this museum that I was a few days ago, as I said.

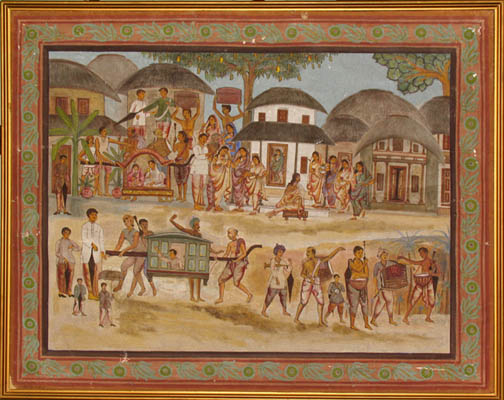

The size of the collection is overwhelming, upwards of two and a half thousand objects: Kalighat paintings, patuas’ scrolls, embroidered kanthas, terracotta panels, stone sculptures, wooden carvings, dolls and toys, moulds used for making patterns on sweets or mango-paste, and the like. One can dwell on all of these in detail – and I am certainly tempted to return at least to the first two (although at another time) – but even from the quick general impression one forms, one gets the sensation of being surrounded by the past, of feeling the texture of life as it was lived in all its ‘ordinariness’ and its comforting warmth. Here, along the walls, and in glass cases, young maidens sit preening in front of mirrors on Kalighat pats, souls of departed men rise to the higher regions or sink below in painted scrolls, deer prance about in terracotta panels and devout women go about watering tulsi plants, barbers ply their trade and hawkers move about in the form of wooden figures. It may be a world that is fast fading, but one can still reach out and touch it through this wonderful range of objects.

Related | Kapdagondas: Embroidery and Work for Dongariya Kondh Women

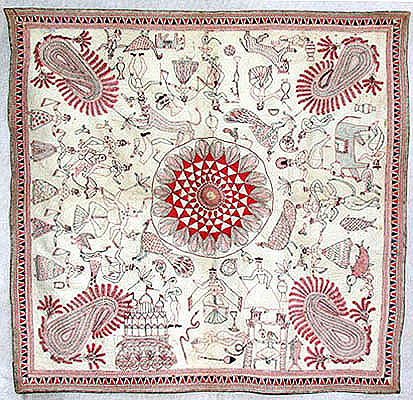

Clearly, not everything in the collection is on view, and much has been kept in reserve. But, from among what one can see, the most seductive perhaps is the large group of kanthas that belong to the collection. Just in case one does not know what these are, kanthas are essentially embroidered coverlets and wraps, traditionally made by women from discarded cotton materials and strictly for use within the family. Originally—one can see changes creep in with time—these consisted of white cotton fabric of old saris and dhotis, which were first pieced together to form the ground, several layers being used to make the required thickness. On these, patiently—and truly skillfully, sometimes—embroidery was done with coloured threads painstakingly unpicked from the borders of worn-out or discarded saris.

Making kanthas was a wonderful way of recycling old materials and putting them to totally different, innovative use. There is a touching simplicity, and artlessness, about the idea. Women would make them strictly for members of their own families: a daughter making a quilt-like wrap—called a ‘lep’—for her father, for instance; a wife preparing a bedspread—called a ‘sujani’—for her husband; a young girl designing a soft toilet-case—an ‘arshilata’—for her sister’s use, and so on. The amount of work done on different kanthas, and the level of skills commanded by different women, naturally varied. But some exquisite work was done, embroidered patterns ranging from the very simple and austere to the elaborately rich and complex. In the finest among the kanthas, the closely-worked stitches with which various pieces or layers of cotton material were first secured appear as finely done as the embroidery itself, the patterns made by these white on white stitches creating the sensation sometimes of grass making way for gusts of wind in lush fields. As for the embroidered patterns themselves, reminiscent as some of them are of alpana designs with lotus-like centres opening up and spreading from inside outwards, there seems to be an endless variety. There are of course similarities to be found, but no two kanthas can be said to have been exactly alike. Colours, patterns, arrangements keep changing even as men are seen roaming in the fields, elephants and tigers mingle with fish and turtles, platoon soldiers march and musicians play upon their outlandish instruments, lotuses bloom and shoots of corn throw roots while steam engines pull railway carriages in the background. One can see a cavalcade of life passing in front of one’s eyes, as it were.

Also see | Mapping Indian Textiles: Embroidery

Some of the kanthas were even ‘inscribed’, names and other information being embroidered on them. My favourite among these? A remarkably delicate one, with an elaborate border of ‘kolkas’, as was explained to me, made by a daughter for her father: the inscription gives her name and her father’s. And then adds, in her own simple words: "Should there be a fault in it, some error, please forgive me, for it is with much love that I have made it"!

Unlocking Meanings

If the reader is as puzzled by some of the terms used in the piece above as I initially was, let me try and offer some help, since I have worked some of them out. Local usage and the customarily rounded Bengali accent have obviously transformed these terms. ‘Lep’ is clearly a variant of ‘lef’, which in turn is taken from Persian ‘lihaf’, meaning a quilted blanket or coverlet; ‘sujni’ comes from Persian ‘sozani’, ‘quilting work . . . tamboured work . . . a seat of state’; ‘arshi’ is of course ‘aarsi’, a mirror; and ‘kolka’ a variant of Persian ‘kalgha’, or plume, much favoured as a motif in the grammar of Indian ornament: one sees it as often in Kashmiri shawls where people speak of it as ‘paisley’, as in Kutchi embroideries where one knows it as ‘kairi buti’.

This article has been republished as part of an ongoing series Art N Soul from The Tribune.