An overview of Wayanad

Wayanad, a district of Kerala, is well known for its beautiful landscapes and sizeable tribal population. Located in the Western Ghats, the district is often called the 'Green Paradise of Kerala', owing to a total forest coverage of 37 per cent (Census 2011), significantly higher than in any other districts of Kerala. The district, located at the southwestern tip of the Deccan Plateau at an altitude of 700 m above sea level, extends over an area of 2,125 sq. km.

The district of Wayanad was created on November 1, 1980, as the twelfth district of Kerala by merging several areas of the erstwhile Kannur and Kozhikode districts. It is bordered by the states of Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, while Kannur and Kozhikode are its neighbouring districts on the Kerala side. Wayanad consists of three taluks (sub-districts)—Mananthavady, Sulthan Bathery, and Vythiri—and has a population of 8,16,558, constituting 2.45 per cent of the state’s population (Census 2011).

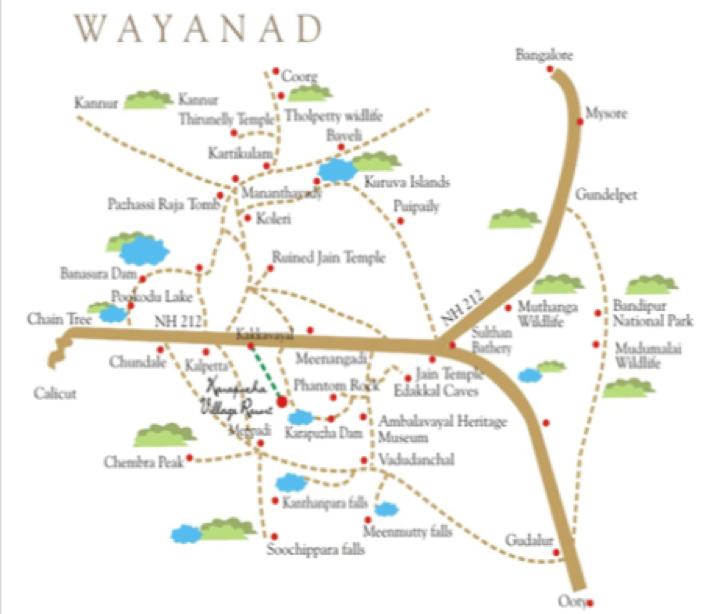

Figure 1: The District Map of Wayanad

The district is renowned for its tropical climate and its lush landscapes with green hills, valleys and forests. It is also popular for its paddy fields and extensive tea and coffee plantations, and its production of cash crops like pepper, cardamom, coffee, tea and other spices. Wayanad is rapidly emerging as a major eco-tourism location in southern India and is also well-known for its religious and cultural festivals, tribal ballads, tribal medicine and folk performances. In this context, it is important to emphasise the large Adivasi (tribal) population of this district—the Paniyar, Adiyan, Kattunayakan, Kuruma, and Kurichiya indigenous communities.

As per the data available from the draft report titled ‘Scheduled Tribes of Kerala: Report on the Socio-Economic Status’ published by the Scheduled Tribe Development Department, Govt of Kerala, in November 2013, the tribal population of the district stood at 1,53,181 with 36,135 tribal families. The population of scheduled castes and scheduled tribes (SCs and STs) comprised four and 17 per cent, respectively, of the total population of the district. Of the four administrative blocks in the district, Mananthavady had the highest tribal population (29.46 per cent) followed by Sultan Bathery (25.09 per cent), Panamaram (24.2 per cent) and Kalpetta (21.25 per cent) (Census 2011). The cultural fabric of Wayanad heavily derives from the cultural practices and ways of life of these indigenous tribal communities.

Agriculture is the most prominent source of income, as nearly 96.13 per cent of the population resides in rural areas (Kumar 2013). There are different accounts regarding the origins of the district’s name, and some of them indicate how closely agriculture is related to the culture, history and making of Wayanad. The name Wayanad may have originated from two vernacular words—‘vayal’ which means paddy fields, and ‘nadu’ which means land or place (Kumar 2013:105). Thus, ‘Vayal Nadu’ would mean the land of paddy fields. In tribal folklore, one can find similar interpretations (Vaisakh 2017). According to another interpretation, the region was known as ‘Mayakshetra’ (Maya’s land) in the earliest records. Mayakshetra evolved into Mayanad and, finally, to Mayyanad (Panchayath Level Statistics 2011:6).

Before delving into the tribal communities in Wayanad, some knowledge of the history of the district is necessary. Archeological excavations in the Edakkal Hills have found traces of human settlements dating back to at least 10th century BC (Johny 2001). Evidences of a Stone Age civilisation have be found in several parts of Wayanad. Pictorial writings and paintings on the walls of Edakkal Caves in the Ambukuthi mountains, about three kilometres from Ambalavayal, and megalithic burial sites discovered about seven kilometres to the west of the Edakkal Hills and also at Chingeri in Ambalavayal village, indicate the long history of human settlement in this region (Nair 1911:9).

The Kurichiya and Kuruma communities of Wayanad

The Kurichiya and Kuruma tribal communities are today included among the scheduled tribes in Kerala. The first mention of them in written records date back to the 18th century, and can be found in the works of William Logan (1887), Edgar Thurston (1909), T.K. Gopala Panikkar (1900), and Rao Bahadur C. Gopalan Nair (1911). Malabar Manual, by William Logan (1887), is considered a rich source for understanding the life and culture of the Kurichiya community. Logan vividly details in his work the lives and socio-economic situations of the people of the Malabar region. Edgar Thurston (1909), in his celebrated work Castes and Tribes in Southern India, gives a detailed account of the hill tribes of Kerala, focusing on the lives of, habits, manners and religious practices of communities like the Paniya, Kurichiya, Adiya, Kuruma and Kattunaika. Ayyappan (1965) has to his credit several studies on the various tribes of Kerala, one of which is on the socio-economic condition of the Kurichiya and Kuruma tribes. This article will rely on these sources as well as direct interviews with members of the community to shed light on the history, socio-economic condition and knowledge systems of these communities.

Kurichiya

Also known as Malai Brahmins or Hill Brahmins, the Kurichiyas are the second largest adivasi community in Wayanad district. They stand at the top of the caste hierarchy among the hill tribes of Wayanad, and used to practice pollution with all other caste and tribal communities except with Nairs and Nampoothiris. The community was named Kurichiya by the Kottayam Raja for the community’s expertise in archery. The name is derived from the phrase ‘kuri vechavan’, which means ‘he who took aim’. They are also said to have originated from a subsect of Nayars named Theke Karinayar, or Kari Nayars of the south, suggesting the Venad or Travancore part of Kerala (Gopalan Nair 1911:59).

Bindu Ramachandran (2003), in her paper titled ‘Fertility Concept in a Ritual: An Anthropological Explanation of 'Pandal Pattu'', has written about the mythological origins of the Kurichiya community:

In the distant past before creation, the sky was on the top and the earth lies far below covered by the sea. At that time, Vadakkari Bhagavathi, the Kurichiya deity had a dream in which the almighty ordered her to find out a place to create 1001 castes. God also allowed her to move the sea side wards and then start work. Young virgins were given as labourers. On completion of the work the worker went out to meet the God and asked for remuneration. But he objected to give the remuneration before examining the quality of the work. God created a bird called Chenthamarapakshi (bird from a red lotus) and asked the bird to fly around the earth and find out the quality of the work. After examination the bird found out a fault that in one place the work was incomplete. Two hills were standing close to each other without touching one another. There was also water in between these hills. On both the hills god created and placed 18 human castes, different types of animals and plants. Kurichiya believe that they are one among them.

Kuruma

The Kurumas are a tribal community who are believed to have descended from the Vedars, the ancient rulers of this region. This community mainly dealt with forest products (Thurnston 1909), and they were further divided into three subsects on the basis of their occupation: i.e., Mullu Kuruma (who collect bamboo), Then Kuruma (who collect honey), and Urali or Bettu Kuruma (who are wood cutters, fishermen, and artisans). Amongst these, the Mullu Kurumas consider themselves above the other two groups in the caste hierarchy. The Bettu Kuruma do not have any ethnic affinity with Mullu Kurumans, although they are classified as Kurumas (Binu & Rajasenan 2013:28). Presently, most earn a livelihood through agriculture and cattle rearing (George 2007).

According to popular belief, the Vedar kings ruled Wayanad for several years before they were defeated by the neighbouring kingdoms of Kottayam and Kurumbranad in the late 14th or early 15th century, following which the latter established their rule in Wayanad (Johnny, 2001:29). During the early 18th century, Kerala Varma Pazhassi Raja, the then Raja of Kottayam, conquered this region (Logan 1987). In the book Wayanadum Pazhassithampuranum (Wayanad and Lord Pazhassi), K.G. Madhavan Nair (1998) writes of how the Kurichiyas aided Pazhassi in waging war against the British.

The close of the 18th century witnessed a serious revolt against the British by Pazhassi Raja, who withdrew into the forest district of Wayanad to escape the colonial regime. Members of the Kurichiya and Kuruma tribes served in the army of Pazhassi Raja as bowmen while waging guerilla warfare against the British and helped the king find safe places to rest in the forest. These troops were led by Thalakkal Chanthu, a member of the Kurichiya tribe. At night, the Kurichiyas attacked the barracks of the British army, and would ambush them with volleys of arrows. For five years, Pazhassi Raja survived and continued his battle against the East India Company with the help of the Kurichiyas and Kurumas. They continually challenged British supremacy in the region and continued their struggle even after the death of the raja in 1805, confronting and fighting the British’s land taxes and land grabbing activities.

In April 1812, the Kurichiyas and Kurumas rose in revolt against the colonial government, for reasons including the government’s decision to confiscate their land. The tribal people were skilled archers, and they fought bravely against the British, despite the latter being armed with highly sophisticated weapons. The tribal people were experts in guerrilla warfare, but in the end, they were defeated, and a large number of warriors of both communities lost their lives. This battle is known historically as Kurichiya Kalapangal (The Revolt of the Kurichiyas) (Ravindran 1976). William Logan, an officer of the Civil Service, expressed his admiration for the valour and archery skills of the Kurichiya community (Binu & Rajasenan 2013:14).

Both the Kurichiya and Kuruma tribes are land-owning communities. They follow a matrilineal household system. They also share similarities in religious practices, rituals, festivals, language and food habits. Kurichiya refers to their settlements as tharavadu, muttam, etc. whereas Kuruma settlements were called kudi.

The Malabar migration, which started during the early decades of the 20th century and continued well into the 1970s and 1980s, is yet another historically significant event that influenced the social, environmental, cultural and political trajectory of Wayanad. Malabar migration refers to the large-scale migration of Syrian Christians from central and southern Kerala to the northern regions, popularly known as the ‘Malabar’, in the 20th century. These migrants were mostly from the present-day Kottayam and Idukki districts, though many arrived from hilly areas in Ernakulam district as well (Joseph 2002). Several Hindu Nairs also migrated and established settlements in hilly areas in the Malabar region. They focused on cultivating spices and other cash crops such as coconut, coffee, tea and pepper. This large-scale migration had an impact on the region’s land use patterns, forest ecosystems, and on the life and culture of tribal communities. The forests and hills that were previously freely used by tribal communities were transformed into plantations and an ordered productive landscape (Pradeep 2016:539–540).

Indigenous knowledge systems of the Kurichiya and Kuruma communities

The indigenous people of India are not a homogenous entity, and, in turn, the knowledge systems evolved among them are also complex, layered and diverse. The knowledge systems of these communities uniquely blend practical wisdom as well as skills, facts and knowledge passed down over generations. Each tribal sect has its own cultural heritage, developed over years of understanding, perception, and lived experience. In addition, each tribe has its own narratives about its relationship with nature and natural phenomena.

The Kurichiya and Kuruma communities have rich oral traditions—songs and stories on the history of the tribe, myths regarding their origins, and tales of gods. Oral traditions can be rich sources for understanding a community’s origin, history, experiences, expressions, ideas of divinity and perspectives about life and death.

The Kurichiya and Kuruma tribes are also known for their indigenous cultivation practices. They followed slash and burn (shifting) cultivation known as punam cultivation (Logan 1989). The types of rice and crops cultivated by these tribal groups were completely different from those used by the mainland and other tribal groups in Wayanad. Kurichiyas lost their cultivable land and dwelling spaces with the introduction of commercialized cultivation practices and the expansion of agriculture (Menon 1994). Traditionally, the Kuruma tribes did not cultivate cash crops, but due to the influence of settlers from the central part of Kerala, many in the Kuruma community started cultivating pepper and areca nut (Joseph 2002). However, the festivals of these tribes still revolve around rice farming and harvesting. Thulapathu, Puthari, and Uchal are the major festivals of these communities that celebrate the planting of paddy saplings and the harvesting of rice.

Even now, most paddy cultivation in the district is done by the Kurichiya and Kuruma communities. The agro-climatic condition of Wayanad is generally favourable for rice production. Today, these tribal communities use domesticated buffalos to plough the land, and hesitate to use tillers. The farmers of these communities are of the opinion that when they use tillers, they plough the land deeper than the few inches essential for paddy cultivation. Organic manure made of cow dung and decomposed plant residue is added to fertilise the land. Traditionally, planting the sapling is a ritual and is celebrated by festivities in this indigenous community. The head of each hamlet, the eldest male member, performs poojas in the Daivappura (a place of worship) and light the nilavilakku (traditional lamp), marking it as a special day. The celebration Thulampathu or Putthari (meaning ‘new rice’) is significant for this paddy farming culture, and often involves going hunting in the afternoon. On this day, special rituals are performed on the paddy fields.

In the post-Independence period there were a series of legal interventions such as the Forest Policy (1952), Wild Life Protection Act (1972), and Forest Conservation Act (1980) which reduced the privileges available to these tribal groups and they were forced to occupy land provided by the state (Bijoy 2011). Now, these tribes live as colonies of 30 or 40 houses, and they jointly own the land. Every member of the community contributes in farming the land. Hence, planting the sapling is considered an occasion for merry-making, a community activity, and a sacred practice.

It is noteworthy that indigenous methods of farming have helped to protect crops, including rice, from diseases. In additional, traditional methods of farming are more sustainable in the long run. The rich wisdom of the Kurichiya and Kuruma communities should be mined for ancient knowledge that can be integrated with new agricultural techniques. According to the Agriculture Department, the land under paddy cultivation in Wayanad was 8,000 hectare in 2015–16, as against 30,000 hectare in 1985-86. Rejuvenation of ethnic varieties of seeds and traditional ways of farming can restore the lost glory of the district.

The Kurichiya and Kuruma communities have extensive knowledge about paddy cultivation. Cheruvayal Raman, a native of Mananthavady in Wayanad and a member of the Kurichiya community, is an authority on paddy cultivation. He is the custodian of 53 varieties of paddy seeds that were traditionally used in Wayanad, and he can identify and name every variety by sight. He is recognised as a heritage paddy preserver by the Government of Kerala, and is a General Council member of the Agricultural University, Mannuthy. He was felicitated with the Genome Saviour Award 2016, instituted by Protection of Plant Varieties & Farmers’ Rights Authority of India (PPVFRA), for his lifetime efforts in the conservation of traditional rice varieties. Traditionally, the Kurichiya community preserved paddy seeds like treasure for the following generations. With a similar mindset, Cheruvayal Raman refuses to commercialise the seed preservation activity. Instead, he believes that they are physical manifestation of farmers’ love and carry inside them the dreams of farmers.

Figure 2: Cheruvayal Raman in his paddy fields. He is cultivating 53 varieties of rice here, each in small portions.

Cheruvayal Raman has preserved many rare and medicinal rice varieties, by cultivating them in his field. Karuthan and Pena are the wayanadan kara nellu (upland paddy) preserved by him. Raman is also of the opinion that traditional rice varieties have medicinal qualities too, if cultivated organically. During an interview with the author, Raman spoke of how a fried paddy mixture can be used to cure injuries and reduce leg swelling. Scratches on the foot can be treated with boiled paddy. Veliyan is a traditional paddy variety used in Wayanad, with a maturity period of above 200 days and resilient in adverse weather conditions.

Of all the varieties of rice that Raman grows, Kalladiaryan, Thavalakannan, Punnatan Thondi, and Onamottan can withstand drought. Paddy fields are environment-friendly as they not only provide natural drainage for flood waters, but they are also crucial for preserving a diverse range of flora and fauna. As a proponent of organic farming, Raman follows the lunar calendar to schedule his agricultural activities, including preparing the land, sowing seeds, and harvesting rice. For example, it is preferable to plant saplings on full moon days, as rodents are unlikely to come out on those nights and will not attack the young plants.

These indigenous agricultural practices have not been written down or documented in any form, though there is an increased awareness of the importance of these knowledge systems. There have been no studies on them, how they work, how they can be modified, or their operation, limitations, and applications. Studies to codify and integrate this traditional knowledge with modern agricultural practices can prove crucial not just for the preservation of intangible knowledge systems, but also for tackling issues such as food security and environmental degradation.

These tribes hold vast knowledge about indigenous water management and harvesting practices. Traditionally, tribes used bamboo drip irrigation to water their fields. Mullu Kurumas, who are skilled in the use of bamboo, reside in the panchayats of Noolpuzha, Kidanganad, Muppainad, Muttil, Parakkadi, Thirunelli, and Mananthavady and also in the adjoining Gudalur taluk in the Nilgiris. Panam keni is a special type of traditional well used by the Mullu Kurumas as their main source of water. Kenis are located either in the corners or in the middle of paddy fields, or near forests. In his article on traditional wisdom in harvesting water, G.S. Unnikrishnan Nair observed the following about Keni:

They are of cylindrical in shape; they have a diameter and depth of around four feet only. The wall is of Toddy palm (Caryota urens). Usually, the bottom stem portion of large palms are used to make wooden cylinders after retting them in water for a long time so that the inner core gets rotten and degraded and the hard outer layer remains. The wooden cylinders are immersed in the spots where there is good ground water spring and that are the secret of abundant water even in hottest summer months (Nair 2016:51).

Figure 3: A Keni

For the Mullu Kurumas, kenis are sacred and should be approached with the greatest respect. Harindran Pakkom, a member of the same tribe, explained in a personal interview how respectfully and carefully they maintain the keni. He added that they do not use this water for bathing or washing and that they approach it barefoot. The keni system is an example of how water was traditionally conserved.

Figure 4: A Keni in a Kuruma hamlet

The Kurichiya and Kuruma communities are known for their traditional knowledge of ethnic medicines. Several herbs are used for primary health care and traditional healing practices. For example, Achappan Vaidhan, an octogenarian at Kattikkulam, Wayanad, is a tribal healer who belongs to the Kurichiya tribe. His healing practices are widely renowned inside and outside Wayanad. Kelu Vaidhyar, who is also from Kattikkulam, treats people using wild herbal plants. Both are famed healers who can treat all sorts of diseases with wild grasses and plants that they collect from the forests.

Tribes in Kerala have been marginalised, abused, and exploited because of their limited access to jobs, infrastructure, and education. In the past, they had sustainable lifestyles that were closely linked to the environment they lived in, and which ensured their economic independence. These tribes are storehouses of vast ecological knowledge—of local flora and fauna, edible plants, ethnic medicines, herbs, animals, rivers and streams, migratory birds, patterns of animal behaviour, changes in the season and climate, and much more. The potential loss of tribal culture and languages will have a lasting impact in the way we look at and perceive the environment around us.

The concept of the Daivappura and its centrality in the lives of the Kurichiya and Kuruma tribal communities

The daivappura (Abode of God) is central to the spiritual life of the Kurichiya and Kuruma communities, and its significance extends beyond the spiritual to the social. It is a powerful force in maintaining decorum and law and order in Kurichiya and Kuruma settlements, and its presence enforces strict vegetarianism within the premises of the muttam. The deities worshipped by these communities include Bhagavathi (also referred to as Thampuratty, the goddess of the hamlet), Athiralan, Karimpilli, Moonammandaivam, Vettakalan, Kali or Mariamma, Kuttichathan, Ormoonalan and Pullamottan-Perumal. Gulikan and Malakkari are considered the highest among gods, though this may vary from hamlet to hamlet. Ancestors or nikalayamuny are also worshipped, and Komaram is their oracle. These days, the communities also frequent the temples of Vishnu, Ayyappan or Sastha, Siva, and Muruga, and celebrate major Hindu festivals such as Thulampathu, Theyyam Thira, Puthari, Onam, and Vishu. Kurichiyas give offerings such as alcohol and roosters to deities like Gulikan during particular times like Karkkida Pathinaalu, which falls on the 14th day of the Malayalam month of Karkkidakam.

Figure 5: The daivappura in the Kuranjuvayal Kuruma settlement in Pulpally Panchayath, Wayanad

The daivappura is a centre of sanctity in the hamlet, and plays an important role in the daily life of the community. In each hamlet, there is a person—the eldest male member called karanavar or porunnor—who is authorised to perform religious rites. The daivappura holds a supremely powerful position in the hamlet, as it is believed that the whole universe is the abode of god, but that god resides in the daivappura as a neighbour, as if the god is living within the community and looking after them. Special rites are performed for the deity, and a hunt is conducted as part of the yearly festival called Uchal. A share of everything is given to the daivappura, which is to say, to god—the flesh of animals, alcohol, and bananas. Human qualities are ascribed to god in a manner that is very distinct from practices in structured religions.

Figure 6: Lamp lit inside the daivappura

Figure 7: Special rites are performed in the courtyard of the daivappura during the Thulam Pathu festival

All significant events in the hamlet are performed in the daivappura courtyard. The karanavar or porunnor of each hamlet is in charge of the premises. He cleans the premises every day and lights the lamps every evening. At festivals, lamps are lit in the daivappura, inviting the blessings of ancestors and gods. Women are forbidden from entering the interior of the daivappura, but they can watch and participate in the rituals. Daivam Kanal (‘Seeing the God’) is a unique ritual performed on occasions deemed appropriate by the karanavar of the hamlet. A performer, considered to be the incarnation of god, performs this ritual and there is chanting and worship of Thampuratty. The karanavar brings forth the concerns of community members to this ‘god incarnated’, and the performer gives answers and solutions while in a trance. In this way, they invoke Thampuratty, the clan deity, and seek her blessing. Rituals to pay respect to ancestors are also part of the ceremony. Slight variations in the rituals can be found among various colonies of the same tribe.

During the Uchal festival, lamps are lit in front of the daivappura. Throughout the night, elders, children, and women worship their god and make offerings. Traditional songs are sung, accompanied by musical instruments called thudi and kuzhal (musical instruments made out of bamboo), which are exclusive to the Kurichiya and Kuruma communities. Dancers in a trance perform before the daivappura. At the end of the performance, some dancers lose consciousness in a state of ecstasy and fall to the ground. The festival ends with the Daivam Thullal, performed by karanavar before the daivappura. The belief is that the god will be pleased by their offerings and worship during Uchal if the rituals are conducted properly; if not, the god will get angry and curse them with disease, death, or other afflictions.

As mentioned earlier, the daivappura is also considered the abode of ancestors. Koottathilkoottuka is a ceremony to call the spirits of the dead to the daivappura. It is performed by the karanavar. In every hamlet, along with the daivappura, trees are worshipped and are never cut, as they signify the presence of god in the settlement.

The daivappura is the spiritual heart of the Kurichiya and Kuruma colonies. The folk and religious customs of these tribal communities, and their cultural festivals, are unique and distinct from dominant Hindu religious practices, worship, and rituals. Daivappura is one such central and distinct element of the Kurichiya and Kuruma communities.

Significance of this study and the documentation

Documenting these indigenous cultures and rituals is important as they are on the verge of oblivion. Documentation, interviews, and photographs are means of preserving this knowledge for future generations. This study is an attempt to highlight the wisdom and cultural practices of these tribes. Indigenous knowledge and practices concerning worship, agriculture, food habits, and the preservation of natural resources can be of great use in the present world. The wisdom of tribal communities can prove crucial in building a more sustainable world—there is much to learn from how they live in harmony with nature.

References

Ayyappan, Ayinipalli. 1965. Social Revolution in Kerala Village: A Study in Culture Change. Bombay: Asia Publishing House.

Balakrishnan, E.P. 2004. ‘Economies of Tribals and Their Transformation- A Study of Kerala.’ PhD thesis, Pondicherry University, Mahe.

Binu, Paul P. and Rajasenan, D. 2013. ‘Income, Livelihood and Education of Tribal Communities in Kerala–Exploring Inter Community Disparities.’ PhD thesis, Cochin University Of Science And Technology.

Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner. 2011. Census of India 2011. New Delhi: Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India.

George, J. 2007. ‘Socioeconomic Impact of Job Reservation: A Comparative Study of the Christian Malai Arayans and other Hill Tribes in Idukki and Kottayam Districts of Kerala.’: PhD thesis, Mahatma Gandhi University, Kottayam.

Gopala Panikkar, T.K. 1900. Malabar and its Folk. Madras: G.A. Natesan and Co., Printers.

Johnny, O.K. 2001. Wayanad Rekhakal. Calicut: Pappion.

Joseph, K.V. 2002. ‘Migration and the Changing Pattern of Land Use in Malabar.’ Journal of Indian School of Political Economy, 14 (1): 63–81.

Kumar, B. Pradeep. 2013. ‘Financial Exclusion among the Scheduled Tribes: A Study of Wayanad District in Kerala.’ PhD thesis, M G University, Kottayam.

Logan, William. 1887. Malabar Manual, vol. I & II. Madras: The Superintendent, Govt Press. Reprinted 1951.

Nair, G.S. Unnikrishnan J. 2016. ‘Traditional Wisdom in Harvesting Water.’ Traditional and Folk Practices 2–4 (1): 50–53.

Nair, Madhavan, K.G. 1998. Wayanadum Pazhassithampuranum. Sulthan Bathery: San Georgia Offset.

Nair, Rao Bahadur C. Gopalan . 1911. Wynad: Its Peoples and Traditions. Madras: Higginbotham & Company.

Panchayath Level Statistics – 2011, Wayanad District. Kerala: Department of Economics & Statistics, Government of Kerala, http://www.ecostat.kerala.gov.in/images/pdf/publications/Panchayat_Level_Statistics/data/2011/pswayanad2011.pdf

Ramachandran, Bindu. 2004. ‘Fertility Concept in a Ritual an Anthropological Explanation of “Pandal Pattu”.’ Studies of Tribes and Tribals, 2 (1): 19–21. DOI: 10.1080/0972639X.2003.11886499

Scheduled Tribes of Kerala: Report on the Socio-Economic Status (Draft). November 2013. Scheduled Tribes Development Department, Government of Kerala.

Ravindran, T.K. 1976. ‘The Kurichiya Rebellion of 1812.’ Journal of Kerala Studies vol. 3 September December 1976, Part III & IV.

Syam, S.K., and Phil, M. 2016. Kurichiya Tribe of Kerala-A Phonological Study. Language in India 16 (1). ISSN 1930-2940

Shyma, T.B. and Devi Prasad, A.G. 2012. ‘Traditional Use of Medicinal Plants and its Status Among the Tribes in Mananthavady of Wayanad District, Kerala.’ World Research Journal of Medicinal & Aromatic Plants 1 (2): 22–26. ISSN 2278 - 9863

Thomas, Madathilparampil Mammen, and Richard Warren Taylor, eds. 1965. Tribal Awakening: A Group Study. No. 11. Bangalore: Christian Institute for the Study of Religion and Society.

Thurston, Edgar. 1909. Caste and Tribes of Southern India. New Delhi: Cosmo Publications.

Vaisakh, B. 2017. ‘Tribal Settlement in Wayanad: Architecture and Design.’ International Journal of Civil Engineering and Technology 8 (5): 1319–1320.