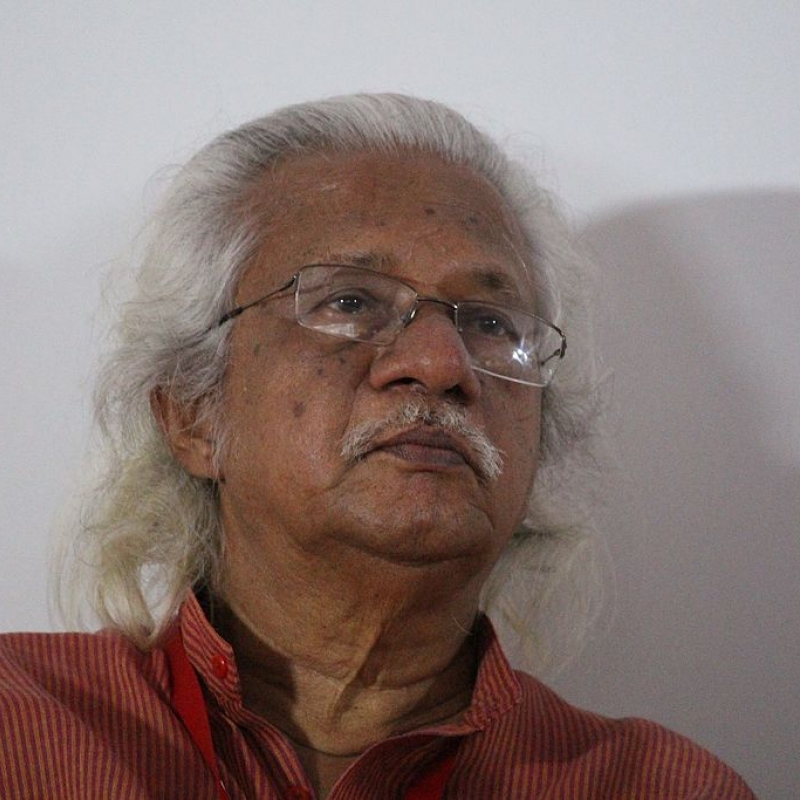

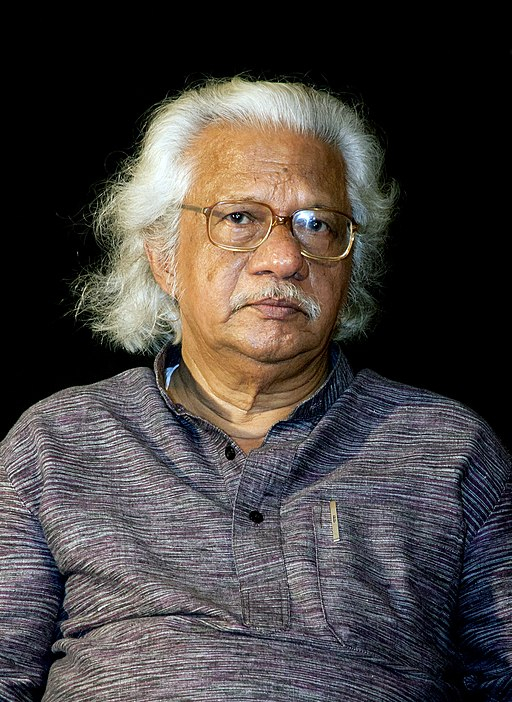

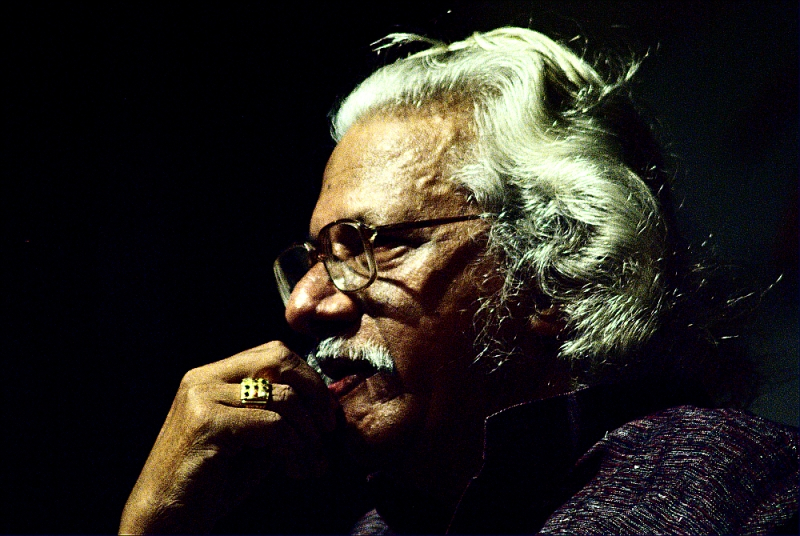

Adoor Gopalakrishnan is credited with pioneering the ‘new wave’ in Malayalam cinema in the 1960s and 1970s. We look at why he is widely hailed as the true heir to Satyajit Ray’s tradition of film-making (Photo Courtesy: Navaneeth Krishnan S [CC BY-SA 4.0])

‘I have a seen a classic in India—Elippathayam (The Rat Trap),’ said the revered Cuban film-maker, Tomás Gutiérrez Alea, at the end of his visit to India in the early 1990s. The remark left some critics in Kerala wondering if the film was an adaptation of Alea’s film, Los Sobrevivientes (The Survivors, 1979). Whether or not that was the case, the Malayalam film succeeded in earning Adoor Gopalakrishnan, its director, global recognition after the British Film Institute (BFI) called Elippathayam the ‘most original and imaginative film’ in 1982. This rare honour had only been given to one Indian before him—Satyajit Ray.

Also Read | Aravindan: A Scriptless Creative Film Director

Gopalakrishnan was no stranger to such ‘sweet accidents’. Although his first feature film, Swayamvaram (1972), originally received a lukewarm response, it was India’s official entry to the Moscow Film Festival. I.K. Gujral, the then minister of Information and Broadcasting and a connoisseur of ‘new wave’ cinema, was in the audience. Soon afterwards, Gopalakrishnan appealed to Gujral for his film to be considered for the National Film Awards. As he waited for a response, he heard a news bulletin on All India Radio stating that Swayamvaram had created history by winning in four categories at the National Film Awards (Best Film, Best Director, Best Cinematographer and Best Actress).

Gopalakrishnan's film Swayamvaram, which had previously been pulled out of cinemas for being an unprofitable venture, reopened to packed theatres across Kerala in 1973 (Courtesy: Hareesh N. Nampoothiri [CC BY-SA 4.0])

Swayamvaram, which had previously been pulled out of cinemas for being an unprofitable venture, reopened to packed theatres across Kerala in 1973. It made enough money to repay the Film Finance Corporation’s loan of Rs 1.5 lakh, becoming the first film to do so. Swayamvaram also made Malayalis realise the power of films as an aesthetic art form, similar to literature and theatre.

Through the establishment of film societies across Kerala in the 1960s and 1970s, the style of film-making advanced by Gopalakrishnan and his friends was widely accepted. In 1966 he co-founded the Chitralekha Film Cooperative (CFC), a rare experiment in alternative film-making wholly supported by the Kerala state government, and was its chairman till 1980. The CFC and its studio provided technical and production facilities to many newcomers of the time, including G. Aravindan, leading to a ‘new wave’ in Malayalam films.

Also Read | The Many Legacies of John Abraham

‘It is worth noting that innovations of Swayamvaram caught Kerala and its cinema unawares. They even went one up on the (Satyajit) Ray model of complete creative control of the film,’ wrote film scholar Chidananda Das Gupta in Seeing is Believing: Selected Writings on Cinema. This comparison with Ray’s style is fairly common in film scholarship, not only with Swayamvaram, but with Vidheyan and his later films as well.

Swayamvaram was made in the Indian neo-realist tradition of film-making, similar to Ray’s early films. Ray himself became an admirer of Gopalakrishnan after seeing his second film, Kodiyettam (Ascent), in 1978. Both had common features in their film-making style. ‘Cast in the Ray mould, Gopalakrishnan writes most of his own stories, looks through the lens to check every frame and is in every sense the auteur of his works, in control of all aspects of filmmaking. Like Ozu (Yasujiro), he emphasizes the ordinariness of the ordinary,’ observed Das Gupta. The critic also differentiated between the two, describing Gopalakrishnan’s ‘creative control of (Swayamvaram)’. He wrote, ‘But here his resemblance to the Ray-mould directors ends. The rest is Adoor. The power of silence, the quasi-Japanese sense of space, the stolidity of the steady image, the force of repetition—are all his.’

Gopalakrishnan, like Ray, has been the subject of several critical and analytical works worldwide, including an authorised biography. Till 2019, four books in English and five in Malayalam—analysing his films and life as a film-maker—have been published (Courtesy: Arayilpdas at Malayalam Wikipedia [CC BY-SA 3.0]

Gopalakrishnan, like Ray, has been the subject of several critical and analytical works worldwide, including an authorised biography. Till 2019, four books in English and five in Malayalam—analysing his films and life as a film-maker—have been published. Four documentaries on him have been made, the most notable being Images/Reflections (2015) by Kannada film-maker Girish Kasaravalli. The winner of numerous national and international awards, Gopalakrishnan has also authored six books in Malayalam. In his 54-year career, the Pune Film and Television Institute of India graduate has made 12 feature films, 26 short films and documentaries and is active even today. His short film Sukhantyam (Happy Ending) was released in 2019.

In the preface to Parthajit Baruah’s Face-to-Face: The Cinema of Adoor Gopalakrishnan, film writer Jean-Michel Frodon sums up the Dadasaheb Phalke awardee and his craft of film-making:

Visually magnificent but always in a non-self-imposing way, inventing creative use of the musical score (and of the absence of it) … Adoor’s mise en scene makes use of an extraordinarily large array of cinematic tools … In this sense, Adoor Gopalakrishnan’s films not only proclaim his own achievement, but serve as a kind of anthem for the very nature of film-making at its best.

Also Read | Satyajit Ray and His Two Powerful Female Mentors

It’s no wonder then that Gopalakrishnan, with his auteur approach and deep insight into the craft of film-making, was added to the list of the world’s most exclusive film-makers—alongside Yasujiro Ozu (Japan), Satyajit Ray and Michelangelo Antonioni (Italy)—by the conservative BFI in 1982.

Such an exclusive honour led senior critics like Vidyarthi Chatterjee to describe Gopalakrishnan as the ‘heir to [Satyajit] Ray’s tradition’ (in a 1983 article on Elippathayam in The Statesman). A similar sentiment was also expressed by film writer Gautam Kaul in The Hindu soon after Ray’s death: ‘Adoor as a film craftsman has won the respect of his colleagues and fans. [Just like Ray] most of his works have been of high calibre, enjoying a permanent shelf life.’

Gopalakrishnan, indeed, is a worthy heir to Ray in Indian films, as no other Indian film-maker’s work has been as exciting for film buffs, writers and film-makers alike, both at a national and an international level.

This article was also published in The Indian Express.