The year was 1948. India was participating as an independent nation for the first time in the Olympics. India had never won an individual medal at the Olympics—except Norman Pritchard’s brace of silver medals in 1900, but Pritchard was ethnically British. Amongst the 79 participants India sent to London in 1948, was a young wrestler from the village of Goleshwar in Satara district, Maharashtra. Khashaba Dadasaheb Jadav was 22 years old and hailed from a family of pehelwans (wrestlers) where he trained from a young age. His talent was spotted and his trip to England was sponsored by Shahaji II, Maharaja of Kolhapur. K.D. Jadhav finished sixth in the flyweight category, but gained valuable experience competing on the unfamiliar mat surface. Jadhav trained hard and returned for the Helsinki Olympics in 1952. This time he won bronze in the bantamweight freestyle category; the first ever individual medal won by an Indian at the Olympics. K.D. Jadhav returned to a hero’s welcome to his village and was felicitated in Kolhapur.

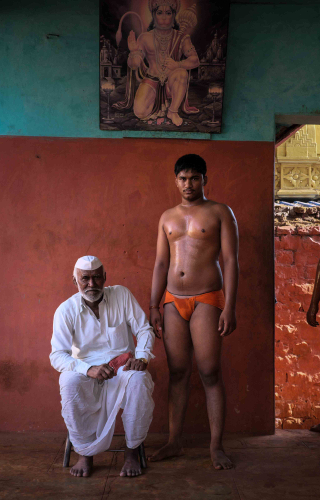

Kolhapur has a long history of kushti (wrestling) and has produced many noted wrestlers. The sport flourished during the reign of Chattrapati Shahu Maharaj (ruled 1894–1922), remembered for being a progressive ruler who brought about many social reforms. During this golden age, Shahu Maharaj built akharas all over Kolhapur and organized wrestling tournaments, inviting legendary wrestlers from across undivided India. Since then, Kolhapur’s wrestling culture has been dominated by Gangavesh Akhara, Shahupuri Akhara, Motibag Akhara and New Motibag Akhara. In each of these akharas, more than 70 wrestlers undertake taleem, or training. Hence, the akhara is colloquially also known as taleem.

Families aspire to send their children to the taleems from an early age. Daily life at a taleem is based on egalitarianism, strict discipline, healthy diet, high morals and ethical living. When a pehelwan completes his taleem, it brings high social status for the entire family. Many families in Kolhapur have a history in wrestling and they want to continue the tradition, irrespective of the high cost and sacrifices made. Though the fees paid to gurus are nominal, monthly expenditure on food and dietary supplements cost between 10 to 25 thousand rupees depending on the age and weight of the wrestler. During this period, trainee pehelwans are sustained by money sent from home. The agrarian economy acts as a lifeline for the sustenance of wrestling in this region. Most pehelwans belong to farmer families and their income depends on a good agricultural harvest. During severe drought in the Marathwada region, many pehelwans left training and returned home because their farmer parents were unable to support them. Even tournaments can get cancelled during years of bad harvest.

However, kushti has seen a shift in fortune in the last decade. Renewed interest in the sport was triggered after Sushil Kumar won bronze and silver medals in consecutive Olympics (2008, 2012), and Yogeshwar Dutt won a bronze medal (2012 Olympics). Following the male wrestlers, Sakshi Malik won a bronze medal at the 2016 Olympics, inspiring a new generation of female wrestlers. Indian wrestlers—both male and female— have also won numerous medals at the Commonwealth Games and Asian Games which has brought much prestige to the sport. The success of the Phogat sisters was featured in the super-hit movie Dangal and girls now see wrestling as a viable career option. This has come as a welcome change within the sporting community and has received support from parents, sponsors, gurus, coaches and male wrestlers. Kolhapur’s taleems have now opened up to female grapplers who undergo training on the same level as boys.

The rise in popularity of the sport has also brought in increased prize money at tournaments. Some reputed wrestlers get paid for only participating in the tournament. Politicians have started sponsoring wrestling tournaments to connect with the masses and influence their vote banks by exploiting the popularity of the sport. Pursuing a career in wrestling—other than the prestige and fame—has also opened up job opportunities, particularly in the police force. In the government sector, wrestlers can also get jobs through the sports quota. Many wrestlers go on to become coaches working with bodies like the Sports Authority of India or the Wrestling Federation of India, or they independently run their own akharas.

Despite these changes, there is still a huge difference between training in a taleem and winning medals at international tournaments. The main reason is the difference in tactics, rules, training facilities and playing surface. Wrestlers practice on specially prepared soil in the taleems and the competitions held in villages are also held on open ground, but international tournaments are held on mat surface and follow a scoring pattern adjudicated by a panel of judges. Wrestling on soil is all about stamina and strength, because there is no time restriction. In comparison, wrestling on mat is all about tactics and speed because each round lasts only for a few minutes. Mats are expensive and not available for training. This is why wrestlers get less practice on mat, which affects their performance at national and international games where soil wrestling is not allowed.

In this photographic journey, I have documented the passion for wrestling I witnessed in the taleems of Kolhapur. I also got to explore the hinterlands and experience how the people of rural Maharashtra celebrate wrestling with fervour. The kushti tradition is still alive and thriving, and I hope in the future India will unearth many medal winners from the soil of its traditional taleems in Kolhapur.