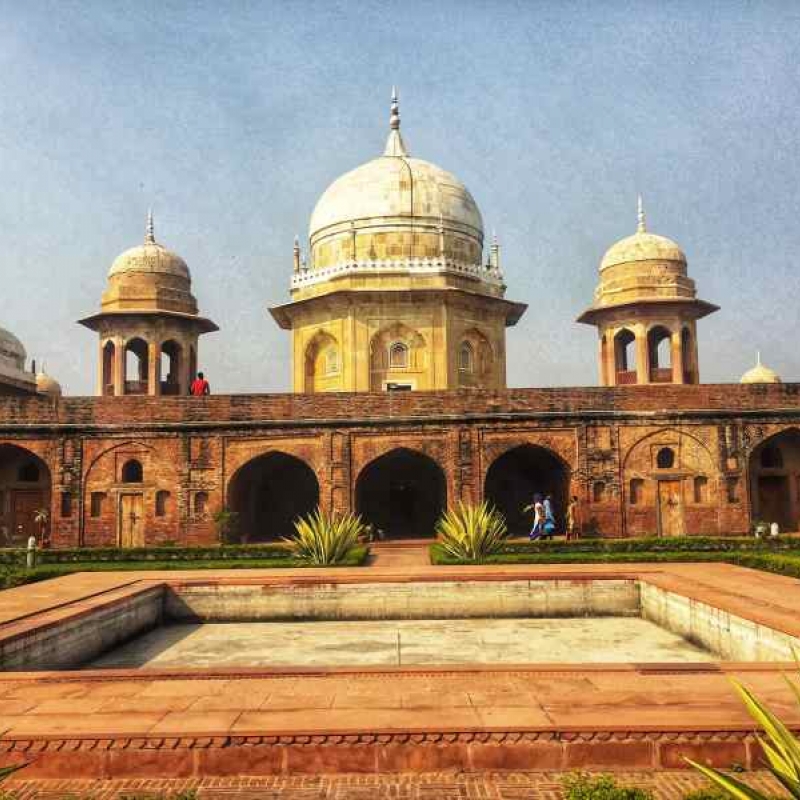

While some might have heard of Sheikh Chilli ke Lateefey of ‘air castles’ fame, not many know that there was once a seventeenth century spiritual master of the same name, and there is even a stunning tomb in Thanesar, Haryana, in his memory. We take a look at the tomb complex which is an interesting study in the development of Mughal architecture. (Photo courtesy: Vineet Bhanwala/IHW)

Thanesar is mainly known as the ‘land of the Mahabharata’ principally because of its twin city Kurukshetra, where the epic battle is said to have taken place, and the text of Bhagavad Gita composed.[1] However, unknown to many, there is a beautiful seventeenth century tomb tucked away here, which is often referred to as the ‘Taj of Haryana’. Sheikh Chilli ka maqbara (mausoleum) is a haunt for those interested in architecture. Not yet on the popular list of monuments to visit in India, this hidden gem is an ideal spot to visit and soak in the details of Mughal architecture without swarms of people or long queues.

Also read | Sanchi Stupa’s Contribution to Indian Architecture

Sheikh Chilli is said to have been a Sufi saint and a beloved teacher of Dara Shikoh, Shahjahan’s eldest son. This connection might explain this impressive monument, which houses two tombs, a madrasa (Islamic seminary), a masjid and a garden. British traveller Davis Ross, in his travelogues of 1881–82, ‘refers to him as “the author of some of the most popular moral tales, allegories, and ballad.”’[2] These are probably now the same popular Sheikh Chilli ke Lateefey/Kisse (loosely translated to ‘The Tall Tales of Sheikh Chilli’) for children. However, ‘Sheikh Chilli having any connection with Dara Shikoh's spiritual master is a matter of speculation by scholars. For all the grandmothers telling these funny tales, it is the comic potential in the stories that have kept them alive,’ says Manisha Chaudhry, Director, Manan Books, and an expert on Indian children’s literature. The famous proverb on ‘building castles out of thin air’ is credited to one of his stories. In fact, it is not uncommon to hear his stories being recounted around 1 April (that is, April Fool’s Day) since he is undeniably one of the most well-liked ‘fools’ in Indian literature, akin to Mullah Nasiruddin.

Architecture Through the Ages

While there is not much written on Sheikh Chilli, it’s said that he was a Sufi of the Qadiriya order, and his name could have been Abdur Rahim, also referred to as Abdul Karimor Abdur Razak. This is interesting, since Thanesar was mostly dominated by Chishti saints. The surname ‘Chilli’ is apparently a corrupted version of ‘Chehli’, which means 40 in Persian, reminiscent of the 40-day ritual of chilla, or fasting and solitude. His mausoleum and the surrounding complex have caught the eye of historians, who say that it presents an insight into the development of Mughal architecture. Sir Alexandar Cunninghum, the first Director-General of Archaeological Survey of India (ASI; during 1862–65) placed the tomb’s construction to around 1650. Many scholars have also attributed these two tombs to different saints and personages,[3] but the locals refer to it as the tomb of Sheikh Chilli.

Related | Sufi Shrines of Shahjahanabad

Writing about it, historian Catherine B. Asher said that the mausoleum complex does not ‘simply imitate earlier buildings or ornamentation, and their refinement suggests a patron of considerable wealth and taste’.[4] There are elements of different Mughal styles, such as the octagonal tomb, which continues from Akbar’s reign, similar to Shah Quli Khan’s tomb at Narnaul. The tomb and the adjacent mosque, situated in an elevated walled compound, are built of buff stone. The white marble dome sitting atop the sandstone structure is its distinguishing feature, as well as its placement in a charbagh (four garden) layout. The tomb in its central chamber has the cenotaph of Sheikh Chilli with marble arches and exquisite lattice (jaali) work around it. The smaller tomb is said to have been of his wife, and other graves those of family members.

Interestingly, according to ASI reports and those by Ross, the tomb had been converted into a gurudwara in the eighteenth century by some Sikhs, who even removed bits of marble to build a gurudwara in Kaithal.[5]Lt William Barr of the British Army found it in ruins during his visit to the Indian subcontinent in 1839. It was later reinstated by ASI.[6]

The Complex Elements

ASI excavations have revealed artefact spanning from the Kushan period (early first century) to Mughal era (sixteenth–nineteenth century), some of which are exhibited in the ASI museum within the complex. This is also reflected in the variation in architectural styles, such as the small Pathar Masjid (of red sandstone) close to the maqbara which could have predated the tomb, as it has some Khalji and Tughluq architectural features.[7] There is also a hammam (bath) on the northern side, assignable to the seventeenth century.

The quadrangular complex,within a fortified enclosure, has 12 chhatris (cupolas) and pavilions around it. Elevated on the ancient mound, the tall gateway opens onto a 174 sq ft marble-paved courtyard with a shallow tank surrounded by the garden. The galleries around the garden are believed to have functioned as a madrasa, believed to have received patronage from Dara Shikoh.

Also read | Tomb Complexes in Khuldabad

Scholar Subhash Parihar, who has researched the madrasa, wrote that ‘the tradition of attaching a madrasa to a tomb, usually that of the founder of the madrasa or a scholar who taught there, was as well established in India as it was in Turkey and Egypt.’ Ross, during his 1881–82 travels, saw both Hindu and Muslim children being taught Gurumukhi and Persian in this madrasa, which means it was still being used as a school then.[8]

At present, two galleries have been converted into Archaeological Survey of India museums, displaying artefacts discovered during the excavations of the Thanesar region, including a Mughal miniature painting of Dara Shikoh, many swords, seals, figurines and sculptures. Many of the exhibits—including Buddhist and Jaina sculptures from sixth to twelfth centuries, and even some shards of pre-Harappa pottery—were excavated from the nearby mound of Harsha-ka-tila (mound of Harsha) named after King Harshavardhana (606–647 CE)of the Vardhana or the Pushyabhuti dynasty, who started building his large empire from here. The name of the area, at the time, was said to be Sthanvisvara (Abode of God/Mahadev).[9] The presence of a sarai (resting house) close by, presumably built by Sher Shah Suri (1486–1545), indicates that the Grand Trunk Road (one of Asia’s oldest and longest roads) had passed by the tomb.

Sheikh Chilli’s tomb and the surrounding complex might not have received the kind of fame as other Mughal monuments of its time, but for architecture lovers and history buffs it remains a fascinating site.

Did You Know?

- The tomb’s style, specially its white bulbous dome resting on an elongated drum are characteristic of Shahjahan’s time.[10] Traces of blue and green tiles are still extant on the domes.

- The tomb complex was built in several phases, and this is evident from the differences in architectural styles. Can you identify them during your visit?

- Scholar Subhash Parihar, who has done some work on the adjoining madrasa, has a suggestion, ‘the personage commemorated in the main tomb was most probably Shaykh Sultan or Haji Sultan, the translator of the Hindu epics, the Mahabharata and the Ramayana.’

- A part of the tomb complex is constructed with ‘buff stone’, which was a common alternative for the expensive red sandstone and white marble.

- The Grand Trunk Road, which passed by this tomb, was an ancient trade and travel route for around 2,500 years, linking the Indian subcontinent with Central Asia. It was around 2,400 km-long and was also known as Uttarapath, Sadak-e-Azam, Badshahi Sadak. The East India Company gave it the name ‘Grand Trunk Road’. Rudyard Kipling’s Kim describes it.

This article was also published on The Indian Express.

Notes

[1] Sanjay Subodh, ‘Medieval Remains In Thanesar-An Exploration In Medieval Archaeology,’ Proceedings of the Indian History Congress 59 (1998): 989–1002. Accessed April 2, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/44147073.

[2] David Ross, The Land of the Five Rivers and Sindh (rept. ed., Patiala, 1970) via Subhash Parihar, ‘A Little-Known Mughal College in India: The Madrasa of Shaykh Chillie at Thanesar,’ Muqarnas 9 (1992): 175–85. Accessed April 8, 2020. doi:10.2307/1523142.

[3] Subhash Parihar, ‘A Little-Known Mughal College in India: The Madrasa of Shaykh Chillie at Thanesar,’ Muqarnas 9 (1992): 175–85. Accessed April 8, 2020. doi:10.2307/1523142.

[4]Catherine B. Asher, ‘Architecture of Mughal India,’ Cambridge Histories Online (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), https://archive.org/stream/iB_in/1-4_djvu.txt.

[5] Archaeological Survey of India: Four Reports Made during the Years 1962-63-64-65 (hereafter ASI Reports) (rept. ed., Varanasi, 1972); David Ross, The Land of the Five Rivers and Sindh (rept. ed., Patiala, 1970)

[6]Subhash Parihar, ‘A Little-Known Mughal College in India: The Madrasa of Shaykh Chillie at Thanesar,’ Muqarnas 9 (1992): 175–85. Accessed April 8, 2020. doi:10.2307/1523142.

[7] B.M. Pande and C. Dorje, Thanesar and Its Vicinity (New Delhi: ASI, 2016), https://archive.org/stream/thanesar00bmpa/thanesar00bmpa_djvu.txt.

[8] SubhashParihar, ‘A Little-Known Mughal College in India: The Madrasa of Shaykh Chillie at Thanesar,’ Muqarnas 9 (1992): 175–85. Accessed April 8, 2020. doi:10.2307/1523142.

[9] B.M. Pandeand C. Dorje, Thanesar and Its Vicinity (New Delhi: ASI, 2016), https://archive.org/stream/thanesar00bmpa/thanesar00bmpa_djvu.txt.

[10] Gordon Johnson (ed.), The New Cambridge History of India: Architecture of Mughal India (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), https://archive.org/stream/iB_in/1-4_djvu.txt.