Shahids (martyrs)[1] play a significant role in the history of the Sikh Panth (Sikhism) and its popular visual culture.[2] The shahadat tasveeran (martyrdom images),[3] which is a recurring motif in the delineation of the glorious history of the Sikh qaum (quam is a Persian word used both for religion, community and nation), start from the visual narratives of the horrific torture, self-sacrifice[4], and the death of the Sikh gurus (Arjan Dev, the fifth guru, on May 30, 1606, and Teg Bahadur, the ninth guru, on November 24, 1675), companions of gurus (Bhai Dayala on November 11, 1675, Bhai Mati Das and Bhai Sati Das on November 24, 1675) and Sikh warriors (such as Banda Singh Bahadur on June 9, 1716, and Baba Deep Singh on November 11, 1757) during the tyrannical Islamic rule of the Mughals and barbaric Afghan invasions in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Later, the military history of Sikhism enriched the tradition of martyrology,[5] including episodes of Sikh freedom fighters during the British rule in the early twentieth century; Sikh victims in the communal riots during Partition in 1947; agitators of Punjabi Suba Movement after Independence (in the 1960s) who died in police firing; uggravadi[6] (militants) of the Khalistan movement in the 1980s and 1990s; Sikhs who died in military operations such as Operation Black Thunder and Operation Woodrose; the partial carnage of the Akal Takht (one of the five seats of power of the Sikhs) at Shri Harmandir Sahib—popularly known as the Golden Temple—at Amritsar in the army action Operation Blue Star (on June 3–8, 1984), known as Ghallughara Dihara[7] (day of the genocide or genocide at the golden temple) and Fauji Hamla (army attack)—which mark the carnage of the Akal Takht of Shri Harmandir Shahib at Amritsar on June 6, 1984—and the anti-Sikh communal riots (on November 1–4, 1984)[8], allegedly perpetuated by Congress leaders[9] after the assassination of then prime minister Indira Gandhi on October 31, 1984, by her Sikh bodyguards Beant Singh and Satwant Singh.

The images from different time periods create a compelling visual narrative of suffering, death and martyrdom. These images become the prototypes and the ideal of the actualisation of the historical visual narratives of tortured bodies[10] as well as testimony. These are also used as a pedagogic tools to propagate religion, moral obligation and gender roles to Sikh youths. They encourage them to be ready for the shahadat to protect their quam and gurdwaras like their predecessors. The suffering translates to courage and pride for the Sikh community.

These images of suffering[11] can be viewed at Sikh ajaibghars (museums—both missionary and public), gurdwaras and langar halls (Sikh community dining halls) and on banners, posters, popular prints, calendars, book illustrations, comics, T-shirt prints and even on Internet forums.

The visualisation of the textual and mnemonic history of courage, suffering, trauma, horror, and death of gurus, heroes, warriors, martyrs and victims starts in the late twentieth century (after the 1950s). It can be viewed as a pervasive tendency of universalisation of trauma[12] within the realm of popular culture, which creates a collective consciousness and consolidates the entire community.

These images serve five principal purposes: first, images recall past suffering and commemorate the shahids; second, they actualise history in a static visual format; third, they are used as a tool to propagate religion, morality and pedagogic strategies to educate Sikh youths; fourth, they give information to non-Sikhs about the Sikh religion; and, finally, they underscore the Sikh claim to be a unique community, culture and religion, and not a branch of Hinduism.[13] The power of the images[14] sanctions the consolidation and self-consciousness among the Sikh community.

Modern Sikh History and Martyrdom Painting

The first wave of modern Sikh visual culture starts with the emergence of the Kendriya Sikh Ajaibghar (KSA) or Central Sikh Museum (CSM) at Shri Harmandir Sahib, established in 1958 by the Shiromani Gurdwara Prabandhak Committee (SGPC). The primary intention was to restore and exhibit relics of the Sikh gurus, such as their handwritten texts, weapons, garments and other used articles.

The SGPC started employing Sikh artists to visualise Sikh history in 1956. Artists such as Sobha Singh, Kirpal Singh, Gyan Singh Nakkash, S.G. Thakur Singh, G.S. Bansal, G.S. Sohan Singh and Satpal Singh Danish were tasked with portraying the narrative of Sikh history on oil canvases, emphasising the lives and the shahadat of Sikh gurus, heroes and warriors. The visual stories are exhibited on narrative canvases in the chronological order of Sikh history, starting from Guru Nanak to the last Sikh guru, Guru Gobind Singh, with important events, war history and martyrdoms. All of the oil canvases follow the European or Western representational art style.

The SGPC project established a visual language and vocabulary of shahadat tasveeran, which later became prototypes and ideals for other Sikh history painters and the anonymous bazaar artists. Gradually, these images entered into the realm of popular and calendar art, posters, banners, T-shirt prints, book illustrations, comics, etc. The transmediality (transition of an image from one medium to another) is an essential phenomenon of Sikh visual culture.

Later, other gurdwaras that are controlled by the SGPC and Delhi Sikh Gurdwara Management Committee (DSGMC) opened missionary museums at other important places. Bhai Mati Das Museum (BMDM) in Chandni Chowk, Delhi, Baba Baghel Singh Sikh Heritage Multimedia Museum (BBSSHMM) in New Delhi, Sri Guru Teg Bahadur Sikh Museum (SGTBSM) and Historical Picture Gallery (HPG) in Anandpur Sahib, and public museums such as Virasat-E-Khalsa (VEK) or Khalsa Heritage Centre (KHC) in Anandpur Sahib and the War Museum (WM) in Amritsar are other Sikh missionary museums.

Two Sikh history painters, Sobha Singh and Kirpal Singh, created two schools of history painting within the Sikh visual culture—those with peace and tranquility as their theme and those with martyrdom, respectively. Central Sikh Museum paintings become the ideal for new-generation Sikh history painters, like Gurvinderpal Singh, now senior painter at the museum, who counts both the painters as his influences.

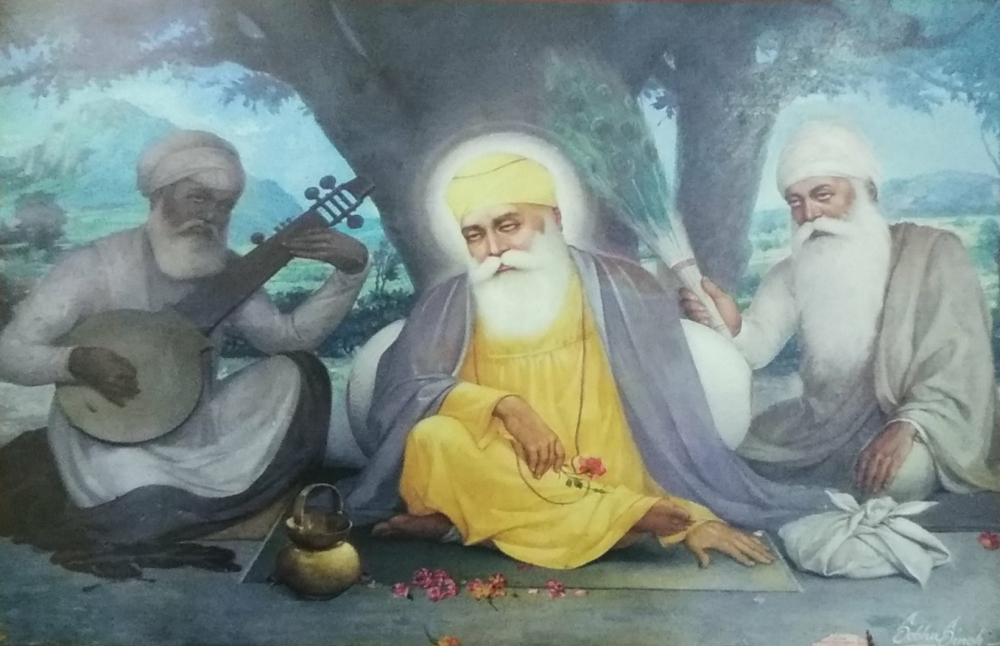

Sobha Singh was the first modern Sikh painter who visualised the inner spirituality, and the mental and physical stability of the religious figure of Guru Nanak Dev and the other nine Sikh gurus and heroes. The faces of the figures reflect calmness and serenity. The principal rasa[15] or sentiment of his paintings is shanta rasa (peace). Sobha Singh followed the textual descriptions and folk stories on gurus to imagine the holy characters. He also used the symbolic representation of the characters which were defined by the earlier Pahari painters in the Guru Portraiture or Janamsakhi manuscript illustrations (an old manuscript on the biography of Nanak, illustrated by the painters of the Pahari schools for their Punjabi patrons). One of his portraitures of Guru Nanak Dev (Fig. 1) now exhibited at the Central Sikh Museum is among the more-circulated guru images in popular print and calendar art and on the Internet. It shows Guru Nanak Dev sitting in the shadow of a tree with his two companions, the Muslim musician Mardana and Jatt Bala. The central character in this painting is Guru Nanak Dev, who sits between Mardana (on the left) playing the rabab (a stringed instrument) and Bala, who is fanning Guru Nanak Dev with a peacock feather fan (on the right). A halo above Guru Nanak’s head conveys his divinity. Sobha Singh painted a moment from Guru Nanak’s days of udasi (travel), when he travelled to every holy pilgrimage of India and visited Mecca, the sacred pilgrimage centre for Muslims.

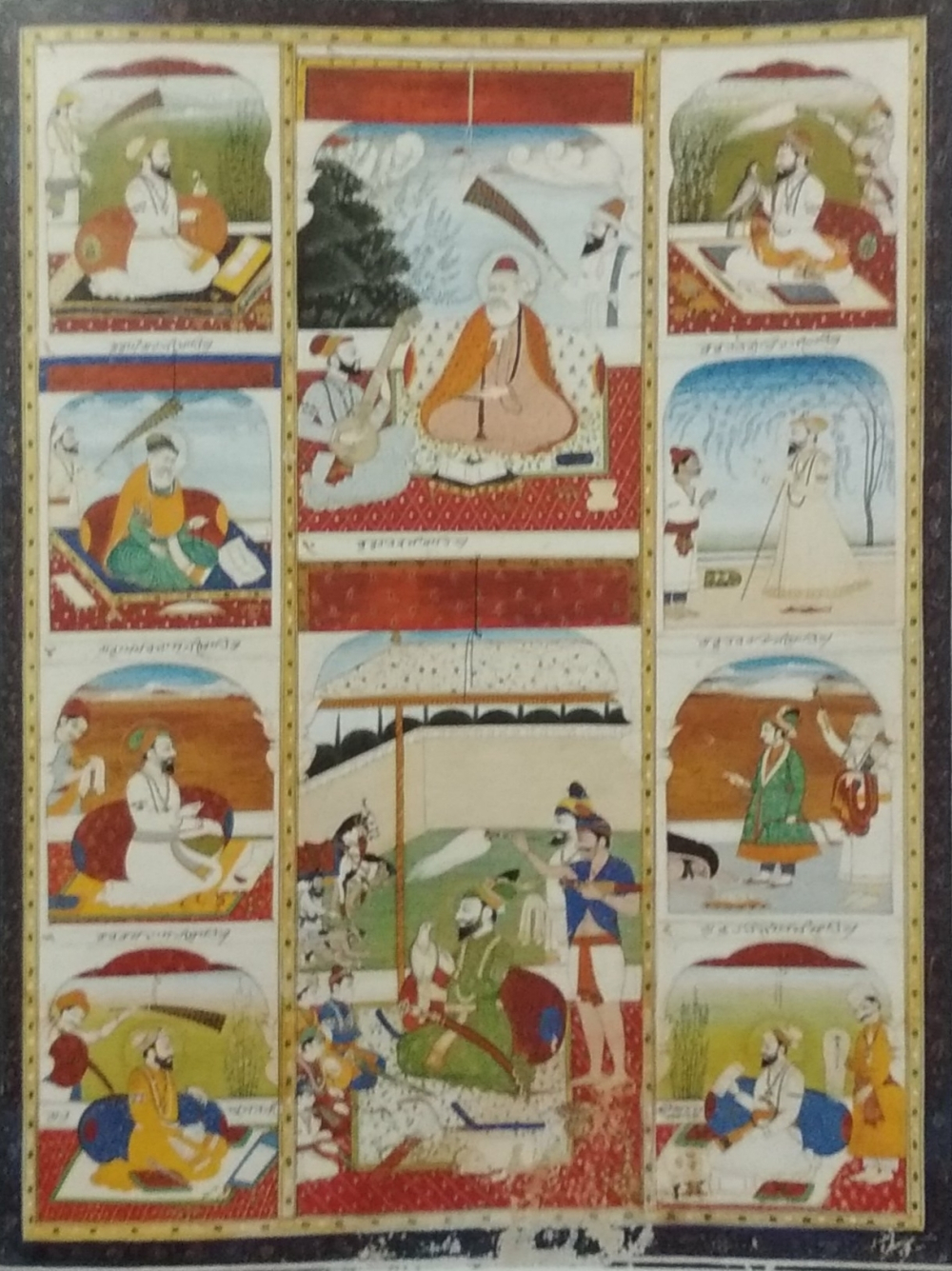

Sobha Singh uses elements and the symbolic visual language of the Pahari painters in the early nineteenth century. We also find some reference from a set of portraitures of the 10 Sikh gurus executed in the early nineteenth century from the Janamsakhis (Fig. 2), where Guru Nanak Dev is painted at the central upper panel. Sobha Singh borrows this visual language in his paintings.

His other two portraits (Fig. 3) of Guru Nanak Dev show spiritual greatness. The eyes of the portraits are half-closed and look downwards toward the heart. The palm of the right hand is held in abhaya mudra (the hand gesture of fearlessness). The glance and hand gestures of these two paintings echo the visual language of portraying a holy figure of Buddhist and Hindu art.

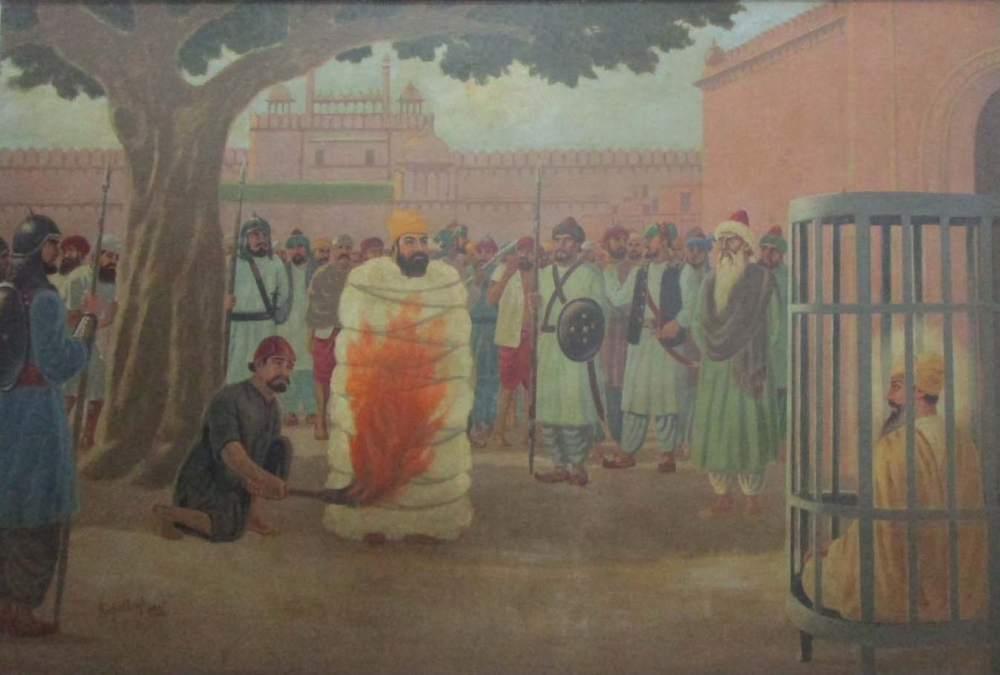

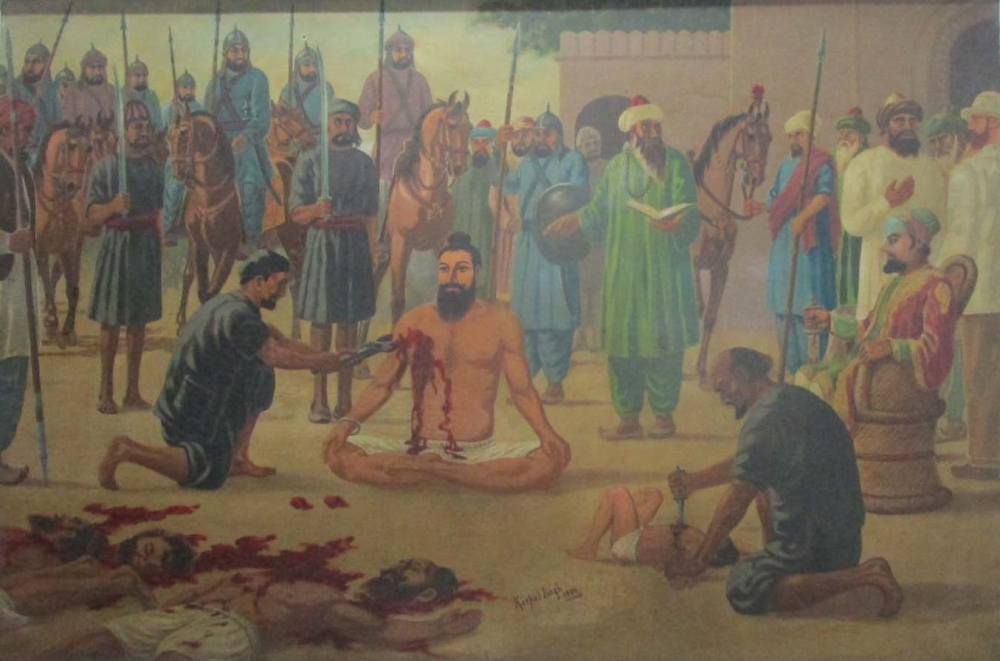

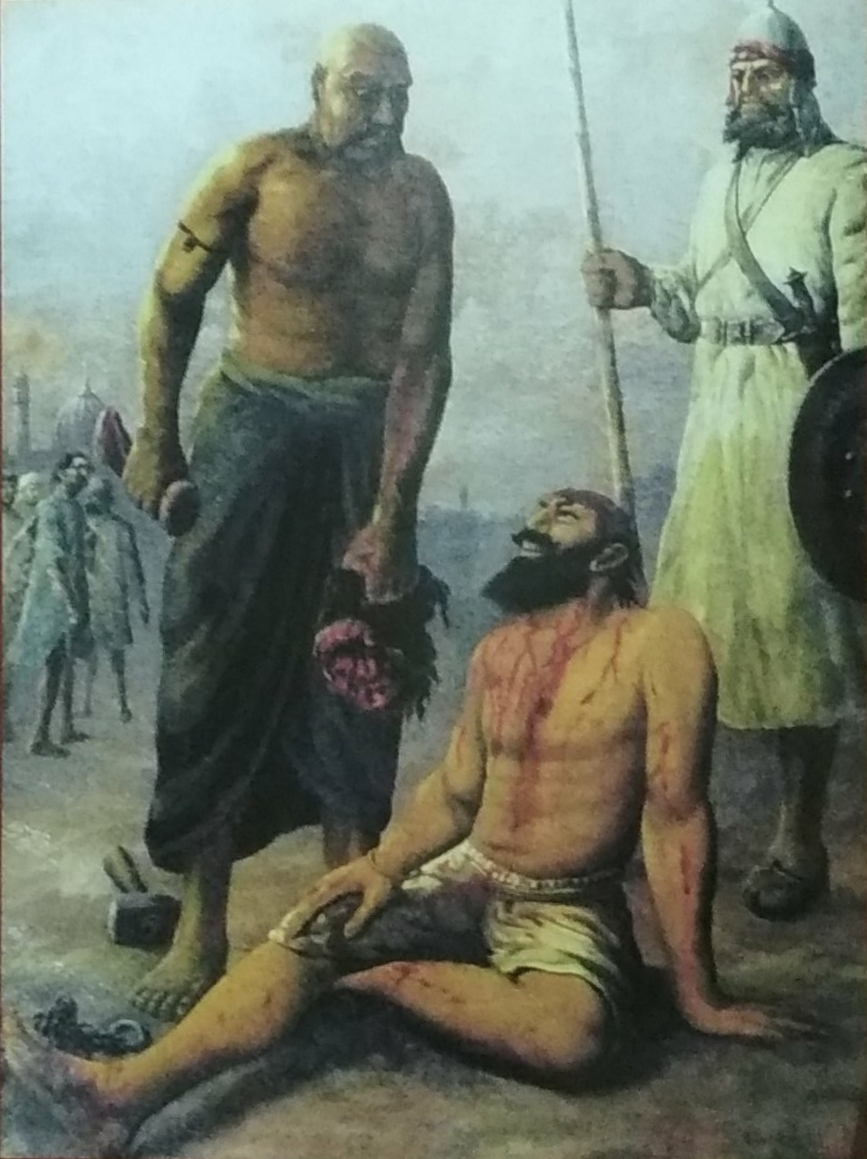

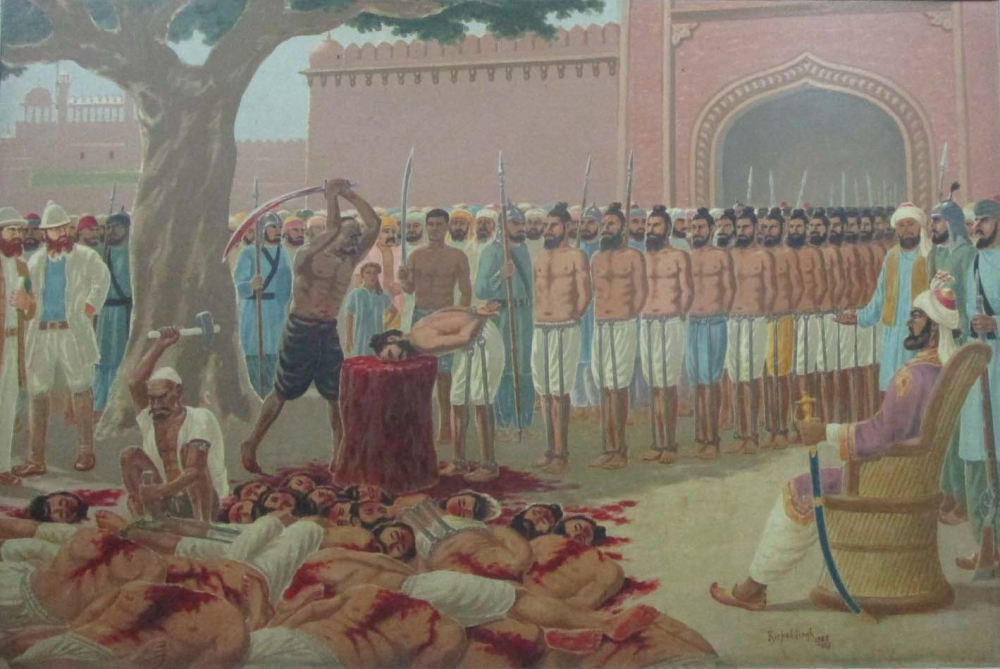

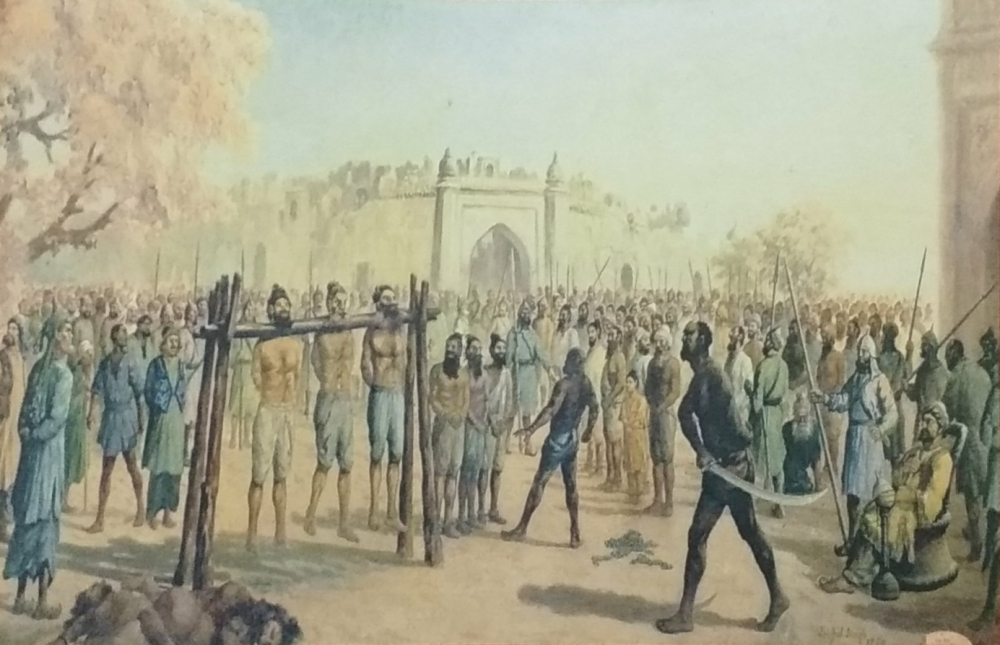

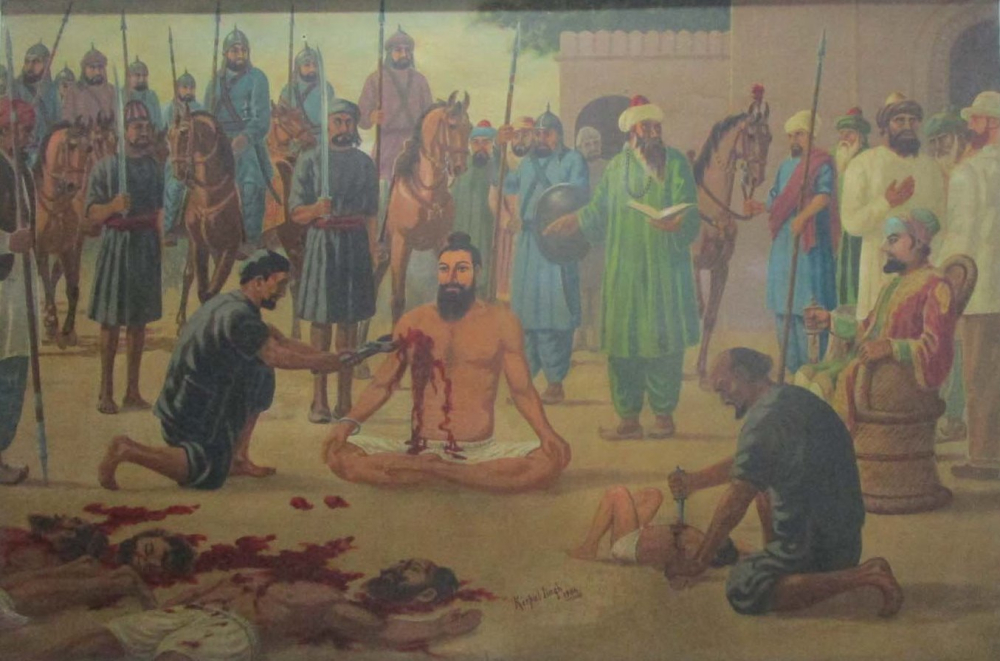

In contrast, Kirpal Singh mainly reconstructed the history of martyrdoms and the Sikh wars. His characters were either strong warriors or those facing horrific death. The principal rasa of his paintings is veer rasa (valour) along with bibhatsa rasa (disgust) and bhayanaka rasa (terror) as secondary rasas. He mainly chose the narratives of martyrdoms, genocide and death. He actualises the horrific death of Bhai Dayal (Fig. 4), Bhai Mati Das (Fig. 5), Bhai Sati Das (Fig. 6), Banda Singh Bahadur (Fig. 7), Deep Singh, Bhai Mani Singh, Bhai Taru Singh (Fig. 8), Bhai Subeg Singh (Fig. 9), Nikka (small) Ghallughara (Fig. 10) and Vadda (big) Ghallughara (Fig. 11).

To protect the religion of Kashmiri Brahmins, the ninth Sikh Guru, Teg Bahadur, and his three companions, Bhai Dayala, Bhai Mati Das and Bhai Sati Das were martyred. Dayala was boiled (on November 11, 1675), Mati Das was sawed (on November 24, 1676), and Sati Das was burnt alive (on November 24, 1675) at the kotwali (police station) of Chandni Chowk by order of Emperor Aurangzeb. They dedicated their lives to their beloved guru and qaum and faced suffering for not accepting Islam. Guru Teg Bahadur was also finally executed on November 24, 1675. All four were martyred for protecting their right to practise religion and reject forceful conversion. Their suffering for a noble cause made them great souls.

The two great Sikh warriors, Banda Singh Bahadur and Deep Singh, are portrayed as macho heroes (Fig. 12) with heavy armours and weapons. Figure 13 narrates the martyrdom of Banda Singh Bahadur on June 9, 1716, when his body was cut into pieces.

Kirpal Singh also narrates the execution of Bhai Mani Singh on December 1737 as well as Bhai Taru Singh and Bhai Subeg Singh’s martyrdom. Bhai Taru Singh’s scalp was torn off by order of Zakaria Khan, governor of Lahore, for not accepting Islam, and he died on July 1, 1745. Bhai Subeg Singh was tied to the death wheel and martyred in 1945 by order of Yahya Khan, son and successor of Zakaria Khan.

Most of these canvases narrate the suffering and death and visualise the moment of execution of these historical characters. They are painted like a testimony or visual documentation witnessed by the artist. The faces of the martyrs are calm and do not show any pain and suffering. It may have been the strategy of the artist to show the victory of Sikh bravery over cruelty and barbarism.

Figures 10 and 11 show the genocide of Sikhs by the Mughals and Afghans in the eighteenth century during the Nikka Ghallughara (‘small genocide’ by the Mughals in 1746) and Vadda Ghallughara (‘big genocide’ by the Afghans in 1762).

The 1984 canvases of the Delhi Sikh Gurdwara Management Committee project at Bhai Mati Das Museum narrated the martyrdoms of Bhai Dayal, Bhai Mati Das, Bhai Sati Das, Banda Singh Bahadur and scenes from the Nikka Ghallughara. The backgrounds of Kirpal Singh’s 1950’s canvases at the Central Sikh Museum are mostly blurred. The primary intention of the paintings is to tell the main story through the main historical characters in Sikh history, other anonymous subordinate characters and minimal arrangement of objects. The emphasis of the artist is on arranging the figures and illuminating the characters. Some of his paintings from 1950 were repainted in 1984 with a more sophisticated technique.

After the Khalistan movement and Bhindrawale

Khalistani militancy, Operation Blue Star, the Delhi anti-Sikh riots and police-military surveillance operations in Punjab created a new wave of the art of suffering. Artists start creating the portraiture of anonymous fearless kharkus (Khalistani heroes). The Shahadat Tasveeran Gallery at the Central Sikh Museum displays the portrait of Bhindranwale, leader of Khalistani militants, Indira Gandhi’s assassins Satwant Singh and Beant Singh, and other Khalistani militants and victims of the military operation at Shri Harmandir Sahib.

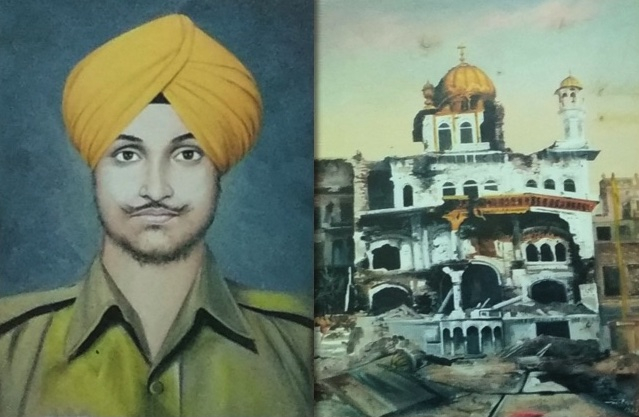

The portraits of Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, Beant Singh, General Shabeg Singh (a companion of Bhindranwale) (Fig. 14), Satwant Singh and the Akal Takht (Fig. 15) immortalise the wounds of 1984. One side of the Shahid Gallery is reserved for portraits and photographs of militants and victims of Ghallughara Dihara or Fauji Hamla at the Shri Harmandir Sahib. This gallery (Fig. 16) also displays portraits of shahids of the Sikh qaum during political agitations and conflict between other sects of Sikhism and Khalsa, from the 1960s to the 1990s. The dead become the holy souls, and their portraits are the documents of their suffered history.

Bhindranwale, painted by Gurvinderpal Singh, is represented in the painting (Fig. 14) as a bare-footed sant-sipay (hermit-warrior). He wears a white chola (ceremonial Sikh garment) and blue turban which are the Khalsa dress code for a sant-sipay. He holds an arrow in his right hand and a sword in the left hand; a kirpan (ceremonial dagger) and a bullet belt can also be seen on him. Bhindrawale is painted in a formal stance on heavenly clouds between the Akal Takht on the left and the Darbar Sahib on the right.

The other three portraits are photo-realistic copies from the photographs by the same artist. The painting of the destroyed Akal Takht, by Amolak Singh, symbolised the brutality of state machinery. The architecture becomes the martyr. The painting on the carnage of Akal Takht creates a sharp binary between sufferer and oppressor.

Shahadat tasveeran (martyrdom imageries) of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries commemorate the history of suffering in Sikhism. Shahids are not only heroes of the Sikh qaum but also an ideal, remembered in every congregational and individual Sikh prayer, ardas (prayer) at gurdwaras and Sikh homes. The second stanza of the ardas commemorates the martyrs from the seventeenth to eighteenth centuries and recalls other anonymous martyrs of contemporary times. It also advises Sikhs to be ready for martyrdom.

Visualisation of martyrdom is a modern phenomena. It started in the twentieth century and continues in the twenty-first. The paintings are seen as visual documents of the past for the Sikhs. They recall the past suffering and use one of the pedagogic tools to educate the youths about their past. They also inform to non-Sikhs about the history of Sikhism.

The martyrs create a notion of idealism—of bravery, morality and gender roles. Women in the martyrdom scene are cast in submissive roles. A brave woman is a daughter, mother or wife of a martyr. The role of the woman is to support the martyrdom of her son, father or husband. The suffering of the woman is in the loss of her children, father and husband, viewed akin to the suffering of orphans, bereaved mothers or widows. The active participation of women in the canvases is sporadic. The physicality of macho-male bodies of warriors defines the masculinity of the Sikh culture. Women are the silent supporters of the tradition of masculine martyrdom.

All of the martyrdom paintings create a sharp binary between Sikhs and their enemies, whether the Mughals, Afghans, British or the Indian state. The paintings at the Sikh museums become the prototypes and can be viewed in the realm of popular prints, entering households in the form of posters and calendars. There is usually at least one poster of gurus and martyrs in every Sikh house, gurdwara, langar hall or Sikh shop. The images are also reprinted on T-shirts, banners and billboards and circulated on Internet forums.

Notes

[1] Fenech, ‘Introduction,’ 1–15.

[2] McLeod, Popular Sikh Art.

[3] Chopra, ‘A Museum, a Memorial, and a Martyr,’ 97–144.

[4] Storm, Head and Heart.

[5] Fenech, ‘Martyrdom in the Early Sikh Tradition,’ 116–44.

[6] Chopra, ‘A Museum, A Memorial, and a Martyr,’ 97–144.

[7] Ibid., 103.

[8] Chopra, ‘Commemorating Hurt,’ 119–52; ‘A Museum, a Memorial, and a Martyr’, 97–144.

[9] Suri, 1984: The Anti-Sikh Violence and After.

[10] Axel, ‘The Tortured Body’, 121–57.

[11] Hadj-Moussa and Nijhawan, eds., Suffering, Art and Aesthetics, 1–19.

[12] Nijhawan and Schultz, ‘The Diasporic Rasa of Suffering,’ 178.

[13] Nabha, We Are Not Hindus.

[14] Freedberg, The Power of Imagese.

[15] Rasa, the aesthetic object, is a product of dramatic and other fine arts. It is not to be found in creations of nature. It is often used for aesthetic experience. See Pandey, Comparative Aesthetics, 21.

Bibliography

Axel, Brian Keith. ‘The Tortured Body.’ In The Nation's Tortured Body: Violence, Representation, and the Formation of a Sikh Diaspora, 121–57. Durham: Duke University Press, 2001.

Brar, K.S. Operation Blue Star: The True Story. New Delhi: USB Publishers' Distribution, 1993.

Chopra, Radhika. ‘A Museum, a Memory, and a Martyr: Politics of memory in the Sikh Golden Temple.’ Sikh Formations: Religion, Culture, Theory 9, no. 2 (2013): 97–114.

———. ‘Commemorating Hurt: Memorizing Operation Blue Star.’ Sikh Formations: Religion, Culture, Theory 6, no. 2 (2010): 119–52.

Fenech, Louis E. ‘The Taunt in Popular Sikh Martyrologies’. In The Transmission of Sikh Heritage in the Diaspora, ed., Pashaura Singh and N. Gerald Barrier. New Delhi: Mahohar, 1996.

———. ‘Martyrdom and Sikh Tradition’. Journal of the American Oriental Society 117, no. 4 (Oct–Dec. 1997): 623–42.

———. Martyrdom in the Sikh Tradition: Playing the ‘Game of Love.’ New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Freedberg, David. The Power of Images: Studies in the History and Theory of Response. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1989.

Hadj-Moussa, Rabita, and Michael Nijhawan. Suffering, Art and Aesthetics. New York, USA: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

McLeod, W.H. Popular Sikh Art. Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1991.

Nijhawan, Michael, and Anna C. Schultz. ‘The Diasporic Rasa of Suffering: Notes on the Aesthetics of Image and Sound in Indo-Caribbean and Sikh Popular Art.' In Suffering, Art and Aesthetics, edited by Ratiba Hadj-Moussa and Michael Nijhawan, 177-205. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

Singh, Kavita. ed., New Insights into Sikh Art. Mumbai: Marg Publication, 2003.

———. ‘Ghosts of Future Nations, or the Uses of the Holocaust Museum Paradigm in India.’ In The International Handbooks of Museum Studies: Museum Transformations, edited by Sharon Macdonald and Helen Rees Leahy. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2015.

Storm, Mary. Head and Heart: Valour and Self-Sacrifice in the Art of India. New Delhi: Routledge, 2013.

Suri, Sanjay. 1984: The Anti-Sikh Violence and After. New Delhi: HarperCollins Publishers India, 2015.

Singh Nabha, Kahn. We Are Not Hindus. Translated by Jarnail Singh. Amritsar: Singh Brothers, 2015.