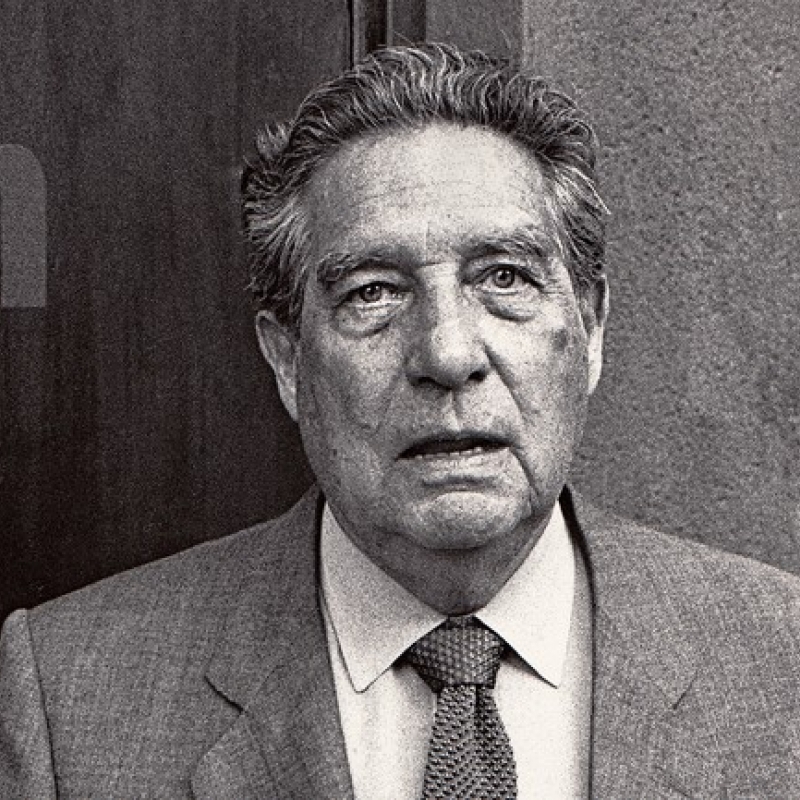

Octavio Paz's poems about Delhi are arguably the most profound and striking lines written about the city. Paz was not only a prolific poet, he was also well-read; he found Delhi's 'aesthetic equivalent' in 'novels, not in architecture'. Here, we look at Paz's verses on the Capital's architecture. (Photo Source: Jonn Leffmann/Wikimedia Commons)

The Indian subcontinent has been subject to interpretation for centuries. From the Greek explorer Megasthenes, who wrote an account of India under Chandragupta Maurya, to the American poet Allen Ginsberg, who came looking for sacred India, India and its culture have been under constant scrutiny from the West. This also includes those of Indian origin such as Trinidadian–British V.S. Naipaul, who authored a trilogy about the ‘damned people and the wretched country’, exposing their ‘detestable traits'.[i]

Paz found Delhi’s ‘aesthetic equivalent’ in ‘novels, not in architecture’ and to him, wandering the city was ‘like passing through the pages of Victor Hugo, Walter Scott, or Alexandre Dumas’ (Photo Source: Gobierno CDMX/Wikimedia Commons)

During 1962–68, when he was posted as the Mexican ambassador to India, Paz travelled across the country, collecting stories and making observations. The Nobel laureate was deeply impressed by the religious diversity and was drawn to the juxtaposition of different cultures and religions, especially in New Delhi, a city whose architecture and history went on to become recurring themes in his poetry on India.

He found Delhi’s ‘aesthetic equivalent’ in ‘novels, not in architecture’ and to him, wandering the city was ‘like passing through the pages of Victor Hugo, Walter Scott, or Alexandre Dumas'.[iii] Paz’s gaze, wherever he went, was inwards. For him, all the experiences, including the splendour of Mughal architecture that attracted him, were revelatory and enlightening in one way or the other. Within the pages of In Light of India, which talks extensively about architecture in Delhi, he wrote, while ‘Hindu architecture is sculpted dance’, in Islamic architecture ‘nothing is sculptural—exactly the opposite of the Hindu’. ‘India owes to Islam admirable works of architecture, painting, music and landscaping,’ he added.[iv]

But Delhi architecture always had a special place, which he calls ‘an assemblage of images more than buildings’. For instance, Humayun’s Tomb was ‘serene’, it was ‘a poem made not of words but of trees, pools, avenues of sand and flowers’. In his collection of poetry, A Tale of Two Gardens, 1997, he writes about the monument:

To the debate of wasps

the dialectic of monkeys

twitterings of statistics

it opposes

(high flame of rose

formed out of stone and air and birds

time in repose above the water)

silence’s architecture[v]

Interestingly, even though he was an outsider, Paz’s Delhi is as culturally rich and poignant as Charles Baudelaire’s Paris, James Joyce’s Dublin, and T.S. Eliot’s London. In his poem Balcony (A Tale of Two Gardens), reflecting on a night spent in Delhi, he wrote:

Delhi

Two tall syllables

surrounded by insomnia and sand

I say them in a low voice

Nothing moves

the hour grows

stretching out [vi]

In his poetic study, Paz not only examined the structures, but also life around them. He placed disparate images next to each other, recreating what he saw. In his poems, history and architecture are inseparable; light, silence and movement are omnipresent and add to the atmospheric serenity, and the stone walls and marble floors of the ‘vagabond architectures’ are bound to time. In The Tomb of Amir Khusrau (A Tale of Two Gardens), he wrote,

Amir Khusrau, parrot or mockingbird:

the two halves of each moment,

muddy sorrow, voice of light.

Syllables, wandering fires,

vagabond architectures:

every poem is time, and burns. [ix]

Paz was not only a prolific poet, but also well-read and well-informed. His verses have left a deep impact on India, especially Delhi (Photo Source: Royalwrote/Wikimedia Commons)

For the Mexican poet, Delhi was ‘a picturesque fusion of classical European and Indian architectures’.[x] As an observer, he not only meditated on what he saw and heard, but also deliberated on the silence offered by Delhi. He viewed the Red Fort ‘as powerful as a fort and as graceful as a palace’ and the Qutub Minar ‘a prodigious stone tree’ that was like ‘a huge rocket aimed at the stars’.[xi] At the Lodi Gardens, he witnessed the domes of mausoleums shooting birds into the sky. In the Lodi Garden (from A Tale of Two Gardens), he captured the moment with striking elegance and beauty:

The black, pensive, dense

domes of the mausoleums

suddenly shot birds

into the unanimous blue[xii]

Paz left India in 1968, but India continued to live on in the poet. According to his translator Eliot Weinberger, ‘no other Western writer has been as submerged in India as Paz’, and that ‘maybe not since Victor Segalan in China when the new century rolled over, has a Western artist been so master on, experienced in, and composed so widely about a social other’.[xiii]

During his time Paz not only influenced numerous poets, writers and artists, including Ram Kumar, Himmat Shah, Sunil Gangopadhyay, K. Satchidanandan, Krishen Khanna and J. Swaminathan, but also established long-lasting ties with them. Artist Himmat Shah said it was because of Paz that he received a government scholarship and went to Paris to study etching in 1967. Paz also got in touch with the painter Krishen Khanna, after the Mexican poet ‘discovered Khanna’s interest in poetry’ and both of them remained friends until Paz’s death in 1998. Khanna believes that even though Paz was a foreigner looking at Indian culture and architecture, his way of looking at things was very universal. According to him, Paz was not only a prolific poet but also well-read and well-informed, and whose verses have left a deep impact on India, especially Delhi.

Octavio Paz died on April 19, 1998—three years after the publication of In Light of India. The time spent in New Delhi was forever etched in his mind and its architectural magnificence left a deep impact on his works. Delhi influenced Paz and he reciprocated by writing about the city he lived in for six years, immortalizing himself in the history of the city through his poems, and—in the process—refuting Naipaul’s opinion that there was no room for outsiders in India.

A version of this article was also published in Scroll.in.

Notes

[i] Patrick French, ‘Naipaul and India’, Outlook Magazine, March 31, 2008, https://www.outlookindia.com/magazine/story/naipaul-and-india/237068.

[ii] Octavio Paz, In Light of India (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1995), 15.

[iii] Octavio Paz, In Light of India (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1995), 16.

[iv] Octavio Paz, In Light of India (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1995), 18.

[v] Octavio Paz, A Tale of Two Gardens (New York: New Directions Publishing, 1997), 32.

[vi] Octavio Paz, A Tale of Two Gardens (New York: New Directions Publishing, 1997), 23.