This article was a direct result of Sahapedia's collaboration with the Conference on Handloom and Handicrafts in India, held in Chirala, Andhra Pradesh, November 2018.

All quotes in italics are from an interview with Suresh Vankar, November 2018.

History is not always written, it is often borne forward in stories that are repeatedly told, generation after generation. The thangaliya style of weaving, practiced today only in a handful of villages in Gujarat, finds its origins in just such a story.

Among the Dangasias in Gujarat’s Surendernagar district, there is a legend that goes back some 700 years. There once lived a family of three brothers among the Bharwaad shepherd community in Saurashtra. The middle brother fell in love with a girl from the Vankar weaving community. Their families vehemently opposed their marriage because of the caste difference, but the couple were stubborn in their love. Ostracised by their neighbours, disowned by their families, and with no source of income to sustain themselves, the couple lived in great hardship. The boy’s family was saddened to see him struggle, and offered to provide grain and sheep wool to him if, in exchange, he would weave shawls out of the wool for the shepherding community.

From then on, the young couple made shawls and cloth for the Bharwaads, weaving unique daanas (beads made out of thread) into the fabric. The couple’s offspring went on to form the Dangasiya community (the word Dangasiya is derived from the word dang, meaning a shepherd’s staff). The Dangasiyas continued to develop the unique thread-beading technique that they called thangaliya.

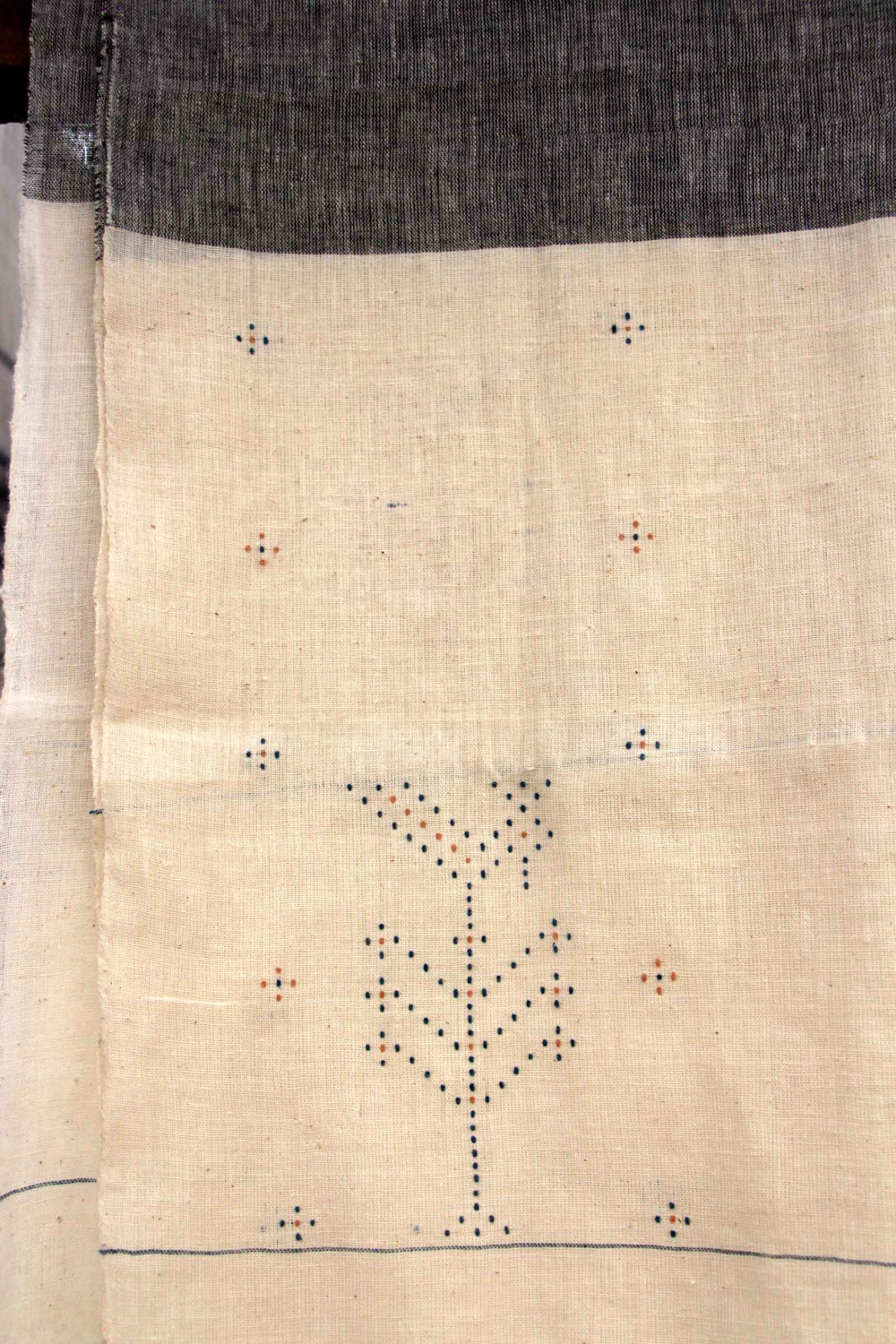

Today, thangaliya is used to describe a weaving technique where patterns are woven into the fabric by arranging raised dots of thread, which are visible on both sides of the fabric. This technique requires skill, nimble fingers, attention to detail and, of course, patience.

Suresh Vankar is a weaver from the Kutch region of Gujarat. He hails from a family of thangaliya weavers in Adhoi village. In fact, thangaliya weaving is the major occupation in his village. When I went to meet him, I found him sitting at his loom, taking a break from sending the shuttle flying across the taut warp with dexterity and ease. It was hypnotising to see a beautifully patterned cloth slowly form on the loom. He was weaving a dupatta with vermillion borders and a black body. Carefully placed dots formed simple and elegant patterns on the cloth. Each little dot was woven individually, and eventually a motif was transferred from the weaver’s mind onto cloth, with no help of paper and pen.

The thangaliya weaving technique was originally used in creating a piece of cloth that the men wore as shawls while out shepherding, and women wore wrapped as skirts. Bharwaads in the Wankaner, Amreli, Dehgam, Surendranagar, Joravarnagar, Botad, Bhavnagar and Kutch area wore these textiles.[1] Thangaliya products reflect the historically symbiotic relationship of the Dangasiyas with the Bharwaads. The Bharwaads provided wool and grain and any overhead costs, and the Dangasiyas wove for them garments in return.

“In the past, we wove cloth for the women of the Bharwaad community—their ordinary everyday clothes, their wedding trousseaus, and a special cloth for the widows. We most commonly wove regular chaniyas, which the women of the Bharwad community wore over their skirts like a half-saree. Nowadays we weave stoles, sarees, mufflers, duppattas and garment material. The traditional weaving that we do is still being continued. Usually the older women of the community still buy it. There is a long-standing tradition that when somebody’s husband passes away, the widows are given a piece of black cloth known as prerana, we still weave that, and it is only made in Adhoi. We also continue to weave heavily designed wedding garments, the demand for that is always there.”

Although thangaliya weaving was traditionally done using native sheep wool, known as gheta, and occasionally indigenous cotton, these days the weavers use acrylic thread, merino wool, mulberry and eri silk, sourced from outside their native region, usually Ahmedabad and Bhuj.[2] Gheta wool was an assured resource for the Dangasiyas, a direct result of their barter-based relation with the Bharwaad community. The wool was hand-spun, hand dyed and hardy.

“When I have the time, I dye the cotton myself before weaving, but it takes a while to dye. Usually, I outsource my dyeing to dyers in Kutch, like Kheengar Singh Kaka, who uses natural dyes. This piece I am weaving right now has been dyed by him.”

With the introduction of machine-made acrylic yarn, weaving cloth became a cheaper process. When cheap printed cloth and readymade products entered the local markets, the Bharwaad community shifted its patronage away from thangaliya weaving which was time-consuming and therefore comparatively expensive.

The thangaliya weaving community has had to turn to new alternatives to sustain their weaving practice, incorporating acrylic wool and machine-made yarn. They began to use cotton more extensively because cotton products could be sold in newer markets catering to larger customer bases. Eventually, thangaliya weaving came to be most commonly done in cotton, with very few weavers remaining today who continue to weave with gheta.

“The products we sell are priced according to the amount of design they have on the body, along with the number of days it takes to weave them. For example, a saree is expensive; it takes anywhere from 10–15 days to weave, sometimes even a month. Stoles and dupattas sell for lesser; they take only a day or two to weave. It is a long and tedious process to weave thangaliya designs.”

For generations, weavers in and around Surendernagar have been weaving out of their homes. Thangaliya has always been a household craft tradition. The women of the household assist in tasks like cleaning the wool, preparing the yarn, dyeing, making bobbins and warping the loom, while the actual weaving is done by men of the household.

Warp and weft are the two basic components used in weaving to turn thread into fabric. Warp refers to the longitudinally arranged threads held stationary on the frame of the loom, while weft refers to the latitudinal thread that is drawn through the warp by inserting it over and under alternate threads of the warp. The warp is created using a strong yarn that allows it to withstand the stress and high tension during weaving. A loom requires 3,200–4,000 warp threads for a saree, 1,800–2,000 warp threads for a dress material and 1,200 warp threads for a stole.[3] It takes an entire day to complete the laying out the warp on the loom.

“The whole process of producing a thangaliya cloth is done largely manually. In Adhoi, women share in our work, without them there would be no thangaliya products. The women of the village put in a large chunk of work in the production process, that is how we can successfully keep weaving. They make the taana (warp) for the loom, they make the bobbins for our shuttles, and those are the most integral elements of weaving. Women also make the designs that we weave onto the cloth, some of them weave too.”

The looms don’t have the traditional warp beam. Instead the yarn hank gets knotted to a pole from which the yarns are connected through the head shafts to the cloth roll at the weaver’s end. Once the warp is laid out and the bobbins are readied by the women, the men begin to weave.

Every weaver’s home is equipped with a traditional pit loom on which the men weave. A pit loom is a small and simple loom that is installed in a pit. The weaver sits with his legs in the pit and operates the loom using two foot-pedals. This leaves the weaver’s hands free to do the daana work, which requires concentration and precision. A traditional pit loom is two feet wide, and due to this constraint in the width of the cloth produced, the cloth produced is usually 20m x 2m. This cloth is then cut into two parts and stitched together to form a 10m x 4m shawl.[4] The standard measurement of a thangaliya shawl is 10m x 4m.

The fabric for thangaliya is usually constructed in a plain weave. In plain weave, the warp and weft are aligned so they form a simple criss-cross pattern. Each weft thread crosses the warp threads by going over one, then under the next, and so on. The next weft thread goes under the warp threads that its neighbour went over, and vice versa.

Motifs are woven into the fabric while still on the loom. The tiny dots that are so unique to thangaliya weaving are created using an extra thread, the technical term for which is ‘extra weft’. Individual dots are created by tightly wrapping a small length of contrasting coloured thread on to a pre-decided number of yarns. The position of the extra weft dots on the fabric is based on the motif. The weaver uses his thumb and forefinger to delicately twist the extra weft thread on to the warp threads and then levels it with the rest of the fabric. This ensures that the dots look as if they are integrated into the weave of the cloth. After having completed the required dots across the warp width, the ground weft is inserted, the shed is changed and the pick is beaten in.

These dots, arranged geometrically, give an illusion of beads embroidered on cloth. The emphasis is on basic shapes like circles, squares, triangles and rectangles. Thangaliya motifs are largely inspired by the weaver’s religion, scenes from everyday life and natural surroundings.

The most common motif is the ladwa, which refers to the laddoo. Other recurring motifs are the mor (peacock), mor pag (feet of peacock), ambo (mango tree), khajuri (date palm tree), naughara (new house), bajariya ni zhaadavi (the bajra plant), bushes, leaves, and a combination of these to form more complex designs.

Traditional thangaliya weaving followed a certain colour palette—a black base with red borders and designs composed in white dots. Some motifs are created using fixed colours; this is usually the case when the motifs are traditional ones that have been handed down the generations. The zalawadi motif is made with only white and maroon threads, while halari and bhadar are made with colourful threads.

“There is a big difference in the work done in Adhoi when compared to thangaliya done in the other villages. This difference is the thread used to create the dots. In Adhoi we use very thin and delicate cotton threads wound many times over to create the little dots, whereas in other villages they use thicker cotton threads wound lesser number of times to create the little dot. Nowadays, these other villages have also started making stoles and sarees like us. In Adhoi we have a special design that is only made by us and by no other village, and the design is made on kaala-cotton. We make the kaala-cotton cloth ourselves; it is a greyish black naturally coloured cloth made of organically grown indigenous cotton. This is Adhoi’s specialty, you will find it nowhere else. I have also begun weaving sarees out of kaala-cotton and they sell very well.”

Based on the colours of the cloth, the colours of the daanas, the density of the motifs and designs, and the utility of the cloth, traditional thangaliya cloth can be categorised in the following ways:[5]

Ramraj: Heavy daana work done in bright colours such as maroon, green, yellow, pink, orange and white. The cloth is black with horizontal maroon lines. The borders sometimes have zari ornamentation.

Charmalia: The warp of the cloth is both maroon and black and the weft is black. The daanas are mainly white, and occasionally maroon.

Dhunslu: Dhunslu is usually worn by older women. It has very little daana work. The base is black and the daanas are either maroon or white.

Lobdi: It is the cloth used as a head covering. The base is maroon with white daanas.

With the passage of time, newer designs and motifs have come into use, incorporating symbols and images of modernity and urbanisation, such as aeroplanes, towers, bungalows, etc., alongside traditional motifs. Suresh Vankar says that another factor that has accounted for newer designs are the Government-run weaver training centres, where weavers from villages have learnt to make newer motifs and designs using the traditional technique.

“In 2013 I graduated from the Kala Raksha Vidyalay in Kutch. I also sent my wife to the Government-run weavers training centre, and now she makes the designs and I weave. In fact, she is my boss (laughs). It was there that I learnt how to combine colours, create newer designs and cater to the current market demands. I also learnt how to make pieces that are not too design heavy so that they are affordable, and pieces which are heavily patterned. Thus, I cover a wide customer spectrum.”

As Vankar explains, the customer base for thangaliya weaving has indeed changed and grown. Thangaliya was woven primarily in black sheep wool or camel wool to create shawls and dhablas (blankets and garments like galmehndi, dhunslu and charmalia) for the Bharwaad community, and did not have any urban market until about a decade ago. They now sell to a slightly larger market, in Delhi and Ahmedabad, and make some sales through Khamir, an organisation working with the crafts, heritage and cultural ecology of the region of Kutch in Gujarat. One surprising customer base is foreigners.

“Khamir is good for our business because apart from finding us customers, they also give us exposure by bringing us to events and fairs across the country. Kala Raksha Vidyalay was also good in terms of exposure. As a part of graduating, we had a fashion show, and there were spectators from abroad, a new customer base.

“Foreigners wear well-tailored minimal clothes, with light designs on them. I like their clothes, and want to make material for those kind of clothes. It is my dream to make thangaliya for everyone. I have woven things ranging from a small handkerchief to a heavily patterned saree. I want a day to come where everybody can afford to wear thangaliya work. I must tell you, one time I had an American woman customer give me an interesting tip—to make thangaliya for blind people, who can then read patterns on the cloth with their fingers, just like Braille. I am soon going to make just that to spread some joy among the blind.”

The Dangasiya weavers live and weave in eight talukas and 26 villages in and around Sundernagar district. It is truly a tiny community. Fortunately, wider demand and recognition of thangaliya appears to have sustained weaver families so far, and the craft continues to attract the younger generation even today.

“In Bhujodi and Kutch, people recognise my designs and help me outsource it to other places. Among those who weave, there are the older weavers, particularly those who only wove for the Bharwaad community. In my family, we have been weaving for generations, but I am the first generation catering to communities from outside. My younger brother, my father, my uncle—all of them are weavers. Now a lot more people have started weaving for modern markets; they usually work under another person, as employed weavers. I work on my own, and have a few weavers working under me. The younger generation from my village, it is surprising to note, have shown much interest in learning thangaliya weaving. They are not moving towards private or government jobs; they want to join the family business. They usually want to go to fashion and design institutes like NID and NIFT so they can learn newer designs and colours, and eventually sell it to foreign markets. The foreign market holds a lot of potential for thangaliya weavers. I am hoping to sell my pieces abroad too, eventually.”

Notes

[1] Devanshi D. Mehta, 'The uniqueness of Tangalia Weaving of Gujarat' (MA thesis, Department of Design Space, NIFT, 2017).

[2] Interview with Suresh Vankar.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Vandita Seth and Anitha Mabel Manohar, 'Tangaliya - The Lesser Known Textile Craft of Saurashtra Gujarat,' Fibre2Fashion.com, accessed November 22, 2019, https://www.fibre2fashion.com/industry-article/6923/tangaliya-the-lesser-known-textile-craft-of-saurashtra-gujarat.

[5] Ibid.