The banyan tree (bat in Bengali; Ficus benghalensis), it is said, derives its name from the Indian banyan or merchant, by the way of Portuguese and English travelers who witnessed Indian merchants resting, praying, or conducting business under the shade of the said tree. Henry Yule and Arthur Coke Burnell’s Hobson-Jobson takes note of accounts of the tree dating all the way back to 1622. The ubiquitous banyan tree has historically lent its name to countless ‘battalas’ in Bengal (the suffix, tala, might refer to the space underneath, or might refer to the entire neighbourhood), spaces meant for gathering and rest, for worship and for business. One such battala in so-called ‘native quarters’ of colonial Calcutta, however, would go on to lend its name to a once-thriving print industry that is now remembered as the Battala print industry or simply, Battala.

There is no surviving banyan tree in the present day Chitpur-Garanhata area of Kolkata, no signboard that marks the site of the eponymous banyan tree. Historians and researchers have over the years attempted to track down the location of the battala, with multiple opinions of the possible location of the same. What remains with us are thus anecdotes about a ‘bandha battala’ (bandha, as in paved), under which gathered book merchants with their pile of cheaply-printed chapbooks (choti boi, in local parlance) and their buyers, very often hawkers who would source the books and sell them across the city and beyond. The print industry that grew around this battala, however, left its mark in contemporary history, despite being deemed a source of lowly and obscene ‘street literature’ (as Reverend James Long, the first chronicler of Battala would call it).

Colonial Calcutta’s earliest printing presses were European-owned, and primarily located in the area opposite Fort William, around the ‘Great Tank’ or Laldighi. Nathaniel Halhed Brassey’s A History of Bengali Grammar (1776) was the first book to be printed in Bengali type, though it is the efforts of William Carey’s Baptist Mission Press in Serampore, and the work of Charles Wilkins and Panchanan Karmakar that would lead to the production of Bengali type and printed books in Bengali in earnest. The earliest Indian-owned printing press in Calcutta was also established well outside of the Battala region—in Khidderpore, owned by one Baburam. However, it is the area around Battala that would see the proliferation of Indian-owned printing presses—Reverend Long would go on to identify 46 such printing presses in his 1857–58 survey. Sukumar Sen identifies similar printing presses well beyond the geographical confines of Battala, extending as far as Bhowanipore in the southern parts of the city, pointing to the fact that Battala lent its name not simply to the products of printing presses in the region itself but to cheaply-produced and sold chapbooks catering to a wide readership that nonetheless earned the ire of the custodians of ‘enlightened’ culture at the time. This, in fact, led to curious incidents like that of Basak and Sons—a printing press located in Darjipara (very much a part of the geographical ambit of Battala)—advertising a book called Gopal Bhand with the following inscription, 'This is not a fraudulent 20 page Battala Gopal Bhand imprint'. (Khastagir 70) Battala, then, meant more than a place—it would come to encompass all that was deemed lowly in the print industry at the time, all that would raise cultured eyebrows and mark considerable resistance from the educated Bengali elite as well as British missionaries such as Reverend Long.

Battala Literature and Obscenity

The immediate association of Battala literature, till date in Bengali parlance, is with ‘obscenity’, perhaps owing to the fact that the Battala printing presses did publish chapbooks of an outright sexual nature—chapbook sellers of present day College Street (a trade conducted mostly under the wraps, in a nod to everyday morality) could perhaps trace a direct lineage to these chapbook-sellers of the yesteryears. Bharatchandra Ray Gunakor’s medieval text, Bidya Sundar, retained its popularity, despite the criticism it received from many quarters. Reverend Long’s catalogue of Bengali books lists a considerable number of titles such as Adirasa, Beshyarahashya, Charuchittarahashya, Hemlata-Ratikanta, Kaamshashtra, Kunjaribilash, Lakshmi-Janardanbilash, Prembilash, Premnatak, Premtaranga, Premrahashya, Pulkan Deepika, Shringar Tilak, Ratibilash, Ramaniranjan, Rasamanjari, and so on. Long’s comment on the aforementioned books is equally memorable, 'These works are beastly equal to the worst of the French school'.

The names of the authors of these texts reveal a combination of a variety of caste groups contributing to the corpus of erotic literature: Benimadhab Chatterjee, Jadunath Pal, Jagatchandra Bhattacharya, Kalikrishna Das, Pitambar Bhattacharya, Prasannachandra Gupta, Rudra Bhatta, Tarapada Das, Panchanan Banerjee, Madhusudan Seal, Umacharan Trivedi, and so on. Authors of considerable education and social status would also write erotic texts of this nature—for instance, Dwarikanath Roy, a student of Sanskrit College, wrote Rasaraj; Madanmohan Tarkalankar wrote Rasa Tarangini; Akshaykumar Dutta wrote Anangamohan (to his later embarrassment). Bhabanicharan Bandopadhyay, a strident representative of conservatism and the publisher of Samachar Chandrika, wrote the Dutibilash after a demand from Swarupchandra Mullick, the seventh son of Nimaichandra Mullick, a babu of considerable wealth and social standing.

The printers of these texts, in order to attract their readership, would often include salacious images within. Their popularity attracted the ire of various sections of the society, with Reverend James Long taking an active role in demanding a law against ‘obscene’ publications. This would eventually lead to the Obscene Books and Pictures Act of 1856. Prominent social reformers like Keshab Chandra Sen of the Brahmo Samaj would form a society to prevent ‘obscenity’ in 1870, with members like Raja Kali Krishna Deb, Reverend Wenger, Munshi Amir Ali, Reverend Krishnamohan Banerjee, and so on. It is difficult to determine whether their attempts to demolish what they deemed the social disease of ‘obscenity’ had much impact beyond the arrest and punishment of a few publishers and hawkers, but it did earn for Battala the association with ‘obscenity’—an association, as contemporary scholarship has shown, that has obscured the vast variety of popular literature that the Battala printing presses churned out.

The Genres of Battala: A Brief Glimpse

If erotic publications constituted but one aspect of Battala literature, then what else did the Battala printing presses publish? The answer to that, in brief, might simply be: almost everything. The Battala presses catered to a wide variety of readership and produced an astonishing variety of genres, starting with the humble panjika (almanac) and the ubiquitous Ramayana-Mahabharata-puranas, to schoolbooks and primers, biographies and advice manuals, plays, poetry, novels, jatra texts, texts on farming and animal husbandry, recipe books, even manuals on photography. The two surviving publishers in present day Chitpur, Diamond Library and Mahesh Library, bear testimony to this variety to an extent.

The most widely-sold of Battalas’s publications were in fact the panjikas which ran the traditional manuscript panjikas out of business and competed with each other in terms of price. Reverend James Long estimated an approximate production of 250,000 almanac copies per year, saying, 'The Bengali Almanac is as necessary for the Bengali as his hooka or his pan [betel leaf], without it he could not determine the auspicious day for marrying… for first feeding an infant with rice… commencing the building of a house, for boring the ears… when a journey is to be begun, or calculating the duration or malignity of a fever'. Anindita Ghosh (133) has pointed out that:

… from the 1850s onwards, came to contain lists on weights and measures, postal rates, railway timetables, medical memoranda, rules and tables of fees in small case courts, list of public holidays, and numerous advertisements for Battala books. The lists, simple at first, grew in dimension to include even names of commercial agents and schools and colleges in Calcutta, while woodcut pictures of railways appeared side by side with those of Hindu divinities. It has been suggested that the new almanacs were modelled consciously on the European diary, in order to make them more useful to common people.

The printers of Battala, furthermore, made good of the increasing demand for primers courtesy the expansion in formal education (or, as it was known, ‘English education’). While the primers produced by Ishwarchandra Vidyasagar (Barnaparichay) and Madanmohan Tarkalankar (Shishushiksha, Vol I and II) were deemed the standard texts for young learners and published by the Sanskrit Press, Battala printed primers like Shishubodhak and Balyashiksha, that sold a considerable number of copies as well. Educational books constituted a considerable bulk of texts published in colonial Calcutta, both by the ‘respectable’ presses like Serampore Mission Press, the School Book Society press, the Sanskrit Press, as well as the various Battala presses.

One of the most questioned Battala genres, apart from the erotic texts, was the ‘gupta katha’ (secret), the most popular of which is undoubtedly Bhubanchandra Mukhopadhyay’s Haridaser Guptakatha (1898). Haridaser Guptakatha, the tale of a young man’s unfortunate life as he stumbles from one villainous figure to another and experiences the seamier aspects of life (murder, adultery, licentious women, and so on) before discovering his regal ancestry, went on to be embedded in Bengali cultural memory as an illicit read that was nonetheless irresistible to avid readers. The ‘gupta katha’ genre, adapted from JMW Reynolds’ pulp The Mysteries of London and The Mysteries of the Court of London (which, in turn, derived inspiration from Eugene Sue’s The Mysteries of Paris), gained unexpected popularity, perhaps courtesy the very gossip, crime, and engagement with taboo topics that was frowned upon by the polite society. Sensation would in fact remain a staple of Battala—the Elokeshi-Mahanta affair (a contemporary scandal involving a mahanta of the Tarakeshwar temple and an adulterous wife, Elokeshi, ending in the decapitation of the Elokeshi by her aggrieved husband, Nobin), for instance, prompted countless narratives such as Nandalal Ray’s Elokeshi Mahanta Pachali, which went up to 11 editions. A murder in Sonagachi, quarters noted for prostitution, prompted texts like Akhilchandra Dutta’s Sonagajir Khoon and Sonagajir Khooni-r Phansi-r Hukum. The scandalous affair between Upendra Basu and his niece, Kshetramani, would prompt narratives like Aghorechandra Ghosh’s Mama Bhaginir Pachali and Uh! Mama-r Ki Bichar, Krishnalal Chandra’s Mama Bhagini-r Bilap, and so on. It is perhaps unsurprising that by the turn of the century, Battala would go on to produce a thriving corpus of crime and detective fiction, featuring the works of writers like Priyanath Mukherjee (Detective Police, Darogar Daptar) and Pachkori De (Hatyakari Ke?, Goyendar Greptar).

Battala’s ties to the Bengali stage, both the emerging public theatre as well as the jatra, is well-documented; present day Chitpur continues to house offices of jatra parties, and the printmakers of Battala continue to cater to the publicity needs of these jatra houses, albeit in their modern offset printing machines. Battala, in the 19th century, published plays as well as jatra palas. Of these, the farces in particular gained particular significance; Jayanta Goswami (1974) has documented the publication of as many as 505 farces or prahasans in 1854–99, not all of them from Battala. The farces were oriented around various social issues, from adultery to licentious babus to the potential evils of women’s education, with authors like Michael Madhusudan Dutt, Amrtilal Bose, and Dinabandhu Mitra defining the best of the genre. However, Battala’s farces were of a considerably broader stroke, often focusing on the critique of the ways babus and bibis (Bechulal Benia’s Sachitra Hanumaner Bastraharan, Nemaichand Seal’s Erai Abar Borolok, Harimohan Karmakar’s Mag Sarbashya, anonymously composed farces like Meye Monster Meeting and Novel Nayika ba Shikkhita Bou), and the perceived evils of modernity. Scandals like the Elokeshi-Mahanta affair found traction with farce writers as well. There is, however, very little evidence available as to whether or not the Battala farces, like their more respectable counterparts, were performed for audiences on the stage.

Another less-discussed aspect of Battala literature was the proliferation of what Reverend James Long called 'Mussalman Bengali Literature', and what later scholarship has named 'Muslim-Bengali' literature. Sumanta Banerjee (2013) calls it 'dobhashi' or 'bilingual literature', alluding to the generous mixture of Perso-Arabic and Urdu words with Bengali in the texts of this genre. The sentences in these books were often structured from right to left in a manner similar to Arabic and Persian, as opposed to the standard Bengali left to right. Aimed primarily at a Muslim readership and published both in Calcutta’s Battala as well as its twin in Dhaka’s Ketabpatti, Muslim-Bengali literature produced narratives centered around the life of the Prophet, as well as fairy tales and romances (such as Ameer Hamzar Puthi, Hatem-Tai, Yusuf-Zuleikha). However, there is considerable evidence from personal narratives drawn from the 19th century that suggests that Muslim-Bengali texts had a considerable Hindu readership as well. Hindu press owners did not hesitate to capitalize on the popularity of Muslim-Bengali texts; in fact, as per Reverend Long’s catalogue, Chaitanya Chundrodoy and Jnanodoy Presses in Battala routinely published Muslim-Bengali texts. It is in the 1880s that Muslim publishers took on the business of publishing in earnest—Anindita Ghosh has named Muhammad Jan and Munshi Male Muhammad of Dhaka, and Tazuddin Muhammad, Maniruddin Ahmad, and Mafizuddin Ahmad of Chitpur, Calcutta, as the dominant names in publishing Muslim-Bengali texts in the 1880s.

A Question of ‘Quality’

It was not, however, Battala’s propensity for publishing pornography or sensational narratives alone that led to its reputation for ‘obscenity’. The proliferation of print in colonial Bengal coincided with the expansion of formal education in the Western mode, as well as the so-called ‘rise’ of a class—often clubbed together as the bhadralok (bhadra, meaning respectable)—that capitalized on this expansion to secure for itself considerable clout in the society, securing business ties as well as positions in the civil service. The bhadralok, with their newly-gained cultural capital, threw themselves into the project of social reform and sought for themselves cultural hegemony over the much-disparaged chhotolok (‘small’ or less respectable people). The proliferation of print would emerge as an useful tool in this regard, as it allowed the publication and distribution of ‘appropriate’ reading material in the newly standardized Bengali language. Reformist literature and advice manuals of the period are thus inundated with anxious voices that bemoan the popularity of Battala literature with impressionable readers—first-generation learners from outside of the traditional literate castes, as well as women. For the less prosperous bhadralok professionals as well, as Anindita Ghosh (2010) has documented, the lure of Battala literature proved irresistible. Ghosh, thus, speaks of ‘contesting’ cultures of print, wherein the ‘low-life’ literature of Battala must necessarily be deemed ‘obscene’ and therefore unfit for consumption in order to valorize the literary and cultural sphere dominated by the upper caste, middle class men.

This strident disparagement of Battala, with the whiff of unsavouriness associated with it, did not necessarily affect the volume of its sales. Chandranath Basu, writing about the popular mythological plays produced in Battala in the 1880s, says:

These mythological dramas simply relate stories from the Puranas, the Ramayan, the Mahabharat, &c., in the form of dialogue, are always devoid of true dramatic characteristics, and seldom possess any literary merit. They seem to command, however, a large sale among orthodox people in the mofussil, where the book-makers and the book-sellers of Battala have an indefatigable and ingeniously contrived agency at work to promote the circulation of books. It is that agency which really ministers to the literary tastes and intellectual wants of the large rural population of Bengal who have not sufficient knowledge of English to understand or appreciate what is written by English-knowing Bengalis, and who are at the same time to strongly affected by the newly-created taste for novelty and the new fussy spirit to be satisfied with the plan, sober, simple and dignified narratives of Krittibas and Kashidas. (Librarian’s Report, Bengal Library Catalogue of Books, 1883)

Basu’s commentary on Battala literature in the aforementioned quotation is characteristic of that of the custodians of high culture, at once critical and almost envious of the ‘indefatigable’ and ‘ingenious’ spirit of Battala. The dismissal of the ‘taste’ of the readers of Battala literature and their seeming lack of appreciation for the writing of ‘English-knowing Bengalis’ displays a deep cultural anxiety, a sense—almost—of impending defeat at the hands of the less refined.

Chitpur, today, holds only two of the 22 book stores that survived well into the 21st century. A number of printmakers continue to operate out of Chitpur, catering primarily to the immediate needs of the jatra companies. The declining fortunes of Chitpur and the moving away of the print industry from the geographical confines of the erstwhile Battala has, nonetheless, not erased Battala or its literature from the cultural memory of Bengal. It continues to be invented and reinvented in popular culture and in the diligent work of historians of art and print, among others.

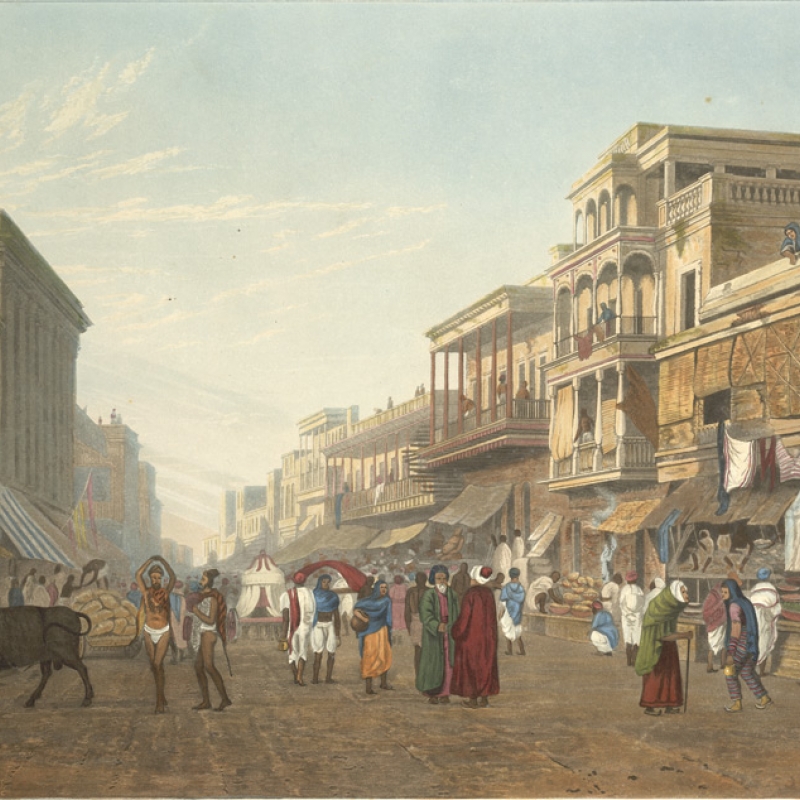

(Image: James Baillie Fraser's 'Views of Calcutta and its Environs', Plate 24, Aquatint; 1826)