Siddis and Habshis are Indian citizens of African descent who live in the states of Gujarat, Maharashtra, Telangana and Karnataka in India. Within secondary literature, the word ‘Siddi’ can be traced to the Arabic word ‘Sayyid’, which either denotes a title and/or lineage to Prophet Muhammad.[1] ‘Habshi’, on the other hand, indicates a geographic linkage to ‘el-Habash’, the Arabic term for Abyssinia or what includes parts of present-day Ethiopia, Eritrea and Sudan.[2]

Siddi, as a category, was used to refer to Africans who, in the nineteenth century, were part of the influx of people into the port of Bombay under British imperial surveillance.[3] These communities continue to be categorised as ‘Siddi’ in contemporary official government documents such as the Indian Census. It is important to keep in mind that Siddi and Habshi are common terms that are used to refer to members of these communities but are in no way exclusive markers of their identity, in general or within India. Indeed, the usage of these names by members of these communities varies depending on the individual, as ‘Siddi’ and ‘Habshi’ can be interchangeable, vastly distinct or even entirely incorrect.

The problem of determining the proper terminology is only one aspect of producing a nuanced understanding of these communities. Another problem which arises is their amalgamation into a people united by geographic, ethnic and temporal origins.[4] Most journalistic coverage today tends to reduce Siddis to a single ‘hidden’ or ‘forgotten’ tribe which arrived in India as part of the East African slave trade. This article aims to illustrate these communities as a diverse and enduring African presence in India rather than a single homogeneous community.

Multiple African Origins

African presence in India predates the development of kingdoms, empires and the nation state. Historians such as Joseph E. Harris (1996)[5] and Shanti Sadiq Ali (1996)[6] have argued that Siddis came to India as slaves via the Indian Ocean slave trade. From the ninth century onwards, trade routes connected Eastern Africa with the Middle East and South Asia.[7] While many Siddis were either military conscripts or domestic slaves, there were also Siddis who came to the subcontinent as traders and sailors.[8] The narrative that Siddis are the descendants of slaves tends to reify the foreignness and difference of present-day communities with linkages to African peoples. It is, therefore, important to mention the very diverse and multiple African origins of the members of these communities in order to prevent their homogenisation as well as to emphasise the fact that they also share ancestral linkages with local populations in India.

It is difficult to locate sources before the thirteenth century which confirm the presence of Africans in India,[9] but it is commonly accepted that the western coast of India—the Indian Ocean littoral—has historically enjoyed trade and cultural exchanges with many parts of the world. Scholars have written that Africans were enslaved in the course of the Indian Ocean slave trade, serving as military and domestic labour.[10] During the medieval period, Africans, particularly men, gained fairly prominent roles through military conscription. During the mid-thirteenth century, in the social landscape of the Delhi Sultanate, an Abyssinian slave named Jamal-ud-Din Yakut loyally served Razia Sultan (who was her father Shams ud-Din Iltutmish’s choice as heir to the throne). Razia’s brother, Firuz, contested her assumption to the throne, launching a battle for succession.[11] Razia successfully ascended the throne, and she honoured Yakut with a position primarily reserved for Turkic (the ethnicity of the rulers of the Sultanates) nobles. He was soon killed, and Razia Sultan’s reign came to an end shortly after.

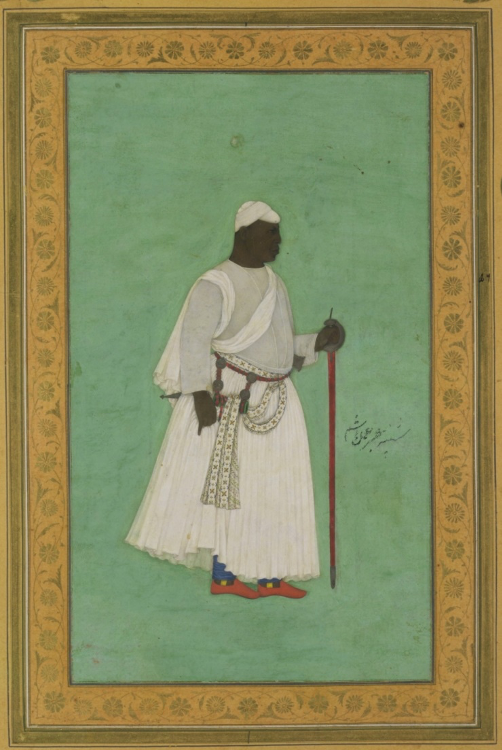

In the Deccan, Malik Ambar (1548–1626; Fig. 1) was another former slave of Abyssinian origin who left his imprint as a formidable military tactician. After gaining manumission following the death of Chingaz Khan (a free Habshi who purchased him), Ambar worked for other nobles until he assumed regency of the Nizam Shahi dynasty in the Deccan. During his lifetime, he faced many threats from Mughal armies. Historian Richard Eaton discusses how Ambar appeared in Mughal Emperor Jahangir’s memoirs as his enemy, and how Ambar’s decapitated head was also featured in a painting meant to represent Jahangir’s great ambition to venture into the Deccan.[12] Malik Ambar placed a fellow Siddi, Sidi Ambar the Little (1621–1642), as the first ruler of the nearby princely state of Janjira.[13] Siddis first came to Janjira as traders in the fifteenth century, and from 1621 until the merger of all princely states into the Indian Union in March 1948, Janjira was ruled by a Siddi family dynasty.[14]

Besides being conscripted into military service over two hundred years ago, those categorised as Siddis and Habshis came to various parts of India in search of employment, or as domestic slaves. Bombay had served as a large entrepôt in the Indian Ocean at that time, and was often the first arrival point for travellers and traders from Zanzibar, Muscat and Jeddah, a familiar route during the Indian Ocean slave trade.

Siddis were often used as domestic slaves by wealthy Arab families as well, most prominently in the princely state of Hyderabad in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.[15] Prior to the abolition of slavery by Britain in the late nineteenth century, it was an established practice that when Arabs journeyed to perform the Hajj, they would procure African slaves at informal markets in Mecca.[16] With increasing checks on slavery coming in, wealthy Arabs often disguised enslaved Siddi men as women to avoid detection while entering Hyderabad.[17] Simultaneously, during this period, Siddis also came to India of their own volition by navigating travel networks established by kinship ties with families already living on the subcontinent or who held positions in the British military.[18] A British observer in Bombay, S.M. Edwardes, noted that Siddis found employment as they ‘supply the steamship companies with stokers, firemen, and engine-room assistants, and the dockyards and workshops with fitters and mechanics.’[19] They were also employed in occupations ranging from translators and sailors to members of the ceremonial guard for the sixth and seventh Nizams of Hyderabad.

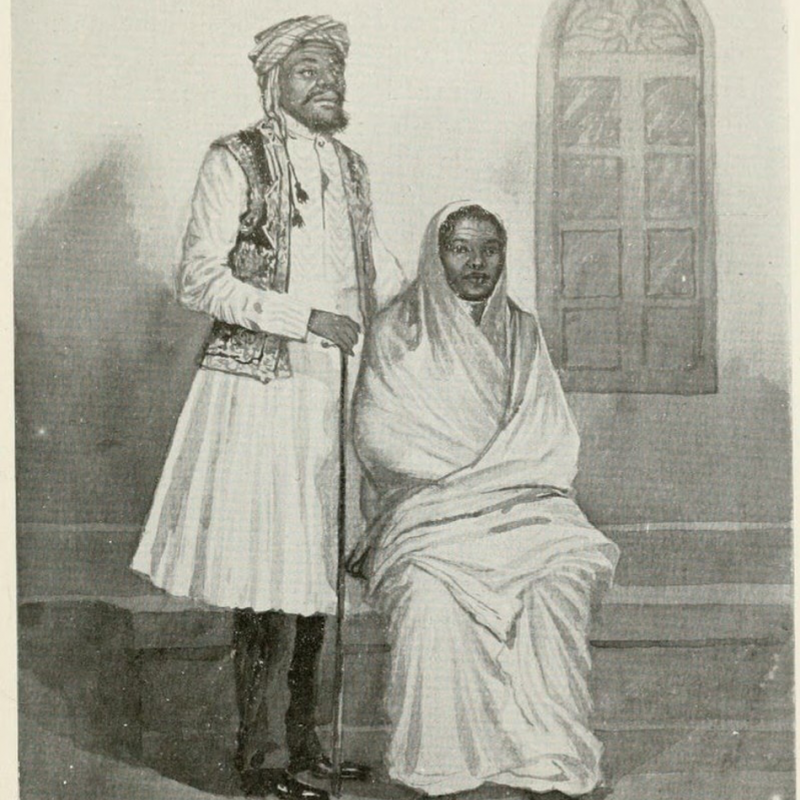

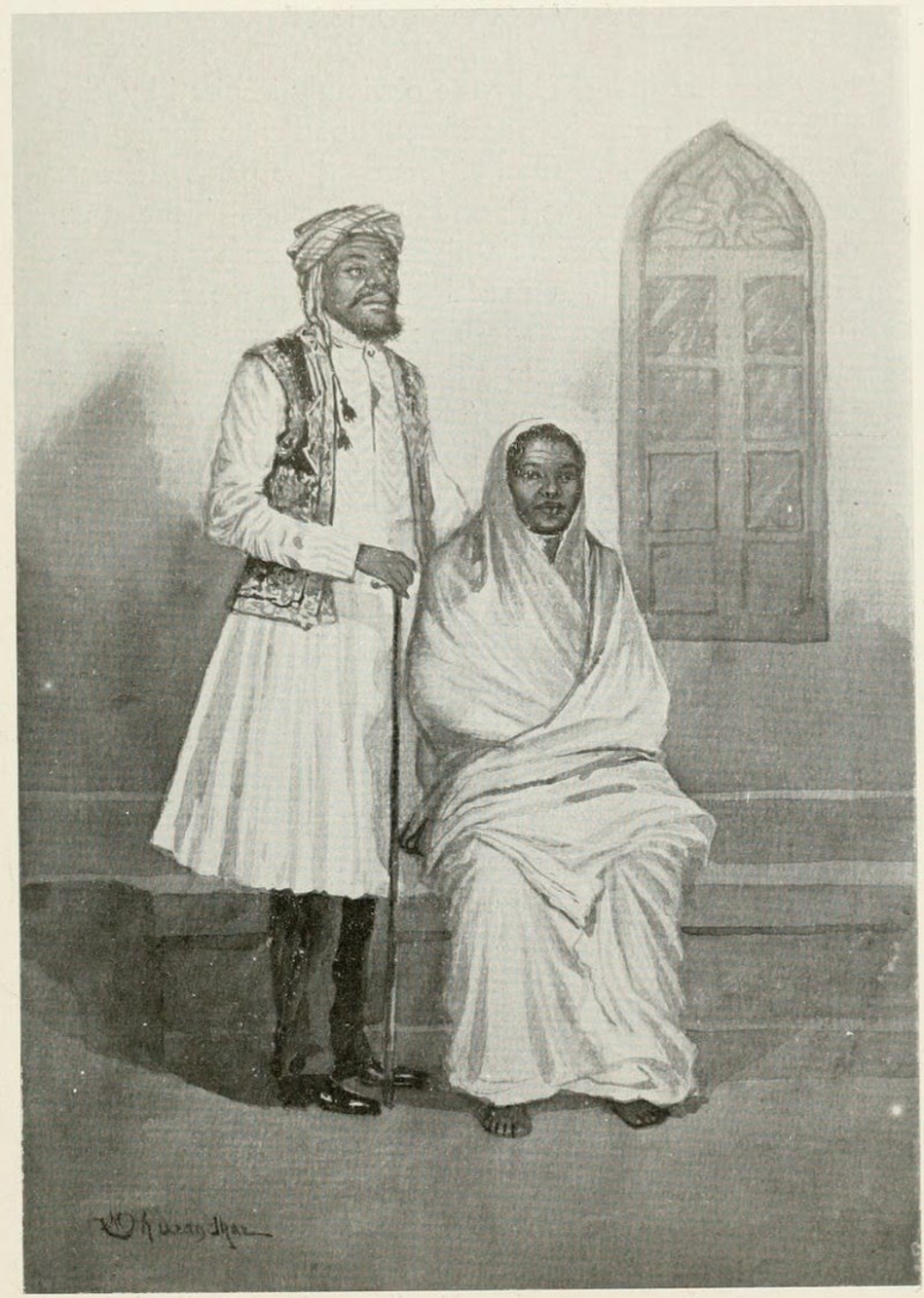

It was largely Siddi men who moved to India and formed families with local women. (Fig. 2) However, there were cases of Siddi women who married local men, as S.M. Edwardes observed:

Here and there among the faces you miss the well-known type. The thick prominent lips yield place to more delicate mouths, the shapeless nose to the slightly aquiline, for there are half-breeds here, who take more after their Indian fathers than their African mothers, and who serve as a living example of the tricks that Nature can play in the intermingling of races.[20]

Forming these families was not a rupture from the past but rather a continuation. Even during earlier periods when Siddis had gained relatively privileged high-ranking positions, they formed marriages with local women in order to cultivate advantageous political alliances.

Thus, African presence in India is the result of multiple migrations over a vast period of time. While some Siddis achieved high status within royal courts in India, others were enslaved in the households of wealthy individuals. The multiple historical roots of the African presence in the Indian subcontinent is frequently missing in scholarly literature. Because of this lack of emphasis, many historians tend to treat the figure of the African as an outsider to India, which aligns with the view that ethnicity and race are universal categories.

A Single Narrative

An exhibition titled Africans in India: A Rediscovery, curated by scholars affiliated to the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in New York City, was launched in New Delhi at the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts. It highlighted the most visible aspect of the African presence in India: the ranked officials and elites in various courts throughout the subcontinent. One of the curators, Dr Sylviane A. Diouf, expressed the objectives of the exhibit as being two-fold: to establish the African presence in the subcontinent from the medieval period, and to connect this history to the present ‘Afro-Indian community’.[21] This installation was well received and was invited to launch at the United Nations headquarters in New York in February 2016, as part of the International Day of Remembrance of the Victims of Slavery and the Transatlantic Slave Trade. It also toured throughout major cities in India.

However, it may be said that there is no one Afro-Indian community. Instead, there are multiple communities with linkages to African ancestors—communities that are differentiated by where they presently live in India and by their particular genealogies. As the exhibition mentioned above tries to frame the histories of men like Malik Ambar as the histories of present-day Siddis and Habshis, the result is an exclusionary, rather than nuanced, portrayal of their sustained presence in the subcontinent. By trying to reclaim the African-ness of these historical subjects and of the present-day perceived Afro-Indian community, initiatives like this exhibition further culturally distance these people from India, making them seem foreign. (Fig. 2) As a result of this focus on their ‘difference’, present-day communities feel they must constantly assert their Indian identity.

Yet, why is this a narrative that is also appealing for historical scholarship? In 2006, African Elites in India: Habshi Amarat was published.[22] Ten years later, in 2016, Omar Ali wrote a book entitled Malik Ambar: Power and Slavery Across the Indian Ocean. Historical writing places importance upon textual sources and ‘the archive’. Most of the textual sources and paintings and photographic renderings are of high-status individuals in various courts in India. There are multiple sources which speak of Malik Ambar, including the Mughal Emperor Jahangir in his memoirs. What is more pressing, however, is the task of writing the diverse histories of the African presence in India, so that it includes those who may not be so properly documented, and about whom it is far more difficult to find and piece together archival fragments. The results of this work, however, would mean that these communities have more historical narratives that even they are unaware of. Take, for example, the men of Afro-Arab descent who joined the sixth and seventh Nizam of Hyderabad’s regiment of ceremonial guards known as the African Cavalry Guards. Traces of their narratives can be found in the form of immigration slips and judicial cases in the archives of the former princely state, photographs from royal collections and oral histories from their descendants.

Why has this narrative gained popular purchase within Indian society? One possibility is that it reifies these communities as African rather than as Indian. Another possible reason for its popularity is the suggestion that Indian society was, historically, a place where an African slaves could aspire to become a ruler, effectively erasing the reality that Indian social milieus were heavily stratified according to ethnicity, caste and locality. The danger with this single narrative is that it does not explain the complexity of the African presence in the Indian subcontinent, because it presents members of these communities as outsiders to the country rather than as people who worked to build the nation state that India is today.

The movement of Africans to India took place over a long period of time and has created multiple communities, therefore not all Siddis and Habshis are genealogically linked to elites or royal personalities. As a result, there needs to be a plurality of historical narratives in order to properly reflect the diversity of these communities. These histories need to include those who held positions of power, but also those who physically built the regional kingdoms, empires and the nation state.

Popular Culture and Contemporary Society

In the aftermath of the Asian Games in 1982, the Sports Authority of India devised a programme known as the Special Area Games Scheme to recruit potential athletes from economically depressed and rural communities. Amongst them were Siddis from the states of Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh. The initiative endorsed a ‘scientific’ approach towards recruitment and training by engaging social anthropologists along with athletic trainers. The programme, which included studies of geography and physical attributes, concluded that Siddis were genetically linked to the Kalenjin and Kisii tribes of Kenya who have experienced success internationally in track events.[23] Although some Siddis gained international acclaim through this programme, it was ultimately cut.

The Special Area Games Scheme and the exhibition on Africans in India mentioned above both presented current communities of African descent in India as belonging to one historical lineage. The athletics scheme, by relying on supposedly ‘scientific’ theories on ‘race’, homogenised Siddis who do not share geographic and temporal origins. The exhibit also presented a singular and cohesive Afro-Indian community defined by their ‘African-ness’, and focused on ‘elite’ Africans and not on the diverse processes of their migration to India. Both the programme and the exhibit did not consider the importance of intermarriages between Africans and members of the local population, which has contributed to dynamic identities for these communities of African descent. Instead, both the scheme and the exhibition showcased the communities using a nationalistic lens: these communities are valuable because they provide athletic, cultural and political benefits to India—suggesting that they are not valued in and of themselves.

In addition to not being valued, visual representations and the portrayal of the African presence in India within popular culture and contemporary society have resulted in racist characterisations. In 1920, Hakeem Mohammed Moizuddin Farooqui, a Hyderabadi man who had studied in Chicago, created an Unani medicine known as Zinda Tilismath.

Translated to ‘Living Spells’, this popular medicine is still used as a remedy for a wide variety of ailments ranging from common cold to asthma. Farooqui supposedly drew his inspiration for the logo from the African Cavalry Guards of the Nizam of Hyderabad.[24] This logo is one of the most recognisable brand images in present-day Hyderabad, as it decorates the backs of autos, sides of buses and doors of shops. The logo for this ointment is a bare-chested black African man carrying a spear on his back. His facial features, particularly the full lips, are especially prominent. (Fig. 3) Although it seems hard to believe that this logo was inspired by the A.C. Guards, who wore full military dress and were equipped with carbines and sabres, this representation is consistent with racist textual characterisations by white American and European authors, who wrote about this regiment in newspapers and in their travel accounts.

During an event at the 1868 Langar procession (an annual event in Hyderabad which drew local subjects and foreign dignitaries alike to view the Nizam’s military forces), a report in the San Francisco Bulletin quotes a spectator who commented how the A.C. Guards are armed with sabre and carbine, and how their saddles and horse appointments are on the model of European hussar equipment:

This corps is composed of the ‘pucka’ Africans, with the woolly head, thick lips and coal-black hue... Their uniform consists of a red fez, with dark blue tassel, a dark blue pelisse laced with silver, open in the front, and displaying a scarlet undercoat or waistcoat laced with silver, dark blue pantaloons and jackboots.…They were well turned out, and tolerably well mounted.

Despite the equipment, accoutrements and horses which were on par with European equipment, the spectator surmised that the A.C. Guards did not perform as well as other military regiments, by referring to the A.C. Guards as 'Africans', and other regiments through military titles such as 'lancers' and 'soldiers', thus revealing racist undertones:

Following them came a regiment of lancers, a really soldierly-looking sort of men, infinitely superior, in my humble opinion, as to physique and getting up, to the Africans…they appeared to be admirably dressed and equipped, and sat their horses better than the Africans, who have rather a lounging, slouching appearance.[25]

The only remaining written accounts of the Langar procession are from American and European perspectives, in which there is a focus on the physical attributes of the A.C. Guards. Mohammed Owaisuddin Farooqui, grandson of the founder of the Zinda Tilismath brand, commented that his father had found the A.C. Guards visually arresting.[26] ‘It’s like when you have a room full of white people, and there is a black person, they stand out.’ The company’s official handbook states that ‘during the ‘Nizam’s regime, this African Negros were in the Nizams security forces and their overall physique was the sign of good health, strength, and trust.’ The usage of this logo by Zinda Tilismath suggests a fetishisation by Hyderabadis of the racial attributes of the A.C. Guards. It is especially interesting to note that, by 1920, most of the regiment would have contained muwallads, an Arabic term that the Nizam’s government employed to mean ‘children of the soil’, or those who were born to Siddi/Arab fathers and local Deccani mothers. There is photographic evidence of muwallads in the A.C. Guards as early as 1898, in a major compendium of photography and writing on Hyderabad’s history, cultures and peoples, published by Arthur Claude Campbell.[27] So the presence of muwallads, coupled with written and photographic records of uniformed and decorated A.C. Guards, contrasts with the Zinda Tilismath logo, which is evidence that in popular memory, the regiment has been reduced to racial caricatures.

Both in their use for nationalist gains through providing athletic, cultural and political benefits to India, and in their representation as racial caricatures, there is a great problem with how popular culture and contemporary society has dealt with the rich and enduring African presence in India. The consequence of these attitudes has been a diminution and distancing of their presence in India.

Conclusion

This piece attempts to provide the multiple pasts and presents of communities with linkages to African peoples in India. Presenting this community’s story helps investigate the parameters with which we define the boundaries of communities, and how we determine origins and descent. It also guides the usage of accepted analytics, like ethnicity and race, in determining origins, and suggests the question of whether this was always the historically accepted practice. The question of how origins are investigated and determined is important because of its tremendous consequences for peoples’ sense of belonging and their claims to particular histories.

Notes

[1] Khalidi, ‘African Diaspora in India,' 88.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Mamdani, ‘The Sidi: An Introduction,’ 16.

[4] Shroff, ‘Indians of African Descent,’ 315.

[5] Harris, ‘The Dynamics of the Global African Diaspora,’ 7–21.

[6] Ali, The African Dispersal in the Deccan.

[7] Sheriff, The Swahili in the African and Indian Ocean.

[8] Mamdani, ‘The Sidi: An Introduction,’ 9.

[9] Shroff, ‘Indians of African Descent,’ 36.

[10] Harris, ‘The Dynamics of the Global African Diaspora,’ 7–21.

[11] Singh, ‘African Indians in Bollywood,’ 273.

[12] Eaton, A Social History of the Deccan, 121.

[13] Bhatt, The African Diaspora in India, 50.

[14] Jasdanwalla, ‘African Settlers on the West Coast of India,' 45.

[15] Ali, The African Dispersal in the Deccan, 193.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ali, The African Dispersal in the Deccan,194.

[18] Padma, ‘Histories from Fragments'.

[19] Edwardes, By-Ways of Bombay, 82.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Sharma, ‘When Black Was No Bar'.

[22] Robbins and McLoud, eds., African Elites in India.

[23] Menon, ‘Special Areas Games Programme Launched to Groom Sports Talent’.

[24] Ifthekhar, ‘Wonder Drug Still Going Strong’.

[25] San Francisco Bulletin, ‘Remarkable Spectacle'.

[26] Mohammad Owaisuddin Farooqui, oral interview by Anisha Padma. Karkhana Zinda Tilismath. Hyderabad, India, April 2018.

[27] Campbell, Glimpses of the Nizam's Dominions, 100.

Bibliography

Ali, O.H. Malik Ambar: Power and Slavery Across the Indian Ocean (The World in a Life Series). USA: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Bhatt, Purnima Mehta. The African Diaspora in India: Assimilation, Change and Cultural Survivals. London: Routledge, 2018.

Campbell, A. Claude. Glimpses of the Nizam's Dominions. Philadelphia: Historical Publishing Co. 1898.

Eaton, Richard Maxwell. A Social History of the Deccan, 1300–1761: Eight Indian Lives. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Edwardes, Stephen Meredyth. By-Ways of Bombay. Bombay: D.B. Taraporevala Sons & Co Pvt Ltd., 1912.

Harris, Joseph E. ‘The Dynamics of the Global African Diaspora.’ In The African Diaspora, edited by Alusine Jalloh and Stephen E. Maizlish, 7–21. College Station: Texas A&M Press, 1996.

Ifthekhar, J.S. ‘Wonder Drug Still Going Strong.’ The Hindu, Hyderabad, December 27, 2000. Accessed July 15, 2019. https://www.thehindu.com/thehindu/2000/12/28/stories/0428403p.htm.