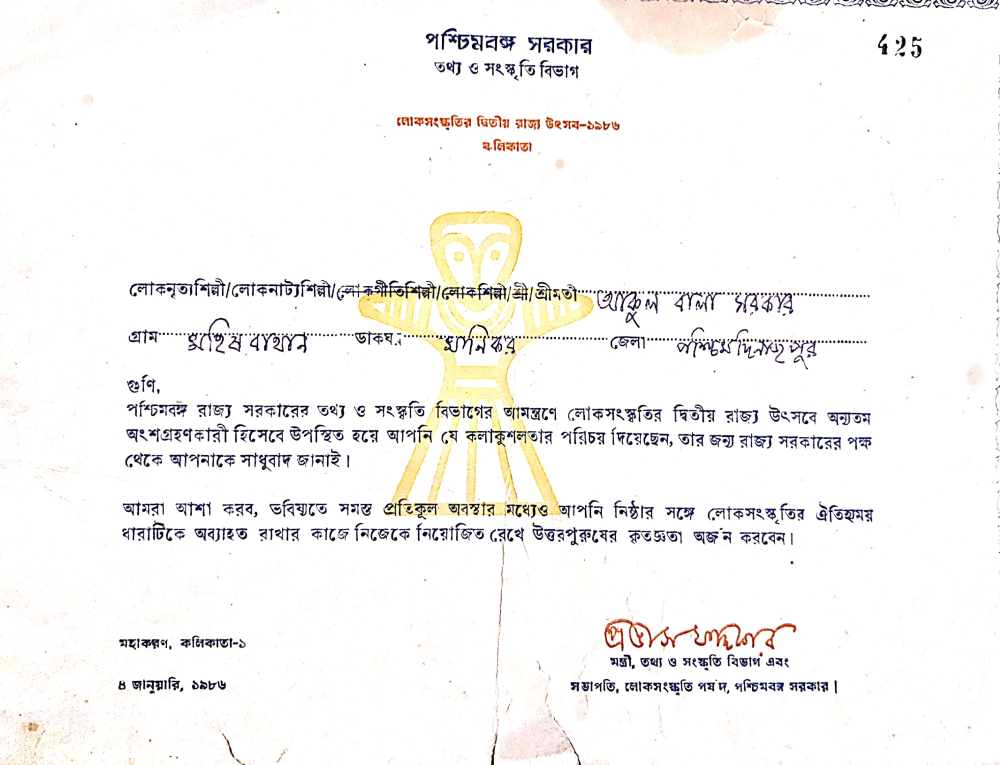

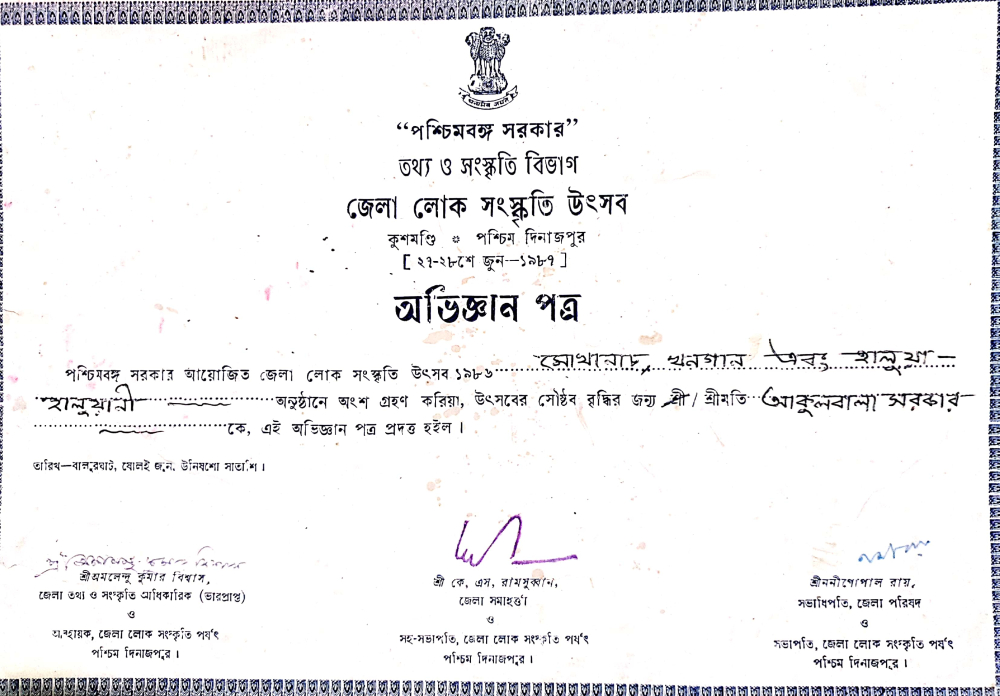

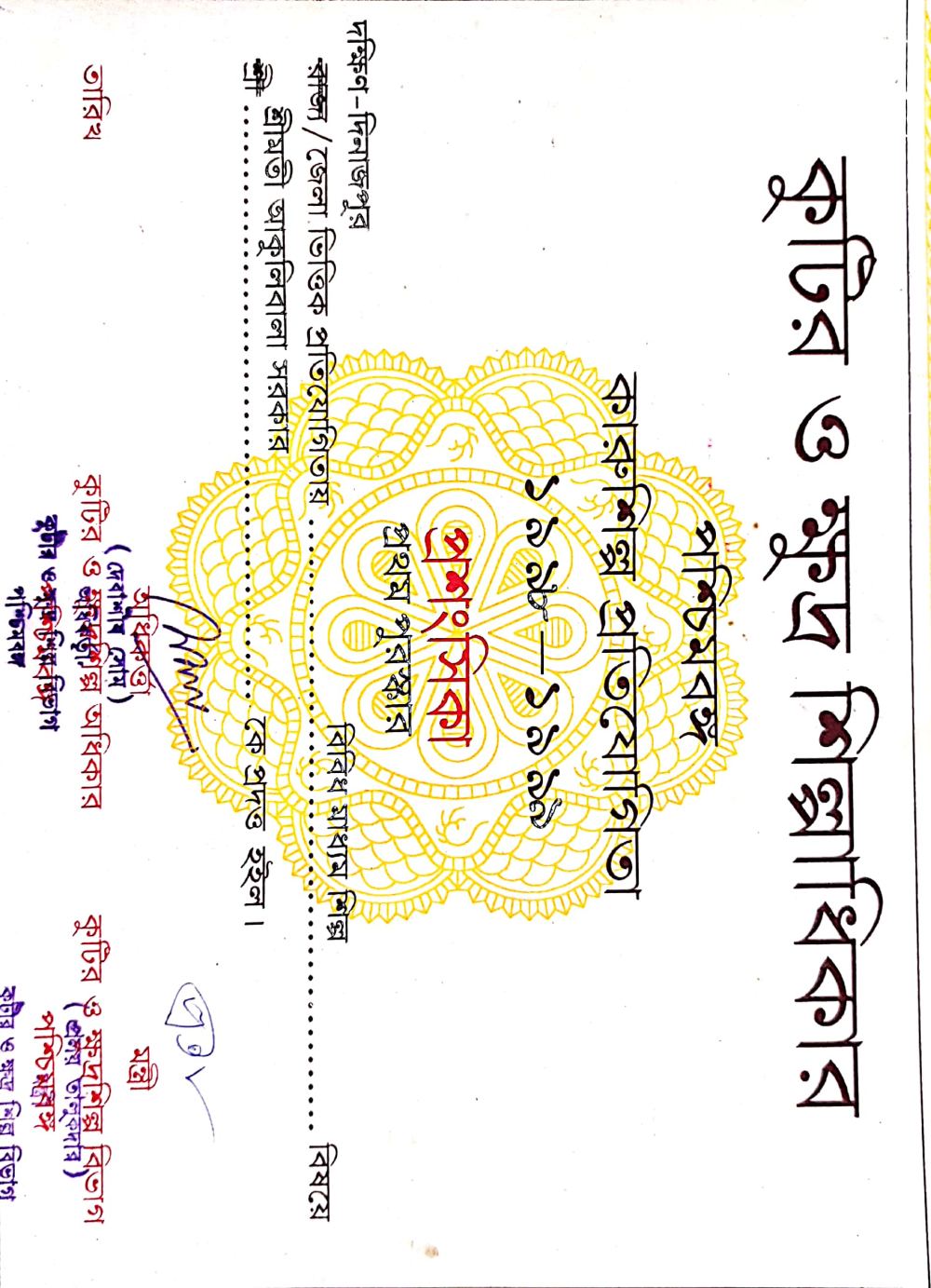

Performing in khon was always considered to be a taboo for women in a male-dominated society as it required them to move beyond the private sphere of household and engage with other khon artists in the public sphere. However, Akulbala Sarkar became a pathbreaker as the rebel woman artist who unshackled herself from this social stigma by becoming the first woman khon performer. (Fig.1) Performing as a khon artist since she was 12, Akulbala is the recipient of several awards and state-level recognition. In 1986, Akulbala was felicitated at the second Lok Sanskriti Utsav organised by the Department of Information and Cultural Affairs, Government of West Bengal. (Fig. 2). She also received a special certificate of commendation at the District Lok Sanskriti Utsav in 1987 organised by Department of Information and Cultural Affairs, Government of West Bengal. (Fig. 3), and was awarded the best performer in a performing arts competition organised by Rural Handicrafts and Micro Small and Medium Enterprises Department, Government of West Bengal in 1999. (Fig. 4) As time passed, her stature as a performer grew and, in 2010, she received the Ambedkar Award from University of Calcutta for her contribution to the field of folk drama and preserving the culture of Dakshin Dinajpur. (Fig. 5)

Against all Odds

Things though were not always as easy when a teenaged Akulbala started performing khon as lone performer in a world full of male artists who doubled up as female actors in female attires. Akulbala was at a disadvantage in more than one way; while most khon performers came from families who were practitioners of the same art form, Akulbala did not have the blessing of such lineage. Her parents completely opposed the idea of their daughter practising khon, and they ostracised her for her choice. While she championed the cause of women performers, she had to learn the art form on her own, in the process of unlearning the social prejudice by which she was expected to abide.

It was her husband, Ramani Kanta Sarkar, who mentored her informally and helped her master the art form. Ramani Kanta was initially a khon artist—primarily, a musician who used to work as a freelance performer in various khon groups—and he travelled to different places within the district. Akulbala used to accompany him, thereby getting exposed to the various nuances of khon. The couple was shunned by the neighbours and the community, but Akulbala remained undeterred: ‘Ami tao graam charini. Ami gaan korbo, khon korbo, dekhi amakey ke atkaye’ (I still did not leave the village. I will sing, I will perform khon, let’s see who stops me). (Fig. 6) She finally married Ramani Kanta Sarkar and, to this date, they are performing together. Success was hard to come by at first; however, with the passage of time, she did manage to carve out a space and name for herself. Her family eventually accepted her, which further motivated her. Those who had rejected her in the community because of being a woman khon performer, embraced her back when they saw her perform. From there, she went on to found her own khon group, Mohisbathan Naarikolyan Samiti in Kushmandi in Dakshin Dinajpur district, West Bengal, which was an all-women group, barring her husband. Her own daughter, Geeta Sarkar, is now a prominent artist in the group as is her son-in-law, Madhav Sarkar. (Fig. 7) Other women khon artists in her group are Chitra Sarkar, Geeta Sarkar, Kemota Sarkar, Jasodha Sarkar, Bheshobala Sarkar, Paheli Sarkar, and Panchami Sarkar.

Akulbala once led a poverty-stricken life and recalls instances when she had to ask for food from the neighbouring households to sustain her family. Khon was essentially a male-dominated performance and it took time to convince people that she can lead a theatre group. Khon for women has come a long way since Akulbala started:

Now I have the liberty to convince them that taking part in khon is no longer a taboo. I was the one who was ostracised back in my days but now the society is far more accepting and, at times, encouraging too. It feels good to be some sort of a torchbearer for women-led khon performances. I used to get paid four annas for every performance; but now, performers are getting government-aided pension, so you can say that the scenario has changed in our [women’s] favour over the years. My husband is the chief composer while I sing and act along with other members. The audience reaction has also changed over time.[1]

The Performer and the Stage

Her first performance was in the play Hejakshori led by ibaudiya (leader of the khon group) Bandaru Sarkar. The play chronicled the life of an inanimate object, the hajak (a kerosene lamp), and its place in the villager’s domestic affairs.

Akulbala has performed Halua Haluani twice in New Delhi, Kolkata, Jalpaiguri, Darjeeling and Siliguri. The character of halua (farmer) is played by Ramani Kanta, who is seen arguing with haluani (farmer’s wife), Akulbala, to get him his daily lunch of panta bhaat (rice soaked overnight) with a tinge of salt and ghee. Durga Boli is one of the Akulbala’s most prominent plays which she performs with her group as a part of Kojagori festival before Durga Puja. (Fig. 8) Her other famous plays are plays Pumpingshori, Buloshori, Sapuria Murder, and Police Murder (Fig. 9), the last of which once led to a real-life spectacle. Akulbala recollects a performance of Police Murder which due to a series of confusions led to the detention of the entire group by the police. As part of the script, she was enacting a scene where some people conspire to murder a police officer, which somehow reached the local thana, courtesy informers.

This led to a contingent of police personnel, including the borobabu (officer-in-charge), turning up at the venue of the performance; Akulbala and her entire team was detained. Consequently, they explained the plot to the police officers after which they were allowed to perform; this culminated into an overwhelming response from the spectators which included the police personnel themselves.

Ankubla and the Evolution of Khon

Akulbala Sarkar looks back at the time when she started out which also gives us a picture of khon’s performance scene then:

It feels great when I get acknowledged in my state as well as in other cities of the country. But it did not come without a price. The journey has been a difficult one. Hopefully, the story of an unheralded woman from a remote village to come all this way will inspire others to unshackle themselves from the societal norms and moral barriers. More than the love and passion for my art, I did not stop chasing my dream. Over the years, the disdain and neglect turned to respect. Isn’t that what all performers carve for? [2]

Over the years, the khon’s form has evolved along with an evolving audience who have been open to among other things the inclusion of women performers:

I have earned my place as a first among equals. Gender should never be a hurdle for an artist to excel in performing arts. My heart soars with content gratification when I see so many women khon performers today. The audience, too, have undergone a transformative reorientation, in their benign acceptance, in turn, overhauling the society at large, making it more conducive for more women performers to grace the folk-art form of khon.[3]

Akulbala argues that khon has slowly developed a relationship with monetary remuneration that acts as a major catalyst for bringing about a social change in the lives of the khon artists. Earlier, for the performer, khon was always a secondary means of livelihood, all of them were agricultural labourers first. But now, with more exposure and performances in cities along with a steady source of income via monthly pension, their financial condition has received a tremendous boost. The artists now receive a bhata (monetary compensation) that has made the performance way more economically viable and socially acceptable; Akulbala herself gets INR 1,000 in bhata and has been enrolled by the West Bengal state government as a registered folk artist.

She mentions that when she started performing, the khon performances were a major source of entertainment and used to be enacted at different festivals during the night. The concept of stage was not prevalent, and the performances used to take place in a circular area. The performance space of khon comprises three circles: the innermost circle is called dohar where the musical instruments are placed, and the performers play these instruments; the middle circle is where the performers act out their dialogues; and the outer circle is where the audience surrounds these performers. This circular shape of the performing space symbolises a form of socialist pattern of community living where people do not have any form of hierarchy and they sit together, and everybody has the same access to the performing space.

The performers before starting the performance worship the various deities. At present, Khon performances take place throughout the year, but traditionally khon forms an important element of Chaitra Parva (Spring Festival) in the month of Chaitra and Baishak (March/ April). Khon performance is entirely a community-based performance where the artists collect chanda (collection of money from people in the community) and procure the essential performing tools, props, and kits (lipstick, false hair, face powder, costume, etc.). With the advent of governmental intervention, the idea of having a stage is gaining popularity. Khon, Akulbala says, has also evolved over time in terms of props and presentation like the use of masks which is a trend in khon performances these days.

Akulbala’s target audience, now, in the rural areas of Dinajpur are from the Rajbanshi community and, therefore, she caters to their expectations by penning dialogues as well as composing songs in the local Rajbanshi dialect. However, when she travels to Kolkata or any other city outside West Bengal, her performance is dominated by mainstream colloquial Bengali, and even the duration of her performances is curtailed to a convenient one-hour time bracket. She has also worked in some government-sponsored khon performances carrying social messages such as prevention of child marriage and information about diseases, especially dengue.

When asked about her role in carrying forward the legacy of khon, she says she regularly makes the younger children of the Rajbanshi community of her village practise khon so that they can take the tradition forward.