The ghazal originated in Arabia, evolved in Persia, and became the primary poetic form of Urdu in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, a period often considered the golden age of Urdu literature. Some of the greatest Urdu poets—Mirza Asadullah Baig Khan (‘Ghalib’), Mir Taqi Mir, Sheikh Mohammed Ibrahim Zauq, Mirza Muhammad Rafi Sauda, Bahadur Shah Zafar (the last Mughal emperor), Momin Khan Momin and Daagh Dehlvi—used ghazals as their primary form of creative expression. The tradition continued well into the late nineteenth century. Ghazals also became a significant poetic form for popular Hindi film lyricists, many of whom—Shakeel Badayuni, Sahir Ludhianvi, Majrooh Sultanpuri, Faiz Ahmed Faiz and Hasrat Jaipuri—had been accomplished Urdu poets before becoming film lyricists.

Urdu ghazals, as poetry and a gayaki (singing style), have influenced experiments in other Indian languages, especially Hindi, Marathi and Bengali. By the time ghazals were being written in these languages, the Hindi heartland, Maharashtra and Bengal were already familiar with North Indian performing arts traditions like khyal (a sub-genre of Hindustani music, literally meaning ‘imagination’) and thumri (a form of light classical music). While Hindustani music evolved primarily in the Maratha regions (Baroda, Kolhapur, Indore, Gwalior, Pune and Mumbai) and North Indian regions (Delhi, Agra, Lucknow/Rampur, Atrauli and Patiala), Bengal too had trysts with North Indian performing arts, first through Muslim rulers from the thirteenth century onwards, and then through the artist entourage accompanying Wajid Ali Shah, the Nawab of Awadh, who was exiled to Calcutta in the nineteenth century.[1] Thus, although Kazi Nazrul Islam started writing Bengali ghazals only in the early twentieth century, Bengal was already familiar with the musical tradition.

Odisha’s case is significantly different owing to how it never experienced direct rule by Muslim rulers. Islamic influence on the local language and culture had been limited to a few places between Northern Odisha (close to the Bengal border) and Cuttack, where representatives of the Mughals and the attacking Afghans had established their camps.[2]

Importantly, Odisha has a strong tradition of indigenous classical Odissi music, which is significantly different from both the Hindustani and Carnatic musical traditions, and is often described as India’s third classical music stream.[3] Odissi music dominated the first few decades of Odia recorded music.

The Beginning of Experimentations in Odia Music

While Kavichandra Kali Charan Patnaik—expert Odissi musician, poet, dramatist and theatre person—started experimenting with newer forms of light music, its medium of propagation was primarily theatre.[4] In the absence of mass media, this new style of music could not gain much popularity. Patnaik made a few gramophone records, starting with the highly popular song 'Chakiri Jhakamari', but they were circulated only among the rich and royals who could afford gramophone players.

Experimentation in ‘popular’ music began around the 1960s. By this time, All India Radio (AIR) was popular in Cuttack, Odia films were being released regularly, and Odia records were being produced (though most still featured Odissi and devotional music). The radio, films and records thus played an important role in mass dissemination and consumption of music. The newly emerging urban culture provided a good opportunity for experimentation. As is the case with popular music across the globe,[5] this opened up space for a stream of music outside of classical and folk music to establish itself.

Akshaya Mohanty—composer, singer, and lyricist, who also wrote novels and short stories—is widely credited with driving this transformation of Odisha’s collective taste in music towards modernity. Mohanty, who was not classically trained, challenged musical traditions. He tried everything, taking inspiration from other regional music, Hindi film music, and American country music, even while experimenting with new forms. The most groundbreaking aspect of his music is his lyrics, which in turn was inspired by the newly emerging urban landscape and changing Odia culture during his times. Hence, Mohanty is credited as the pioneer of Odia ghazals, although there were isolated instances of ghazal writing before him.

Odia ghazals do not belong to the realm of traditional music or literature. In essence, they emerged as a sub-genre of popular Odia music and its tryst with modernity. Therein lies the peculiarity of Odia ghazals and the challenge associated with their study. Unlike traditional performing arts that have evolved over decades (often centuries) and have certain accepted, if not always strictly defined, characteristics, popular music is individualistic and evolves quickly.[6] The fact that popular culture(s) in India is hardly explored in academia adds to the challenge of studying them. While there have been many acclaimed studies on Odissi and folk music, very little research exists on popular Odia music, let alone Odia ghazals.

This article traces the history of ghazals in Odia—both as literature and recorded music—and highlights significant trends in its trajectory. Research for this article has been done by examining the available body of works in ghazals (both audio recordings and those in textual form), earlier research done on the subject (mostly limited to ghazals till the 1990s, which are in textual form), and interviews with researchers and practitioners of the art form. It does not venture into the territory of analysing the actual content of the lyrics and music, and keeps largely to the history and ethnomusicological aspects.

What Is a Ghazal?

In the twentieth century, ghazals moved beyond mushairas and baithaks (musical gatherings) and became popular among the general public. Two streams of ghazals emerged: those which appeared in films, and those that were popularised by practitioners and the mass media. Works in the former stream, although popular, were never identified as ghazals, whereas the latter were.

Although ghazals have a large audience today, their key characteristics are lesser known. Many people wrongly believe that any serious romantic song is a ghazal; several associate ghazals with certain singers, such as Jagjit Singh, Ghulam Ali or Pankaj Udhas.[7]

Ghazals were traditionally sung by the poets themselves or by tawaifs (courtesans who catered to the nobility) in North India. Typically accompanied by the sarangi, rabab, and tabla, ghazals have also been performed with the sitar, sarod and harmonium; today, keyboards are also used. As they were often sung by the poets themselves, ghazals came to be known for their emphatic rhyme schemes rather than their sophisticated musical intricacy.

Ghazals are usually songs of separation which express the intensity of love beautifully. Sometimes, they explore mystic ideas; for example, Ghalib’s ghazals move seamlessly between earthly love and the love of the divine. Traditionally, ghazals were pessimistic and a form of male expression, even if women performed them. This is in contrast to thumris , which are considered female expressions of love even when sung by males. Thumris often consist of complaints against the beloved—there are several which revolve around the Radha–Krishna theme. However, they are not pessimistic—there’s always a craving for reunion; never hopelessness. In contrast, in ghazals, the poet often blames the beloved, God, and the world for his anguish.[8]

These are some of the characteristics of the ghazal—in terms of musical style and theme—that have evolved over time, but they cannot be considered as its definition. The ghazal is defined by its precise poetic form (rather than its musical style or theme), and when ghazal writers violate rules, they do so intentionally. Many Hindi film ghazals are not about separation; however, they are considered ghazals because they conform to the ghazal poetic form.

The classical music community considers the ghazal a light form akin to thumris. But a ghazal is more similar to sonnets or limericks than khyals, thumris or ballads.

A ghazal, thus, is a collection of couplets (shers) of equal meter or number of syllables (behr). One or more words (radif) are repeated in both lines of the first couplet and in the second line of each subsequent couplet. The word preceding the radif (called qafiya) in each couplet must rhyme. Shers stand independently, but together, they may express a central idea.[9] The first sher is called matla, and the last sher that contains the poet’s pen name (takhallus) is called maqta.

Odia Ghazals: A Neo-Art Form

Early Days of Odia Ghazals

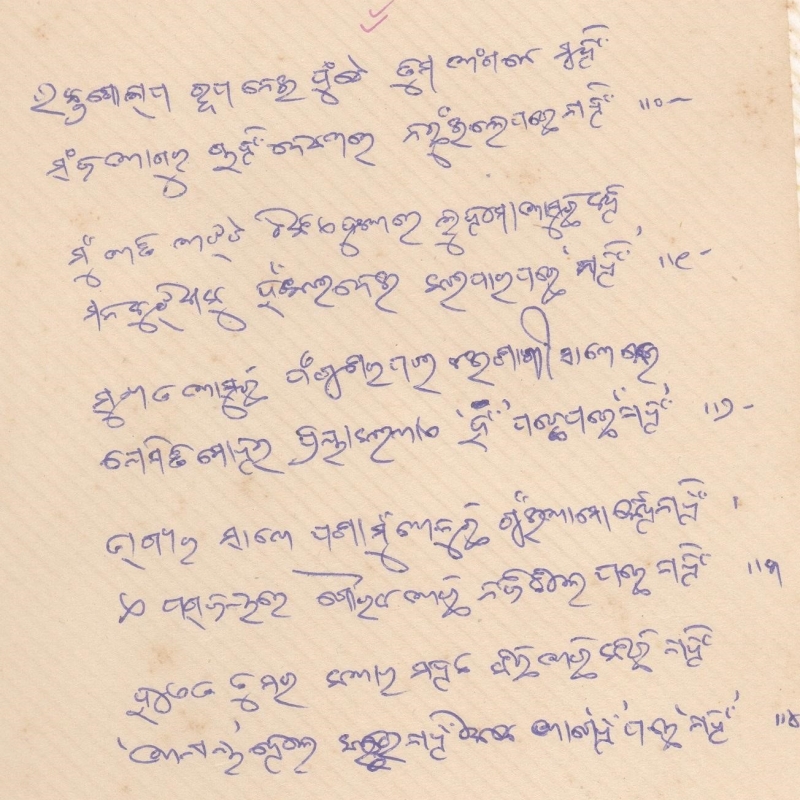

In 1925, Kavichandra Kali Charan Patnaik wrote a poem in his play, Kautuka Chintamani (A Treatise on Humour)[10] the first lines of which went:

Ka kunje puhai rati asila range nagara go

Daki delaki kajjalapati phula seja bhula sagara go

In whose grove did you spend the night, o lover boy

The black drongo calls, time to forget the bed of flowers

This marks the first instance of a ghazal being written in Odia, although Kavichandra never identified it as such. Kavichandra was one among those responsible for introducing modernity in Odia music, even while maintaining its roots in traditional dance and music through his theatre group.

In 1932, the Gramophone Company, through its HMV label, released a disc containing the song 'Jochhana Tale Mrudu Hillole' (Below the Moonlight, in Soft Waves), sung by Ghanashyam Ratha. This can be identified as the first formal reference to a recorded Odia ghazal. Although labelled as a ghazal, the song did not follow the ghazal poetic form. Between 1932 and 1936, 'Nia Ahe Priya Sneha Anjali' (Take, O Beloved, the Offering of Love), sung by Akshoy Kumar Das (Jr) was released, which was also described as a ghazal, despite not following the ghazal poetic form.

These releases are important in the study of Odia ghazals because they indicate public fascination with the term from as early as the 1930s, and the tendency to label non-ghazals as ghazals, which continues till today.

The only other Odia ghazals before Akshaya Mohanty’s time were written by Mahavidya Bohidar—under the pseudonym of Mehjabin Baleswari—and were published in 1961–62 in Ajikali, a periodical published from Balasore in North Odisha. According to Odia Ghazalra Sankshipta Itihasa (A Brief History of Odia Ghazals),[11] this is the first published series of Odia ghazals that followed the poetic form.

The 1960s and Akshaya Mohanty’s Contribution

Most researchers and practitioners agree that Akshaya Mohanty started the ghazal tradition in Odia. These people include: Mohammed Ayub ‘Kabuli’, who wrote a book on the history of Odia ghazal writing;[12] noted Odia poet Haraprasad Das, who has published a compilation of ghazals,[13] and who dedicated his book to Mohanty; Rafia Rubab, who published a well-researched piece on Odia ghazal writing in Kadambini;[14] and Pranab Patnaik, one of Odisha’s most popular singers, a contemporary of Mohanty and an accomplished Urdu ghazal singer.[15]

Mohanty is also credited with shaping the musical taste of modern Odisha. In his work, he balanced tradition and modernity, the rustic and urbane, commercial popularity and experimentation. Mohanty was inspired by everyday life and global literature.[16] Early in his career, he was treated as an outsider because of his lack of musical training. So, as a rebellion almost, he explored musical genres outside of traditional Odia music, and ghazals were the perfect creative outlet.

Mohanty understood the ghazal and went beyond just conforming to its poetic form, unlike many from more literary backgrounds. He actively discussed the ideas, metaphors and twists used by contemporary poets like Nida Fazli and Qateel Shifai, according to close friend and creative partner, Devdas Chhotray. Mohanty often combined ghazals and ghazal-style poems (consisting of two-line rhyming stanzas) in his books. He also modified the ghazal poetic form slightly to make it more suitable for Odia; subsequent Odia ghazalkars (ghazal lyricists) followed his form. Mohanty wrote the following variations:

- Ghazals that strictly satisfy all the poetic rules of the form.

- Poems with a minor compromise—the first line has no qafiya. However, the second and all subsequent even lines (second line of each couplet) have both a radif and qafiya. Some Hindi film ghazals follow this pattern.

- Poems with radif but no qafiya.

- Poems with rhyming (not the same) words at the end of each even line, which cannot be called a radif. These are typically poems with an ABAB rhyme scheme.

- Any poem with two-line stanzas, even with an AABBCC rhyme scheme.

For this research, only the first three categories are considered ghazals. The fourth category is referred to as ghazal-like. However, several lyricists consider even those in the fourth category as ghazals.

Mohanty released the first Odia ghazal album, Kalankita Nayaka, in 1984. The hit song, 'Kalankita Ei Nayaka' (This Disgraced Protagonist), had already become popular following its broadcast on AIR, but few recognised it as a ghazal. Mohanty actively encouraged others to perform the ghazals he wrote. Notable singers who have done so include Pranab Patnaik, Chittaranjan Jena and Bibudendra Das, all for AIR. Only some of these recordings are available publicly. Paradoxically, Mohanty did not record many of his own ghazals—it is unclear why. Haraprasad Das theorises that his commercial popularity did not allow Mohanty to experiment with ghazals, which required effort to sell to the general public. The fact that he always sang ghazals and ghazal-like songs in private sessions indicates his love for them.

Odia Ghazals as Literature

Apart from Kavichandra’s work in 1925, there was no visible ghazal writing until the early 1960s. Then, Mahavidya Bohidar wrote her series in Ajikali and translated some classic Urdu ghazals—many of which were published in Allola (Ripple). Mohanty’s Geeti (Lyrics), published in 1968, is generally considered the first Odia ghazal compilation, based on the research done by Mohammed Ayub Kabuli and Rafia Rubab—the only two researchers who have conducted focused research on the history of Odia ghazal writing. But he actually published Ei Katha Rahila (The Promise Remains), which contained 15 ghazals, in 1962. Later, the poems in these compilations, as well as new ones, were compiled in Madhushala (The Wine Bar), in 2001. Madhushala is considered the most important compilation of Odia ghazals in the tradition, although only 38 of its 50 ghazals adhere to the rules of the first three categories. Of this, seven are ghazals with radif and qafiya; four have no qafiya in the first line of first stanza; and 27 have a radif but no qafiya.

Since then, a few dedicated poets have attempted to write ghazals and translate Urdu ghazals:

- Nandkishor Singh’s Geeti O Ghazal (Songs and Ghazals;1977): Apart from Mohanty, Nandkishor Singh is probably the only popular Odia lyricist who has published a full compilation of ghazals. All other major Odia ghazal writers come from literary backgrounds.

- Laxmidhar Nayak’s Ghazal Jharna (Stream of Ghazals; 1989): Arguably the most important Odia ghazal book after Mohanty’s, this compilation contains 90 traditional ghazals, 41 devotional ghazals and 13 patriotic ghazals.

- Kudrat Ali Kudrat’s Bichi Bichitra (2006): The book contains nine ghazals, some of which were in the Urdu mystic ghazal tradition.

- ‘Zafar’ Akbari’s Shrabani (The Monsoon Maiden; 2006): This collection has 60 ghazals, which strictly conform to the poetic form; it includes songs of separation, love, mysticism and nationalism.

- Kabuli’s Smruti Lahari (The Wave of Memories; 2006): This compilation contains 15 ghazals.

- Devdas Chhotray’s Hati Saja Kara (Arrange the Elephant) (2008): Though Chhotray penned many ghazals, this book contains only a few.

- Ajay Kumar Mohanty’s Rati Jae Jhumi Saqi Jae Chumi (The Night Swings in; the Barmaid Kisses; 2010): This book contains classic Urdu ghazals that adhere to the poetic form.

- Antaryami Mishra’s Madhabira Madhurati (Madhabi’s Honeymoon; 2015): Although this book by the noted poet and lyricist claims to be a ghazal compilation, it contains just two or three ghazals.

- Haraprasad Das’s Abadhutara Diwan (The Ascetic’s Collection; 2016): This compilation by the noted Odia poet and Moortidevi Award winner is among the most acclaimed Odia ghazal books.

Translations of Urdu ghazals: Urdu is one of the least translated languages into Odia, but there are some translations of Urdu poetry, in particular, into Odia. Most Odia ghazal writers, with the exception of Akshaya Mohanty, have attempted to translate classic Urdu ghazals. Laxmidhar Nayak was commissioned by the Sahitya Akademi to translate Ghalib to Odia; others like Haraprasad Das, Mehjabin Baleswari, Nandkishor Singh, Shamsul Haque and Mohammed Ayub ‘Kabuli’ did so of their own volition. Unsurprisingly, Ghalib is a favourite among translators—his Dil-e-Nadan has probably been translated the most.

The body of translated Urdu ghazals is small. One challenge is the number of words/syllables. According to Mohammed Ayub ‘Kabuli', an Urdu sher requires almost twice the number of words in Odia. This makes conforming to rules with respect to radif, qafiya, behr, etc., quite difficult. Translators also struggle to reconcile the different metaphors and similes in the two languages, and variations in context and meanings. For example, autumn (khizan) is a period of despair in classic Urdu poetry, but a season of festivity in Odisha.

Recorded Odia Ghazals

It is difficult to trace the first recorded Odia ghazal, even though it was most likely recorded in the 1960s. AIR’s Cuttack station recorded the first few ghazals, although they were never identified as such. Many ghazals by Akshaya Mohanty and Nandkishor Singh were first recorded on AIR, but only a few are available today.

'Kalankita Ei Nayaka'—written, composed, and sung by Akshaya Mohanty—is the first formally released ghazal. Other ghazals—all written by Mohanty—recorded and broadcast by AIR include 'Jahara Ki Sura' (Poison or Wine) by Akshaya Mohanty, 'Se Kahin Aji Kahuthila Mote' (She Was Telling Me Today) by Pranab Patnaik, 'Mora Abujha Panaku Bujhi Na Pari Se' (Without Understanding My Persistence) by Chittaranjan Jena, and 'Tume Dekha Dela' (You Made an Appearance) by Bibudendra Das. Ghazals of other popular lyricists include 'Tume Aago Pahanti Ratira Bidhaba Janha' (You, the Fading Moon of the Dawn) and 'Kete Bhaunria' (How Many Ripples), sung by Pranab Patnaik and written by Debendra Das, and 'Snehata Bahuta Milila' (A Lot of Love Has Come My Way), sung by Mitali Chinara and written by Devdas Chhotray. In the 1980s, HMV released eight songs from Laxmidhar Nayak’s Ghazal Jharna, sung by Subash Dash.

Though other isolated efforts continued, the next major album, Nua Luha Puruna Luha (New Tears, Old Tears), containing six ghazals, was released in 2010. The ghazals were written by Devdas Chhotray, set to music by Om Prakash Mohanty, and sung by Susmita Das. Now, with the emergence of new media, several independent artists have made experimental recordings.

Conclusion

Ghazals are among the best forms for creative experimentation for artists such as Susmita Das, Namrata Mohanty and Adyasha Das, who have dedicated fan followings. Emerging artists like Manas R. Dash have also tried their hand at composing and performing ghazals. While it is presumptuous to claim that ghazals will become a dominant sub-genre, they will surely continue to occupy a special place within experimental modern Odia music.

Notes

[1] Sharar, Lucknow: The Last Phase of an Oriental Culture.

[2] Yamin, Impact of Islam on Orissan Culture.

[3] Dennen, ‘The Third Stream,' 149–79.

[4] Patnaik, Kumbhara Chaka.

[5] Tagg, ‘Analysing Popular Music,' 37–67.

[6] Monarch High School Human Geography, ‘Differences between Popular and Folk Culture’.

[7] Manuel, ‘The Popularization and Transformation of the Light-Classical Urdu Ghazal,' 348–60.

[8] Manuel, Thumri: In Historical and Stylistic Perspectives.

[9] Sturman, ed., The SAGE International Encyclopedia of Music and Culture.

[10] Patnaik, Kautuka Chintamani.

[11] Ayub ‘Kabuli,’ Odia Ghazalra Sankshipta Itihasa.

[12] Mohammed Ayub (researcher and writer) in discussion with the author, October 28, 2018, Cuttack.

[13] Haraprasad Das (noted poet and ghazal writer) in discussion with the author, October 29, 2018, Bhubaneswar.

[14] Rubab, ‘Odia Ghazal O Akshaya Mohanty,’ 66–70.

[15] Pranab Patnaik (popular singer) in discussion with the author, October 29, 2018, Bhubaneswar.

[16] Devdas Chhotray (popular Odia lyricist), email message to author, October 1, 2018; telephone discussion with the author, October 2, 2018.

Bibliography

Ayub ‘Kabuli’, Mohammed. Odia Ghazalra Sankshipta Itihasa. Cuttack: Mohd Sohrab Arshi, 2006.

———. Thumri: In Historical and Stylistic Perspectives. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1989.

Monarch High School Human Geography. ‘Differences between Popular and Folk Culture.’ Accessed July 15, 2019. https://monarchaphuman.files.wordpress.com/2013/08/differences-between-popular-and-folk-culture.pdf.

Patnaik, Kali Charan. Kautuka Chintamani (Kavichandra Granthabali, Vol I). Cuttack: Cuttack Students Store, 1968.

———. Kumbhara Chaka (Third Ed.). Cuttack: Cuttack Students Store, 1975.

Rubab, Rafia. ‘Odia Ghazal O Akshaya Mohanty.’ Kadambini (January 2012): 66–70.

Sturman, Janet, ed. The Sage International Encyclopedia of Music and Culture. USA: SAGE Publications, 2019.

Tagg, Philip. ‘Analysing Popular Music: Theory, Method and Practice.’ Popular Music 2 (1982): 37–67. Accessed July 15, 2019. https://www.jstor.org/stable/852975.