The last functioning bhishtis of the old city of Delhi operate from a makeshift workshop, behind the Mushtaqeem Chai Stall

It is by no means an easy task to locate the corner from where the last functioning bhishtis (water carriers) of the old city of Delhi operate. Hidden behind a tea stall (Mushtaqeem Chai Stall) near the eastern staircase of the stately mosque, Jama Masjid, it is lost amidst the teeming crowds emanating from the adjoining Meena Bazar. The makeshift workshop can be recognized by the traditional goatskin water bags called mashaq that adorn the two adjacent walls of this corner.

The last bearers of the forgotten mashaq of Old Delhi are three brothers: Mohammad Jameel, Khaleel and Shakeel. Not originally from Delhi however, they hail from a family that belongs to the bhishti community and has served as water carriers for generations. The brothers came to Delhi with their father as young boys some 40-45 years ago from Moradabad, a city in western Uttar Pradesh, and have now worked here long enough to call this city their own. The well that they draw water from is part of the dargah complex that houses the shrines of two famous Sufi saints of Delhi, Hazrat Hare Bhare Sahib and Hazrat Sarmad Shaheed.

The well the bhishtis draw water from is part of the dargah complex that houses the shrines of Hazrat Hare Bhare Sahib and Hazrat Sarmad Shaheed.

As one of the oldest surviving professions of Delhi that now faces extinction, these bhishtis are like breathing relics of a world gone by. Today, the idea of a man carrying water in an animal skin bag from a well sounds unusual. While not too long ago, this same man was a figure intrinsic to the social landscape of the city of Delhi.

One of the oldest surviving professions of Delhi

Both under the Mughals as well as the British, bhishtis were indispensable for they were employed by the State to provide water to soldiers. Rudyard Kipling’s poem, Gunga Din (1890), despite its racist language, underscores how essential the bhishti was to providing most basic sustenance to British troops in India’s 'sunny clime'.

When the sweatin’ troop-train lay

In a sidin’ through the day,

Where the ’eat would make your bloomin’ eyebrows crawl,

We shouted ‘Harry By!’

Till our throats were bricky-dry,

Then we wopped ’im ’cause ’e couldn’t serve us all.

It was ‘Din! Din! Din!

‘You ’eathen, where the mischief ’ave you been?

‘You put some juldee in it

‘Or I’ll marrow you this minute

‘If you don’t fill up my helmet, Gunga Din!

.

.

.

When the cartridges ran out,

You could hear the front-ranks shout,

‘Hi! ammunition-mules an' Gunga Din!

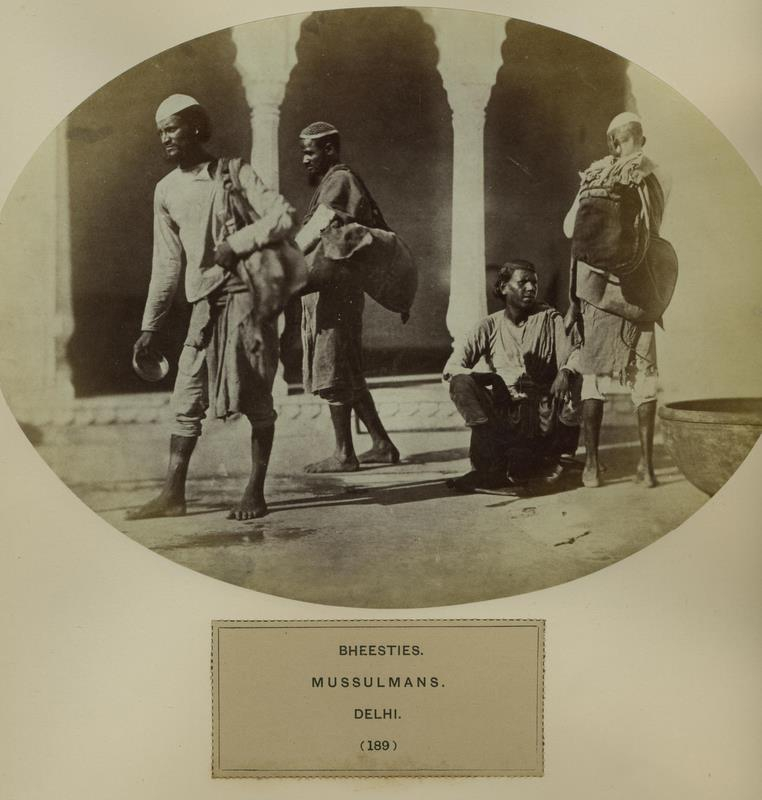

From The People of India (1868 to the early 1870's), by W.H. Allen, for the India Office. Source: Columbia University

As the poem closes with Gunga Din losing his own life as he saves the life of the narrator, the poet hails him as the ‘better man’ amongst the two for not just saving his life but also for being the carrier of the ‘source of life’, for quenching his thirst when he was 'chokin’ mad' with it, so much so that, he imagines him 'Givin’ drink to poor damned souls' in the afterlife too.

In fact, the very word ‘bhishti’ comes from the Persian word ‘bahisht’, meaning ‘paradise’. Water was always considered precious, being fundamental to human existence and the man who brought it to one's door was akin to someone whose place in Paradise was a given, Paradise being a place of cool streams where one ceases to thirst both physically and spiritually.

All the nearby tea stalls brew their tea in the water delivered by the bhishtis.

Curiously enough, the three brothers continue to pursue a profession that has become almost entirely redundant, replaced by technologically more feasible access to water. One explanation that Mr Jameel offers for their tenacity is that they are khaandaani bhishtis, their forefathers having served as water carriers for generations and this is all that they have inherited. Mostly illiterate, unskilled and poor, other livelihood options such as daily wage labour are equally unappealing to them. He also likes to believe that this is a virtuous job, that to ‘quench the thirst of the needy’ is a noble deed, and he is bitter over the reality that people don’t give it its due reverence. He proudly narrates the traditional folklore of the bhishti community whereby they have the title ‘Abbasi’ and that testifies to their former glory. According to legend, Hazrat Abbas was a water carrier of heroic valour. During the battle of Karbala, he galloped towards the injured, dying and thirsty warriors of Hussain, Prophet Muhammad’s grandson, and was attacked with arrows that punctured his water bag. Another saga is that of Nizam Saqqa, the bhishti who saved the life of a drowning emperor Humayun, was given kingship for a day in reward and issued the legendary leather coins.

Bhishtis are often paid to provide water in public spaces for cleaning.

Mr Jameel, who sees himself as heir to such valiant traditions laments that they are not respected anymore. According to him, bhishtis were a respected community during the Mughal period as well as the British era. As they started working under government organisations of independent India, such as the municipal corporation which employed them along with bhangis (sweepers) to clean naalis (drains), coupled with their receding relevance, they started being associated with the lower castes and began to be considered ‘unclean’. Besides, 'Ab zamana badal gaya hai', he complains, deprecating in general the loss of tehzeeb among the younger generation. While it is true that bhishtis were given more importance earlier in keeping with the significance of their services, they did however always belong to the lower rungs of society. Some of the old pictures of bhishtis found in British archives are titled, ‘Giving a customer a drink without physical contact’, very clearly indicating their class and caste positioning in society. Caste differences, though codified in Hinduism, were very much a part of Muslim households too in the old city. Divisions were occupational (this is sometimes referred to as the biradari system, though the term is also used to refer to kinship relations), and communities were divided into high (shareef) and low (razeel) castes accordingly. Bhishtis today feature on the list of OBCs (Other Backward Castes).

The last practitioners of this profession are now relegated primarily to delivering water to street vendors

The last practitioners of this profession in the city of old Delhi are now relegated primarily to delivering water to the nearby street vendors and hawkers. All the food cooked and all the drinks like sharbat (sherbet) prepared close by use the water from our well, Mr Jameel informs us. They also provide water to travellers, or at times a person will pay them for distributing drinking water for free to thirsty passers-by as charity. Sometimes they are sought by nearby houses when there is a scarcity of water and they can also be hired to provide water for cleaning shops. Summer usually means more work, as they are often asked to do chhidkaav (water sprinkling) to assuage the sweltering heat of the dry and dusty city, or to fill water coolers in market shops, but winters can be very hard. Festival seasons also translate into more opportunity but other than that, work is scarce and earnings are meagre. A mashaq can carry about 20-30 litres of water which fetches a paltry sum of 30-40 rupees. In the face of competitors like refrigerated water trolleys, tankers, electric motors and pumps, plastic water bottles etc, a ‘good’ day’s earning might amount to 200-300 rupees, barely enough to make ends meet.

Bhishtis are often asked to do chhidkaav (water sprinkling) to assuage the sweltering summer heat

Frustration arises as a consequence, and their children have taken to other professions, unwilling to pursue a physically taxing job that has barely any returns. Rashid, the eldest son of Khaleel does help his father out but hopes for a better future for his three younger brothers, two of whom are learning the skill of welding.

While the descendants of the native bhishtis of Shahjahanabad have long taken to other professions such as dealing with spare motor parts in Kabadi Bazaar, bookbinding, etc., their name is still tagged to the neighbourhood that their ancestors originally inhabited. The winding narrow galis (lanes) of old Delhi are famous for having been named after the professions of the biradaris that occupied them. And in all its right exists Sakkewali Gali, the mohalla that was home to the bhishtis of the old city and is now occupied largely by the bawarchi community (chefs).

Slowly vanishing from collective memory, bhishtis of Shajahanabad once performed important domestic functions and an attempted recovery of their history provides fascinating glimpses into everyday life in the old city. They catered to both public and private spaces, delivering water to shops and homes alike for drinking, cooking, brewing tea, washing clothes and utensils etc.

Though their relevance, domestic and otherwise, began to be questioned with the establishment in 1862 of the British civic administration in Delhi, which eventually went on to introduce water pipes and taps in the lanes of Delhi, making water (drinking and otherwise) very accessible, there are household memories that recall the services of bhishtis till as late as the 1960s.

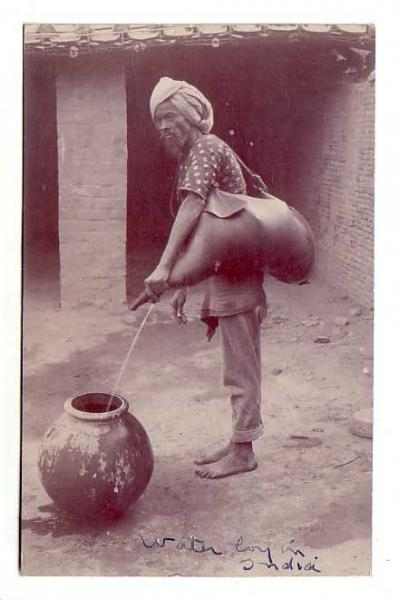

Photograph from 1910. Source: Columbia University

A resident of the old city all her life, Ms Farhat Ara belongs to a family of the Jootewali biradari who have been dilliwalas ('Delhi-ites') for generations. She shares a very telling incident from her childhood in the 1960s: a bhishti would deliver water to the house of her ustanji (female teacher) in Gali Jootewali. Interestingly, the man would only enter the house with his face covered with a cloth and would then pour the water into big ghadas and matkas used for storing water, a habit that the children found very amusing. Further, the money that he was paid was given to one of the children by the ustanji who herself never came out of the inner quarters of her house in his presence, in accordance with the purdah tradition that most women observed. However, an added reason for the bhishti covering his face could very likely be that he belonged to a class for whom it would not be befitting to catch sight of a woman from a shareef household even by mistake.

Nevertheless, like most other professions in old Delhi, they had established relationships with specific households, in contrast to the alienation that a modern urban landscape entails. For instance, for us today it may seem intriguing that people were particular about which well’s water they drank. Every mohalla would have its own well and bhishtis delivering water would often announce which well they had drawn it from as they made their presence felt by beating their tambe ke katore (copper tumblers) against each other. Wells were part of almost every religious site (mosque, temple, gurudwara), and elite households had private wells, while every mohalla had its local well.

The well of the dargah complex is the only one still being used by the bhishti community.

Initially handpumps were built over these wells to make water more accessible but eventually wells went out of use. Some dried up while others became unusable. For instance, a well in Katra Shahanshahi was used till as late as the 1970s but ultimately was contaminated by a leaking sewage pipe, making its water non-potable, so it had to be abandoned. While Mr Jameel’s claim that the well of the dargah complex is the only functioning well left in the old city may be disputed, it really is the only well that is still being used by the bhishti community. The well owes its maintenance to the municipal corporation, which cleans it every six months.

Sohail Hashmi, who has written and lectured extensively on Delhi's heritage, and is a former resident of the old city, recalls going as a child in the late 1950s on visits to his phupho (uncle) who lived in Farashkhana, a Muslim-dominated locality in Old Delhi. His aunt specifically called for burme ka paani, water from a handpump attached to the local well of the mohalla. A bhishti would then deliver from the specified handpump attached to the well, which was known to have meetha paani (sweet water). He fondly remembers her saying, ‘Bachcho ko nalke ka paani pilayenge?!’ ('Would we make the children drink tap water?!'). Therefore, interestingly enough, in many households, municipal tap water was still not considered a ‘good enough’ source of drinking water; people would prefer traditional wells. Tap water was instead made good use of when washing clothes, utensils, vegetables etc.

Fixing straps onto the mashaqs: mashaqs are very expensive, so bhishtis take care of them to make them last

The mashaqs that Mr Khaleel use are made up of goatskin and are usually very costly ranging within 2000-2500 rupees, depending on the quality and durability of the pouch. Mr Khaleel is seen above fixing the strap of his mashaq in his workshop. Considering the upsurge of violence triggered by incidents of cow slaughter since 2015 in India, a question that comes immediately to mind is, what about Hindu households in the old city that didn’t consume meat, wouldn’t this animal skin be considered ‘impure’? Mr Hashmi provides an answer; most of the Hindu households of the old city did in fact consume meat. So the material of the mashaqs was not a significant issue. As for pure vegetarians, such as Jains, water was delivered at their homes in matkas or ghadas. It is striking that it did not become a matter of communal discord at all. Perhaps we could learn something from the erstwhile dilliwalas.

Another interesting conception that the bhishtis bring to the fore is the commodification of water. Today the idea of buying a bottle of water is the most ‘normal’ of things, whilst barely a generation ago, water, which is the ‘source of life', was not something that one ‘sold’. The bhishtis were charging for their services, not for water. It was socially accepted that water, which is fundamental to human existence, was something you didn’t deny even your ‘enemy’, and families of the old city would often keep matkas of water outside their homes for thirsty travellers. Historian of Delhi Professor Narayani Gupta recalls that the sale of water was initially so inconceivable that people would often joke about buying air next. Perhaps that joke has become a living reality, now as we read about people from Beijing buying Canada's fresh air.

So with the acceptance of the imminent disappearance of the occupation of the bhishti in Shahjahanabad, my conversation with Mr Jameel came to a close. We sat in silence for some time in the dargah complex, brooding over our cups of tea, brewed in the water drawn from the very well that we were just talking about. And as we mulled over the strange end of most human effort in amnesia, we could hear a famous Sufi song (originally sung by Yusuf Azad Qawwal) playing in the background from a tiny box-shaped TV in the adjoining bookshop and it seemed to be mulling with us too.

Khaak ho jayegi har nishaani teri,

Khatm ho jayegi yeh kahani teri,

Chaar din ka tera maan samman hai

Maati ke putle tujhe kitna gumaan hai

(Loosely translated as, 'All trace of you will end in dust, This story of yours will come to a close, A few days of glory to call your own, Oh toy of clay, how vain your dreams!')