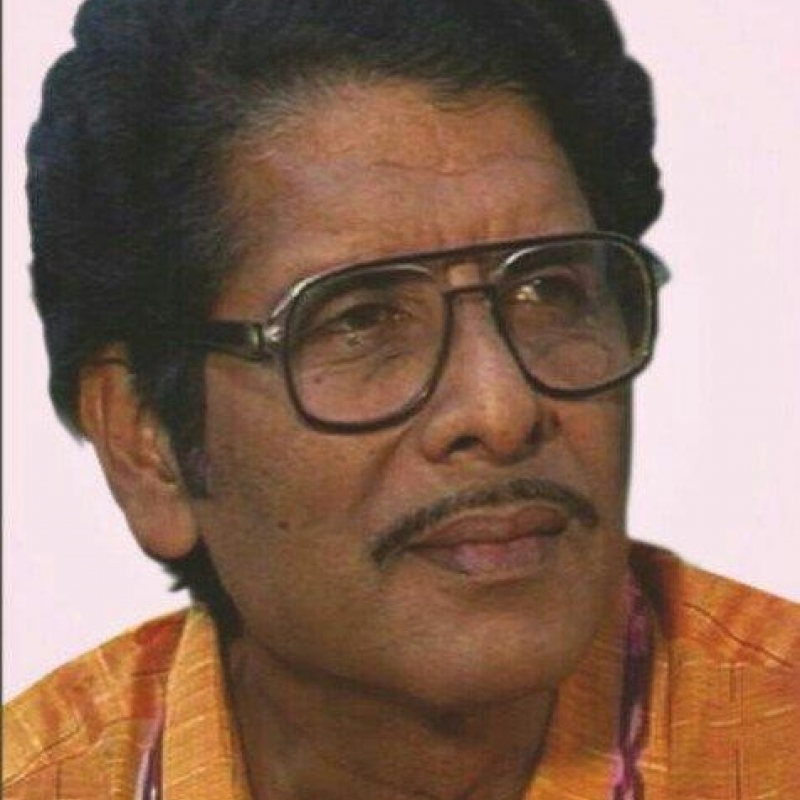

Akshaya Kumar Mohanty was not only a legendary singer in the Odia music tradition but also a cultural leader who managed to shape public taste in popular music by balancing creative experimentation and popular demand. Mohanty felt the need to embrace popular music for two reasons. The first was necessity; he became a professional musician early in his career and had to sell his music in order to make a living. The second was that he saw popularity as a means to influence public taste. In a way, he introduced 'modernity' to Odia music—a music tradition with strong roots in classical Odissi and folk music—by bringing in newer, more urban themes.

Though best known for his singing, his work as composer and lyricist is also extraordinary. While his singing helped popularise his music, his most serious experimentation can be found in his lyrics. And since he held the ghazal close to his heart, he wrote lyrics for a number of songs in this format. His work married the romanticism and spirituality of the ghazal with the everyday lives of people. He would take a thought from the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam and combine it with everyday experiences from his native city, Cuttack, to create a masterpiece that anyone could relate to. He had his finger on the pulse of the people, and he gave them music they wanted to hear while retaining his creative autonomy despite commercial pressures. This is evident in songs like 'Punyara Nadi Tire' (On the Bank of the River of Virtue) and 'Kalankita Ei Nayaka' (This Disgraced Protagonist), which had meaningful lyrics and yet were very popular.

To a dreamer like Mohanty, the form of the ghazal seemed to provide the perfect creative outlet. It is said that Diwan-e-Ghalib was always by his bedside.[1] Apart from the pure creative stimulation they offered, there might have been another reason for this choice. For a long time, Mohanty was excluded from the traditional music order because he was not trained in classical music. While most Odia musicians were trained Odissi singers, a few, like Sunanda Patnaik and Pranab Patnaik, had Hindustani training. Mohanty, thus, remained an outsider, and the ghazal became a creative way to express his rebellion—as music and poetry that had a Persian legacy, it stood in direct contrast to Odissi music. It is widely acknowledged that the ghazal parampara (tradition) in Odia started with Mohanty.

Though much of Mohanty's own songs were unrecorded, his influence on the genre is indelible, and in a way has shaped the Odia music industry. Mohanty often gave away ideas, opening lines, or stanzas to other lyricists who would then write the entire song. He would even add stanzas to songs by lyricists he was comfortable collaborating with, including Sibabrata Das, a versatile lyricist. The first line of Das' popular song, 'Nadira Nama Alasakanya' (Name of the River is Nonchalant Lass)—also considered a masterpiece in Mohanty’s career as a singer—came from him. However, the lyricist with whom he collaborated most was Devdas Chhotray.

It may be said here that Mohanty may not have been the first to write an Odia ghazal, but he was the first to popularise it in the streets. Stalwarts of Odia music testify to this view. ‘Akshaya tried this [ghazals] for the first time in Odia,’[2] says Pranab Patnaik, one of the pioneer singers in what could be considered 'modern' Odia music. In the words of Mohammed Ayub ‘Kabuli’, researcher and author of the book Urdu Ghazalra Chhayare Akshaya Mohantynka Odia Ghazal (The Ghazals of Akshaya Mohanty, in the Shadow of Urdu Ghazals), Akshaya Mohanty 'is the first real Odia ghazalkar (ghazal writer) to have written considerable number of Odia ghazals and placed a consistent focus on the genre, thereby starting a tradition.' [3]

Akshaya Mohanty’s Lyrics: Published, Unpublished and Recorded

Akshaya Mohanty published three compilations of his lyrics—Ei Katha Rahila (This Promise/Tale Remains) published in 1962; Geeti (Song), published in 1968; and Madhushala (Wine Bar), edited by Dr Renubala Mishra and published in 2001, a little before his death—during his lifetime. All three books are currently out of print, and the first one is unavailable even in libraries. Akshaya Mohantynka Gitakhata (The Lyrics Notebook of Akshaya Mohanty) was published posthomously, and primarily comprises his film songs.

While the first two books never claimed to be ghazal books, Madhushala, compiled and edited by Dr Renubala Mishra, carried a note from the publisher that it was a ghazal book.

Madhushala, which opens with arguably his most popular ghazal, 'Kalankita Ei Nayaka', has almost all the poems that have been recorded. Some of them include:

- 'Emiti Eka Bagichare' (In a garden like this), sung by himself for HMV Saregama.

- 'Parichaya Hela Alapa Bi Hela' (The introduction happened, the conversation happened), a ghazal that he has sung in many private recordings.

- 'Kalira Premika Aji Hasi Hasi' (Yesterday’s lover, today smilingly), a ghazal that he has sung in many private recordings.

- 'Se Kahin Aaji Kahuthila Mote' (She was telling me today), a ghazal, sung by Pranab Pattnaik for All India Radio.

- 'Dukhara Sathe Eniki Mora Alapa Heigala' (my conversation with my gloom just happened), a ghazal that he has sung in some private recordings.

- 'Dukha E Dehare Rahi' (Sadness, by remaining in this body), a ghazal sung by him in both private recordings and public shows.

- 'Ama Duhinkara Marame Jaluchhi Gotie Kisama Nian' (Similar fires are burning in the hearts of both of us), a ghazal that he has sung in some private recordings.

- 'Kalara Pujari Kala Puja Kari' (The worshipper art, by worshipping art), a ghazal that he has sung in some private recordings.

- 'Mora Ajhata Panaku Bujhi Napari Se' (She, not being able to understand my unflinchingness), a ghazal sung by Chittaranjan Jena.

It may be noted that the Odia ghazal does not always conform with all the aspects of the Urdu ghazal. A ghazal is a collection of couplets (shers) of equal meter or an equal number of syllables (beher), which usually fulfil a set of criteria. A refrain of one or more words, a radif, is repeated in both lines of the first sher and then in the second line of each subsequent couplet. The word preceding the radif in each couplet, known as a kafiya, must rhyme. While each sher must be able to stand on its own, together many shers may express one central idea.

The Odia ghazal can exist in the following variations:

- A song that satisfies all the above rules (7 such lyrics in Madhushala).

- A poem with a minor compromise—the first line has no kafiya, but the second line of each couplet has both a radif and kafiya. Some Hindi film ghazals follow this pattern. (4 such lyrics appear in Madhushala)

- A poem that has a radif but no kafiya. (27 such lyrics are there in Madhushala)

- A poem that has rhyming words at the end of each even line that cannot be called a radif, typically following an AB–AB rhyming pattern.

- A poem with two-line stanzas and an AA–BB–CC rhyming pattern.

In this discussion, we consider only the first three categories because a ghazal is often identified by its radif. Going by this definition, as many as 38 of the songs in Madhushala are ghazals or ghazal-like in that they are collections of couplets with a radif. His first book, Ei Katha Rahila, has 32 poems, of which only three fall outside the definition that has been considered. The other poems—barring seven—also form part of his last compilation, Madhushala.

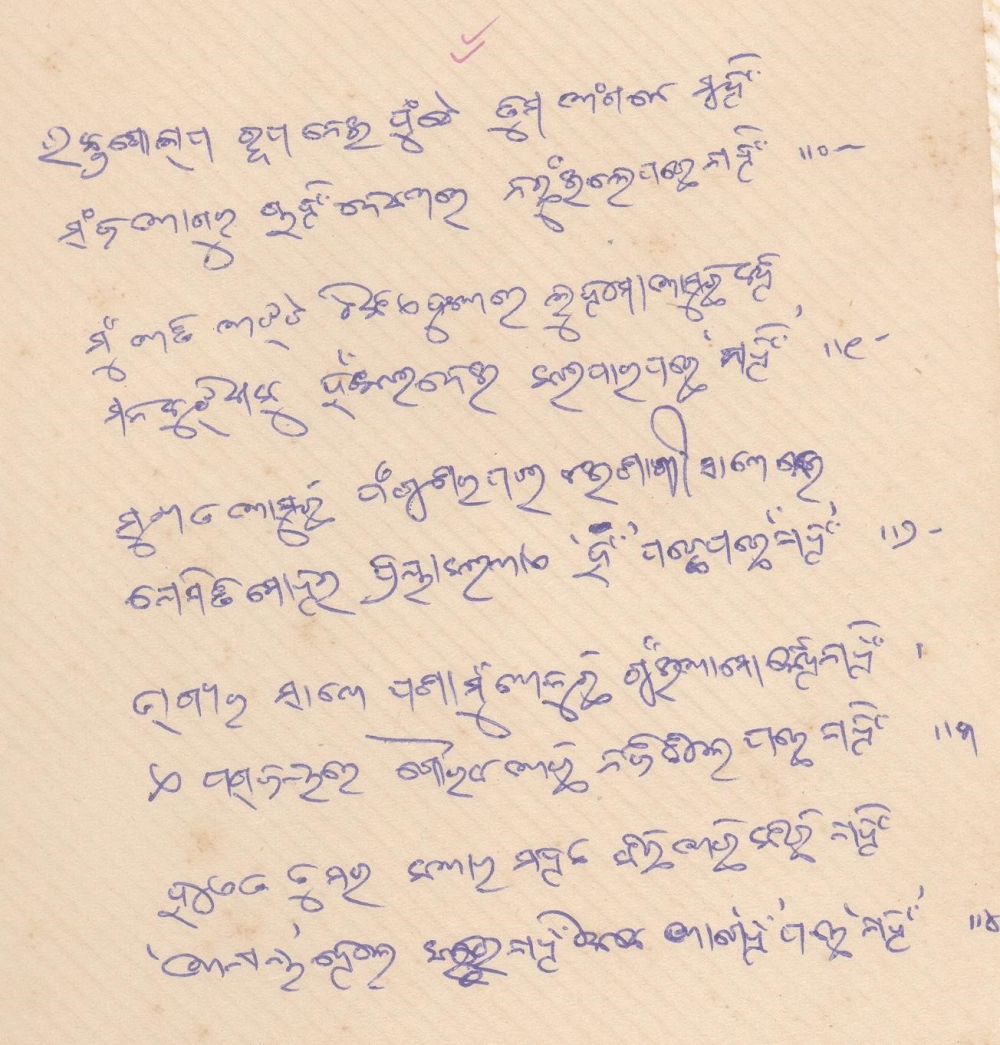

In addition, Akshaya Mohanty has a few unpublished ghazals. During this research, I found at least three such handwritten ghazals at his home, currently preserved by his son. They are:

- 'Aaji Puni Thare Mu Mane Pakai Die' (Today, Let Me Remind Again)

- 'Jhia’Nkara Mana Abhanga Kandhei' (The Girl’s Mind is an Unbreakable Doll)

- 'Rakta Golapa Rupa Nei Phute' (Blossoms as Beautiful as a Red Rose)

As previously mentioned, only a few of Akshaya Mohanty’s ghazals were recorded. In the late 1970s, AIR recorded and broadcast his ghazal, 'Kalankita Ei Nayaka'. It also recorded 'Se Kahin Aji Kahuthila Jie Bhala Paibata Shaja' (S/he Was Saying Today if Falling in Love is Easy), in the voice of Pranab Pattnaik.

In 1984, The Gramophone Company (popularly known by its brand name, HMV), under its Electric and Musical Industries Ltd (EMI) label, released an album, Kalankita Nayaka (Disgraced Protagonist/Hero), which was the first Odia album marked as a ghazal album. It contained four ghazal and ghazal-like songs, all written, composed and sung by Mohanty:

- 'Kalankita Ei Nayaka' (Disgraced Protagonist/Hero)

- 'Ete Dina Bhalapai' (After Being in Love for So Long)

- 'Maribaku Thila' (Had to Die)

- 'Emiti Eka Bagichare' (In a Garden Like This)

However, strictly speaking, the last two recordings were collections of couplets with rhyming last words.

AIR also recorded a few of his other ghazals, sung by popular singers Chittaranjan Jena and Bibudhendra Das. Yet, several others were not recorded at all.

Why did he not record so many of the ghazals he wrote, even after the popularity of Kalankita Ei Nayaka? His decision to restrict his ghazals from being used in films could still be explained—perhaps there were no cinematic situations that warranted such songs. But why not record independent albums or release music on AIR, considering he wrote some of these ghazals in the early 60s, when some of his songs had already brought him immense popularity?

Poet Haraprasad Das, an eminent commentator on literature and the arts in Odisha, offers one explanation. He describes Mohanty’s ghazal-writing—which was not his means of livelihood—as an avenue to channel his creative talent, but speculates that the pressures of the commercial world prevented him from venturing into more experimental territory. ‘Maybe he had no time to give that perfect touch to a ghazal that was close to his heart because of his professional pressures’, says Das. According to Das, his desire to record his ghazals after he established a presence in the Odia music industry did not come to fruition, as Mohanty died during the peak of his career.[4]

Though they may not have been recorded, he often sang these ghazals during private sessions with friends. Some songs that he sang in these private sessions include 'Dukha E Dehare Rahi' (Sorrow, by Residing in This Body), 'Kalira Premika' (Lover/Beloved of Yesterday), and 'Parichaya Hela Alapa Bi Hela' (We Met, Conversations Happened).

Mohanty’s ghazal-singing evolved over the years. While he was highly influenced by the ghazals of Ghalib (Urdu and Persian poet), Moumin Khan Moumin (Urdu ghazal poet from the Mughal era), Mirza Muhammad Rafi Sauda (Urdu poet) and Mir Taqi Mir (Urdu poet who contributed significantly to shaping Urdu language itself) in his early songwriting days, he did not adhere strictly to the ghazal gayaki (vocal stylistic tradition) while singing. The AIR version of 'Kalankita Ei Nayaka' is one example—it sounds more like Odia sugam sangeet (light music) than a ghazal. But by the time it was recorded for EMI and HMV, it had traces of ghazal-singing—especially the lehar (waving of voice) in the radif. In his later stage shows, it became even more prominent. In one of the most celebrated commercial recordings from his Silver Jubilee programme—recorded in 1984 at Shaheed Bhavan, Cuttack, and later re-recorded in the studio by JE Cassette Company in 1985—he sings and explains some aspects of the ghazal, like the maqta (the last sher or couplet). The impact of the ghazal gayaki is far more noticeable in his private recordings. For instance, his private recordings from the 1980s carried clear markers of the Urdu ghazal gayaki.

Akshaya Mohanty passed away in 2002, at the age of 66. It is probably more than a coincidence that in his last album, Twin City Queen, he sang a ghazal—'Harijaithiba Lokara Ki Achhi' (How Does It Matter to a Defeated Person?)—written in the quintessential defeatist, pessimistic style of the ghazal by his creative alter ego, Devdas Chhotray.

Notes

[1] Devdas Chhotray interview with the author; email received on October 1, 2018, followed by a telephonic interview on October 2, 2018.

[2] Pranab Patnaik in person interview with the author, Bhubaneswar, December 22, 2018.

[3] Mohammed Ayub Kabuli in person interview with the author, Cuttack, December 21, 2018.

[4] Haraprasad Das in-person interview with the author, Bhubaneswar, December 22, 2018.