Kerala has a long history of mural art and the mural paintings in churches, which probably developed along with the mural tradition of the temples here. Mural paintings are frequently found on the walls of the altar and its vaulted roof and occasionally on the wall of the nave. A few churches have paintings both in the altar and the nave.

The mural art tradition of the churches seems to have become prevalent after the arrival of the Portuguese in the fifteenth century and the classical period of mural art in Kerala is from the fifteenth-eighteenth century. Literary references suggest that the seventh session of the Synod of Diamper held in 1599 recommended that the churches set up some images in the main altar and the side altars under the direction of the priest. There were a total of one hundred and ninety-seven decrees in the Synod, organised into nine sessions on various aspects of Christianity like the matters of faith, sacraments, Eucharist, reformation of ecclesiastical disciplines, customs and morals. It is stated therein that,

Furthermore, That the images of our Lord Christ, and of our Lady the Glorious Virgin Mary and of the Holy Angels that are painted after our manner, and of other Saints which the Church believes to be in Heaven, ought to be kept and used in all decent places not only in the houses of the Faithful, but chiefly in Churches and Altars. (Geddes 1694: 129)

Mural paintings appeared in churches only after this Synod. Probably, the first of them appeared under the jurisdiction of the Portuguese Padroado and continued in the churches of Roman propaganda and other denominations. The beautification of the altar also, possibly, emerged in this backdrop.

A great number of the murals have been repainted. There are several churches with Portuguese murals in Cochin which portray the Virgin Mary, the saints, and biblical scenes with simplicity and different emotions. Their technique seems to have been indigenous and their design suggests Indian artists working under European instruction.

Early attempts to study the mural art of the churches of Kerala include a volume on Cochin murals edited by Chritra and Srinivasan (1940) and the works of PadmanabhanThampi (1952) and Devassy (1978). More recent works include those of Sashibhooshan (1998), Varghese (2009), and Peter and Gopi (2009). Varghese in his PhD thesis identified seventy-nine themes from five hundred paintings in the fifty Churches across Kerala. He also has classified them into eleven styles. The monograph on Church Mural art of Kerala by Jenee Peter and P.K. Gopi (2009) provides a glimpse of the churches in Kerala with mural paintings and the details of the mural panels.

Even though there are several churches with murals in Kerala, four churches have been selected here because permission was given by the authorities of these churches to enter the altar and document them. Also, these churches date back to the Portuguese period or before. The documentation of murals discussed below was carried out in the field seasons of 2015 and 2016. The sketches of ground plan of the altars prepared in Auto CAD and high resolution photographs are also provided. Plaster samples from St. Thomas (old) Church, Pala, were taken for X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) analysis and the composition was analysed at the Deccan College Post Graduate and Research Institute, Pune. The results are discussed here.

Mar Sabor and Afroth Jacobite Church

The Church is located (N10009’38.6; E076022’59.7) in Aluva taluk of Ernakulam district. The parish authority claims its antiquity from ninth century CE. Mar Sabor and Mar Afroth were two bishops, who came with a group of Syrian Christian immigrants from Persia. It seems they were given land to build the Church after their successful debate with the local religious heads. The church is believed to have been built in 825 CE and is named after these two patron saints. It is popularly known as the 'Church of the Qadishangal' (Qadishe means the Holy Ones in Syriac). The present Church has undergone modifications, probably on several occasions.

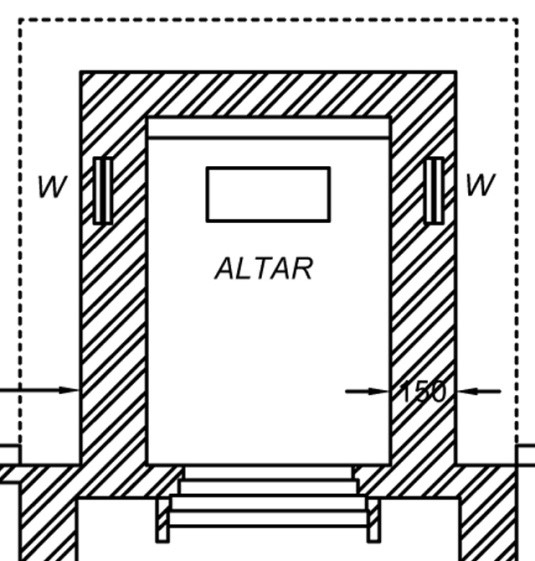

At present, the Church consists of a diminutive altar, a broad nave and a front porch. In the recent renovations, the old wooden side porches were removed and veranda was added on either sides of the nave. In plan, the rectangular altar measures 8 m x 5.6 m. The base of the wooden altar table measures 2.8 m x 1.2 m and it is detached from the east wall of the sanctuary. The thickness of the altar wall is 1.5 m and two windows on either side of the sanctum provide adequate light into the altar (see fig.1).

The paintings appear on the southern, northern and eastern walls of the altar. The colours used for the painting are blue, white, yellow, light and dark green, red, brown and ochre. There are 9 panels of painting on the southern wall of the altar. Out of the nine panels, eight are painted in two rows, one above the other. Each row consists of four panels and each panel has vertical and horizontal borders. The thick vertical borders are decorated with flowers and leaves whereas the thin horizontal border is filled with white colour.

The upper row of the southern panels (from the right) depicts (1) Jesus praying at Gethsemane garden while his three disciples sleep, (2) Jesus being arrested by nine soldiers in the presence of his four disciples, (3) Jesus being beaten up by three soldiers, and (4) soldiers fixing the crown of thorns on his head (see fig.2).

The mural in the lower panel is partially obscured by recent plastering and only a small part of it has survived. The lower panel (from the right on facing the panel) depicts (1) Jesus carrying the cross, surrounded by soldiers, (2) Jesus being crucified, (3) the third panel is completely destroyed, and (4) the fourth depicts the Resurrection of Jesus. A larger image of the Resurrection is depicted on the southern wall (see fig.3). The space above the panels is painted with horizontal lines of various colours, patterns and thicknesses. There is a row of angels at the centre and ten horizontal lines of different patterns and colours each above and below the angles.

There are eight panels in two rows on the northern wall of the altar. Each row consists of four panels. Each panel is separated by vertical and horizontal borders, as in the case of the southern wall. The upper row (from the left) depicts (1) Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, (2) God giving theTen Commandments to Moses, (3) Elijah and Elisa, and (4) King David sitting inside a chariot. The lower rows of paintings are partially lost mainly because of recent plastering. Two of the panels are visible and (from the left facing the panels) they portray (1) the disciples of Jesus receiving the Holy Ghost and (2) the visit of St. Thomas (see fig.4)

The arch shaped eastern wall of the altar has murals in its central and the upper portion. There are no paintings on the lower part. The murals on the eastern wall portray the altarpieces. Altarpieces are paintings or wooden works placed behind the altar. There are two rows of rectangular panels, one above the other and each consists of three panels of paintings. Facing the paintings, the depictions are, from the left, (1) either Mar Sabor or Afroth debating with the king and three brahmins, (2) Mar Sabor and Afroth, and (3) a bishop along with two priests and an assistant praying in front of a tomb. From the left, the upper panels portray (1) two soldiers beating a boy in the presence of a king, (2) the dead body of a boy being lowered into the cemetery by five people, and (3) a bishop. Paintings of coupled engaged spiral pillars (Solomonic) separate these panels vertically. The term Solomonic means a column with spiral shaft, crowned with Corinthian capital. Panels are horizontally separated by paintings of angels and flower motifs on the frieze. The whole painting is crowned by an arched element with a circular panel which shows the Resurrection of Jesus Christ. (see fig.5).

St. Mary’s Orthodox Syrian Church, Kottayam

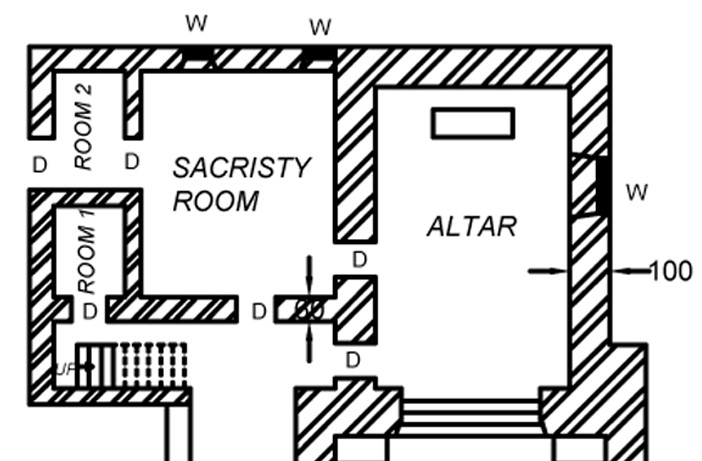

St. Mary’s Orthodox Syrian Church is located (N09035’44.9; E076030’40.1) in the Kottayam taluk of Kottayam district. It was built in 1579 CE. The longitudinal plan of the Church consists of a diminutive altar, broad nave and a front porch. It also has a porch on the southern side, covered veranda with upper storey on the northern side, sacristy room, and an outer wall with two gateways. The altar of the Church measures 7.6m x 4.9 m and has a thick outer wall of 1 m. The altar is accessed from the nave by three wide steps at the entrance arch. The northern wall of the altar has two doors and one of them provides access from the sacristy room. The second door leads to the veranda and a window on the southern wall admits light into the altar. The base of the altar table measures 2 m x 7 m and is detached from the eastern wall of the altar (see fig.6).

Mural paintings appear on the eastern, southern and northern walls and the vaulted roof of the sanctuary. The vaulted roof of the church is also painted with floral designs and cherub images. The colours used for the paintings on the northern and southern walls are brown, dark and light green, red ochre and black. Paintings on the vaulted roof and on the eastern wall seem to have been repainted recently. The eastern wall paintings are in the shape of altarpieces. The colours used in the paintings on the eastern wall are bright blue, black, red ochre, green, yellow, white and orange.

The northern wall of the altar has a long panel of paintings of a sequence of events. The events depicted (from right to left on facing the panel) are (1) the Last Supper; (2) a winged angel giving the chalice to Jesus as his disciples sleep at Gethsemane; (3) Roman soldiers along with a large crowd approaching Gethsemane; (4) Judas, holding his thirty silver coins, kissing Jesus; and (5) Jesus being produced in front of Pilate (see fig.7).

The southern wall of the altar (from right to left) portrays (1) Jesus surrounded by the Roman soldiers, (2) Pontius Pilate washing his hands with water, (3) Jesus carrying the cross, (4) the Crucifixion scene which shows Mother Mary and two other women, and (5) Mary holding Jesus on her lap (see fig.8).

The eastern wall of the altar has three levels of paintings, one above the other. The lower row portrays (facing the panels, from left to right) St. Peter, Angel Gabriel with Mary, Mother Mary and Elizabeth, amd Mary and Joseph with child Jesus and St. Paul. The middle row shows two angels venerating Mother Mary and child Jesus. The upper row has the images of angels and the coronation of Mother Mary in heaven (see fig.9).

St. Mary’s Church, Kanjirappally

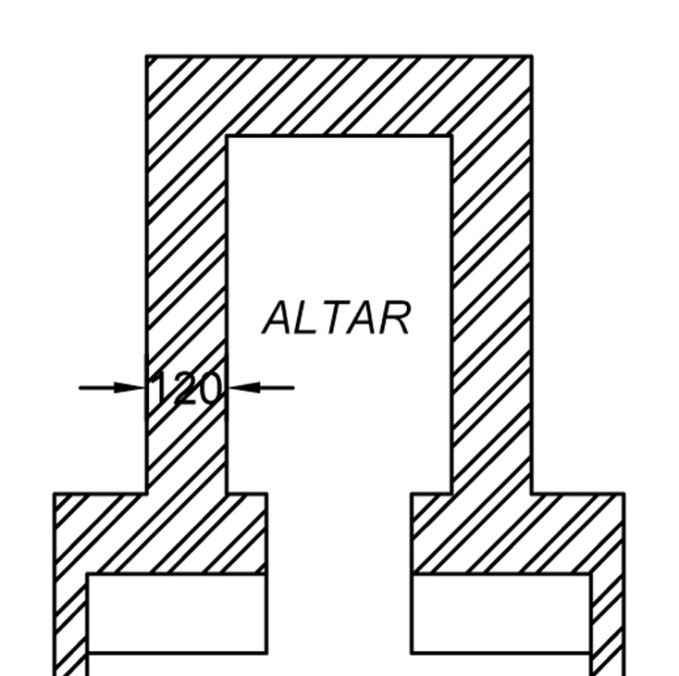

St. Mary’s (old) Church is located (N09033’31.9; E076047’33.3) in the Kanjirappally taluk of Kottayam district. It is believed to have been built and consecrated on 8 September 1449. The Christians of the region had patronage from the local king to build the church. The first church building was made using available local raw materials like wood and stone. The church received patronage from Veera Kerala Perumal of Thekkumkur in 1522 CE. The church is quite small in dimensions and consists of a diminutive altar (see fig.10) and nave. The altar measures 5.3 m x 3.4 m. It has an altar table on the eastern wall and tabernacle. Miniature windows on each side provide light to the altar. The sanctuary is separated from the nave by a narrow entrance arch and is flanked by side altars facing the nave. The altar does not have any retable in it. However, the eastern wall has murals that portray the retable. The retable is a large elaborate screen erected as a wall behind the altar table. It is a structural element with decorations, placed above and behind the altar table and is found as either attached to the eastern wall or detached from it.

The vaulted roof of the Church is also decorated with cherub images and symbols. The entire painting was retouched recently.

The colours used in the painting are light brown, black, light green, light blue and white. The paintings on the eastern wall are portrayed inside the altarpieces (see fig.11).

The lowermost row, from left to right facing the panels shows (1) the Baptism of Jesus by St. John, (2) Mother Mary, (3) Mother Mary, Mary Magdalene and St. John, and (4) St. George. The middle row portrays (1) Angel Gabriel with Mary, (2) two thieves on crosses, and (3) Nativity of Jesus with Mary and Joseph. The upper row has the image of Jesus and the altarpieces are flanked by St. Peter and St. John. The pilasters and the frieze of the altarpieces are painted with winged angels, twining leaves and grapes and geometric patterns.

St. Thomas Cathedral Church, Pala

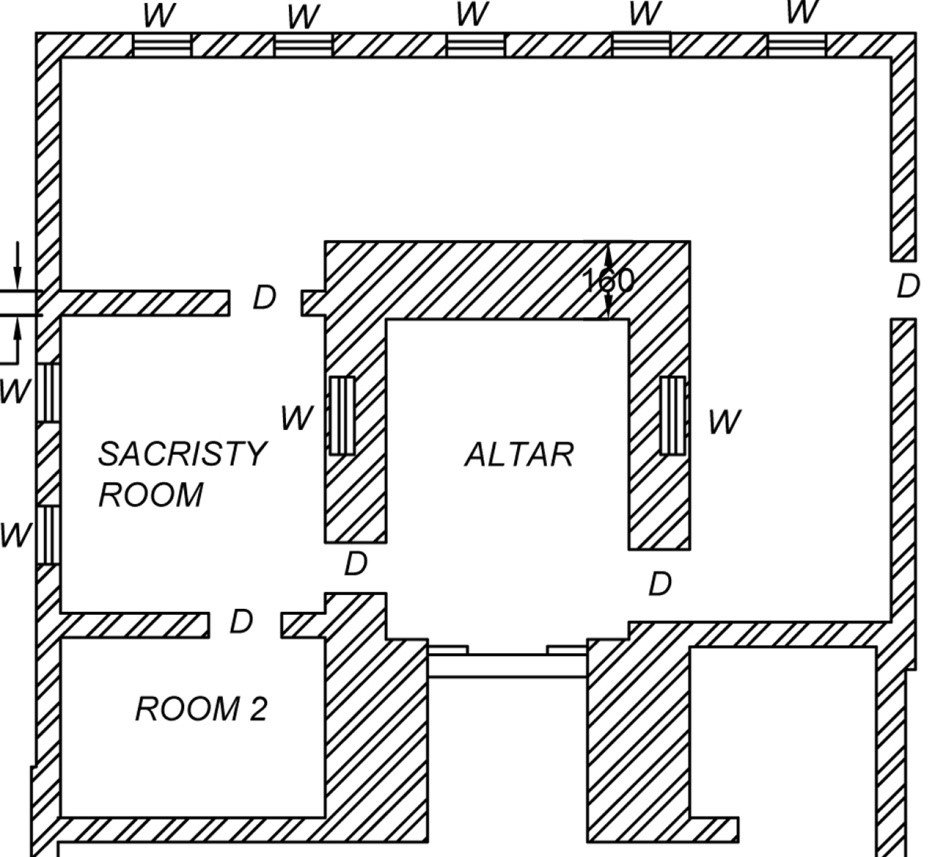

St. Thomas Cathedral (old) Church is located (N09042’19.2; E076040’49.6) in the Meenachil taluk of Kottayam district. The foundation for the first Church is believed to have been laid on 3 July 1002. But, with the advent of the Portuguese and their influence, the church was rebuilt and renovated in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries CE. The longitudinal plan of the Church consists of an altar and a nave (see fig.12).

It also has a covered veranda on both sides of the nave, a sacristy room and several other rooms around the altar. The altar of the St. Thomas Cathedral has a luxuriously ornamented wooden retable. The altar wall is 1.6 m thick and has a single window and door on two side. The sacristy room is on the northern side of the altar. However, several connected rooms were constructed around the altar. The floor level of the altar has been reduced to the present level in order to create access to the side rooms. The railing of the Kestroma (Kestroma is the transitional space between the nave and the altar.) is kept inside the sanctuary arch at present.

The murals of this Church were painted on the eastern wall of the altar behind the retable. The retable is erected against the eastern wall of the altar and it partially concealed the murals. Today, the paintings can be seen through the narrow doors provided on either end of the retable. However, considerable areas of the murals are covered by it. Four images are visible properly: the image of Jesus, Resurrection of Jesus, image of Peter and Paul. The colours used for painting are red ochre, brown, white, black, green, red and yellow (see fig.9).

X- ray diffraction (XRD) Analysis

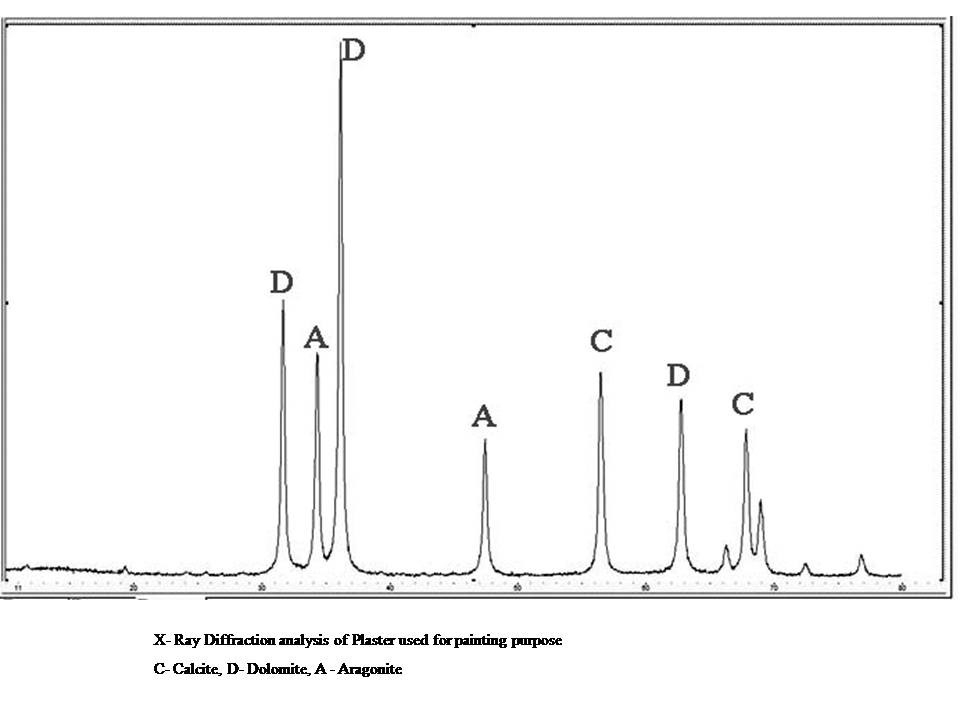

X ray diffraction method is used to characterise solid state materials. It gives qualitative and quantitative information about the nature of materials present in a sample. In this technique, the position and intensity of the diffraction peaks give the crystal structure and hence will help to identify the unknown components present in a solid state sample. It can be employed as an effective tool in the studies of murals. I have collected lime plaster sample of five grams from St. Thomas (old) Church, Pala for X ray diffraction analysis.

The XRD analysis of the sample shows three different minerals in the graph. The plaster is a mixture of Calcite, Dolomite and Aragonite minerals. Siliceous material like quartz is completely absent in the XRD pattern (see fig.13) Calcium oxide is found in the form of Dolomite. Aragonite which is used in the plaster can be collected from the sea shore because Aragonite mineral is a form of calcium carbonate which is found only in shells. Dolomite and calcite have been located around the site. Smooth wall surface cannot be obtained if silica is present in the mixture of plaster. Absence of silica clearly indicates that plaster was used for preparing the base of the painting.

Discussion and Conclusions

The practice of painting murals in churches emerged after the Synod of Diamper in 1599. To understand their evolution, murals are also to be reviewed in terms of the architecture of the churches. The churches studied are orientated from east to west with the altar on the east. Murals usually appear on the southern, northern, and eastern walls as well as on the vaulted roof of the altar. The altar has a narrow opening from the nave and also has a thronose (retable). The retable and decorative elements of the altar of each church look different but share some commonalities. The European influenced wooden retable, with elaborate decorations, are mostly found in the altars of the Syrian and Latin Catholic Churches whereas a simple wooden thronose decorated with flower motifs and geometrical patterns is found in the altars of the Jacobite and Orthodox Churches. The murals of the St. Thomas Church, Pala, appear on the eastern wall and are not fully visible because of the retable, as discussed earlier, but they can be viewed to some extent through the narrow doors provided at each end of the retable. The retable is erected against the eastern wall of the altar and is a little detached from it without hiding the murals. The Jacobite Church, Akapparambu, also has a wooden thronose which is detached from the eastern wall. St. Mary’s Orthodox Church, Kottayam, does not have an elaborate wooden thronose. Instead, it has an altar table for the Holy Eucharist and the eastern wall of the altar is painted. Some of the panels are retouched. A similar pattern of the altar is found at St. Mary’s Church, Kanjirappally, where the painted eastern wall is highlighted above the altar table without any retable. Similar patterns of arrangement of retables and paintings have been found at several churches in central Kerala. The nature of the paintings and the retable shows that placing murals on the eastern wall of the altar was a practice that existed before the introduction of the decorated retable on the altar. The intricately decorated retable is a later addition to the churches. Hence, the tradition of mural paintings in churches probably pre-dates the introduction of the retable into the altar of the churches.

The customs related to churches, like festivals, rituals, offerings, songs, dance forms, etc., predominantly reflect regional cultural behaviour. The mural paintings in the churches also were influenced by it. Even though the paintings in churches are different from those in palaces and the temples, they share some common features. The techniques used for painting and plastering as well as colours are very similar. Their subject matter, in churches, includes events from the Old Testament, events from the New Testament, illustration of saints and angels, depiction of social and religious events of the region, flower motifs and miscellaneous motifs. Colours used for the paintings are white, black, brown, different shades of yellow, red and ochre, different shades of green and blue.

The idea of decorating the altar with paintings developed after the Synod of Diamper and it has been influenced by the regional painting traditions. The tradition of painting murals continued even after new architectural components were introduced in the churches. The surviving murals in the study area have been re-painted at different times but no records are available in the churches about these renovations. Moreover, some of the early paintings have even lost their distinctiveness due to re-paintings.

Bibliography

Amaladas, A. and G. Lowner. 2012. Christian Themes in Indian Art from Mughal Times till Today.New Delhi: Manohar Publications.

Chitra, V. R and T.N. Srinivasan.1940. Cochin Murals: Collotype reproductions of the Mural Paintings of Cochin based on Photography. Cochin: Special Authority of His Highness of Maharaja of Cochin.

Devasy, M.K.1978. Keraleeya Christhava Devalayangalile Shilpa Chitra Kalakal (Sculptural and Mural art of Churches in Kerala). Puthenchira:

Ferroli, D. 1939. Jesuit Missionaries of Malabar. Bangalore: Bangalore Press.

Geddes, M.1694. The History of Church of Malabar, from the time of its being first discovered by the Portuguese in the year 1501., London: Prince’s arms Arms in St. Paul’s Church yard.

Gouvea, A.1606. Jornado do arcebispo de Goa Dom Friei Aleixo de Menezes, (Translated in English by Pius, Malekkandathil.2003). Jornada of Dom Alexis de Menezes: a Portuguese Account of the Sixteenth Century Malabar: Cochin: LRC Publications.

Jose, C., R.K. Mohanty, 2017. ‘Antiquity of Christianity in India with Special reference to South Central Kerala’, in Heritage: Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology, V:, 100-139.

Jose, C.2017. Cultural Landscape and Architecture of Medieval Churches of Kerala. Ph.D. Thesis, Pune: Deccan College Post Graduate and Research Institute.

Kramrisch,S., J.H. Cousins and R.V.Poduva eds.1948 (Reprint 1999).The Arts and Crafts of Travancore,.TrivandrumTravancore. Trivandrum: Department of Cultural Publications, Government of Kerala.

Meenachery, G.1973. The St. Thomas Christian Encyclopedia of India, Volume-II:Madras: B.N.K Press.

Menachery, G. 2005. Pazhama 2, Handbooks to the Study of the Heritage, Culture, and Early History of St. Thomas Christians. Thrissur: The South Asian Research Assistance Service.

Pereira, J.2000. Baroque India, the Neo Roman Architecture of South Asia: A Global Stylistic Survey. New Delhi: Aryan Books International.

Peter, J. and P.K Gopi.2009. A Monograph on Church Mural Art of Kerala,Thripunithura: Centre for Heritage Studies.

Prabhubalagopal, T.S.1999. ‘Kerala Architecture’, inEssays on the Cultural Formations of Kerala, Volume IV, Part II, ed. P. J. Cherian, pp 271-300, Trivandrum: Government of Kerala.

Rangacharya, V. 1940. ‘The Cochin Murals, Historical Background’, in Cochin Murals: Collotype reproductions of the Mural Paintings of Cochin based on Photography,Ededs. Chitra,V.RV.R. Chitra and T.N.Srinivasan, pp 81-102,Cochin: Special authority Authority of His Highness of Maharaja of Cochin

Sasibhoshan, M.G.2000.KeralathileChuvarchithrangal (Mural paintings of Kerala)., Trivandrum: State Institute of Languages.

Skoog, D.A., Holler,F.J., and Crouch,S.A. 2007. Principles of Instrumental analysis, 6th Edition: Belmont, Thomson Books.

Sreeniwas, S. 2008. ‘Portuguese Impact on Architecture, Printing and War Technology in Cochin’, Journal of the Vasco de Gama Research institute of Cochin 3:, 55-57.

Thampi, P. 1952. Report in the bulletin Bulletin of Cochin State Department of Archaeology, 1951-1952. Cochin: Cochin State Department of Archaeology.

Varghese, G. 2009. Keralathile christava Christava DevalayangalileChumarChithrangalumAltharaChithrangalum, Oruvimarsana Padanam (A critical Critical Study on the Church Mural Paintings of Kerala). PhD. Dissertation, Kottayam: School of Letters, M.G University.

Ward and Conner.1863. Reprint 1994). Memoir of the Survey of the Travancore and Cochin States, Volume 1: Trivandrum: Gazetteers Department Government of Kerala.

Zacharia, S. 1994.The Acts of the Synod of Diamper -1599. Edamattom: Indian Institute of Christian Studies.